(De)Constructed Gender and Romance in Steven Universe: a Queer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARTOON NETWORK November 2019

CARTOON NETWORK November 2019 MON. TUE. WED. THU. FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 Grizzy and the Lemmings We Bare Bears 4:00 4:30 The Powerpuff Girls Steven Universe 4:30 5:00 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 5:00 5:30 The Pink Panther & Pals Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 5:30 6:00 Thomas and Friends 6:00 HANAKAPPA (J) 6:30 6:30 The Amazing World of Gumball Pingu in the City 6:45 7:00 TEEN TiTANS GO! Uncle Grandpa 7:00 7:30 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 7:30 8:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Tom & Jerry series 8:00 8:30 Oggy & the Cockroaches 11/21~Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 9:00 Tom & Jerry series The New Looney Tunes Show 9:00 9:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings 10:00 Thomas and Friends 11/16~ 11/10 10:30 HANAKAPPA (J) BEN 10 BEN 10 Steven Universe Steven Universe 10:00 10:45 Pingu in the City The Powerpuff Girls The Powerpuff Girls The New Looney Tunes Show The New Looney Tunes Show 11:00 The Powerpuff Girls 11:30 We Bare Bears Eagle Talon The EX(J) 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends 12:00 12:30 HANAKAPPA (J) Barbie Dreamhouse Adventures 12:30 12:45 Pingu in the City 13:00 OK KO: Let's Be Heroes! The Powerpuff Girls 13:00 13:30 Uncle Grandpa Unikitty! 13:30 14:00 The Powerpuff Girls Clarence 14:00 14:30 We Bare Bears BEN 10 14:30 15:00 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries Uncle Grandpa 15:00 15:30 BEN 10 The New Looney Tunes Show 15:30 16:00 TEEN TiTANS GO! Tom & Jerry series 16:00 16:30 Uncle Grandpa 17:00 OK KO: Let's Be Heroes! 17:15 Eagle Talon The DO(J) The Amazing World of Gumball 17:00 17:30 The New Looney Tunes Show 18:00 -

Montréal's Gay Village

Produced By: Montréal’s Gay Village Welcoming and Increasing LGBT Visitors March, 2016 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ÉTUDE SUR LE VILLAGE GAI DE MONTRÉAL Partenariat entre la SDC du Village, la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec › La Société de développement commercial du Village et ses fiers partenaires financiers, que sont la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec, sont heureux de présenter cette étude réalisée par la firme Community Marketing & Insights. › Ce rapport présente les résultats d’un sondage réalisé auprès de la communauté LGBT du nord‐est des États‐ Unis (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, État de New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvanie, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginie, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois), du Canada (Ontario et Colombie‐Britannique) et de l’Europe francophone (France, Belgique, Suisse). Il dresse un portrait des intérêts des touristes LGBT et de leurs appréciations et perceptions du Village gai de Montréal. › La première section fait ressortir certaines constatations clés alors que la suite présente les données recueillies et offre une analyse plus en détail. Entre autres, l’appréciation des touristes qui ont visité Montréal et la perception de ceux qui n’en n’ont pas eu l’occasion. › L’objectif de ce sondage est de mieux outiller la SDC du Village dans ses démarches de promotion auprès des touristes LGBT. 2 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ABOUT CMI OVER 20 YEARS OF LGBT INSIGHTS › Community Marketing & Insights (CMI) has been conducting LGBT consumer research for over 20 years. Our practice includes online surveys, in‐depth interviews, intercepts, focus groups (on‐site and online), and advisory boards in North America and Europe. -

Steven Universe in College Curriculum

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy “I am a Conversation”: Media Literacy, Queer Pedagogy, and Steven Universe in College Curriculum Misty Thomas University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT: The recent cartoon show on Cartoon Network Steven Universe allows for the blending of both queer theory and media literacies to create a pedagogical space for students to investigate and analyze not only queerness, but also normative and non-normative identities. This show creates characters as well as relationships that both break with and subvert what would be considered traditional masculine and feminine identities. Additionally, Steven Universe also creates a space where sexuality and transgender bodies are represented. This paper demonstrates both the presence of queerness within the show and the pedagogical implications for using this piece of media within a college classroom. Keywords: popular culture; Steven Universe; Queer Theory; media literacy; pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 1 Thomas INTRODUCTION Media literacy pedagogy is expanding as new advances and theories are added each year along with recommendations on how these theories can work together. Two of these pedagogical theories are Media Literacies and Queer Pedagogy. This blended pedagogical approach is useful for not only courses in media studies, but also composition classes. Media literacies focus on the use of various forms of media to investigate the role media plays in the creation and reinforcement of identity. Due to this focus on identity representations, media literacy effectively combines with queer pedagogy, which investigates the concepts of normalization within the classroom. -

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

Queer Identities Rupturing Dentity Categories and Negotiating Meanings of Oueer

Queer Identities Rupturing dentity Categories and Negotiating Meanings of Oueer WENDY PETERS Ce projet dPcrit sept Canadiennes qui In the article, "The Politics of constructed by available discourses shpproprient le terme "queerJ'comme InsideIOut," Ki Namaste recom- (Foucault). Below, I describe some orientation sexuelk et en explore ks mends that queer theoreticians pay of the meanings participants as- dzfirentes signt$cations. Leur identiti attention to the diversity of non- cribed to queer, and explore the et expiriencespointent rt. certaines ca- heterosexual identities. I created the ways in which queer was under- tigories sexuelles existantes comme les- following research project through stood and represented by people biennes et hitirosexuelles. my interest in queer theory and a who claim, or have claimed, queer subsequent recognition that queer, as their sexuality identity category. In the 1990s, the term "queer" gained as described in queer theory, is an The first person to email the new acceptance within poststruct- excellent description for my sexu- listserv identified herself as uralistlpostmodernist thought. In ality and gender practices. Since "Stressed!" Stressed wrote often part, this was an attempt to move queer is a term that resists a static about trying to finish her gradu- away from reproducing the hetero- definition, I was curious to see who ate-level thesis, and chose her alias sexist binary of heterosexual and ho- else was claiming queer as an iden- to reflect her current state of mind. mosexual. Queer theory contends that tity category and what it meant for She related how her claiming of in order to challenge heteronorma- them. After sending an email to queer as an identity category came tivity, we need to go beyond replac- friends and various listservs detail- through her coming-out process ing one restrictive category with an- ing my interest in starting an aca- and her reluctance to choose a sexu- other. -

Shifting the Media Narrative on Transgender Homicides

w Training, Consultation & Research to Accelerate Acceptance More SHIFTING THE MEDIA Than NARRATIVE ON TRANSGENDER HOMICIDES a Number MARCH 2018 PB 1 Foreword 03 An Open Letter to Media 04 Reporting Tip Sheet 05 Case Studies 06 Spokespeople Speak Out 08 2017 Data Findings 10 In Memorium 11 Additional Resources 14 References 15 AUTHORS Nick Adams, Director of Transgender Media and Representation; Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response; Sue Yacka-Bible, Communications Director DATA COLLECTION Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response; Sue Yacka-Bible, Communications Director DATA ANALYSIS Arielle Gordon, News and Rapid Response Intern; MJ Okma, Associate Director of News and Rapid Response DESIGN Morgan Alan, Design and Multimedia Manager 2 3 This report is being released at a time in our current political climate where LGBTQ acceptance is slipping in the U.S. and anti-LGBTQ discrimination is on the rise. GLAAD and This report documents The Harris Poll’s most recent Accelerating Acceptance report found that 55 percent of LGBTQ adults reported experiencing the epidemic of anti- discrimination because of their sexual orientation or gender transgender violence in identity – a disturbing 11% rise from last year. 2017, and serves as a companion to GLAAD’s In our online resource for journalist and advocates, the Trump tip sheet Doubly Accountability Project, GLAAD has recorded over 50 explicit attacks by the Trump Administration – many of which are Victimized: Reporting aimed at harming and erasing transgender people, including on Transgender an attempt to ban trans people from serving in the U.S. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

Universidade De Brasília Faculdade De Comunicação Departamento De Audiovisuais E Publicidade Bárbara Ingrid De Oliveira

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE AUDIOVISUAIS E PUBLICIDADE BÁRBARA INGRID DE OLIVEIRA ARAÚJO A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Brasília-DF Junho de 2019 2 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE AUDIOVISUAIS E PUBLICIDADE BÁRBARA INGRID DE OLIVEIRA ARAÚJO A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Monografia submetida à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Audiovisual Orientadora: Prof. Dr. Denise Moraes Brasília-DF Junho de 2019 3 A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Monografia submetida à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Audiovisual Brasília, 2 de julho de 2019. MEMBROS DA BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof. Dra. Denise Moraes Cavalcante, FAC/UnB Orientadora Prof. M.a Emilia Silveira Silbertein Examinadora Prof. M.a Érika Bauer Oliveira Examinadora Prof. Dra. Rose May Carneiro Suplente 4 A todas as mulheres que lutam por um feminismo classista e acessível. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS A minha família, pelo suporte em todos os momentos, desde a formação quando criança até a bagagem necessária para chegar aqui. A Deus, por ter me dado sabedoria para que eu fizesse as melhores escolhas. A todas as mulheres fortes e inspiradoras próximas a mim. Entre elas: minha mãe, uma mulher incrível que sempre me moveu com sua determinação. -

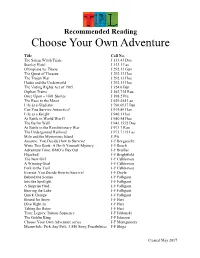

Choose Your Own Adventure

Recommended Reading Choose Your Own Adventure Title Call No. The Salem Witch Trials J 133.43 Doe Stanley Hotel J 133.1 Las Olympians vs. Titans J 292.13 Gun The Quest of Theseus J 292.13 Hoe The Trojan War J 292.13 Hoe Hades and the Underworld J 292.13 Hoe The Voting Rights Act of 1965 J 324.6 Bur Orphan Trains J 362.734 Rau Once Upon – 1001 Stories J 398.2 Pra The Race to the Moon J 629.454 Las Life as a Gladiator J 796.0937 Bur Can You Survive Antarctica? J 919.89 Han Life as a Knight J 940.1 Han At Battle in World War II J 940.54 Doe The Berlin Wall J 943.1552 Doe At Battle in the Revolutionary War J 973.7 Rau The Underground Railroad J 973.7115 Las Milo and the Mysterious Island E Pfi Amazon: You Decide How to Survive! J-F Borgenicht Write This Book: A Do-It Yourself Mystery J-F Bosch Adventure Time: BMO’s Day Out J-F Brallier Hijacked! J-F Brightfield The New Girl J-F Calkhoven A Winning Goal J-F Calkhoven Fork in the Trail J-F Calkhoven Everest: You Decide How to Survive! J-F Doyle Behind the Scenes J-F Falligant Into the Spotlight J-F Falligant A Surprise Find J-F Falligant Braving the Lake J-F Falligant Quick Change J-F Falligant Bound for Snow J-F Hart Dive Right In J-F Hart Taking the Reins J-F Hart Tron: Legacy: Initiate Sequence J-F Jablonski The Goblin King J-F Johnson Choose Your Own Adventure series J-F Montgomery Meanwhile: Pick Any Path. -

Item # Silent Auction 100 "Stand Tall Little One" Blanket & Book Gift Set

Item # Silent Auction 100 "Stand Tall Little One" Blanket & Book Gift Set 101 Automoblox Minis, HR5 Scorch & SC1 Chaos 2-Pack Cars 102 Barnyard Fun Gift Set 103 Blokko LED Powered Building System 3-in-1 Light FX Copters, 49 pieces 104 Blue Paw Patrol Duffle Bag 105 Busy Bin Toddler Activity Basket 106 Calico Critters Country Doctor Gift Set + Calico Critters Mango Monkey Family 107 Calico Critters DressUp Duo Set 108 Caterpillar (CAT) Tough Tracks Dump Truck 109 Child's Knitted White Scarf & Hat, Snowman Design 110 Creative Kids Posh Pet Bowls 111 Discovery Bubble Maker Ultimate Flurry 112 Fisher Price TV Radio, Vintage Design 113 Glowing Science Lab Activity Kit + Earth Science Bingo Game for Kids 114 Green Toys Airplane + Green Toys Stacker 115 Green Toys Construction SET, Scooper & Dumper 116 Green Toys Sandwich Shop, 17Piece Play Set 117 Hasbro NERF Avengers Set, Captain America & Iron Man 118 Here Comes the Fire Truck! Gift Set 119 Knitted Children's Hat, Butterfly 120 Knitted Children's Hat, Dog 121 Knitted Children's Hat, Kitten 122 Knitted Children's Hat, Llama 123 LaserX Long-Range Blaster with Receiver Vest (x2) 124 LEGO Adventure Time Building Kit, 495 Pieces 125 LEGO Arctic Scout Truck, 322 pieces 126 LEGO City Police Mobile Command Center, 364 Pieces 127 LEGO Classic Bricks and Gears, 244 Pieces 128 LEGO Classic World Fun, 295 Pieces 129 LEGO Friends Snow Resort Ice Rink, 307 pieces 130 LEGO Minecraft The Polar Igloo, 278 pieces 131 LEGO Unikingdom Creative Brick Box, 433 pieces 132 LEGO UniKitty 3-Pack including Party Time, -

Universidade Estadual Da Paraíba Campus Iii Centro De Humanidades Departamento De História Curso De História

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DA PARAÍBA CAMPUS III CENTRO DE HUMANIDADES DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTÓRIA CURSO DE HISTÓRIA ÔNISSON BATISTA BESERRA A REPRESENTATIVIDADE SEXUAL NO CARTOON “STEVEN UNIVERSE” GUARABIRA 2019 ÔNISSON BATISTA BESERRA A REPRESENTATIVIDADE SEXUAL NO CARTOON “STEVEN UNIVERSE” Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Artigo) apresentado à Coordenação do Curso de História da Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Licenciado em História. Área de concentração: Gênero. Orientador: Prof.ª Dr.ª Susel Oliveira de Rosa. GUARABIRA 2019 É expressamente proibido a comercialização deste documento, tanto na forma impressa como eletrônica. Sua reprodução total ou parcial é permitida exclusivamente para fins acadêmicos e científicos, desde que na reprodução figure a identificação do autor, título, instituição e ano do trabalho. B554r Beserra, Onisson Batista. A representatividade sexual no cartoon "Steven Universe" [manuscrito] / Onisson Batista Beserra. - 2019. 26 p. : il. colorido. Digitado. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Graduação em História) - Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Centro de Humanidades , 2019. "Orientação : Prof. Dr. Susel Oliveira de Rosa , Departamento de História - CEDUC." 1. Steven Universe. 2. Representatividade. 3. Sexualidade. I. Título 21. ed. CDD 305.21 Elaborada por Andreza N. F. Serafim - CRB - 15/661 BSC3/UEPB À minha mãe e meu pai, pela dedicação, companheirismo, amizade, amor e zelo, DEDICO. I learned compassion from being discriminated against. Everything bad that's ever happened to me has taught me compassion. Ellen DeGeneres Eu aprendi o que era compaixão por ser discriminada. Tudo de ruim que já me aconteceu ensinou- me sobre compaixão. (tradução nossa) LISTA DE ILUSTRAÇÕES Figura 1 – Sapphire beija Ruby.......................................................................... -

National Journalism Awards

George Pennacchio Carol Burnett Michael Connelly The Luminary The Legend Award The Distinguished Award Storyteller Award 2018 ELEVENTH ANNUAL Jonathan Gold The Impact Award NATIONAL ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB CBS IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY CAROL BURNETT. YOUR GROUNDBREAKING CAREER, AND YOUR INIMITABLE HUMOR, TALENT AND VERSATILITY, HAVE ENTERTAINED GENERATIONS. YOU ARE AN AMERICAN ICON. ©2018 CBS Corporation Burnett2.indd 1 11/27/18 2:08 PM 11TH ANNUAL National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards Los Angeles Press Club Awards for Editorial Excellence in A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 2017 and 2018, Honorary Awards for 2018 6464 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 870 Los Angeles, California 90028 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (310) 464-3577 E-mail: [email protected] Carper Du;mage Website: www.lapressclub.org Marie Astrid Gonzalez Beowulf Sheehan Photography Beowulf PRESS CLUB OFFICERS PRESIDENT: Chris Palmeri, Bureau Chief, Bloomberg News VICE PRESIDENT: Cher Calvin, Anchor/ Reporter, KTLA, Los Angeles TREASURER: Doug Kriegel, The Impact Award The Luminary The TV Reporter For Journalism that Award Distinguished SECRETARY: Adam J. Rose, Senior Editorial Makes a Difference For Career Storyteller Producer, CBS Interactive JONATHAN Achievement Award EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus GOLD International Journalist GEORGE For Excellence in Introduced by PENNACCHIO Storytelling Outside of BOARD MEMBERS Peter Meehan Introduced by Journalism Joe Bell Bruno, Freelance Journalist Jeff Ross MICHAEL Gerri Shaftel Constant, CBS CONNELLY CBS Deepa Fernandes, Public Radio International Introduced by Mariel Garza, Los Angeles Times Titus Welliver Peggy Holter, Independent TV Producer Antonio Martin, EFE The Legend Award Claudia Oberst, International Journalist Lisa Richwine, Reuters For Lifetime Achievement and IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR FRIEND, THE EXTRAORDINARY Ina von Ber, US Press Agency Contributions to Society CAROL BURNETT.