Syria in Crusader Times Conflict and Coexistence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conquest of Arsuf by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects (MSR IX.1, 2005)

REUVEN AMITAI THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM The Conquest of Arsu≠f by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects* A modern-day visitor to Arsu≠f1 cannot help but be struck by the neatly arranged piles of stones from siege machines found at the site. This ordering, of course, represents the labors of contemporary archeologists and their assistants to gather the numerous but scattered stones. Yet, in spite of the recent nature of this "installation," these heaps are clear, if mute, evidence of the great efforts of the Mamluks led by Sultan Baybars (1260–77) to conquer the fortified city from the Franks in 1265. This conquest, as well as its political background and its aftermath, will be the subjects of the present article, which can also be seen as a case-study of Mamluk siege warfare. The immediate backdrop to the Mamluk attack against Arsu≠f was the events of the preceding weeks. At the end of 1264, while Baybars was hunting in the Egyptian countryside, he received reports that the Mongols were heading in force for the Mamluk border fortress of al-B|rah along the Euphrates, today in south- eastern Turkey. The sultan quickly returned to Cairo, and ordered the immediate dispatch of advanced light forces, which were followed by a more organized, but still relatively small, force under the command of the senior amir (officer) Ughan Samm al-Mawt ("the Elixir of Death"), and then by a third corps, together with © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. *I would like to thank Prof. Israel Roll of Tel Aviv University, who conducted the excavations at the site, and was most helpful when he showed us the site. -

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 the Last Crusades. Hello Again

History of the Crusades. Episode 103 The Last Crusades. Hello again. Last week, things didn't go so well for the Latin Christians in the Middle East, with an entire Crusader state, the Principality of Antioch, being effectively wiped off the map following an invasion by the Egyptian Mamluk Sultan Baibars. The Latin Christians of Europe had been viewing events in the Holy Land with concern for some time, and with the fall of Antioch, it was obvious that some urgent assistance was required. More specifically, what was needed of course, was another Crusade. As far back as August 1266 Pope Clement IV had begun to call for a new Crusade. England had been wracked by civil war, but that had come to an end in 1265, and with King Louis IX’s ambitious brother Charles of Anjou securing for himself the Sicilian crown in 1266, the attentions of the people in Europe could finally focus on problems in the Middle East. King Louis of France, now aged in his early fifties, jumped at the chance to redeem the failure of his ill-fated previous Crusade, and on the 25th of March 1267 once again made a public vow to take up the Cross. Also raising their hands to mount a Crusade were Lord Edward of England and King James I of Aragon. Lord Edward was the son of the aging King Henry III of England, and would later become King Edward I. Against his father's wishes. Lord Edward made his Crusading vow in 1268, and many of the noblemen of England, keen to put the trauma of the recent civil war behind them, followed his example. -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - C

Cambridge University Press 0521414113 - The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - c. 1024-c. 1198 Edited by David Luscombe and Jonathan Riley-Smith Index More information INDEX Aachen, 77, 396, 401, 402, 404, 405 Abul-Barakat al-Jarjara, 695, 700 Aaron, bishop of Cologne, 280 Acerra, counts of, 473 ‘Abbadids, kingdom of Seville, 157 Acre ‘Abbas ibn Tamim, 718 11th century, 702, 704, 705 ‘Abbasids 12th century Baghdad, 675, 685, 686, 687, 689, 702 1104 Latin conquest, 647 break-up of empire, 678, 680 1191 siege, 522, 663 and Byzantium, 696 and Ayyubids, 749 caliphate, before First Crusade, 1 fall to crusaders, 708 dynasty, 675, 677 fall to Saladin, 662, 663 response to Fatimid empire, 685–9 Fatimids, 728 abbeys, see monasteries and kingdom of Jerusalem, 654, 662, 664, abbots, 13, 530 667, 668, 669 ‘Abd Allah al-Ziri, king of Granada, 156, 169–70, Pisans, 664 180, 181, 183 trade, 727 ‘Abd al-Majid, 715 13th century, 749 ‘Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar, 155, 158, 160, 163, 165 Adalasia of Sicily, 648 ‘Abd al-Mu’min, 487 Adalbero, bishop of Wurzburg,¨ 57 ‘Abd al-Rahman (Shanjul), 155, 156 Adalbero of Laon, 146, 151 ‘Abd al-Rahman III, 156, 159 Adalbert, archbishop of Mainz, 70, 71, 384–5, ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Ilyas, 682 388, 400, 413, 414 Abelard of Conversano, 109, 110, 111, 115 Adalbert, bishop of Prague, 277, 279, 284, 288, Aberconwy, 599 312 Aberdeen, 590 Adalbert, bishop of Wolin, 283 Abergavenny, 205 Adalbert, king of Italy, 135 Abernethy agreement, 205 Adalgar, chancellor, 77 Aberteifi, 600 Adam of Bremen, 295 Abingdon, 201, 558 Adam of -

RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: Sciences & Economics Review ______

Research Journal of Social Sciences & Economics Review Vol. 2, Issue 1, 2021 (January – March) ISSN 2707-9023 (online), ISSN 2707-9015 (Print) RJSSER ISSN 2707-9015 (ISSN-L) Research Journal of Social DOI: https://doi.org/10.36902/rjsser-vol2-iss1-2021(79-82) Sciences & Economics Review ____________________________________________________________________________________ Analytical Study of Pedagogical Practices of Abul Hasan Ashari (270 AH ...330 AH) * Dr. Hashmat Begum, Assistant Professor ** Dr. Hafiz Muhammad Ibrar Ullah, Assistant Professor (Corresponding Author) *** Dr. Samina Begum, Assistant Professor __________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Abu al Hasan al-Ashari is measured to be a great as well as famous scholar of theology. He competed with philosophers with the power of his knowledge. He was a famous religious scholar of the Abbasi period. During the heyday of Islam, two schools of thought became famous. One school of thought became famous as the Motazilies and the other discipline of thought became known as the Ash'arites. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari remained a supporter of the Mu'tazilites for forty years. Then there was a disagreement with Mu'tazilah about the issue of value. Imam al-Ghazali is one of the leading preachers of his Ash'arite school of thought. Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari inherited a passion for collecting books. As a child, he used to collect books from his hobby. Sometimes there are very difficult places in the path of knowledge, only a real student can pass through these places safely. He has been remembered by the Islamic world in very high words. There was a student who drank the ocean of knowledge but his thirst was not quenched. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

The Berber Identity: a Double Helix of Islam and War by Alvin Okoreeh

The Berber Identity: A Double Helix of Islam and War By Alvin Okoreeh Mezquita de Córdoba, Interior. Muslim Spain is characterized by a myriad of sophisticated and complex dynamics that invariably draw from a foundation rooted in an ethnically diverse populace made up of Arabs, Berbers, muwalladun, Mozarebs, Jews, and Christians. According to most scholars, the overriding theme for this period in the Iberian Peninsula is an unprecedented level of tolerance. The actual level of tolerance experienced by its inhabitants is debatable and relative to time, however, commensurate with the idea of tolerance is the premise that each of the aforementioned groups was able to leave a distinct mark on the era of Muslim dominance in Spain. The Arabs, with longstanding ties to supremacy in Damascus and Baghdad exercised authority as the conqueror and imbued al-Andalus with culture and learning until the fall of the caliphate in 1031. The Berbers were at times allies with the Arabs and Christians, were often enemies with everyone on the Iberian Peninsula, and in the times of the taifas, Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, were the rulers of al-Andalus. The muwalladun, subjugated by Arab perceptions of a dubious conversion to Islam, were mired in compulsory ineptitude under the pretense that their conversion to Islam would yield a more prosperous life. The Mozarebs and Jews, referred to as “people of the book,” experienced a wide spectrum of societal conditions ranging from prosperity to withering persecution. This paper will argue that the Berbers, by virtue of cultural assimilation and an identity forged by militant aggressiveness and religious zealotry, were the most influential ethno-religious group in Muslim Spain from the time of the initial Muslim conquest of Spain by Berber-led Umayyad forces to the last vestige of Muslim dominance in Spain during the time of the Almohads. -

The Seljuks of Anatolia: an Epigraphic Study

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2017 The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study Salma Moustafa Azzam Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Azzam, S. (2017).The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 MLA Citation Azzam, Salma Moustafa. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An Epigraphic Study Abstract This is a study of the monumental epigraphy of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, also known as the Sultanate of Rum, which emerged in Anatolia following the Great Seljuk victory in Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in the year 1071.It was heavily weakened in the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 against the Mongols but lasted until the end of the thirteenth century. The history of this sultanate which survived many wars, the Crusades and the Mongol invasion is analyzed through their epigraphy with regard to the influence of political and cultural shifts. The identity of the sultanate and its sultans is examined with the use of their titles in their monumental inscriptions with an emphasis on the use of the language and vocabulary, and with the purpose of assessing their strength during different periods of their realm. -

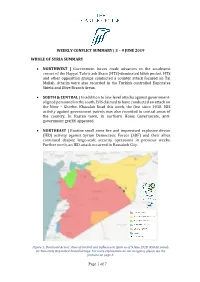

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

Fatimid Material Culture in Al-Andalus: Presences and Influences of Egypt in Al-Andalus Between the Xth and the Xiith Centuries A.D

Fatimid Material Culture in Al-Andalus: Presences and Influences of Egypt in Al-Andalus Between the Xth and the XIIth Centuries A.D. Zabya Abo Aljadayel Dissertation of Master of Archaeology September, 2019 Dissertation submitted to fulfil the necessary requirements to obtain a Master's Degree of Archaeology, held under the scientific orientation of Prof. André Teixeira and Prof.ª Susana Gómez Martínez. 2 | P a g e Zabya Abo aljadayel | 2019 To my family, friends and every interested reader لعائلتي, ﻷصدقائي و لكل قارئ مهتم 3 | P a g e Zabya Abo aljadayel | 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I give my gratitude and love To my dear professors Susana and André for being more than advisors with their patience, kindness and support. To the Global Platform for Syrian Students for giving me the opportunity to come to Portugal to continue my higher education. In particular, I would like to commend the efforts of Dr Helena Barroco for being by my side in the formal and the nonformal situations. To FCSH-UNL for giving me a seat in the faculty. Moreover, to Dr Francisco José Gomes Caramelo and Dr João Soeiro de Carvalho for their kindness and academic support. To my beloved friends in CAM and in all Mértola for well receiving me there as a part of their lovely family. To Dr Susana Calvo Capilla and Dr María Antonia Martínez Núñez for their support. To my mother, I would say that Charles Virolleaud wasn’t entirely right when he said: “Tout homme civilisé a deux patries: la sienne et la Syrie.”. But, should have said: “Tout homme civilisé a trois patries: Sa mère, la sienne et la Syrie.”. -

History of Islam

Istanbul 1437 / 2016 © Erkam Publications 2016 / 1437 H HISTORY OF ISLAM Original Title : İslam Tarihi (Ders Kitabı) Author : Commission Auteur du Volume « Histoire de l’Afrique » : Dr. Said ZONGO Coordinator : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Faruk KANGER Academic Consultant : Lokman HELVACI Translator : Fulden ELİF AYDIN Melda DOĞAN Corrector : Mohamed ROUSSEL Editor : İsmail ERİŞ Graphics : Rasim ŞAKİROĞLU Mithat ŞENTÜRK ISBN : 978-9944-83-747-7 Addresse : İkitelli Organize Sanayi Bölgesi Mahallesi Atatürk Bulvarı Haseyad 1. Kısım No: 60/3-C Başakşehir / Istanbul - Turkey Tel : (90-212) 671-0700 (pbx) Fax : (90-212) 671-0748 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.islamicpublishing.org Printed by : Erkam Printhouse Language : English ERKAM PUBLICATIONS TEXTBOOK HISTORY OF ISLAM 10th GRADE ERKAM PUBLICATIONS Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE ERA OF FOUR RIGHTLY GUIDED CALIPHS (632–661) / 8 A. THE ELECTION OF THE FIRST CALIPH .............................................................................................. 11 B. THE PERIOD OF ABU BAKR (May Allah be Pleased with him) (632–634) ....................................... 11 C. THE PERIOD OF UMAR (May Allah be Pleased with him) (634–644) ............................................... 16 D. THE PERIOD OF UTHMAN (May Allah be Pleased with him) (644–656) ........................................ 21 E. THE PERIOD OF ALI (May Allah be pleased with him) (656-661) ...................................................... 26 EVALUATION QUESTIONS ......................................................................................................................... -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts.