Identifying and Treating Postpartum Depression June Andrews Horowitz and Janice H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effectiveness of Music Therapy for Postpartum Depression A

Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 37 (2019) 93–101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ctcp The effectiveness of music therapy for postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis T Wen-jiao Yanga, Yong-mei Baib, Lan Qinc, Xin-lan Xuc, Kai-fang Baoa, Jun-ling Xiaoa, ∗ Guo-wu Dinga, a School of Public Health, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China b School of Public Health, Capital Medical University, Beijing, 10069, China c School of Mathematics and Statistics, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China 1. Introduction rehabilitative approaches, relational approaches, and music listening, among which, music listening is the most convenient to conduct [18]. Postpartum depression usually refers to depression that occurs A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2009 found that within one year after giving birth [1]. According to some current re- music therapy based on standard care reduced depression and anxiety search reports, the prevalence of postpartum depression is higher than in people with mental disorders [19]. Another meta-analysis also re- 10% and lower than 20% but can be as high as 30% in some regions vealed a positive effect of music therapy on the alleviation of depression [1–3]. Postpartum depression symptoms include emotional instability, and anxiety symptoms [20]. However, the efficacy of music therapy sleep disorders, poor appetite, weight loss, apathy, cognitive impair- cannot be generalized to patients with other diseases because women ment, and in severe cases, suicidal ideation [4,5]. Postpartum depres- with postpartum depression are a special group whose main symptom is sion threatens the health of the mother, as well as the physical and depression. -

Postpartum Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PPTSD ) ~ an Anxiety Disorder 14

POSTPARTUM PTSD: PREVENTION AND TREATMENT Project ECHO 2017 Amy-Rose White MSW, LCSW 2 Perinatal Psychotherapist ~ Salt Lake City (541) 337-4960 www.arwslctherapist.com Utah Maternal Mental Health Collaborative Founder, Director & Board Chair www.utahmmhc.org [email protected] Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Utah Maternal Mental Health Collaborative 3 www.utahmmhc.com Resources: Support Groups Providers Sx and Tx brochure/handouts Training Meets Bi-monthly on second Friday of the month. Email Amy-Rose White LCSW- [email protected] Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Session Objectives 4 Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Defining the issue: 5 What is Reproductive Trauma? Perinatal Mood, Anxiety, Obsessive Compulsive & Trauma Related disorders Postpartum PTSD- An anxiety disorder Why is it relevant to birth professionals? Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 6 Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Reproductive Trauma in context 7 Reproductive trauma refers to any experience perceived as a threat to physical, psychological, emotional, or spiritual integrity related to reproductive health events. This includes the experience of suffering from a perinatal mood or anxiety disorder. The experience of maternal mental health complications is itself often a traumatic event for the woman and her entire family. Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Common Reproductive Traumas 8 Unplanned pregnancy Infertility Pregnancy Abortion complications Miscarriage Difficult, prolonged, or Stillbirth painful labor Maternal complications Short intense labor during/following Fetal medical delivery complications NICU stay Amy-Rose White LCSW 2016 Trauma Informed Birth Practices 9 www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma‐intervent Consider: ions ~ Trauma informed care federal guidelines PAST ACE Study ~ Adverse Childhood Events Study > Development of health and PRESENT mental health disorders http://www.acestudy.org FUTURE Research on early stress and trauma now indicates a direct relationship between personal history, breakdown of the immune system, and the formation of hyper- and hypo-cortisolism and inflammation. -

A Case of Steroid Induced Mania

Case Report International Journal of Psychiatry A Case of Steroid Induced Mania 1* 1 Maryam M Alnasser , Yasser M Alanzi and Amena H * 2 Corresponding author Alhemyari Maryam M Alnasse, MBBS from University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: [email protected]. 1 MBBS from University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Submitted: 14 Dec 2016; Accepted: 26 Dec 2016; Published: 30 Dec 2016 2MBBS from King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Abstract Background: Steroids have been widely used and prescribed for a variety of systemic diseases. Although they prove to be highly effective, they have many physical and psychiatric adverse effects. The systemic side effects of these medications are well known and well studied, in contrast to the psychiatric adverse effects which its phenomenology needs to be the focus of more clinical studies. However, the incidence of diagnosable psychiatric disorders due to steroid therapy is reported to be 3-6%. Affective reactions such as depression, mania, and hypomania are the most common adverse effects, along with psychosis, anxiety and delirium. Aim: We describe a case of corticosteroid induced mania, its unusual clinical picture, its course and management. Case description: A 14-year-old female intermediate school student, with a recent diagnosis of Chron’s disease was brought to A&E department due to acute behavioral disturbance in form of confusion, visual hallucinations, psychomotor agitation, irritability, hyperactivity, talkativeness, lack of sleep, and physical aggression. Those symptoms have started few days following corticosteroid therapy which was Prednisolone 40mg PO OD. And she was diagnosed with steroid induced mania. Discussion: This case illustrates the need for more understanding of the phenomenology and diversity of corticosteroids induced psychiatric syndromes. -

Perinatal Depression Policy Brief Authors

PERINATAL DEPRESSION POLICY BRIEF AUTHORS . ANDREA GRIMBERGEN, BA . ANJALI RAGHURAM, BA . JULIE M. DORLAND, BS, BA . CHRISTOPHER C. MILLER, BMus . NANCY CORREA, MPH . CLAIRE BOCCHINI, MD, MS DEVELOPMENT OF AN EVIDENCE-BASED PERINATAL DEPRESSION STRATEGY About the Center for Child Health Policy and Advocacy The Center for Child Health Policy and Advocacy at Texas Children’s Hospital, a collaboration between the Baylor College of Medicine Department of Pediatrics and Texas Children’s Hospital, delivers an innovative, multi-disciplinary, and solutions-oriented approach to child health in a vastly evolving health care system and market place. The Center for Child Health Policy and Advocacy is focused on serving as a catalyst to impact legislative and regulatory action on behalf of vulnerable children at local, state, and national levels. This policy brief is written to address the needs of mothers impacted by perinatal depression as their health impacts the well-being of their children. Contributors Andrea Grimbergen, BA Anjali Raghuram, BA Julie M. Dorland, BS, BA Christopher C. Miller, BMus Nancy Correa, MPH Claire Bocchini, MD, MS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Perinatal depression (PPD) is a serious depressive mood disorder that affects mothers during pregnancy and the year following childbirth. While there is no formal collection of PPD diagnoses across the U.S., it is estimated that 10-25% of women suffer from PPD. Although PPD is a treatable mental illness, it is under-diagnosed and undertreated. This is especially troubling due to the documented adverse effects of maternal depression on child health and development. Many documented barriers exist to successful PPD treatment including: stigma, lack of community and patient education, disconnect between available and preferred treatment options, lack of familial and provider support, poor healthcare accessibility in rural communities, and logistical barriers at the provider and patient levels. -

Early Identification and Treatment of Pregnancy-Related Mental Health Problems

Early identification and treatment of pregnancy-related mental health problems Talking about depression Obstetric patients are encouraged to discuss mental health issues with their providers, says Rashmi Rao, MD, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist. “I tell patients I consider mental health problems as important as any other disorder,” Dr. Rao says. “We don’t feel bashful talking about hypertension or diabetes. I don’t want them to feel like there is a stigma around talking about mood disorders.” UCLA has identified numerous opportunities for providers to recognize the risk factors and symptoms of pregnancy-related mood disorders. Early treatment The understanding of perinatal mental health disorders such as postpartum can mitigate the effects of the depression (PPD) has evolved considerably over the last several decades. The disorder on women and their American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has provided families, says obstetrician guidance on screening, diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in pregnancy Aparna Sridhar, MD, MPH. and postpartum. UCLA has implemented a range of services to adhere to the ACOG “There is significant impact guidelines and minimize the impact of these disorders on patients and their families. of untreated mental health disorders on the health of Improved knowledge about a common condition mothers and babies. Studies Postpartum depression affects as many as 10-to-20 percent of new mothers and suggest that postpartum depression can impact how can occur any time during the first year following childbirth, although most cases infants grow, breastfeed and arise within the first five months. The condition can range in severity from mild sleep,” she says. -

Phenomenology, Epidemiology and Aetiology of Postpartum Psychosis: a Review

brain sciences Review Phenomenology, Epidemiology and Aetiology of Postpartum Psychosis: A Review Amy Perry 1,*, Katherine Gordon-Smith 1, Lisa Jones 1 and Ian Jones 2 1 Psychological Medicine, University of Worcester, Worcester WR2 6AJ, UK; [email protected] (K.G.-S.); [email protected] (L.J.) 2 National Centre for Mental Health, MRC Centre for Neuropsychiatric Genetics and Genomics, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF24 4HQ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Postpartum psychoses are a severe form of postnatal mood disorders, affecting 1–2 in every 1000 deliveries. These episodes typically present as acute mania or depression with psychosis within the first few weeks of childbirth, which, as life-threatening psychiatric emergencies, can have a significant adverse impact on the mother, baby and wider family. The nosological status of postpartum psychosis remains contentious; however, evidence indicates most episodes to be manifestations of bipolar disorder and a vulnerability to a puerperal trigger. While childbirth appears to be a potent trigger of severe mood disorders, the precise mechanisms by which postpartum psychosis occurs are poorly understood. This review examines the current evidence with respect to potential aetiology and childbirth-related triggers of postpartum psychosis. Findings to date have implicated neurobiological factors, such as hormones, immunological dysregulation, circadian rhythm disruption and genetics, to be important in the pathogenesis of this disorder. Prediction models, informed by prospective cohort studies of high-risk women, are required to identify those at greatest risk of postpartum psychosis. Keywords: postpartum psychosis; aetiology; triggers Citation: Perry, A.; Gordon-Smith, K.; Jones, L.; Jones, I. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders : Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines

ICD-10 ThelCD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines | World Health Organization I Geneva I 1992 Reprinted 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004 WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders : clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. 1.Mental disorders — classification 2.Mental disorders — diagnosis ISBN 92 4 154422 8 (NLM Classification: WM 15) © World Health Organization 1992 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers' products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

Psychiatric Disorders in the Postpartum Period

BCMJ /#47Vol2.wrap3 2/18/05 3:52 PM Page 100 Deirdre Ryan, MB, BCh, BAO, FRCPC, Xanthoula Kostaras, BSc Psychiatric disorders in the postpartum period Postpartum mood disorders and psychoses must be identified to prevent negative long-term consequences for both mothers and infants. ABSTRACT: Pregnant women and he three psychiatric disor- proportion of women with postpartum their families expect the postpartum ders most common after the blues may develop postpartum de- period to be a happy time, charac- birth of a baby are postpar- pression.3 terized by the joyful arrival of a new Ttum blues, postpartum de- baby. Unfortunately, women in the pression, and postpartum psychosis. Postpartum depression postpartum period can be vulnera- Depression and psychosis present The Diagnostic and Statistical Man- ble to psychiatric disorders such as risks to both the mother and her infant, ual of Mental Disorders, Fourth postpartum blues, depression, and making early diagnosis and treatment Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) psychosis. Because untreated post- important. (A full description of phar- defines postpartum depression (PPD) partum psychiatric disorders can macological and nonpharmacological as depression that occurs within have long-term and serious conse- therapies for these disorders will 4 weeks of childbirth.4 However, most quences for both the mother and appear in Part 2 of this theme issue in reports on PPD suggest that it can her infant, screening for these dis- April 2005.) develop at any point during the first orders must be considered part of year postpartum, with a peak of inci- standard postpartum care. Postpartum blues dence within the first 4 months post- Postpartum blues refers to a transient partum.1 The prevalence of depression condition characterized by irritability, during the postpartum period has been anxiety, decreased concentration, in- systematically assessed; controlled somnia, tearfulness, and mild, often studies show that between 10% and rapid, mood swings from elation to 28% of women experience a major sadness. -

Postpartum Depression & Anxiety

Provincial Reproductive Mental Health www.bcwomens.ca patient guide Self-care Program for Women with Postpartum Depression and Anxiety Created and edited by Doris Bodnar, MSN, Deirdre Ryan, MB, FRCPC Jules E. Smith, MA, RCC 2 PROVINCIAL REPRODUCTIVE MENTAL HEALTH WWW.BCWOMENS.CA “Make Positive Changes” introduction THIS MANUAL WAS CREATED to meet the need of both women with postpartum depression and the health care providers who treat these women and their families. Our goals were to: 1. educate about the causes, presentation and different treatments of postpartum depression 2. provide structured exercises to help women become active participants in their own treatment and recovery. What is the Provincial Reproductive Mental Health Program? We are a group of practitioners and researchers based at the Provincial Reproductive Mental Health Program at BC Children and Women’s Health Centre and St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, BC. We represent several disciplines including psychiatry, psychology, nursing and nutrition. Together, we have many years of clinical experience working with women and their families dealing with emotional difficulties related to the reproductive cycle. We bring a wide range of skills and life experiences to the preparation of this manual as well as the experience of other women who have been treated and recovered from postpartum depression. Who Is This Manual For? For Women: This manual is targeted for women who are having emotional difficulties in the postpartum period. We hope it will guide you to make positive changes in your postpartum experience. This information alone, however, will not be enough to treat your illness. You must also speak to your doctor, public health nurse, mental health worker or other health care provider about appropriate treatment options. -

The Epidemiology of Mental Health Issues in the Caribbean

THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES IN THE CARIBBEAN Dr. Nelleen Baboolal M.B.B.S., Dip. Psych., D.M. Psych. Senior Lecturer in Psychiatry The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Campus Caribbean region ¨ Consists of 26 countries and territories ¨ Most countries classified as Small Island Developing States (SIDS) by the United Nations ¨ Haiti one of the least developed countries in the world Caribbean ¨ Antigua and Barbuda ¨ Bahamas ¨ Cuba ¨ Grenada ¨ Guyana ¨ Haiti ¨ Jamaica ¨ St. Lucia ¨ Dominica ¨ Martinique ¨ Guadelope ¨ Dominica ¨ Monsterrat ¨ Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao ¨ Puerto Rico ¨ Santo Domingo ¨ British and United States Virgin Islands 21st Century Caribbean ¨ British West Indies ¨ Spanish Caribbean (now regarded as part of Latin America) ¨ French Caribbean (still politically part of mainland France) ¨ Dutch Antilles ¨ Fragments still owned by the United States (Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands) Migration patterns ¨ European settlers moving to the West Indies ¨ Africans slaves to work on plantations ¨ After abolition of slavery indentured labour from India and China ¨ Secondary immigration of Caribbean people to Central America, North America, UK to seek employment Hickling . Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan Am J Public Health 18(4/5), 2005 257 Caribbean and disasters ¨ Caribbean particularly vulnerable to both natural and human generated disasters ¨ Disasters include floods, earthquakes, volcanoes, droughts. Mass death due to illness, violence ¨ 1970 to 2000 the Caribbean region recorded average 32.4 disasters per year -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

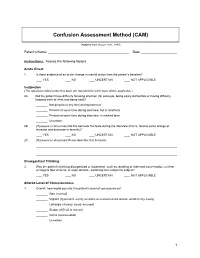

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6.