Developing Empathy for Patients with Mental Illnesses Eric Tzeng and Louisa Steiger, MD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case of Steroid Induced Mania

Case Report International Journal of Psychiatry A Case of Steroid Induced Mania 1* 1 Maryam M Alnasser , Yasser M Alanzi and Amena H * 2 Corresponding author Alhemyari Maryam M Alnasse, MBBS from University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: [email protected]. 1 MBBS from University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Submitted: 14 Dec 2016; Accepted: 26 Dec 2016; Published: 30 Dec 2016 2MBBS from King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Abstract Background: Steroids have been widely used and prescribed for a variety of systemic diseases. Although they prove to be highly effective, they have many physical and psychiatric adverse effects. The systemic side effects of these medications are well known and well studied, in contrast to the psychiatric adverse effects which its phenomenology needs to be the focus of more clinical studies. However, the incidence of diagnosable psychiatric disorders due to steroid therapy is reported to be 3-6%. Affective reactions such as depression, mania, and hypomania are the most common adverse effects, along with psychosis, anxiety and delirium. Aim: We describe a case of corticosteroid induced mania, its unusual clinical picture, its course and management. Case description: A 14-year-old female intermediate school student, with a recent diagnosis of Chron’s disease was brought to A&E department due to acute behavioral disturbance in form of confusion, visual hallucinations, psychomotor agitation, irritability, hyperactivity, talkativeness, lack of sleep, and physical aggression. Those symptoms have started few days following corticosteroid therapy which was Prednisolone 40mg PO OD. And she was diagnosed with steroid induced mania. Discussion: This case illustrates the need for more understanding of the phenomenology and diversity of corticosteroids induced psychiatric syndromes. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

ICD-10 ThelCD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines | World Health Organization I Geneva I 1992 Reprinted 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. 1.Mental disorders — classification 2.Mental disorders — diagnosis ISBN 92 4 154422 8 (NLM Classification: WM 15) © World Health Organization 1992 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

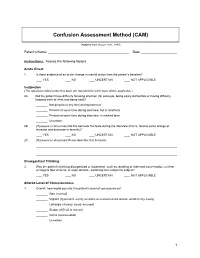

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6. -

Lamotrigine As a Treatment of Agitation in Dementia F

Lamotrigine as a treatment of agitation in Dementia F. Godinho1, A. Valverde2. 1Hospital Espirito Santo de Évora, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Évora, Portugal. 2Hospital Professor Doutor Fernando da Fonseca, Neurology Service, Amadora, Portugal. Background: • Psychomotor agitation is common in patients with dementia but there are no well-established or evidenced-based effective treatments. • Non-pharmacological interventions remain the mainstay of treatment but are not always feasible or sufficient. • Antipsychotic are the most commonly used drugs but concerns regarding tolerability limit their use. • Anticonvulsants are receiving growing attention due to their better safety profile. Objective: Methods: We report a case of a patient with dementia and behavioral disturbance Retrospective review of the clinical chart and literature review on the treated with lamotrigine, and make a brief review of the literature of topic. anticonvulsants use in the treatment of agitation and aggression in dementia. RESULTS Clinical case • A 69 years-old woman with behavioral variant Frontotemporal Dementia, severe stage, totally dependent on activities of daily living and with severe speech difficulties, developed progressive aggressive behavior. • In the following 6 months, quetiapine until 200mg/daily and then risperidone until 1mg/daily was tried, with no success. • Lamotrigine was then introduced and titrated until 100mg/daily. • Since this dosage and in the 2 next consultations, no more aggressive behavior were observed Literature Review -

Does Psychomotor Agitation in Major Depressive Episodes Indicate Bipolarity? Evidence from the Zurich Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2009) 259:55–63 DOI 10.1007/s00406-008-0834-7 ORIGINAL PAPER Jules Angst Æ Alex Gamma Æ Franco Benazzi Æ Vladeta Ajdacic Æ Wulf Ro¨ssler Does psychomotor agitation in major depressive episodes indicate bipolarity? Evidence from the Zurich Study Received: 4 September 2007 / Accepted: 5 June 2008 / Published online: 19 September 2008 j Abstract Background Kraepelin’s partial interpre- were equally associated with the indicators of bipolarity tation of agitated depression as a mixed state of and with anxiety. Longitudinally, agitation and retar- ‘‘manic-depressive insanity’’ (including the current dation were significantly associated with each other concept of bipolar disorder) has recently been the focus (OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.0–3.2), and this combined of much research. This paper tested whether, how, and group of major depressives showed stronger associa- to what extent both psychomotor symptoms, agitation tions with bipolarity, with both hypomanic/cyclothy- and retardation in depression are related to bipolarity mic and depressive temperamental traits, and with and anxiety. Method The prospective Zurich Study anxiety. Among agitated, non-retarded depressives, assessed psychiatric and somatic syndromes in a unipolar mood disorder was even twice as common as community sample of young adults (N = 591) (aged bipolar mood disorder. Conclusion Combined agitated 20 at first interview) by six interviews over 20 years and retarded major depressive states are more often (1979–1999). Psychomotor symptoms of agitation and bipolar than unipolar, but, in general, agitated retardation were assessed by professional interviewers depression (with or without retardation) is not more from age 22 to 40 (five interviews) on the basis of the frequently bipolar than retarded depression (with or observed and reported behaviour within the interview without agitation), and pure agitated depression is even section on depression. -

Identifying and Treating Postpartum Depression June Andrews Horowitz and Janice H

CLINICAL ISSUES Identifying and Treating Postpartum Depression June Andrews Horowitz and Janice H. Goodman Postpartum depression affects 10% to 20% of Despite adverse health consequences, systematic women in the United States and negatively influences PPD screening is not standard clinical practice in the maternal, infant, and family health. Assessment of risk United States. Limited availability of psychiatric factors and depression symptoms is needed to identi- services impedes referral for evaluation and treat- fy women at risk for postpartum depression for early ment. Nurses require knowledge about the nature referral and treatment. Individual and group psy- and efficacy of PPD treatments to refer their clients chotherapy have demonstrated efficacy as treatments, and recommend psychiatric services with confi- and some complementary/alternative therapies show dence. To inform nursing practice, this article promise. Treatment considerations include severity of describes PPD, examines screening approaches, and depression, whether a mother is breastfeeding, and synthesizes the literature concerning evidence-based mother’s preference. Nurses who work with childbear- treatments for PPD. ing women can advise depressed mothers regarding treatment options, make appropriate recommenda- Overview of Postpartum Depression tions, provide timely and accessible referrals, and encourage engagement in treatment. JOGNN, 34, 264–273; 2005. DOI: 10.1177/0884217505274583 Description, Prevalence, and Course Keywords: Mental health—Postpartum depres- Symptoms -

Diagnosing Bipolar Disorder in Children

Treating Children with Anxiety and Bipolar Disorder Ellen Leibenluft, M.D. Chief, Section on Bipolar Spectrum Disorders Emotion and Development Branch National Institute of Mental Health National Institutes of Health Department of Health and Human Services All research funded by NIMH Intramural Research Program Talk Outline • Diagnosing bipolar disorder in children • In DSM, BD characterized by episodes • Is BD in children characterized by non-episodic, severe irritability? • No: research comparing youth with SMD vs. those with BD • Anxiety in BD • Common comorbidity in adults and youth • Anxiety as a risk factor for BD • Anxiety in SMD • Treatment Irritability across diagnoses Dx Healthy SMD BD Anxiety At risk N 77 67 35 39 35 ANX>HV, At Risk; ANX=BD; ANX < SMD Stringaris et al, unpublished Diagnosing bipolar disorder in youth Hospital discharge diagnoses in the U.S., 1996-2004 Rate of increase in d/c’s for BD: In adults, 56% In adolescents, 400% In children, 1.3 to 7.3 per 10,000 (~600%) Blader and Carlson, 2007 Diagnosing pediatric bipolar disorder: The controversy Is severe irritability and ADHD, without distinct manic episodes, a developmental form of bipolar disorder? DSM-IV Criteria for Manic Episode: Unique features A. Distinct period of elevated, expansive, or irritable mood ≥ 1 week B. Symptoms (3, or 4 if irritable) at the same time as “A” (1) grandiosity (2) decreased need for sleep (3) pressured speech (4) flight of ideas, racing thoughts (5) distractibility (6) increased goal-directed activity, psychomotor agitation (7) excessive pleasurable activities C. Marked impairment, hospitalization, or psychosis DSM-IV Criteria for Manic Epısode: Overlap with ADHD A. -

Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Interventions for Behavior Symptoms in Dementia

Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Interventions for Behavior Symptoms in Dementia Florida State University College of Medicine Elving Colón Dementia (1 of 1) • According to DSM IV – Memory impairment and – Aphasia and/or – Apraxia and/or – Agnosia and/or – Disturbance in executive function Dementia (2 of 2) • Cognitive deficits must be – Severe enough to cause occupational and/or social impairment – Represent a decline from previous higher level of functioning Dementia Types • Alzheimer’s Dementia (55%) • Vascular Dementia (21%) • Frontotemporal Dementia (8%) • Lewy Body Dementia (5%) • Others (11%) – Infectious – Metabolic Behavior and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia (BPSD) • Umbrella term – Noncognitive symtoms and behaviors occuring in dementia – Also referred as “noncognitive symptoms of dementia“, “behavior problems”, “disruptive behaviors”, “neuropsychiatric symptoms”, “aggressive behavior”, and “agitation” – Fluctuate over time, psychomotor agitation being most persistent BPSD • Divided into 4 main subtypes – Physically aggressive behaviors • Hitting, kicking, biting – Physically nonaggressive behaviors • Pacing, inappropriately handling objects, wandering – Verbally nonaggressive agitation • Constant repetition of sentences or requests – Verbal aggression • Cursing, screaming Common BPSD in Dementia • Activity problems – Purposeless activity – Wandering – Inappropriate activities • Paranoia and delusions – Suspicion – “People are stealing my things” • Anxiety and phobias • Aggression – Verbal more than physical • Depression -

Psychopathology of Mixed States

Psychopathology of Mixed States a,b, b,c Sergio A. Barroilhet, MD, PhD *, S. Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH KEYWORDS Mixed states Psychopathology Factor structure Conceptual models Mixed depression Mixed mania KEY POINTS Mixed states are not only a mixture of depressive and manic symptoms, but reflect manic and depressive symptoms combined with the core feature of psychomotor activation. Psychomotor activation is the core feature of mixed states, independent of polarity. Dysphoria (irritability/hostility) is the next most important feature of mixed states. Kraepelin and Koukopoulos provide conceptual models that fit the empirical data regarding mixed states well and are useful clinically. INTRODUCTION Mixed states pose a problem for the concept of bipolar illness. The term, bipolar, implies that mood varies between 2 opposite poles, mania and depression. Mixed states have been seen as transitional, and uncommon, phases between depres- sion and mania.1,2 Kraepelin, who emphasized course of illness rather than polarity of mood states in the diagnosis of manic-depressive insanity (MDI), argued that most mood episodes were neither depressive nor manic, but both at the same time, ie, mixed.3 He did not emphasize polarity (depression vs mania) because he considered pure polarity (pure mania or pure depression) as infrequent, whereas mixed states were common. Influenced by Kraepelin’s opponents in the Wernicke-Kleist-Leonhard school, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of a Clı´nica Psiquia´ trica Universitaria, Facultad Medicina Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile; b Department of Psychiatry, Tufts University, School of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Pratt Building, 3rd Floor, 800 Washington Street, Box 1007, Boston, MA 02111, USA; c Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA * Corresponding author. -

Psychomotor Agitation, Anxiety Disorders, Trauma-Related Disorders

Evidence based Psychiatric Care Journal of the Italian Society of Psychiatry Original article Psychomotor agitation, anxiety disorders, Società Italiana di Psichiatria trauma-related disorders: a review of clinical manifestations in COVID-19 Patrizia Moretti, Valentina Pierotti, Francesca Brufani, Giorgio Pomili, Eleono- ra Valentini, Micaela Bozzetti, Laura Lanza, Luigi Maria Pandolfi, Giulia Men- culini, Alfonso Tortorella Department of Psychiatry, University of Perugia, Italy Summary Patrizia Moretti Introduction. The aim of our study is to highlight psychiatric clinical features due to the SARS-CoV-2 infection, providing insights from the new environmen- tal circumstances resulting from the global pandemic. Materials and Methods. We conducted a review of the most recent literature involving psychiatric consequences of COVID-19, particularly focusing on psy- chomotor agitation, anxiety disorders, trauma-related disorders and the main guidelines for the treatment of such consequences. Results. A great variety of psychiatric correlates is involved in the present pan- demic, with a relatively wide distribution. Discussion and Conclusions. We believe that promoting studies that could explore the epidemiological distribution of psychiatric and psychological dys- functional responses to the global situation may be useful. Furthermore, the possible influence that SARS-CoV-2 may exert on specific psychiatric diseas- es claims further attention. Future research with this specific focus may help a more timely and correct management of the infection, as well as the implemen- tation of actions to protect public health. How to cite this article: Moretti P, Key words: COVID-19 pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 infection, ACE2 receptor, Psy- Pierotti V, Brufani F, et al. Psychomotor chomotor agitation, Anxiety Disorders, and Trauma-Related Disorders agitation, anxiety disorders, trauma- related disorders: a review of clinical manifestations in COVID-19. -

The Pathologization, Psychologization, and Privatization

1 BOTTLED TEARS: THE PATHOLOGIZATION, PSYCHOLOGIZATION, AND PRIVATIZATION OF GRIEF LEEAT GRANEK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PSYCHOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, ONTARIO OCTOBER 2008 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90378-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90378-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.