MARYBOROUGH) 1850-1980 Historic Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pyrenees Shire Town and Rural District Names and Boundaries

PYRENEES SHIRE TOWN AND RURAL DISTRICT NAMES AND BOUNDARIES NORTHERN GRAMPIANS M A A NAVARRE R R Y A B R S T O A A R T W BARKLY O E L U L REDBANK G H S U N R ST WAT A A TLE Y R S NA CR EEK IA NATTE UD D YALLOCK R L A A V S F O T C N L r R A MOONAMBE A e T v R E i N D R RD S A N RATHSCAR R U S D C E D B H D M O W O O A W LANDSB A O N R ROU R N B GH I S TA L O A A WE E S H T B U C S G S WAREEK a U c H H o v A T B H E SHAY W A S A Y WARRENMANG C R M O FLA V T A O H AVOCA PERCYDALE CENTRAL PY RE NE ES S HW GOLDFIELDS E Y U R N D R R BUNG BONG OWLANDS K A CR k E Y Y W e S e E r H H I GLENLOFTY A C E W R O C K L N IC TR A PA EN M GL E ra P e V m L im O et E W B U R G LICUR S LIL H t ELMHURST e L B E PY Y REN EES AMPHITHEATRE RD R iv e r BURNBANK GLENLOGIE T O LB A LEXTON T ON MOUNT LONARCH XT LE EVANSFORD D R CHUTE HEPBURN H BU W ANGOR N Y O T X E RAGLAN L GLENBRAE WAUBRA WATERLOO I L G A W N ARARAT MIDDLE ES K T ER A N L Horse K MAIN L CREE A Lagoon LEAD K B T R LEGEND U FO U ERCILDOUNE A A BE N CHUTE TOWN AND RURAL G DISTRICT BOUNDARIES O R BEAUFORT (defined as localities in Govt. -

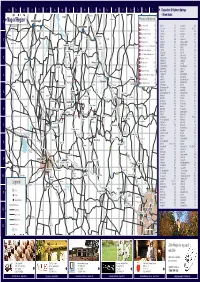

Map of Region

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T Daylesford & Hepburn Springs r t - Street Index Maldon Harc ou A 300 Redesdale Places of Interest Map of Region Mar ybor ough Cairn C 282 1 Curran Pyrenees Hwy Homebush Reservoir Castlemaine 6 Anderson’s Mill G6 First St F8 Hospital St H12 7 Blackwood Spring L8 Second St F7 Houston St H15, J15 Carisbr Craigieook Welshmans Third St F7 Howe St H13 Reef 8 Daylesford Cemetary J6 Fourth St F7 Ingrow Ln G10 Avoca B 180 Chewt on tElphins one Fifth St E7 Isset St I 18 B 180 Metcalfe 9 Firth Park M7 2 B 180 Pyalong Sixth St E6 Jamieson St H11 A 300 10 Hanging Rock P6 Seventh St E6 Jubilee Lake Rd H18 Bung Bong Tullaroop Green Eighth St E5 Kidds Gully Rd H9 New st ead 11 Kingston Avenue of Honour G6 Reservoir Gully Ninth St E5 Strathlea Yapeen King St G15 Fryerstown Taradale Tenth St E5 Knox St J12 C 287 Strangways Vaughn 12 Leitches Creek Spring K6 Eleventh St E4 Lake Rd H17 Lost Children’s Monument J6 Guildf or d 13 Twelfth St D4 Lakeside Dr E5 Sandon C 794 C C 326 3 a Fourteenth St D4 l 14 Lyonville Spring K6 Langdon Crt E12 Talbot d e y Fifteenth St D4 Leggatt St F16 C 283 r w F Clydesdale Malmsbur y w 15 Mt Beckworth D5 H Sixteenth St C3 Little St H11 y d n 16 Mt Franklin J4 Seventeenth St C3 Lone Pine Ave F3 Ctampbell own a l d Eighteenth St C3 Caralulup Yandoit i Lyman St K17 Dunach M 17 Newlyn Reservoir H7 Nineteenth St C2 Main Rd C2 Drummond 4 Burnbank 18 Sailors Falls Mineral Spring I6 Twentieth St C2 Malmsbury Rd J12 C 287 Franklinford Lauriston Cobaw Ajax Rd C5 Macadam St G16 C 316 19 Trentham -

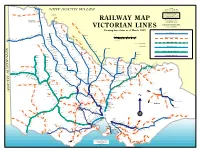

Railway Map Victorian Lines

Yelta Merbein West NOTES Mildura NEW SOUTH WALES All stations are shown with MerbeinIrymple their most recent known names. Redcliffs Abbreviations used Robinvale to Koorakee Morkalla Werrimull Karawinna Yatpool built by VR construction Meringurarrara BG = Broad Gauge (5' 3") Y Pirlta Thurla branch but never handed Benetook over to VR for traffic. Karween Merrinee SG = Standard Gauge (4' 8 1/2") Bambill Carwarp NG = Narrow Gauge (2' 6") Koorakee Boonoonar Benanee RAILWAY MAP Nowingi towards Millewa South Euston All lines shown are or were built by VR construction branch never handed over to VR for traffic, Nowingi Broad Gauge (5' 3") ownership sold to Brunswick Robinvale Plaster Mills 1942 unless otherwise shown. Balranald Bannerton Yangalake No attempt has been made to identify Yungara private railways or tourist lines being Hattah Margooya Impimi Koorkab VICTORIAN LINES run on closed VR lines Annuello Moolpa Kooloonong Trinita Koimbo Perekerten Showing line status as of March 1999 Natya Bolton Kiamal Coonimur Open BG track Kulwin Manangatang Berambong Tiega Piangil Stony Crossing Ouyen MILES Galah Leitpar Moulamein Cocamba Miralie Tueloga Walpeup Nunga 10 5 0 10 20 30 40 Mittyack Dilpurra Linga Underbool Torrita Chinkapook Nyah West Closed or out of use track Boinka Bronzewing Dhuragoon utye 0 5 10 20 30 40 50 60 T Pier Millan Coobool Panitya Chillingollah Pinnaroo Carina Murrayville Cowangie Pira Niemur KILOMETRES Gypsum Woorinen Danyo Nandaly Wetuppa I BG and 1 SG track Swan Hill Jimiringle Tempy Waitchie Wodonga open station Nyarrin Nacurrie Patchewollock Burraboi Speed Gowanford Pental Ninda Ballbank Cudgewa closed station Willa Turriff Ultima Lake Boga Wakool 2 BG and 1 SG track Yarto Sea Lake Tresco Murrabit Gama Deniliquin Boigbeat Mystic Park Yallakool Dattuck Meatian Myall Lascelles Track converted from BG to SG Berriwillock Lake Charm Caldwell Southdown Westby Koondrook Oaklands Burroin Lalbert Hill Plain Woomelang Teal Pt. -

Railway Map of Victoria, 1890

Northcote Showgrounds Royal Park Jn Somerton Royal Park Flemington Rc SaleyardsNewmarket Sth Morang Braybrook Jn Newmarket Footscray (Main Line) Nth Fitzroy Epping Browns Hill Jn Flemington Bridge Nth Carlton Scotchmere St Footscray West PowderMunro's Sdg Sdg Fitzroy Campbellfield Nth Kensington Macaulay Rd St GeorgesClifton Rd Jn Hill Broadmeadows Thomastown Hay's Sdg Campbellfield Arden St Yd Collingwood Footscray (Suburban) Nth Melbourne Sydenham Glenroy Fawkner East Richmond Brooklyn Yarraville Melbourne Yard Melbourne Nth Coburg Preston (Reservoir) Princes BridgeFlinders St Yd Preston (Regent St) Flinders St Pascoe Vale Bell Park Preston (Murray Rd) Spottiswoode St Albans Coburg Preston (Bell St) Montague Moreland Thornbury Richmond Essendon Port Melbourne Nth Croxton Sth Melbourne Heidelberg Moonee Ponds Brunswick Graham St S Brunswick Middle Ringwood Brick Sdg Freezing Coys Jn Albion Sdg Northcote AlphingtonIvanhoe Sth Yarra Ascot Vale Northcote Sth Fairfield Park Port Melbourne Albert Park Newport Prahran Ringwood Newport Station Deer Park Glenferrie Middle Park Barker's Rd Camberwell Workshops Pier Kew Auburn Hawthorn Mitcham Windsor BurnleyPicnic Box Hill Blackburn TunstallMitcham Brick Sdg Nth Williamstown Surrey Hills Canterbury St Kilda Kew Jn 1 0 1 2 3 Heyington Riversdale Kooyong Scale of Miles Hawksburn Tooronga 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 Laverton Toorak Gardiner Hartwell Armadale Scale of Kilometres Altona Bay Williamstown Rc Swan Hill Glen Iris Ashburton Rly Malvern Williamstown Pier Balaclava Darling Inner & Western Melbourne Caulfield -

Victorian Gorse Control Strategy 2021-26 Victorian Gorse Control Strategy 2021-26

Victorian Gorse Control Strategy 2021-26 Victorian Gorse Control Strategy 2021-26 The Victorian Gorse Taskforce Introduction The Victorian Gorse Taskforce (VGT) was formed in 1999 with the launch of a The Victorian Gorse Taskforce 2 community-based and integrated approach to reducing the impact of gorse Gorse overview 3 The Problem 4 across the landscape. The Solution 5 The Committee currently comprises land managers who have successfully 1 Key Principles 6 controlled gorse on their land and in their communities, as well as 2 Key Outcomes 8 representatives of Landcare groups, local government, agricultural industries and State Government departments. 3 Key Activities 10 4 Annual Task Calendar 12 The Victorian Government funds the VGT to oversee the coordination and implementation of the Victorian Gorse Control Strategy (VGCS). The VGT is 5 Appendix 14 Key Terms 14 committed to ensuring there is a strong emphasis on building community Further Information 15 capacity in gorse control through a mix of extension services, community Abbreviations 15 engagement activities and grants. The VGT encourages the responsible authority to use compliance to support coordinated on-ground action to control gorse. Strategy Authors: Acknowledgements: Published and Authorised by: Disclaimer: Enquiries: Victorian Gorse Taskforce (VGT) The VGT wishes to acknowledge The Victorian Gorse Taskforce, Every effort has been made to ensure VGT Executive Officer, with assistance from Mal Brown the support received from the State February 2021 that the information in this Strategy is Agriculture Victoria, 475-485 (Scarlet Consulting) and Government of Victoria through accurate. The Victorian Gorse Taskforce Mickleham Road, Attwood, VIC 3049 Geoff Park (Natural Decisions Pty Ltd). -

REPO'rt POST OFFICE and Telegllaph DEPARTMENT

1876. VICTORIA. REPO'RT UPON THE~ AFFAIRS OF THE POST OFFICE AND TELEGllAPH DEPARTMENT FOR THE YEAR 1875. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND. ti!! autfJotity: JOHN FERRES, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 14. \ APPROXIMATE COST OF REPORT. .& 8. d. Preparo.tlon-Nat given. Corrections, Proof., and Cancellations 37 0 0 Printing (850 copies) 83 0 0 £120 0 0 REPORTo 'There has been nothing i!l the affairs of the Department during the past year to call for any special remark. The business has steadily increased in all the branches except in the Savings Bank and here, as shown at page 19 of this Report, there has been a falling off. , The Revenue. returns may be considered satisfactory, as they show a very . considerable increase over those of previous years, and the net cost of the Department has been less than it was for 1874 (see Appendix A, page 25). , A large. number of additional post offices have been opened, telegraphic and mail communication have been greatly extended, and other facilities, particulars of which are fully given in the following pages, have been afforded to the public for the transaction of business. ' REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE. Revenue. The gross Postal Revenue for 1874 and 1875 was-including commission on money orders, and excluding fractions- 1874 £154,097 1875 162,132 showing an increase of £8,035, or per cent. "" ,The gr9ss Telegraph Revenue for 1874 and 1875 was- 1874 ",' £42,825 1875 ... 46,995 showing an increase of say 9~ per cent. The total Revenue, Postal, and Telegraph, for 1875, amounted to £209,128, against £196,923 for 1874, showing an increase of £12,205, or 6ir per cent. -

Railway Map of Victoria, 1910

Merri Showgrounds Somerton Royal Park Flemington Rc SaleyardsNewmarket Sth Morang Sunshine Newmarket Angliss' Sdg Epping Nth Carlton Middle Footscray Flemington Bridge Nth Fitzroy Mildura Tottenham West Footscray Abbatoir City Fitzroy Kensington Irymple Footscray Macaulay Merbein NorthcoteClifton Loop Jn Hill Victoria Park Broadmeadows Thomastown Collingwood Hay's Sdg Arden St Yd Nth Richmond Yatpool Nth Melbourne Sydenham West Richmond Greensborough Seddon Glenroy Sth Kensington Jolimont Prahan Council Sdg Brooklyn Fawkner Eltham Yarraville Cemetary Melbourne Yard Spencer St Reservoir Princes BridgeFlinders St Yd Regent Borthwick's Sdg Flinders St Pascoe Vale Nowingi Spotswood Preston Coburg Russell's Sdg East Richmond St Albans Nth Essendon Rosanna Bell Montague Richmond Moreland Thornbury McKenzie & Hollands Sdg Essendon North Port Croxton Hattah Sth Melbourne Heidelberg Friedlander's Sdg Sth Yarra Moonee Ponds Graham Brunswick Northcote Albion Sdg Albion S Brunswick Newport Sth Jn AlphingtonIvanhoe Ascot Vale Fairfield Park Westgarth Thomas' Mill Port Melbourne Albert Park Newport Prahran Newport Station Deer Park Glenferrie Middle Park Camberwell Pier Auburn Workshops Kew HawthornBarker Deepdene Mitcham Ringwood Windsor Federal Manure Sdg Burnley Mont AlbertBox Hill Ouyen Nth Williamstown Balwyn Blackburn Tunstall ShenleyCanterburyChatham St Kilda Surrey Hills East Camberwell 1 0 1 2 3 Riversdale Heyington Golf Links Kooyong Scale of Miles Hawksburn Hartwell Chillingollah Tooronga 1 0 1 2 3 4 5 Burwood Austral Laverton Toorak Gardiner -

Shaping the Pyrenees Information Pack

Shaping the Pyrenees What is your vision for Pyrenees Shire for 2031 and how can we support the different needs of our communities? Pyrenees Shire Community Vision Deliberative Engagement Information Pack Deliberative Engagement Panel to establish a community vision for the Pyrenees Shire, 2021 Meeting at Lexton Hall, 19 Lexton-Ararat Rd, Lexton Vic 3352 10am–3pm Sunday 16th May 10am–3pm Sunday 30th May 10am–3pm Sunday 6th June Refreshments provided: Coffee, tea and water throughout the day Morning tea – 11:30am Lunch – 1:20pm Contact us: Ember Parkin, Community Engagement Officer E [email protected] T 0436 357 038 Acknowledgement of Country Pyrenees Shire is situated on the traditional lands of the Wadawurrung, Dja Dja Wurrung, Eastern Maar and Wotjobaluk tribes. We pay our respects to the customs, traditions and stewardship of the land by the Elders and people of these tribes. About this document and further resources This document provides a snapshot of Pyrenees Shire area. It examines who we are, how we live and work, and contains information on some of the social, demographic, environmental and economic features of our Shire. The information contained within draws on a range of sources, listed below: • 2016 Census data, Australian Bureau of Statistics Census | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) • 2016 ABS Socio-economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) SEIFA (abs.gov.au) • Pyrenees Community Profile & Economic Profile, REMPLAN Region Explorer | REMPLAN (app.remplan.com.au) • Vic Health Indicators – LGA Profiles Pyrenees -

Central Goldfields Shire Council Leisure Services Guide 2021 INDEX

Central Goldfields Shire Council Leisure Services Guide 2021 INDEX Animals and Birds 2 Arts and Crafts 3 Cemetery Trusts 5 Churches 7 Community Groups 11 Community Markets 15 Country Women's Association 17 Dance 18 Emergency Services 19 Film 22 Fitness 23 Guides and Scouts 24 Halls 25 Health 30 Historic Societies & Museums 31 Hobbies 33 Kindergartens 36 Library Services 38 Music 39 Neighbourhood Centres 40 Playgroups 41 Returned Services Groups 42 Schools 44 Senior Citizens Clubs 46 Service Clubs 47 Social Activities 50 Specialised Education 51 Sports 52 T.O.W.N 69 Theatre 70 Tourism / Information 71 Youth 72 Animals and Birds Golden Wattle Kennel Club Inc. CONTACT PERSON Mrs. Kathy Humphries ADDRESS C/- 295A Lorenzs Road Strathmerton VIC 3641 POSTAL ADDRESS 295A Lorenzs Road PHONE NUMBER 03 5874 5646 / 0419 115 950 EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] WEBSITE Maryborough and District Kennel Club CONTACT PERSON Mrs. Kathy Humphries ADDRESS C/- 295A Lorenzs Road Strathmerton VIC 3641 POSTAL ADDRESS 295A Lorenzs Road PHONE NUMBER 03 5874 5646 / 0419 115 950 EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] WEBSITE Maryborough Pigeon Club CONTACT PERSON Peter Knowles ADDRESS 6 Poole Street Maryborough VIC 3465 POSTAL ADDRESS 94 Gillies Street PHONE NUMBER 0433 565 136 EMAIL ADDRESS WEBSITE Maryborough Pigeon Fanciers Inc. CONTACT PERSON Nicholas Jolley ADDRESS Poultry Pavilion, Carisbrook Showgrounds Lexton VIC 3352 POSTAL ADDRESS Po Box 70 PHONE NUMBER 0422 556 234 EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] WEBSITE 2 Arts and Crafts Central Goldfields Art Gallery CONTACT PERSON Helen Kaptein ADDRESS Art Gallery, 1 Neill Street, Maryborough Maryborough VIC 3465 POSTAL ADDRESS PO Box 194 PHONE NUMBER 5461 6600 EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] WEBSITE https://linktr.ee/CGArtGallery DISABLED FACILITES Yes Church of Christ Busy Bees Craft Group CONTACT PERSON Mrs Mary Witnish ADDRESS Cnr. -

Central Highlands Water

2012/2013 ANNUAL REPORT OUR SERVICE AREA Navarre Redbank Havelock Timor Landsborough Bowenvale Alma Maryborough Centenary Reservoir Tullaroop Sugarloaf Avoca Reservoir Reservoir Bung Bong Craigie Lead Daisy Hill Dam Majorca Amphitheatre Talbot Talbot Reservoir Lexton Lexton Maryborough Reservoir Reservoir Clunes Hepburn Springs Smeaton Hepburn Reservoir Waubra Daylesford Kingston Broomfield Bullarto Reservoir Learmonth Newlyn Lake Creswick Beaufort Learmonth Reservior Cosgrave Reservoir Dean Burrumbeet Miners Rest Dean Blackwood Lake White Swan Reservoir Burrumbeet Reservoir Wilson’s Moorabool Ballarat Reservoir Reservoir Colbrook Gong Gong Reservoir Reservoir Kirk’s Wallace Bungaree Carngham Haddon Reservoir Gordon Snake Valley Ballan Lal Lal Smythesdale Reservoir Pittong Buninyong Scarsdale Napoleons Skipton Linton Enfield Dereel LEGEND Corindhap Water pipeline Rokewood Recycled water Water reclamation plants Water treatment plants Major roads Lakes and reservoirs Water district 0 4.75 9.5 19 Kilometres Sewer district 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2012/13 CONTENTS Section 1 – About uS Section 4 – performAnce Our Profile 04 Financial Performance 21 Facts and Figures 04 Summary of Financial Results 21 What We Do 04 Major Works and Contracts 22 Our History 05 Consultancies over $10,000 22 What Guides Us 06 Consultancies under $10,000 22 From Our Chair and Managing Director 07 Performance Report 24 Our Key Events 08 Objectives Report 28 Environmental Sustainability 29 Section 2 – Supply informAtion Social Sustainability 34 Corporate Water Consumption -

PYRENEES Nature Conservation Conservation Park Park CELLAR DOORS

To St Arnaud, Kara Kara Estate North 0 4 8 12 km Stuart Mill Dalyenong Nature PYRENEES Nature Conservation Conservation Park Park CELLAR DOORS STUART MILL Amherst Winery F5 Blue Pyrenees Estate D4 Dalwhinnie Wines B3 WINJALLOK Dogrock Winery A4 Equus@Moonambel C3 Forest Gate Estate E4 MOYREISK Grape Farm Winery B3 ARCHDALE Gwynnyth Vineyard B3 JUNCTION Kara Kara Estate B1 St Arnaud Lamplough Estate E5 Range Michael Unwin Wines D8 National Park Mitchell Harris Wines Ballarat Central Mount Avoca Winery D4 Peerick Vineyard B3 Quoin Hill F7 Romantic Vineyard F5 Sally’s Paddock Redbank Winery C2 NATTE YALLOCK St Ignatius E4 STAWELL-AVOCA RD Redbank-Natte Yallock Rd Summerfield Wines C3 d R h g BARKLY M d Taltarni Vineyards B3 u oona ck R o mbel-Nat llo r te Ya Warrenmang Vineyard C3 o b REDBANK s Wimmera Hills Winery C5 d n a Taltarni Rd L C275 Frenchmans-St Arnaud Rd C221 McAdams Ln MARYB OROU GH MOONAMBEL -S FRENCHMANS T A R N A U B220 D R Punton Rd D Black Mares Ln HOMEBUSH Landsborough Nature Conservation C241 WARRENMANG Rd Reserve ang nm rre Susans Ln LANDSBOROUGH Glenlofty-Wa L PERCYDALE a n d s Percydale Rd To Maryborough b o Sims Ln ro u g h -E l mh Vinoca Rd Ararat-St Arnaud Rd d ur R Redpath Rd Paddys Range Slaughterhouse Rd s g Homebush Rd B180 t n State Park R a d Boundary Track nm re AVOCA Boundary Rd r a Dawsons Rd W - y B180 ft lo n e l G Bung Bong Degraves Rd Nature NOWHERE Conservation GLENLOFTY CREEK Reserve d R k e e r GLENPATRICK C Rd Avoca Rd e k e Caralulup Rd r reenhill Cre CROWLANDS lough-G he Lamp w o Lillicur Rd N -

Wander the Pyrenees Wine Region

To St Arnaud, Kara Kara Estate North 0 4 8 12 km Stuart Mill Dalyenong PYRENEES Nature Nature Conservation Conservation Park Park CELLAR DOORS STUART MILL Amherst Winery F5 Bigibila Winery C3 Blue Pyrenees Estate D4 WINJALLOK Dalwhinnie Wines B3 Dogrock Winery A4 Equus@Moonambel C3 MOYREISK Forest Gate Estate E4 ARCHDALE Grape Farm Winery B3 JUNCTION Gwynnyth Vineyard B3 St Arnaud Kara Kara Estate B1 Range Lamplough Estate E5 National Park Michael Unwin Wines D8 Mitchell Harris Wines Ballarat Central Mount Avoca Winery D4 Peerick Vineyard B3 Quoin Hill F7 Sally’s Paddock Redbank Winery C2 NATTE YALLOCK St Ignatius E4 STAWELL-AVOCA RD Redbank-Natte Yallock Rd Summerfield Wines C3 d R h g BARKLY M d Taltarni Vineyards B3 u oona ck R o mbel-Nat llo r te Ya Warrenmang Vineyard C3 o REDBANK b s Wimmera Hills Winery C5 d n a Taltarni Rd & Mrs Bakers Still House L C275 Frenchmans-St Arnaud Rd C221 McAdams Ln MARYBO ROU GH FRENCHMANS MOONAMBEL -ST A R N A U B220 D R Punton Rd D Black Mares Ln HOMEBUSH Landsborough Nature Conservation C241 WARRENMANG Rd Reserve ang nm rre Susans Ln LANDSBOROUGH Glenlofty-Wa L PERCYDALE a n d To Maryborough s Percydale Rd b o Sims Ln ro u g h -E l mh Vinoca Rd Ararat-St Arnaud Rd d ur R Redpath Rd Paddys Range Slaughterhouse Rd s g Homebush Rd B180 t n State Park R a d Boundary Track nm e r AVOCA Boundary Rd r a Dawsons Rd W - y B180 ft lo n e l G Bung Bong Degraves Rd Nature NOWHERE Conservation GLENLOFTY CREEK Reserve d R k e e r GLENPATRICK C Rd Avoca Rd e k ee Caralulup Rd r reenhill Cr CROWLANDS lough-G he