Both Sides, Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephanie Orfano Is the Social Science Librarian at the Downtown Oshawa Branch of the University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT)

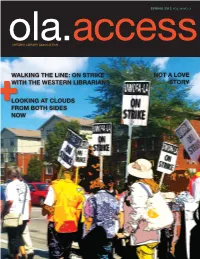

SPRING 2012 vol.18 no. 2 ola.ontario library association access WALKING THE LINE: ON STRIKE NOT A LOVE WITH THE WESTERN LIBRARIANS STORY LOOKING AT CLOUDS FROM BOTH SIDES NOW PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 1 12-03-31 1:11 PM Call today to request your Free catalogue! • Library Supplies • Computer Furniture • Office Furniture • Library Shelving • Book & Media Display • Reading Promotions • Early Learning • Book Trucks • Archival Supplies Call • 1.800.268.2123 Fax • 1.800.871.2397 Shop Online • www.carrmclean.ca PrintOLA_Access18.2Spring2012FinalDraft.indd 2 12-03-31 1:11 PM spring 2012 18:2 contents Features Call today to request Features your Free 11 Risk, Solidarity, Value 21 La place de la bibliothèque publique dans la catalogue! by Kristin hoffmann culture franco-ontarienne During the recent strike by librarians at the University of par steven Kraus Western Ontario, Kristin Hoffmann learned a lot about Vive les bibliothèques publiques du Grand Nord! Steven • Library Supplies her profession, her colleagues and herself. Kraus fait témoignage du rôle que joue la bibliothèque publique dans la promotion de la francophonie. • Computer Furniture 14 Not a Love Story by lisa sloniowsKi 22 Cloudbusting Creating an archive of feminist pornography raises by nicK ruest & john finK • Office Furniture many questions about libraries, librarians, our values and Is all this "cloud" hype ruining your sunny day? Nick • Library Shelving our responsibilities. Lisa Sloniowski guides us through this Ruest and John Fink clear the air and make it all right. The controversial area. forecast is good. • Book & Media Display 18 Visualizing Your Research 24 Governance 101: CEO Evaluation by jenny marvin by jane HILTON • Reading Promotions GeoPortal from Scholars Portal won this year's OLITA As our series on governance continues, Jane Hilton focuses Award for Technological Innovation. -

012521-DRAFT-Bothsidesnow

Both Sides Now: Singer-Songwriters Then and Now An Etz Chayim Fifth Friday SHABBAT SERVICE Kabbalat Shabbat • Happy • Shower the People You Love With Love L’Cha Dodi (to Sweet Baby James) Bar’chu • Creation: Big Yellow Taxi • Revelation: I Choose Y0u Sh’ma • Both Sides Now + Traditional Prayer • V’ahavta: All Of Me • Redemption: Brave Hashkiveynu / Lay Us Down: Beautiful Amidah (“Avodah” / Service) • Avot v’Imahot: Abraham’s Daughter • G’vurot: Music To My Eyes • K’dushat haShem: Edge Of Glory • R’Tzeih: Chelsea Morning • Modim: The Secret Of LIfe • Shalom: Make You Feel My Love (instrumental & reflection) D’Var Torah • Miriam’s Song Congregation Etz Chayim Healing Prayer: You’ve Got a Friend Palo Alto, CA Aleynu Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky Mourners’ Kaddish: Fire And Rain + Traditional Prayer Birchot Hamishpachah / Parents Bless their Children: Circle Game + Inclusive Blessing of Children Closing Song: Adon Olam (to Hallelujah) Both Sides Now Shabbat, 1/29/21 • Shabbat Evening Service, page 1 Kavannah for Our Service For this Fifth Friday Shabbat service we will experience songs by a diverse array of singer- songwriters in place of many of our traditional prayers. The intent is to lift up the prayers by viewing them through a new lens, and perhaps gain new insight into beloved, contemporary songs, whether familiar or new to us. “Both Sides Now” speaks to several relevant themes in our service and in our hearts: • This week’s Torah portion, B’Shallah, begins with our Israeilite ancestors in slavery, on one side of the Sea of Reeds and ends with them as a newly freed people on the other side. -

Scholastic Inc. Out-Of-Print Notification: Pw Advertisement

SCHOLASTIC INC. OUT-OF-PRINT NOTIFICATION: PW ADVERTISEMENT MAY 1, 2006 RETURNS DUE BY AUGUST 28, 2006 Please note: other editions or formats of these titles may exist in print under different ISBNs. ISBN Title 0590338730 ACTS OF LOVE (HC) 0590435469 ADVENTURES OF BOONE BARNABY, THE (HC) 0590445855 ALBIE THE LIFEGUARD (HC) 0590434284 ALICE AND THE BIRTHDAY GIANT (HC) 0590403206 ALIENS IN THE FAMILY (HC) 0590443828 ALIGAY SAVES THE STARS (HC) 0590432125 ANGELA AND THE BROKEN HEART (HC) 0590417266 ANGELA, PRIVATE CITIZEN (HC) 0590443046 ANNA PAVLOVA BALLET'S FIRST WORLD S TAR (HC) 0590478699 AS LONG AS THE RIVERS FLOW (HC) 0590298798 AUTUMN LEAVES (HC) 059022221X BABCOCK (HC) 0590443755 BACKYARD BEAR (HC) 0590601342 BAD GIRLS (HC) 0590601369 BAD, BADDER, BADDEST (HC) 0590427296 BATTER UP! (HC) 0590405373 BEAUTY AND THE BEAST (HC) 0590430211 BEYOND THE CELLAR DOOR (HC) 059041707X BIG AND LITTLE (HC) 0590426222 BIG SARAH'S LITTLE BOOTS (HC) 0590405527 BLACK SNOWMAN, THE (HC) 0590427709 BLITZCAT (HC) 0590433091 BLOODING, THE (HC) 0590601970 BLUE AND THE GRAY, THE (HC) 0590434489 BLUE SKYE (HC) 0590411578 BOATS (HC) 0590407104 BORN INTO LIGHT (HC) 059041237X BORN TO RUN: A RACEHORSE GROWS UP ( HC) 059046843X BOSSY GALLITO, THE (HC) 0590456687 BOTH SIDES NOW (HC) 0590461680 BOY WHO SWALLOWED SNAKES, THE (HC) 0590448161 BSC #01 : KRISTY'S GREAT IDEA (HC) 0439399327 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS #3 THAT’S NO PUDDLE THAT'S ANGELA 0439487196 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS THE EMPEROR OF HOVERBOARD PARK 0439399645 BUTT UGLY MARTIANS DEADLY DREAMS DOCTOR DAMAGE 0439375622 -

Making the Transition from Outside to In-House Counsel Bethany L

Both Sides Now: Making the Transition from Outside to In-House Counsel Bethany L. Appleby & Gary R. Batenhorst I. Introduction Many in-house lawyers for franchise companies began their careers at law firms where they gained experience representing these same franchise companies. For a vari- ety of reasons, lawyers at various stages of their careers may find it more appealing to move to an in-house posi- tion. In this article, two long-time members of the ABA Forum on Franchising, who have worked both in-house and for law firms, discuss the differences between work- Ms. Appleby ing for franchised companies directly as opposed to rep- resenting these companies at law firms. Although most of the discussion in this article focuses on in-house law departments for franchisors, many of the issues dis- cussed also are relevant for in-house lawyers working in the law department of a multi-unit franchisee, including those with franchises in multiple concepts. II. Backgrounds of the Authors Mr. Batenhorst Bethany Appleby received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Yale University, magna cum laude, and graduated with highest honors from The University of Connecticut School of Law. Shortly after finishing law school, she joined the New Haven office of Wiggin and Dana LLP, where she eventually became a litigation partner and co-chaired the firm’s Franchise and Distribution Prac- tice Group. After almost twenty years of representing the Subway® restaurant franchisor in litigation, arbitration, and other matters as outside counsel, she Bethany L. Appleby ([email protected]) is a member of Appleby & Corcoran, LLC, in New Haven, Connecticut, and focuses her practice on franchise and business law litigation. -

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting

Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission 05 February 2021 at 10:00 AM Virtual Meeting 1000 (5) CALL TO ORDER Chairman Sam Petrovich Moment of Silence Vice-Chairman Nick Taylor Pledge of Allegiance Chairman Sam Petrovich 1005 (5) Commission Introduction Chairman Sam Petrovich 1010 (3) Oath of Office MG Mark Schindler Robert Forbes- AMVETS 1013 (3) Approval of 4 December meeting minutes REQUIRES A VOTE 1016 (10) DMVA Military Update MG Mark Schindler 1026 (15) VISN 4 Mr. Tim Liezert OLD BUSINESS NEW BUSINESS 1041 (5) DMVA, Policy, Planning & Legislative Affairs Mr. Seth Benge 1046 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Veterans Homes Mr. Rich Adams 1056 (10) DMVA, Bureau of Programs, Initiatives, Reintegration and Outreach (PIRO) Mr. Joel Mutschler SC 1106 (4) Approval of Programs Report (Report provided by DMVA) REQUIRES A VOTE 1110 (5) Act 66 Committee report Mr. Anthony Jorgenson 1115 (5) RETX Committee report Mr. Justin Slep 1120 (5) Legislative Committee report Chairman Sam Petrovich 1125 (5) Pensions & Relief/Grave markings Committee report Ms. Connie Snavely 1135 (10) Member-at-Large Committee Chairman Sam Petrovich 1145 (10) Good of the Order Chairman Sam Petrovich 1155 (5) Next Meeting: April 2, 2021 Webex Virtual 1200 ADJOURNMENT Chairman Sam Petrovich RETIRING OF COLORS Chairman Sam Petrovich State Veterans Commission Meeting Minutes December 4, 2020 10:00 AM to 11:48 AM Webex Video Teleconference Call to Order Chairman Samuel Petrovich The Pennsylvania State Veterans Commission (SVC) meeting was called to order at 10:00 AM by Chairman Samuel Petrovich. Moment of Silence and Pledge of Allegiance The meeting was opened with a moment of silence for the upcoming 79th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance led by Chairman Samuel Petrovich. -

Fall 2021 Class Schedule

Online Learning, Leading, and Interacting | Community Care Letters | Learning Enrichment Groups | Member Moderators Fall 2021 Class Schedule For the Love of Learning University-quality, non-credit classes for members ages 50+ lifelonglearning.asu.edu Our Mission Registration The mission of OLLI at ASU is to provide learning Visit our website lifelonglearning.asu.edu/registration to experiences and a community where adults ages register online! 50+ engage in non-credit, university-quality classes, member-driven programs, campus-based learning Great news: OLLI at ASU staff are now able to take credit opportunities, and pathways to public service. card payments over the phone. Staff still will be unable to accept checks/cash by mail in Fall 2021. Our Vision $20 Fall Semester As an exemplar of global best practices for Membership Fee innovative lifelong learning, OLLI at ASU creates multiple intentional pathways for transformative A one-time, per-semester membership fee entitles you to connections and learning, inside and outside of its register and take as many classes as you wish. community of learners. Anyone 50+ can become a member! You become a member at the time you register for classes each semester. Membership fees are paid each semester at the time of Our Values registration. Active Participation, Community Commitment, Access and Inclusion, Sustainable Foundations, + Class Fees Trust and Respect, Intentional Innovation, E S Fees are noted in the class descriptions. Classes cost and mpathetic ervice $14/session and run between 1-5 sessions. Important Note Locations Registration for membership and class fees is per-person, OLLI at ASU is now offering in-person, hybrid, and not per-household. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Both Sides As They Seek Issues That Can Be Used to Raise the Stakes and Im- Ages That Can Be Readily Manipulated

Current Anthropology Volume 43, Number 4, August–October 2002 ᭧ 2002 by The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. All rights reserved 0011-3204/2002/4304-0004$2.50 wonders of genetic modification are lauded in op-ed pages, brochures, and coloring books. Since 1998, the most intense rhetorical battle lines of CA✩ FORUM ON the genetic-modification wars have moved south to focus on food security in developing countries (Moffat 1999; ANTHROPOLOGY IN PUBLIC Paarlberg 2000, 2001; Pinstrup-Andersen and Shiøler 2001). This emphasis is strategic for both sides as they seek issues that can be used to raise the stakes and im- ages that can be readily manipulated. Nowhere is the Both Sides Now war as hotly contested as in India. India offers gaunt children to support industry’s claims of food shortages and impoverished smallholders to dramatize critics’ Fallacies in the Genetic- warnings about endangering seed saving. It offers well- developed corporate and public biotechnology sectors Modification Wars, and some of the world’s most savvy green activists. It offers stories of cotton farmers committing suicide by Implications for Developing the hundreds that both industry and its opponents claim Countries, and Anthropological to support their case (Stone 2002a). Anthropologists should be gratified to see issues of Perspectives1 farming, society, and technological change in developing countries thrust into the global gaze, but the move south has exacerbated an already polarized issue, ushering in by Glenn Davis Stone2 a Golden Age of misinformation. Anthropology needs to follow this crucial debate and to contribute to it.4 My focus here is on the core problem of the feeding of the growing populations in the developing world. -

Adjusting Worship During the Pandemic in This Issue of in Tempo

abc efghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz in tempo 0-25-100-0 100-22-22-0 0-80-100-0 a practical resource for Lutheran church musicians Association of Lutheran 2020, No. 2 Church Musicians l alcm.org Adjusting Worship during the Pandemic In this issue of In Tempo: Adjusting Worship A Perspective during the Pandemic 1 0-25-100-0by Tim Getz 100-22-22-0 0-80-100-0 WELS Worship and t Grace Lutheran Church in doing on this one occasion. Just COVID-19 4 Palo Alto, CA, we wanted to writing about that could be an entire akeep things as much the same article, but my overall impression is as possible, to keep a feeling of that Zoom would not be an effective Lenten and Easter continuity, provide a solid rock, and medium for worship on a regular Services in a Pandemic 6 help people feel closely connected basis. to their church home The Retired Church Musician and church family. We Subbing: A Brief Guide 8 are very fortunate to have a video record- Children’s Choir ing ministry already, Seasons 10 and we already have six cameras discreetly installed around our Both Sides Now worship space, so Five (More) Things that the only new hoop Cantors Would Like to jump through to Tell Pastors 14 was going “live.” We use YouTube as our Organ Maintenance platform, and people access the services via Which C? 16 our church website each Sunday at 10:00 Interview with a.m. In addition to all a Church Musician Sundays, we also pro- John Jahr 18 duced live broadcasts on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday evenings. -

'That's How It's Supposed to Make You Feel': Talking with Audiences About

. Volume 9, Issue 2 November 2012 ‘That’s how it’s supposed to make you feel’: Talking with audiences about ‘Both Sides Now’ and Love Actually Lauren Anderson, Massey University, New Zealand Abstract Exploring patterns of response across four semi-structured individual interviews, this article outlines some of the different ways that people heard and related to Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both Sides Now’ as it appeared in the soundtrack to Richard Curtis’ Love Actually (2003). The interviews were designed to explore how participants’ ways of ‘knowing’ the song connected with their ways of responding to the film, its characters, its structural organisation, and so forth. Analysis focuses on the kinds of knowledge the participants made relevant in their talk, and outlines what participants did with that knowledge as they discussed both the song and the scene from Love Actually, before finally considering what ‘Both Sides Now’ achieves for these participants within this excerpt of film. Both song and scene were variously located within the participants’ understandings of their life-worlds and identities: in this way, I argue, they present themselves as more or less “connected” knowers (Hermes, 1995) who discursively manage their involvement with the film and its soundtrack in complex ways. Keywords: popular music, film, soundtrack, audience, interview. Introduction: the research project and research methods Although audiences routinely hear popular music in cinematic contexts, the processes by which they make sense of the soundtrack are rarely discussed. My doctoral research sought to explore how audiences hear and relate to popular songs in films, and the interviews that form the basis of this article were the second phase of that project (Anderson, 2009). -

Inspired by Joni - the Albums

Inspired by Joni - The Albums Compiled by: Simon Montgomery, © 2006 Please send comments, corrections or additions to: [email protected] Latest Update: May 23, 2021 Illustration from The Music Of Joni Mitchell Songbook Published by C.H. Hansen Publications All rights reserved. This material may not, in whole or part, be copied, reproduced, photocopied, translated, recorded, or reduced to any electronic medium, machine readable format or mechanical means without the express consent, in writing, from the specific lawful copyright holder. 1974 Sara Smith Sings The Best of A Tribute To Joni Mitchell Delmar #3013 (8 Track Cartridge) 1. Raised On Robbery 2. Woodstock 3. You Turn Me On, I'm A Radio 4. Chelsea Morning 5. California 6. Carey 7. The Circle Game 8. Night In The City 9. He Played Real Good For Free 1994 Back to the Garden – A Tribute to Joni Mitchell Intrepid Records #N21-00016 - Canada 01. Free Man In Paris Big Faith 02. This Flight Tonight Sara Craig 03. Carey Universal Honey 04. Big Yellow Taxi Lorraine Scott 05. Black Crow Molly Johnson 06. The Beat Of Black Wings Andy Stochansky 07. Shades Of Scarlett Conquering Martha And The Muffins 08. The Hissing Of Summer Lawns Funky Bummer featuring Anne Beadle 09. River Hugh Marsh, Jonathan Goldsmith, Rob Piltch, Martin Tielli 10. You Turn Me On, I'm A Radio Kurt Swinghammer 11. Coyote Spirit Of The West 12. Woodstock W.O.W. 13. Night In The City Jenny Whiteley 14. A Case Of You Sloan 15. Blonde In The Bleachers Squiddly featuring Maria Del Mar 16. -

Moniek Van Der Kallen. 0209082

Moniek van der Kallen Master thesis Film and Television Sciences Utrecht Tutor: Ansje van Beusekom Second reader: Rob Leurs Reader with English as first language: Andy McKenzie How to end the season of a formulaic series. A comparative analysis of the series HOUSE MD and VERONICA MARS about the recurring conflict in the narrative lines of television series’ season finales: resolution versus continuity. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.…………………………....………………………..…..1 KEYWORDS………………………………………………………...1 INTRODUCTION.……………………..………………………..…..2 METHOD ……………………………………..…………………......4 Story levels ……………..………….…………………………………………...….4 The WOW-method………………………….…………………………..……….…5 The story steps of the Ruven & Batavier Schedule ……………………………….6 THEORY: SERIES, SERIALS AND SOAP OPERAS …………..8 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF SOAP OPERAS ………….....…………...…………....14 Narrative subjects ………………………………………………..……..………...14 Narrative structures ….............……………………………………..…………….15 The organization of time ........................................................................................16 1. NARRATIVE STRATEGIES IN HOUSE MD ...…………..…19 EPISODE 1.01 PILOT. Building expectations for the series ..........................................19 Characteristics of a pilot of a series. Introducing the characters, creating expectations…………………………………..………………..……......19 Story endings…..…………………………………..……………………….…....24 Promises for future conflict……….………………..…………………………….26 EPISODE 1.22 THE HONEYMOON. Starting new narratives instead of ending them..27 Introduction a new romantic narrative,