1970 Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Lempriere Mid-20Th Century Representations of Aboriginal Themes Gloria Gamboz

Helen Lempriere Mid-20th century representations of Aboriginal themes Gloria Gamboz The best-known legacy of the While living in Paris and London in half of the 20th century has created Australian painter, sculptor and the 1950s, Lempriere was influenced some contention, and these works are printmaker Helen Lempriere by anthropological descriptions of now being reinvestigated as part of (1907–1991) is the sculpture prize Australian Indigenous cultures, and a broader examination of emerging and travelling scholarship awarded in developed a highly personal and Australian nationhood. A study of her name. Less well known, however, expressive mode of interpretation Lempriere’s life, influences and key are her post–World War II works that blended Aboriginal themes with works provides an insight into the exploring Aboriginal myths, legends her own vision. The appropriation cultural climate of post–World War II and iconography. Twelve of these of Aboriginal themes by non- Australia, and the understanding of are held by the Grainger Museum Indigenous Australian women Aboriginal culture by non-Indigenous at the University of Melbourne, and artists like Lempriere in the first women artists. have recently been made available on the museum’s online catalogue.1 They form part of a wider collection of works both by, and depicting, Helen Lempriere, bequeathed by Lempriere’s husband, Keith Wood, in 1996.2 The collection is likely to have come to the Grainger Museum through a mutual contact, the Sydney- based curator, collector and gallery director Elinor -

The Secret History of Australia's Nuclear Ambitions

Jim Walsh SURPRISE DOWN UNDER: THE SECRET HISTORY OF AUSTRALIAS NUCLEAR AMBITIONS by Jim Walsh Jim Walsh is a visiting scholar at the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He is also a Ph.D. candidate in the Political Science program at MIT, where he is completing a dissertation analyzing comparative nuclear decisionmaking in Australia, the Middle East, and Europe. ustralia is widely considered tactical nuclear weapons. In 1961, of state behavior and the kinds of Ato be a world leader in ef- Australia proposed a secret agree- policies that are most likely to retard forts to halt and reverse the ment for the transfer of British the spread of nuclear weapons? 1 spread of nuclear weapons. The nuclear weapons, and, throughout This article attempts to answer Australian government created the the 1960s, Australia took actions in- some of these questions by examin- Canberra Commission, which called tended to keep its nuclear options ing two phases in Australian nuclear for the progressive abolition of open. It was not until 1973, when history: 1) the attempted procure- nuclear weapons. It led the fight at Australia ratified the NPT, that the ment phase (1956-1963); and 2) the the U.N. General Assembly to save country finally renounced the acqui- indigenous capability phase (1964- the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty sition of nuclear weapons. 1972). The historical reconstruction (CTBT), and the year before, played Over the course of four decades, of these events is made possible, in a major role in efforts to extend the Australia has gone from a country part, by newly released materials Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of that once sought nuclear weapons to from the Australian National Archive Nuclear Weapons (NPT) indefi- one that now supports their abolition. -

The Encyclical Dissected by Morag Fraser, William Uren (P6), William Daniel (P8), 36 Andrew Hamilton (P9), Ray Cassin (Plo), ALTERNATIVE WORLDS and John Ryan (Pl2)

to war Michael McKernan Maslyn Williams Morag Fraser Peter Steele Volume 3 Number 9 EURI:-KA srm:-s November 1993 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theology CoNTENTS 4 28 COMMENT PASSAGES OF ARMS Chris McGillion on the church and politi Peter Steele ponders war and the way in calleadership. which writers have rendered it. 5 35 VERIT ATIS SPLENDOR QUIXOTE The encyclical dissected by Morag Fraser, William Uren (p6), William Daniel (p8), 36 Andrew Hamilton (p9), Ray Cassin (plO), ALTERNATIVE WORLDS and John Ryan (pl2). Max Teichmann examines promises and reality in international politics. 13 CAPITAL LETTER 39 IN MEMORIAM 14 Andrew Bullen recalls the life and poetry of LETTERS Francis Webb. 16 44 A DOG'S BREAKFAST BOOKS AND ARTS Mark Skulley unravels the politics of Ross McMullin reviews Michael Cathcart's pay TV. abridgement of Manning Clark's A History of Australia; Margaret Simons visits writ 19 ers' week at Brisbane's Warana Festival ARCHIMEDES (p45), and the Asia-Pacific Triennial at the Queensland Art Gallery (pSO); Geoffrey 20 Milne surveys theatre in the Melbourne REPORTS International Festival (p46); Damien Col Dave Lane on newsagents in Canberra; eridge considers myths, marketing and the Frank Brennan on the Mabo outcome (p21 ); forthcoming Van Gogh exhibition at the Jon Greenaway on moves for a constitution National Gallery of Victoria (p48). al convention (p25). 51 22 FLASH IN THE PAN WHAT AUSTRALIANS REMEMBER Reviews of the films In the Line of Fire, The Cover: Australian soldier Michael McKernan reflects on the' Austral Nostradamus Kid, Blackfellas, So I Married on the western front. -

Engaging Southeast Asia? Labor's Regional

BenvenutiAustralia’s Miandlitary Martin Wit Joneshdrawal from Singapore and Malaysia Engaging Southeast Asia? Labor’s Regional Mythology and Australia’s Military Withdrawal from Singapore and Malaysia, 1972–1973 ✣ Andrea Benvenuti and David Martin Jones Introduction The decision in 1973 to withdraw Australian forces from Malaysia and Singa- pore constitutes a neglected but deªning episode in the evolution of Austra- lian postwar diplomacy against the backdrop of the Cold War.1 A detailed ex- amination of this episode sheds interesting light on Australian foreign policy from 1972 to 1975, the years when Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) served as prime minister. The Whitlam government’s policy in Southeast Asia was not as much of a watershed as the secondary literature suggests. The dominant political and academic orthodoxy, which developed when the ALP was in power from 1983 to 1996 and has subsequently retained its grip on Australian academe, holds that the Whitlam government transformed Australian foreign policy and established the basis for Australia’s successful en- gagement with the Asian region. Proponents of this view claim that Whitlam ended his Liberal predecessors’ uncritical support for U.S. and British Cold War policies in Southeast Asia and turned Australia into a more credible, reli- able, and valuable regional partner.2 The foreign policy editor of The Austra- 1. Little has been written on the Whitlam government’s approach to the Five Power Defence Arrange- ments. See Henry Albinski, Australian External Policy under Labor: Content, Process and the National Debate (Brisbane: University of Queensland, 1977), pp. 241–245; John Ingleson, “South-East Asia,” in W. -

The Past and Other Countries

Vol. 4 No. 2 March 1994 $5.00 The past and other countries South Africa looks forward to democracy: Tammy Mbengo and Maryanne Sweeney Western Australia looks back to separate development: Mark Skulley Stephen Gaukroger and Keith Campbell chase John Carroll through the ruins of Western civilisation Paul Barry chases Conrad Black through the corridors of power Deborah Zion juggles Jewish tradition and the ordination of women rabbis Elaine Lindsay flies to the moon with a post-Christian feminist Ray Cassin watches moral theology try to stay down to earth H.A.Willis is in pain, and asks when it will end In 1993, Eureka Street photographer Emmanuel Santos went to Europe to visit the Nazi death camps. His cover photograph shows David Dann in Majdanek, confronting a past that destroyed his family. On this page Santos catches part of Europe's present: Catholic youth in Warsaw preparing for an anti-Semitic demonstration during the commemoration of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. The young men claim that Poland should be for the Poles: no Jews, no Russians, no Germans, no immigrants. Volume 4 Number 2 EURI:-KA SJRI:-Er March 1994 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theology CoNTENTS 4 28 COMMENT ONTHERACK H. A Willis explores the world of 6 the chronic pain sufferer. LETTERS 33 8 QUIXOTE CAPITAL LETTER 34 10 BOOKS STRIFE ON THE WESTERN FRONT Stephen Gaukroger and Keith Campbell Mark Skulley reports on the lingering sen take issue with John Carroll's Humanism: timent for secession in Western Australia. The Wrecl{ of Western Culture; Paul Barry sums up Conrad Black's A Life In Progress 14 (p38); Max Teichmann reviews Gore Vidal's SOLDIER'S STORY United States Essays 1952- 1992 (p40). -

An Inquiry Into Contemporary Australian Extreme Right

THE OTHER RADICALISM: AN INQUIRY INTO CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN EXTREME RIGHT IDEOLOGY, POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION 1975-1995 JAMES SALEAM A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Of Philosophy Department Of Government And Public Administration University of Sydney Australia December 1999 INTRODUCTION Nothing, except being understood by intelligent people, gives greater pleasure, than being misunderstood by blunderheads. Georges Sorel. _______________________ This Thesis was conceived under singular circumstances. The author was in custody, convicted of offences arising from a 1989 shotgun attack upon the home of Eddie Funde, Representative to Australia of the African National Congress. On October 6 1994, I appeared for Sentence on another charge in the District Court at Parramatta. I had been convicted of participation in an unsuccessful attempt to damage a vehicle belonging to a neo-nazi informer. My Thesis -proposal was tendered as evidence of my prospects for rehabilitation and I was cross-examined about that document. The Judge (whose Sentence was inconsequential) said: … Mr Saleam said in evidence that his doctorate [sic] of philosophy will engage his attention for the foreseeable future; that he has no intention of using these exertions to incite violence.1 I pondered how it was possible to use a Thesis to incite violence. This exercise in courtroom dialectics suggested that my thoughts, a product of my experiences in right-wing politics, were considered acts of subversion. I concluded that the Extreme Right was ‘The Other Radicalism’, understood by State agents as odorous as yesteryear’s Communist Party. My interest in Extreme Right politics derived from a quarter-century involvement therein, at different levels of participation. -

Remembering the Battle for Australia

Remembering the Battle for Australia Elizabeth Rechniewski, University of Sydney Introduction On 26 June 2008 the Australian minister for Veterans’ Affairs, Alan Griffin, announced that ‘Battle for Australia Day’ would be commemorated on the first Wednesday in September; this proclamation fulfilled a Labor Party election promise and followed a ten-year campaign by returned soldiers and others to commemorate the battles that constituted the Pacific War. The very recent inauguration of this day enables an examination of the dynamics of the processes involved in the construction of national commemorations. The aim of this article is to identify the various agencies involved in the process of ‘remembering the Battle for Australia’ and the channels they have used to spread their message; to trace the political and historical controversies surrounding the notion of a ‘Battle for Australia’ and the conflicting narratives to which they have given rise; and to outline the ‘chronopolitics,’ the shifts in domestic and international politics that ‘over time created the conditions for changes in the memoryscape and, sometimes, alterations in the heroic narrative as well’ (Gluck 2007: 61). The title of this article is intended to recall Jay Winter’s insistence that the terms ‘remembering’ and ‘remembrance’ be used, rather than memory, in order to emphasise the active role of agents in the creation and perpetuation of memory and acts of commemoration (2006: 3). Timothy Ashplant, Grant Dawson and Michael Roper, in a broad ranging study of war memory, emphasise the role of constituencies, or agents of remembrance in the process of memory formation and the struggle to articulate distinct and often competing memories in the array of arenas available. -

Strategic Studies in a Changing World T.B

2 Strategic Studies in a Changing World T.B. Millar This essay was previously published in the 40th anniversary edition. It is reprinted here in its near original format. At the beginning of his excellent book of memoirs, Dean Acheson quotes the 13th-century Spanish monarch Alphonso X, who said that if he had been present at the creation of the universe, he would have had some sound advice to give the Creator for a rather better ordering of things. Having been present at the creation of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre (SDSC), I cannot absolve myself of any responsibility, but looking at its achievements over these 25 years (1966–91), I can only wonder at the size and strength of the oak that has sprung from the acorn we then planted. I joined The Australian National University (ANU) when I was in London in July 1962, and arrived in Canberra by train in October. Canberra railway station in those days was, I believe, the original edifice, built out of weatherboards 50 years earlier and painted government brown. It was an appropriate station for a one-horse country town; it was not particularly appropriate for the national capital, but the national capital was only in the early stages of moving from the one-horse country town it had been to becoming the city we now have. The lake bed had been scraped, and the lake was beginning 17 A NatiONAL ASSeT to fill. Those crude barrack-like structures that were to house so much of the Department of Defence had not yet been built. -

Civilian Militarists

John CIVILIAN Playford MILITARISTS The author discusses the expansion of strategic studies in Australian universities, the cold war concepts on which the studies are based and the dangers inherent in these develop ments. Our problem lias been that wc expect the voice ot tenoi to be fren/ied. and that ol madness irrational. It is quite the contrary in a world where genial, m iddleaged C»eneral> consult with precise social scientists about the parameters of the death equation, and the problem ol its maximization.1 IX AMERICA, the 11011-military advisers to the Delense Depart ment, such as Herman Kahn, Thomas C. Schelling. Henry A. Kissinger and Albert Wohlstetter,. have been aptly termed crack pot realists" by C. Wright Mills and ‘T he New Civilian Militar ists-' by Irving Louis Horowitz. Although not officially connected to any branch of the armed services, they have assumed the pre dominant influence in many areas ol strategic policy. 1 hey have completely overwhelmed the military profession, in both quali tative and quantitative terms, in their contribution to the litera ture of strategic studies. They increasingly dominate the field of education and instruction in the subject. Indeed, with the exception of restricted fields ot professional knowledge, the aca demic and quasi-academic centres of strategic studies have displaced the staff colleges and war colleges. Despite the grumbles of the generals, the civilian militarists have created a more flexible and more potent war machine than anything that could have been imagined by the old service-club approach of the career men in the armed services. -

Monash Plans· Seaside Camp

JoInt "entwe rtf. YMeA: MONASH PLANS· SEASIDE CAMP MONASH Uninrsity il planning to denlop ito own year-round camp at Shorehom on the Morn ington Peninlulo, 46 milel from the compul. The property covers about 26 acres at Shoreham and is situated about 400 yards from a sheltered beach and 900 yards from Point Leo Surf Beach. The camp is owned by the V.M.C.A. of Melbourne and baa been temporarily closed this year. Subject to the fmalising of present negotiations the camp will be rc·opcncd and named the W. fL Buxton Education and Recreational Centre: after the man who originally donated the property to the V.M.C.A. Il is planned to open the camp on February 1 next year and it is hoped it. first usc will be a university "Freshen' Camp" for first-year intake students. The camp wiD be avoilable for uae by My member or sroup of Moaaah and the V.M.C.A. Outside orpniaatioDS may aIoo hire the camp and it is anticipated many schoob than that of the normal institutional accommodation for 72 people. There nCI.AllaN hall a' the ump MONth will do so. envirollJllCnt. U is one donnitory for 24 people and P'OPO'" 10 develop in ptrtnenhip Bookings may be made through In conjunction with Mr. Davies of with the YMCA. a.:ow left i$ a view six huts each taking eight people. of one of the ne.,by bee.che •. the Sports and Recreations the V.M.C.A. a proposal was ODe hundred persons can also be Association, ext. -

Isotopes and Identity: Australia and the Nuclear Weapons Option, 1949-1999

JACQUES E.C. HYMANS Isotopes and Identity: Australia and the Nuclear Weapons Option, 1949-1999 JACQUES E.C. HYMANS1 Jacques E.C. Hymans is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Government at Harvard University. In his dissertation, he is analyzing the nuclear policies of a diverse set of middle powers from around the globe. He has presented his work at academic fora in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States. ne of the most impressive historical transfor- As Jim Walsh underscored in his pathbreaking 1997 mations in state nuclear weapons policies has article on Australia in The Nonproliferation Review, if Obeen Australia’s switch from active supporter analysts in academic and policy circles have long over- of the development and spread of the bomb in the 1950s looked the Australian case it is because of their over- and 1960s, to world leader in the effort to rein it in from reliance on a model that assumes states make rational the 1970s to the present day. There is a wide gap, to say responses to objective threats.3 But from such a perspec- the least, between 1950s-era Australia’s hospitable wel- tive, it is hard to see why Australia, a country blessed come to British nuclear tests on its mainland, and its with a supremely “lucky” geographical position, was so later angry condemnations of French tests thousands of eager to participate in Western nuclear defenses— miles from its shores. Moreover, from today’s vantage thereby raising its significance as a Chinese or Soviet point it seems almost inconceivable that successive Aus- nuclear target. -

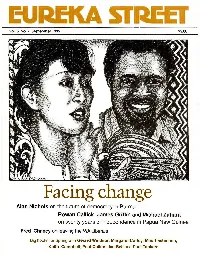

Facing Change

Vol. 5 No. 7 September 1995 $5.00 Facing change Alan Nichols on the future of democracy in Burma Rowan Callick, James Griffin and Michael Zahara on twenty years of independence in Papua New Guinea Fred Chaney on leaving the WA Liberals Big books for Spring with Gerard Windsor, Margaret Coffey, Max Teichmann, Keith Campbell, Paul Coltins, lan Bell and Paul Tankard The Change In younger, idler days he used to wonder What had become of all that he had learned. Sane as the next man, he'd been prompt to forget Most of it out of hand. To polish and marshal Minutiae, like an idiot savant, Was never his gift, his calling. The craquelure Close to the door-jamb, the mirror-flash as a meat-van Hugged a roundabout, the solitaire Au bade of a sparrow trying out the day- They were dismissed to the nothing from which they came. It was the same with those other invaders, the books. Turning the pages as if unleaving a forest, He gave them away, apart from oddments and offcuts: The nickname of Albert the Great, Hobbes with his picture Of laughter as martial, Cleopatra calling for billiards. As he got older, his question displayed the answer Knotted within it: all that he'd ever learned, Favoured or exiled, was turning into fear- Not of the kind that insight can bring to heel, But the shear of the ice-wall meeting the unplumbed ocean. Peter Steele 2 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1995 Volume 5 Number 7 September 1995 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theology CoNTENTS 2 29 POETRY THE DEVIL'S ERA Th e Change, by Peter Steele.