Weaving Relationality Into Métis Material Culture Repatriation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of the Corporate Plan 2009-2010 to 2013-2014 OPERATING and CAPITAL BUDGETS for 2009-2010 Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada

SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATE PLAN 2009-2010 TO 2013-2014 OPERATING AND CAPITAL BUDGETS FOR 2009-2010 ALLIANCE OF NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUMS OF CANADA The Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada is dedicated to the preservation and understanding of Canada’s natural heritage. By working in partnership, the Alliance is able to provide enhanced public programming with national reach, contribute to informed decision making in areas of public policy, and enhance collections planning and development to facilitate public and scientific access to collections information. MEMBERS: Canadian Museum of Nature • Montréal’s Nature Museums New Brunswick Museum • Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre • Royal Alberta Museum Royal British Columbia Museum • Royal Ontario Museum • Royal Saskatchewan Museum Royal Tyrrell Museum • The Manitoba Museum • The Rooms, Provincial Museum Division Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre CANADIAN MUSEUM OF NATURE BOARD OF TRUSTEES CHAIR R. Kenneth Armstrong, O.M.C., Peterborough, Ontario VI C E - C H A I R Dana Hanson, M.D., Fredericton, New Brunswick MEMBERS Lise des Greniers, Granby, Quebec Martin Joanisse, Gatineau, Quebec Teresa MacNeil, O.C., Johnstown, Nova Scotia (until June 18, 2008) Melody McLeod, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories Mark Muise, Yarmouth, Nova Scotia (effective June 18, 2008) Chris Nelson, Ottawa, Ontario Erin Rankin Nash, London, Ontario Harold Robinson, Edmonton, Alberta Henry Tom, Vancouver, British Columbia Jeffrey A. Turner, Manotick, Ontario EXECUTIVE StAFF -

“Indianness” and the Fur Trade: Representations of Aboriginal People in Two Canadian Museums

“INDIANNESS” AND THE FUR TRADE: REPRESENTATIONS OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE IN TWO CANADIAN MUSEUMS BY MALLORY ALLYSON RICHARD A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History University of Manitoba / University of Winnipeg Winnipeg Copyright © 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Mallory Allyson Richard ii ABSTRACT Museum representations of Aboriginal people have a significant influence over the extent to which Aboriginal presence in and contributions to Canadian history form part of the national public memory. These representations determine, for example, Canadians‟ awareness and acknowledgment of the roles Aboriginal people played in the Canadian fur trade. As the industry expanded its reach west to the Pacific and north to the Arctic, Aboriginal people acted as allies, guides, provisioners, customers, friends and family to European and Canadian traders. The meaningful inclusion of Aboriginal experiences in and perspectives on the fur trade in museums‟ historical narratives is, however, relatively recent. Historically, representations of Aboriginal people reflected the stereotypes and assumptions of the dominant culture. These portrayals began to change as protest, debate and the creation of The Task Force on Museums and First Peoples took off in the late 1980s, leading to the recognition of the need for Aboriginal involvement in museum activities and exhibitions. This project examines whether these changes to the relationships between museums and Aboriginal people are visible in the exhibits and narratives that shape public memory. It focuses on references to the fur trade found in the Canadian Museum of Civilization‟s First Peoples Hall and Canada Hall and throughout the Manitoba Museum, using visitor studies, learning theory and an internal evaluation of the Canada Hall to determine how and what visitors learn in these settings. -

Renewinga National Treasure

RENEWINGA NATIONAL TREASURE Summary of the Corporate Plan 2005-06 to 2009-10 Capital and Operating Budget 2005-06 Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada The Alliance of Natural History Museums of Canada is dedicated to the preservation and understanding of Canada’s natural heritage. By working in partnership, the Alliance is able to provide enhanced public programming with national reach, contribute to informed decision making in areas of public policy, and enhance collections planning and development to facilitate public and scientific access to collections information. Members: • Biodôme, Insectarium, Jardin botanique • Provincial Museum of Alberta et Planétarium de Montréal • Provincial Museum of Newfoundland • Canadian Museum of Nature and Labrador • Manitoba Museum • Royal British Columbia Museum • New Brunswick Museum • Royal Saskatchewan Museum • Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History • Royal Tyrrell Museum • Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre • Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre Canadian Museum of Nature BOARD OF TRUSTEES VICE-CHAIR (AND ACTING CHAIR) Louise Beaubien Lepage, Montreal, Quebec MEMBERS R. Kenneth Armstrong, O.M.C., Peterborough, Ontario Patricia Stanley Beck, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Johanne Bouchard, Longueuil, Quebec Charmaine Crooks, North Vancouver, British Columbia Jane Dragon, Fort Smith, Northwest Territories Garry Parenteau, Fishing Lake, Alberta Roy H. Piovesana, Thunder Bay, Ontario EXECUTIVE STAFF Joanne DiCosimo, President and Chief Executive Officer Maureen Dougan, Vice-President, Corporate Services and Chief Operating Officer CANADIAN MUSEUM OF NATURE Table of Contents CORPORATE OVERVIEW Mandate and Vision . 2 Corporate Profile . 7 Financial Resources . 8 SITUATION ANALYSIS External Environment . 9 Internal Analysis . 11 OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES – 2004-05 . 13 OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES FOR 2005-06 TO 2009-2010 . -

Complete Financial Statements 2018-2019

Non-Consolidated Financial Statements of THE MANITOBA MUSEUM Year ended March 31, 2019 KPMG LLP Telephone (204) 957-1770 One Lombard Place Fax (204) 957-0808 Suite 2000 www.kpmg.ca Winnipeg MB R3B 0X3 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT To the Members of The Manitoba Museum Opinion We have audited the non-consolidated financial statements of The Manitoba Museum (the Entity), which comprise the non-consolidated statement of financial position as at March 31, 2019, the non- consolidated statements of operations and changes in fund balances and cash flows for the year then ended, and notes to the non-consolidated financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies (hereinafter referred to as the “financial statements”). In our opinion, the accompanying financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the non- consolidated financial position of the Entity as at March 31, 2019, and its non-consolidated results of operations and its non-consolidated cash flows for the year then ended in accordance with Canadian accounting standards for not-for-profit organizations. Basis for Opinion We conducted our audit in accordance with Canadian generally accepted auditing standards. Our responsibilities under those standards are further described in the “Auditors’ Responsibilities for the Audit of the Financial Statements” section of our auditors’ report. We are independent of the Entity in accordance with the ethical requirements that are relevant to our audit of the financial statements in Canada and we have fulfilled our other ethical responsibilities in accordance with these requirements. We believe that the audit evidence we have obtained is sufficient and appropriate to provide a basis for our opinion. -

Racial and Gender Shifting in Gregory Scofield's Under Rough My Veins

Racial and Gender Shifting in Gregory Scoeld’s under rough My Veins (1999) Eszter Szenczi In my paper, I explore the literary strategy of decolonizing racial and gender binaries alike through the memoir of one of Canada’s best-known Metis Two- Spirit authors, Gregory Sco!eld, whose work interrupted the previously ruling national collective myth that excluded the voices of those Aboriginal people who have become categorised as second class citizens since Colonization. He has produced a number of books of poetry and plays that have drawn on Cree story- telling traditions. His memoir under rough My Veins (1999) is resonant for those who have struggled to trace their roots or wrestled with their identity. By recalling his childhood di"culties as a Metis individual with an alternative gender, he has challenged the Canadian literary presentation of Metis and Two-Spirited people and has created a book of healing for both himself and also for other Metis people struggling with prejudice. In order to provide a historical, cultural, and theoretical background, I will start my analysis of Sco!eld’s memoir by giving a brief recapitulation of the problematics of racial and gender identities, overlapping identities and life-writing as a means of healing. #e history of Canada is largely the history of the colonization of the Indigenous people. Out of the Colonization process grew the Metis, a special segment of the Aboriginal population having European and Indigenous ancestry. #e earliest mixed marriages can be traced back to the !rst years of contact but the metis born out of these relationships did not yet have a political sense of distinctiveness (Macdougall 424). -

Literary Language Revitalization: Nêhiyawêwin, Indigenous Poetics, and Indigenous Languages in Canada

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-8-2017 10:30 AM Literary Language Revitalization: nêhiyawêwin, Indigenous Poetics, and Indigenous Languages in Canada Emily L. Kring The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Wakeham, Pauline The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Emily L. Kring 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons, Poetry Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Kring, Emily L., "Literary Language Revitalization: nêhiyawêwin, Indigenous Poetics, and Indigenous Languages in Canada" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5170. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5170 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation reads the spaces of connection, overlap, and distinction between nêhiyaw (Cree) poetics and the concepts of revitalization, repatriation, and resurgence that have risen to prominence in Indigenous studies. Engaging revitalization, resurgence, and repatriation alongside the creative work of nêhiyaw and Métis writers (Louise Bernice Halfe, -

Annual Report 2017-2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017–2018 LEGACIES OF CONFEDERATION EXHIBITION EXPLORED CANADA 150 WITH A NEW LENS N THE OCCASION OF THE 150th ANNIVERSARY OF CONFEDERATION, the Manitoba OMuseum created a year-long exhibition that explored how Confederation has aff ected Manitoba since 1867. Legacies of Confederation: A New Look at Manitoba History featured some of the Museum’s fi nest artifacts and specimens, as well as some loaned items. The topics of resistance, Treaty making, subjugation, All seven Museum Curators representing both and resurgence experienced by the Indigenous natural and human history worked collaboratively peoples of Manitoba were explored in relation to on this exhibition. The development of Legacies of Confederation. Mass immigration to the province Confederation also functioned as a pilot exhibition after the Treaties were signed resulted in massive for the Bringing Our Stories Forward Capital political and economic changes and Manitoba has Renewal Project. Many of the themes, artifacts and been a province of immigration and diversity ever specimens found in Legacies of Confederation are since. Agricultural settlement in southern Manitoba being considered for the renewed galleries as part after Confederation transformed the ecology of of the Bringing Our Stories Forward Project. the region. The loss of wildlife and prairie landscapes in Manitoba has resulted in ongoing conservation eff orts led by the federal and provincial governments since the 1910s. FRONT COVER: Louis Riel, the Wandering Statesman Louis Riel was a leading fi gure in the Provisional Government of 1870, which took control of Manitoba and led negotiations with Canada concerning entrance into Confederation. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada /C-006688d 1867 Confederation Medal The symbolism of this medal indicates that the relationship between the Dominion of Canada and the British Empire was based on resource exploitation. -

Indigenous Book List Fiction: TITLE

Indigenous book list Fiction: TITLE: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian AUTHOR: Sherman Alexie ISBN13: 978-0316013697 PAGES: 288 GENRE: Fiction/Humour by Native American author SYNOPSIS: Based on the author's own experiences, and coupled with poignant drawings by Ellen Forney that reflect the character's art, this semi-autobiography chronicles the contemporary adolescence of one Native American boy as he attempts to break away from the life he was destined to live. Heartbreaking, funny, and beautifully written. TITLE: Song of Batoche AUTHOR: Maia Caron ISBN13: 978-1553804994 PAGES: 372 GENRE: Native American Fiction SYNOPSIS: Louis Riel arrives at Batoche in 1884 to help the Métis fight for their lands and discovers that the rebellious outsider Josette Lavoie is a granddaughter of the famous chief Big Bear, whom he needs as an ally. But Josette learns of Riel's hidden agenda - to establish a separate state with his new church at its head - and refuses to help him. Only when the great Gabriel Dumont promises her that he will not let Riel fail does she agree to join the cause. In this raw wilderness on the brink of change, the lives of seven unforgettable characters converge, each one with secrets: Louis Riel and his tortured wife Marguerite; a duplicitous Catholic priest; Gabriel Dumont and his dying wife Madeleine; a Hudson's Bay Company spy; and the enigmatic Josette Lavoie. As the Dominion Army marches on Batoche, Josette and Gabriel must manage Riel's escalating religious fanaticism and a growing attraction to each other. Song of Batoche is a timeless story that traces the borderlines of faith and reason, obsession and madness, betrayal and love. -

SAWCI Presents: Ânskohk Aboriginal Literature Festival

HOME 2014 Presenters About Ânskohk About SAWCI Membership Contact us Picture gallery Events Anskohk 2016 Anskohk 2014 Anskohk 2013 Anskohk 2012 Anskohk 2011 SAWCI presents: Ânskohk Aboriginal Literature Festival CALL FOR PROPOSALS Saskatchewan Aboriginal Writers Circle Inc (SAWCI) is presently accepting proposals and applications from organizations/vendors interested in providing services for the coordination and delivery of an Indigenous Literature Festival, as well as proactive services to engage youth and the Indigenous writing community in Saskatchewan. The location of the services is Saskatoon SK with activities province-wide. The closing date for receiving applications and proposals is noon April 14, 2017. Full application package available here. Thank you for joining us for the 2016 Ânskohk Aboriginal Literature Festival We were so pleased to see our Anskohk Literature Festival events so well attended. We hope participants went away with nuggets of insight! Our success is shared with our partner, the Saskatchewan Writers' Guild and our sponsors belief in supporting Indigenous literature in Saskatchewan. We extend our heartfelt gratitude for your generosity. Thank you! Maarsii kinanaskomtinan. To Contact SAWCI, Email: [email protected] CONTACT US We would like to thank the following partners, sponsors, and supporters: Make a Free Website with Yola. HOME 2014 Presenters About Ânskohk About SAWCI Membership Contact us Picture gallery Events Anskohk 2016 Anskohk 2014 Anskohk 2013 Anskohk 2012 Anskohk 2011 Ânskohk Aboriginal Writer's Festival Simon Ash-Moccasin Simon Ash-Moccasin resides in Regina with his daughters Maija and Sage. He is from the Little Jackfish Lake Reserve (Saulteaux First Nations) on Treaty 6 Territory in Saskatchewan. -

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke This month Pat Lowther Memorial Award Juror A.F. Moritz, news from Penn Kemp; Introducing new members Kelly Norah Drukker, Veronica Gaylie and Robin Richardson; Reviews of Sword Dance , by Veronica Gaylie, small fires , by Kelly Norah Drukker, and Distributaries , by Laura McRae; U. of Toronto Press Previews of Witness I am , by Gregory Scofield, for Muskrat Woman,” the middle part of the book, is a breathtaking epic poem that considers the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women through the re-imagining and retelling of a sacred Cree creation story ; The Girl and the Game , A History of Women's Sport in Canada ; "I wish to keep a record" Nineteenth-Century New Brunswick Women Diarists and Their World ; and Female Suicide Bombings: A Critical Gender Approach. According to Mary Ellen Csamer the other Pat Lowther Memorial Award Juror is A. F. Moritz. A.F. Moritz (Albert F. Moritz) is the author of more than 15 books of poetry; he has received the Award in Literature from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, the Relit Award (for Night Street Repairs , named the best book of poetry published in Canada in 2005), an Ingram Merrill Fellowship, and a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation. A Canadian citizen, Moritz was born in Ohio and moved to Canada in 1974. In a review of Night Street Repairs , Lorri Neilsen Glenn observed, “Moritz has a panoptical gaze, intense, compassionate, and scholarly.” He is as likely to examine contemporary situations as classical references; critics have noted his adept handling of the poetic line and the muscularity of his language. -

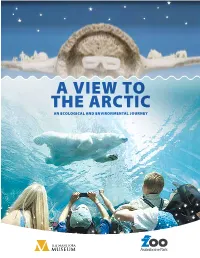

A View to the Arctic a View to the Arctic

A VIEW TO THE ARCTIC AN ECOLOGICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL JOURNEY Assiniboine Park Zoo and The Manitoba Museum are offering a unique way to learn more about Arctic and Sub-Arctic life in Manitoba! With this unique partnership, you’ll learn about polar bears, First Nations and Inuit culture. Explore sustainable resources of the Arctic, and the effects that we as humans have on the environment. Spend a full day exploring! Start your morning at Assiniboine Park Zoo, where an outdoor adventure awaits, complete with guided tour and hands-on activities which explore specific adaptations in the Zoo’s premier Arctic exhibition Journey to Churchill. Choose your favourite place for lunch and then make your way to The Manitoba Museum for a fun-filled afternoon exploring Inuit culture, water and ice. Guided programs complete with interactive activities will see you exploring the Arctic, its people and sustainable resources. PROGRAM OPTIONS: 1. Arctic Adaptations: How Will You Adapt? Examine the environment surrounding Churchill, Manitoba, and how a changing climate may affect the animals of the north at the Assiniboine Park Zoo. Through hands-on activities, students discover how seals, Arctic fox, musk ox, snowy owls and other northern animals survive temperature extremes in the Arctic habitats. The Inuit were not the first people to inhabit the Arctic, but their success, in one of the world’s harshest environments, is a testament to their ingenuity and adaptation. Through hands-on artefact studies at the Manitoba Museum, students discover how the limited resources of skin, snow, stone and bone were integral to the survival of the Inuit. -

Report Spring | Summer 2021

REPORT SPRING | SUMMER 2021 Image: © Manitoba Museum / Ian McCausland THE MUSEUM WELCOMES A NEW CEO Dorota Blumczyńska, Manitoba Museum On May 3, the Manitoba Museum Chief Executive welcomed Dorota Blumczyńska as Officer our new Chief Executive Officer. Image: Réjean Brandt Photography For the past 10 years, Ms. Blumczyńska served as Executive Director of the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba, which strives to empower newcomers’ families to integrate into the wider community. Ms. Blumczyńska has proudly called Manitoba home since she arrived in Canada as a refugee in 1989. within them. I’ve been entrusted with the profound Ms. Blumczyńska brings with her extensive responsibility of supporting a dynamic team, experience in building and sustaining community cultivating curiosity and encouraging discovery, all connections, both of which will strengthen the while building bridges beyond our walls and beyond Museum’s important role in narrating and sharing the present. It is truly humbling, ” says Blumczyńska. Manitoba’s stories. “We undertook the CEO search process knowing how important it would be to Ms. Blumczyńska takes over from Claudette Leclerc, find a candidate who embodies a passion for our who retired following a successful 23-year career at community and the things that make it special. the helm of Manitoba’s largest not-for-profit centre for Someone who loves learning and telling the stories history, nature, and science learning and experiences. of all Manitobans. Dorota is that candidate,” says Penny McMillan, Chair of the Board of Governors. “The Manitoba Museum holds a very special place in my heart and an important chapter in my story.