4 Grand Strategists and the Air and Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Combined Chiefs of Staff and the Public Health Building, 1942–1946

The Combined Chiefs of Staff and the Public Health Building, 1942–1946 Christopher Holmes The United States Public Health Service Building, Washington, DC, ca. 1930. rom February 1942 until shortly after the end of World War II, the American Fand British Combined Chiefs of Staff operated from a structure at 1951 Constitution Avenue Northwest in Washington, DC, known as the Public Health Building. Several federal entities became embroiled in this effort to secure a suitable meeting location for the Combined Chiefs, including the Federal Reserve, the War Department, the Executive Office of the President, and the Public Health Service. The Federal Reserve, as an independent yet still federal agency, strove to balance its own requirements with those of the greater war effort. The War Department found priority with the president, who directed his staff to accommodate its needs. Meanwhile, the Public Health Service discovered that a solution to one of its problems ended up creating another in the form of a temporary eviction from its headquarters. Thus, how the Combined Chiefs settled into the Public Health Building is a story of wartime expediency and bureaucratic wrangling. Christopher Holmes is a contract historian with the Joint History and Research Office on the Joint Staff at the Pentagon, Arlington, Virginia. 85 86 | Federal History 2021 Federal Reserve Building In May 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began preparing the nation for what most considered America’s inevitable involvement in the war being waged across Europe and Asia. That month, Roosevelt established the National Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense, commonly referred to as the Defense Commission. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

Additional Historic Information the Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish

USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Additional Historic Information The Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish AMERICA STRIKES BACK The Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942 was the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands during WWII. The mission is notable in that it was the only operation in which U.S. Army Air Forces bombers were launched from an aircraft carrier into combat. The raid demonstrated how vulnerable the Japanese home islands were to air attack just four months after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. While the damage inflicted was slight, the raid significantly boosted American morale while setting in motion a chain of Japanese military events that were disastrous for their long-term war effort. Planning & Preparation Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Roosevelt tasked senior U.S. military commanders with finding a suitable response to assuage the public outrage. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult assignment. The Army Air Forces had no bases in Asia close enough to allow their bombers to attack Japan. At the same time, the Navy had no airplanes with the range and munitions capacity to do meaningful damage without risking the few ships left in the Pacific Fleet. In early January of 1942, Captain Francis Low1, a submariner on CNO Admiral Ernest King’s staff, visited Norfolk, VA to review the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, USS Hornet CV-8. During this visit, he realized that Army medium-range bombers might be successfully launched from an aircraft carrier. -

OH-486) 345 Pages OPEN

Processed by: TB HANDY Date: 4/30/93 HANDY, THOMAS T. (OH-486) 345 pages OPEN Assistant Chief of Staff, Operations Division (OPD), U.S. War Department, 1942-44; Deputy Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, 1944-47. DESCRIPTION: Interview #1 (November 6, 1972; pp 1-47) Early military career: Virginia Military Institute; joins field artillery; service in France during World War I; desire of officers to serve overseas during World Wars I and II; reduction to permanent rank after World War I; field artillery school, 1920; ROTC duty at VMI, 1921-25; advanced field artillery course at Fort Sill; Lesley J. McNair; artillery improvements prior to World War II; McNair and the triangular division; importance of army schools in preparation for war; lack of support for army during interwar period; Fox Conner. Command and General Staff School at Leavenworth, 1926-27: intellectual ability of senior officers; problem solving; value of training for development of self-confidence; lack of training on handling personnel problems. Naval War College, 1936: study of naval tactics and strategy by army officers. Comparison of Leavenworth, Army War College and Fort Sill: theory vs. practical training. Joseph Swing: report to George Marshall and Henry Arnold on foul-up in airborne operation in Sicily; impact on Leigh- Mallory’s fear of disaster in airborne phase of Normandy invasion. Interview #2 (May 22, 1973; pp 48-211) War Plans Division, 1936-40: joint Army-Navy planning committee. 2nd Armored Division, 1940-41: George Patton; role of field artillery in an armored division. Return to War Plans Division, 1941; Leonard Gerow; blame for Pearl Harbor surprise; need for directing resources toward one objective; complaint about diverting Normandy invasion resources for attack on North Africa; Operation Torch and Guadalcanal as turning points in war; risks involved in Operation Torch; fear that Germany would conquer Russia; early decision to concentrate attack against Germany rather than Japan; potential landing sites in western Europe. -

Operation ICEBERG: How the Strategic Influenced the Tactics of LTG Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr

Operation ICEBERG: How the Strategic Influenced the Tactics of LTG Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr. at Okinawa By Evan John Isaac A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of History Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Approved by Mark Sheftall, Chair, Associate Professor of History David Carter, Associate Professor of History Keith Hebert, Assistant Professor of History Abstract The Okinawan campaign was World War II’s last major offensive operation. Selected as the last position for which to organize the invasion of Japan, the scale and intensity of combat led to critical accounts from journalists accustomed to the war’s smaller amphibious operations in 1943 and 1944. This criticism carried forward to later historical analysis of the operation’s ground commander, Army Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. Labeled as inexperienced and an Army partisan, Buckner was identified as a major contributor to the campaign’s high casualty numbers. This historical analysis has failed to address the impacts of decisions on early war strategy and their impacts to three key strategic factors: a massive shortage of service units, a critical deficit in shipping, and the expansion of strategic bombing in the Pacific. This thesis examines the role that these strategic factors played in influencing the tactical decision making of General Buckner at Okinawa. ii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….....……….ii List of Figures…......…………………………………………...…………………….…iv -

Tokyo Bay the AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II The High Road to Tokyo Bay The AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater Daniel Haulman Air Force Historical Research Agency DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited "'Aý-Iiefor Air Force History 1993 20050429 028 The High Road to Tokyo Bay In early 1942, Japanese military forces dominated a significant portion of the earth's surface, stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Bering Sea and from Manchuria to the Coral Sea. Just three years later, Japan surrendered, having lost most of its vast domain. Coordinated action by Allied air, naval, and ground forces attained the victory. Air power, both land- and carrier-based, played a dominant role. Understanding the Army Air Forces' role in the Asiatic-Pacific theater requires examining the con- text of Allied strategy, American air and naval operations, and ground campaigns. Without the surface conquests by soldiers and sailors, AAF fliers would have lacked bases close enough to enemy targets for effective raids. Yet, without Allied air power, these surface victories would have been impossible. The High Road to Tokyo Bay concentrates on the Army Air Forces' tactical operations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II. A subsequent pamphlet will cover the strategic bombardment of Japan. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. -

10, George C. Marshall

'The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Air Force, Department of Defense or the US Government.'" USAFA Harmon Memorial Lecture #10 “George C. Marshall: Global Commander” Forrest C. Pogue, 1968 It is a privilege to be invited to give the tenth lecture in a series which has become widely-known among teachers and students of military history. I am, of course, delighted to talk with you about Gen. George C. Marshall with whose career I have spent most of my waking hours since1956. Douglas Freeman, biographer of two great Americans, liked to say that he had spent twenty years in the company of Gen. Lee. After devoting nearly twelve years to collecting the papers of General Marshall and to interviewing him and more than 300 of his contemporaries, I can fully appreciate his point. In fact, my wife complains that nearly any subject from food to favorite books reminds me of a story about General Marshall. If someone serves seafood, I am likely to recall that General Marshall was allergic to shrimp. When I saw here in the audience Jim Cate, professor at the University of Chicago and one of the authors of the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, I recalled his fondness for the works of G.A. Henty and at once there came back to me that Marshall once said that his main knowledge of Hannibal came from Henty's The Young Carthaginian. If someone asks about the General and Winston Churchill, I am likely to say, "Did you know that they first met in London in 1919 when Marshall served as Churchill's aide one afternoon when the latter reviewed an American regiment in Hyde Park?" Thus, when I mentioned to a friend that I was coming to the Air Force Academy to speak about Marshall, he asked if there was much to say about the General's connection with the Air Force. -

Happy Father's Day, Teddy Roosevelt

Happy Father’s Day, Teddy Roosevelt Fatherhood and Tragedy Birth of Alice Roosevelt Death of Alice Roosevelt His Daughter His Wife February 12, 1884 February 14, 1884 Second Chance of Happiness Marries Edith Kermit Carow St. George’s Hanover Square, London December 2, 1886 Roosevelt Family 1884 Alice 1887 Theodore 1889 Kermit 1891 Ethel 1894 Archibald 1897 Quentin Quentin, the Baby of the Family At Home Sagamore Hill Long Island Becomes President on September 14, 1901 Family Moves to the White House Alice “I can be President of the United States—or—I can attend to Alice! I cannot possibly do both!” Theodore Roosevelt Theodore, Jr. “In Washington, when father was civil service commissioner, I often walked to the office with him. On the way down he would talk history to me – not the dry history of dates and charters, but the history where you yourself in your imagination could assume the role of the principal actors, as every well- constructed boy wishes to do when interested.” Kermit “The house seems very empty without you and Ted, although I cannot conscientiously say that it is quiet — Archie and Quentin attend to that.” Theodore Roosevelt Letter to Kermit Roosevelt Oyster Bay September 23, 1903 Archie and Quentin “Vice-Mother” “Mother has gone off for nine days, and as usual I am acting as vice- mother. Archie and Quentin are really too cunning for anything. Each night I spend about three- quarters of an hour reading to them.” Theodore Roosevelt Letter to Kermit Roosevelt White House November 15, 1903 “Blessed Quenty-Quee” Ethel “I think you are a little trump and I love your letter, and the way you take care of the children and keep down the expenses and cook bread and are just your own blessed busy cunning self.” Theodore Roosevelt Letter to Ethel Roosevelt White House June 21, 1904 “Ethel administers necessary discipline to Archie and Quentin.” Uncle of the Bride Wedding of Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt March 17, 1905 “With President Roosevelt and St. -

Fireside Chats”

Becoming “The Great Arsenal of Democracy”: A Rhetorical Analysis of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Pre-War “Fireside Chats” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Allison M. Prasch IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Under the direction of Dr. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell December 2011 © Allison M. Prasch 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are like dwarfs standing upon the shoulders of giants, and so able to see more and see further . - Bernard of Chartres My parents, Ben and Rochelle Platter, encouraged a love of learning and intellectual curiosity from an early age. They enthusiastically supported my goals and dreams, whether that meant driving to Hillsdale, Michigan, in the dead of winter or moving me to Washington, D.C., during my junior year of college. They have continued to show this same encouragement and support during graduate school, and I am blessed to be their daughter. My in-laws, Greg and Sue Prasch, have welcomed me into their family as their own daughter. I am grateful to call them friends. During my undergraduate education, Dr. Brad Birzer was a terrific advisor, mentor, and friend. Dr. Kirstin Kiledal challenged me to pursue my interest in rhetoric and cheered me on through the graduate school application process. Without their example and encouragement, this project would not exist. The University of Minnesota Department of Communication Studies and the Council of Graduate Students provided generous funding for a summer research trip to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York. -

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, U.S. Navy Ernest J

Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, U.S. Navy Ernest J. King was born on 23 November 1878 in Lorain, OH. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy from 1897 until 1901, graduating fourth in his class. During his senior year at the Academy, he attained the rank of Midshipman Lieutenant Commander, the highest midshipman ranking at that time. While still at the Academy, he served on the USS San Francisco during the Spanish–American War. While at the Naval Academy, King met Martha Rankin Egerton, whom he married in a ceremony at the Naval Academy Chapel on 10 October 1905. They had six daughters, Claire, Elizabeth, Florence, Martha, Eleanor and Mildred; and then a son, Ernest Jr. After graduation, he served as a junior officer on the survey ship USS Eagle, the battleships USS Illinois, USS Alabama, and USS New Hampshire, and the cruiser USS Cincinnati. King returned to shore duty at Annapolis in 1912. He received his first command, the destroyer USS Terry in 1914, participating in the U.S. occupation of Veracruz. He then moved on to a more modern ship, USS Cassin. World War I: During the war he served on the staff of Vice Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. As such, he was a frequent visitor to the Royal Navy and occasionally saw action as an observer on board British ships. He was awarded the Navy Cross "for distinguished service in the line of his profession as assistant chief of staff of the Atlantic Fleet." After the war, King, now a captain, became head of the Naval Postgraduate School. -

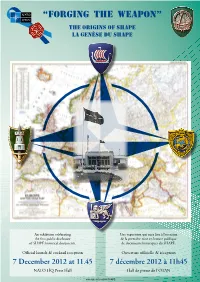

Forging the Weapon: the Origins of SHAPE

“Forging the weapon” the origins oF shape La genèse du shape An exhibition celebrating Une exposition qui aura lieu à l’occasion the first public disclosure de la première mise en lecture publique of SHAPE historical documents. de documents historiques du SHAPE. Official launch & cocktail reception Ouverture officielle & réception 7 December 2012 at 11.45 7 décembre 2012 à 11h45 NATO HQ Press Hall Hall de presse de l’OTAN 1705-12 NATO Graphics & Printing www.nato.int/archives/SHAPE The short film ALLIANCE FOR PEACE (1953) and rare film footage chronicling the historical events related to the creation of SHAPE Le court-métrage ALLIANCE FOR PEACE (1953) et des séquences rares qui relatent les événements historiques concernant la genèse de SHAPE. Forging the weapon The origins of SHAPE The NATO Archives and the SHAPE Historical Office would like to gratefully acknowledge the support of SHAPE Records and Registry, the NATO AIM Printing and Graphics Design team, the NATO PDD video editors, the Imperial War Museum, and the archives of the National Geographic Society, all of whom contributed invaluable assistance and material for this exhibition. Les Archives de l’OTAN et le Bureau historique du SHAPE tiennent à expriment toute leur reconnaissance aux Archives et au Bureau d’ordre du SHAPE, à l’équipe Impression et travaux graphiques de l’AIM de l’OTAN, aux monteurs vidéo de la PDD de l’OTAN, à l’Imperial War Museum et au service des archives de la National Geographic Society, pour leur précieuse assistance ainsi que pour le matériel mis à disposition aux fins de cette exposition. -

General Management Plan, Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites

National Park Service Roosevelt-Vanderbilt U.S. Department of the Interior National Historic Sites Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site General Management Plan 2010 Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site Eleanor Roosevelt National Historic Site Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site General Management Plan top cottage home of fdr vanderbilt mansion val-kill Department of the Interior National Park Service Northeast Region Boston, Massachusetts 2010 Contents 4 Message from the Superintendent Background 7 Introduction 10 Purpose of the General Management Plan 10 Overview of the National Historic Sites 23 Associated Resources Outside of Park Ownership 26 Related Programs, Plans, and Initiatives 28 Developing the Plan Foundation for the Plan 33 Purpose and Significance of the National Historic Sites 34 Interpretive Themes 40 The Need for the Plan The Plan 45 Goals for the National Historic Sites 46 Overview 46 Management Objectives and Potential Actions 65 Management Zoning 68 Cost Estimates 69 Ideas Considered but Not Advanced 71 Next Steps Appendices 73 Appendix A: Record of Decision 91 Appendix B: Legislation 113 Appendix C: Historical Overview 131 Appendix D: Glossary of Terms 140 Appendix E: Treatment, Use, and Condition of Primary Historic Buildings 144 Appendix F: Visitor Experience & Resource Protection (Carrying Capacity) 147 Appendix G: Section 106 Compliance Requirements for Future Undertakings 149 Appendix H: List of Preparers Maps 8 Hudson River Valley Context 9 Hyde Park Context 12 Historic Roosevelt Family Estate 14 FDR Home and Grounds 16 Val-Kill and Top Cottage 18 Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site 64 Management Zoning Message from the Superintendent On April 12, 1946, one year after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death, his home in Hyde Park, New York, was opened to the public as a national his- toric site.