Criteria for the Selection of Biological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BSBI SCOTTISH KEWSIETTER Lumber 2 Summer 1980

B.S.B. I. SCOTTISH NEWSLETTER BSBI SCOTTISH KEWSIETTER lumber 2 Summer 1980 COOTEOTS Editorial 2 Woodsia ilvensis in the Itoffat area 2 Ulex gallii in the far north of Scotland - E.R.Bullard 5 Cirsium wankelii in Argyll, v.c.98 - A.G*Kenneth 6 Discovery of Schoenus ferrugineous as a native British plant - R.A.H. Smith 7 Rosa arvensis in Scotland - O.M. Stewart 7 The year of the Dandelion - G.H. Ballantyne 8 •The Flora of Kintyre1. Review - P. Macpherson 9 Liaison between the BSBI and Nature Conservancy Council 10 HCC Assistant Regional Officers 10 Calamagrostis - 0«M. Stewart 13 Spiraea salicifolia group - A.J, Silverside 13 % Chairman's Letter 14 Flora of Uig (Lewis) 15 Cover Illustration - Woodsia ilvensis by Olga M. Stewart 1 EDITORIAL staff, who is the author of a recent report on the subjecto * We hope that this, the second number of the newsletter, meets with the approval of our readers, but its success The report is divided into four parts - Geographical can only be judged by our receiving your comments and distribution? Ecological aspects? Past and Present Status constructive criticism, so please let us know what you in the Moffat Hills? and Conservation in Britain. The think of our efforts® world, European and British distribution is discussed in Our cover illustration, for which we are once again general terms, with appropriate maps. These show W. indebted to Mrs Olga Stewart, has been chosen as an ilvensis to be a fern of the i'orth Temperate zone, con fined to the Arctic and mountainous regions, extending as accompaniment to the item on Woodsia ilvensis. -

Identification of White Campion (Silene Latifolia) Guaiacol O-Methyltransferase Involved in the Biosynthesis of Veratrole, a Key Volatile for Pollinator Attraction

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Identification of white campion (Silene latifolia) guaiacol O-methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of veratrole, a key volatile for pollinator attraction Gupta, Alok K ; Akhtar, Tariq A ; Widmer, Alex ; Pichersky, Eran ; Schiestl, Florian P Abstract: BACKGROUND: Silene latifolia and its pollinator, the noctuid moth Hadena bicruris, repre- sent an open nursery pollination system wherein floral volatiles, especially veratrole (1, 2-dimethoxybenzene), lilac aldehydes, and phenylacetaldehyde are of key importance for floral signaling. Despite the important role of floral scent in ensuring reproductive success in S. latifolia, the molecular basis of scent biosyn- thesis in this species has not yet been investigated. RESULTS: We isolated two full-length cDNAs from S. latifolia that show similarity to rose orcinol O-methyltransferase. Biochemical analysis showed that both S. latifolia guaiacol O-methyltransferase1 (SlGOMT1) S. latifolia guaiacol O-methyltransferase2 (SlGOMT2) encode proteins that catalyze the methylation of guaiacol to form veratrole. A large Km value difference between SlGOMT1 ( 10 M) and SlGOMT2 ( 501 M) resulted that SlGOMT1 is31-fold more catalytically efficient than SlGOMT2. qRT-PCR expression analysis showed that theSlGOMT genes are specifically expressed in flowers and male S. latifolia flowers had 3- to 4-folds higher levelof GOMT gene transcripts than female flower tissues. Two related cDNAs, S. dioica O-methyltransferase1 (SdOMT1) and S. dioica O-methyltransferase2 (SdOMT2), were also obtained from the sister species Silene dioica, but the proteins they encode did not methylate guaiacol, consistent with the lack of ver- atrole emission in the flowers of this species. -

Oberholzeria (Fabaceae Subfam. Faboideae), a New Monotypic Legume Genus from Namibia

RESEARCH ARTICLE Oberholzeria (Fabaceae subfam. Faboideae), a New Monotypic Legume Genus from Namibia Wessel Swanepoel1,2*, M. Marianne le Roux3¤, Martin F. Wojciechowski4, Abraham E. van Wyk2 1 Independent Researcher, Windhoek, Namibia, 2 H. G. W. J. Schweickerdt Herbarium, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 3 Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4 School of Life Sciences, Arizona a11111 State University, Tempe, Arizona, United States of America ¤ Current address: South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, South Africa * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Oberholzeria etendekaensis, a succulent biennial or short-lived perennial shrublet is de- Citation: Swanepoel W, le Roux MM, Wojciechowski scribed as a new species, and a new monotypic genus. Discovered in 2012, it is a rare spe- MF, van Wyk AE (2015) Oberholzeria (Fabaceae subfam. Faboideae), a New Monotypic Legume cies known only from a single locality in the Kaokoveld Centre of Plant Endemism, north- Genus from Namibia. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0122080. western Namibia. Phylogenetic analyses of molecular sequence data from the plastid matK doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122080 gene resolves Oberholzeria as the sister group to the Genisteae clade while data from the Academic Editor: Maharaj K Pandit, University of nuclear rDNA ITS region showed that it is sister to a clade comprising both the Crotalarieae Delhi, INDIA and Genisteae clades. Morphological characters diagnostic of the new genus include: 1) Received: October 3, 2014 succulent stems with woody remains; 2) pinnately trifoliolate, fleshy leaves; 3) monadel- Accepted: February 2, 2015 phous stamens in a sheath that is fused above; 4) dimorphic anthers with five long, basifixed anthers alternating with five short, dorsifixed anthers, and 5) pendent, membranous, one- Published: March 27, 2015 seeded, laterally flattened, slightly inflated but indehiscent fruits. -

Biodiversity Action Plan 2011-2014

Falkirk Area Biodiversity Action Plan 2011-2014 A NEFORA' If you would like this information in another language, Braille, LARGE PRINT or audio, please call 01324 504863. For more information about this plan and how to get involved in local action for biodiversity contact: The Biodiversity Officer, Falkirk Council, Abbotsford House, David’s Loan, Falkirk FK2 7YZ E-mail: [email protected] www.falkirk.gov.uk/biodiversity Biodiversity is the variety of life. Biodiversity includes the whole range of life - mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, plants, trees, fungi and micro-organisms. It includes both common and rare species as well as the genetic diversity within species. Biodiversity also refers to the habitats and ecosystems that support these species. Biodiversity in the Falkirk area includes familiar landscapes such as farmland, woodland, heath, rivers, and estuary, as well as being found in more obscure places such as the bark of a tree, the roof of a house and the land beneath our feet. Biodiversity plays a crucial role in our lives. A healthy and diverse natural environment is vital to our economic, social and spiritual well being, both now and in the future. The last 100 years have seen considerable declines in the numbers and health of many of our wild plants, animals and habitats as human activities place ever-increasing demands on our natural resources. We have a shared responsibility to conserve and enhance our local biodiversity for the good of current and future generations. For more information -

Sheep and Goat Grazing Effects on Three Atlantic Heathland Types Berta M

Rangeland Ecol Manage 62:119–126 | March 2009 Sheep and Goat Grazing Effects on Three Atlantic Heathland Types Berta M. Ja´uregui,1 Urcesino Garcı´a,2 Koldo Osoro,3 and Rafael Celaya1 Authors are 1Research Associates, 2Experimental Farm Manager, and 3Research Head, Animal Production Systems Department, Servicio Regional de Investigacio´n y Desarrollo Agroalimentario, Apdo. 13, 33300 Villaviciosa, Asturias, Spain Abstract Heathlands in the northwest of Spain have been traditionally used by domestic herbivores as a food resource. However, their abandonment in the past decades has promoted a high incidence of wildfires, threatening biodiversity. Sheep and goats exhibit different grazing behavior, affecting rangelands dynamics in a different way, but the botanical and structural composition may also affect such dynamics. The aim of this article was to compare the grazing effects of sheep and goats on three different heathland types: previously burned grass- or gorse (Ulex gallii Planchon)-dominated and unburned heather (Erica spp.)- dominated shrublands. Two grazing treatments (sheep or goats) were applied in each vegetation type in a factorial design with two replicates (12 experimental plots). A small fenced area was excluded from grazing in each plot (control treatment). The experiment was carried out from 2003 to 2006, and the grazing season extended from May to October–November. Plant cover, canopy height, and phytomass amount and composition were assessed in each plot. Results showed that goats controlled shrub encroachment, phytomass accumulation, and canopy height more than sheep in either burned grass– and gorse– and unburned heather–dominated shrublands. It was accompanied by a higher increase of herbaceous species under goat grazing. -

Section Elisanthe)

POPULATION GENETICS AND SPECIATION IN THE PLANT GENUS SILENE (SECTION ELISANTHE) by ANDREA LOUISE HARPER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Biosciences The University of Birmingham 2009 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with speciation and population genetics in the plant genus Silene (section Elisanthe). The introductory chapter is a literature review covering characteristics of the species studied, and the current literature on their evolutionary dynamics and population genetics. The second and third chapters cover techniques used in all experiments, such as DNA extraction, sequencing and genotyping protocols, and explain the rationale behind the initial experimental design. The fourth chapter focuses on the multi-locus analysis of autosomal gene sequences from S. latifolia and S. dioica. The relationship between the two species was investigated using various analyses such as isolation modeling and admixture analysis providing estimates of evolutionary distance and extent of historical gene flow. The maintenance of the species despite frequent hybridization at present-day hybrid zones is discussed. -

2020 Plant List 1

2020 issima Introductions Sesleria nitida Artemisia lactiflora ‘Smoke Show’ Succisella inflexa 'Frosted Pearls' Impatiens omeiana ‘Black Ice’ Thalictrum contortum Kniphofia ‘Corn Dog’ Thalictrum rochebrunianum var. grandisepalum Kniphofia ‘Dries’ Tiarella polyphylla (BO) Kniphofia ‘Takis Fingers’ Verbascum roripifolium hybrids Persicaria amplexicaulis ‘Ruby Woo’ Veronica austriaca 'Ionian Skies' Sanguisorba ‘Unicorn Tails’ Sanguisorba obtusa ‘Tickled Pink’ Stock Woody and Herbaceous Perennials, New & Returning for 2020 indexed alphabetically: Alchemilla alpina Acanthus ‘Summer Beauty’ Aletris farinosa Acanthus Hollard’s Gold’ Anemone nemorosa ‘Vestal’ Acanthus syriacus Anemone nemorosa Virescens Actaea pachypoda Anemone ranunculoides Actaea rubra leucocarpa Anemone seemannii Adenophora triphylla Berkheya purpurea Pink Flower Agastache ‘Linda’ Berkheya species (Silver Hill) Agastache ‘Serpentine’ Boehmeria spicata 'Chantilly' Ajuga incisa ‘Blue Enigma’ Callirhoe digitata Amorphophallus konjac Carex plantaginea Anemonella thalictroides ‘Cameo’ Carex scaposa Anemonella thalictroides ‘Oscar Schoaff’ Deinanthe caerulea x bifida Anemonopsis macrophylla – dark stems Dianthus superbus var. speciosus Anemonopsis macrophylla – White Flower Digitalis ferruginea Angelica gigas Disporum sessile ‘Variegatum’ Anthemis ‘Cally Cream’ Echium amoenum Anthericum ramosum Echium russicum Arisaema fargesii Echium vulgare Arisaema ringens Erigeron speciosus (KDN) Arisaema sikokianum Eriogonum annuum (KDN) Artemisia lactiflora ‘Elfenbein’ Geranium psilostemon -

How to Find Us

APARTMENT SPECIFICATION HOW TO FIND US A MODERN DEVELOPMENT A9 Ramsey OF 8 LUXURY APARTMENTS Rugby Club OVERLOOKING MOORAGH LAKE Park Rd Grove Mount Lakeside Ramsey & District Apartments Cottage Hospital H Bride A13 M Jurby Windsor Mount o Andreas o Mooragh Promenade r Sulby a Lakeside The Cronk g A3 Ramsey A9 h Premier Ramsey A3 A9 Rd Glen Auldyn L Apartments A2 a Rugby Club k Park Rd A18 Kirk Michael e Park Rd Bowring Rd A3 ISLE OF MAN A2 Grove Mount A3 Peel Injebreck Ramsey & District Laxey Windsor Rd 1 2 A18 Ramsey AFC Ballig Baldrine Cottage Hospital A1 A2 Onchan H Old River Rd Dalby Foxdale N Shore Rd Bride M Glen A5 DOUGLAS Rushen A9 A13 Jurby Windsor Mount o A3 Andreas The Northerno Mooragh Promenade A5 Port Soderick r Colby Swimminga Pool A7 The Cronk Sulby g Port A5 Ramsey h Erin A3 Premier Castletown A3 A9 Rd Glen Auldyn L A2 a Port Derby Rd Park Rd k St Mary A18 Kirk Michael Su e lby Bowring Rd Riv A3 ISLE OF MAN er A2 Poyll Dooey Rd Library/Town Hall A3 Peel Injebreck Laxey SwingWindsor BridgeRd Ballig A18 Ramsey AFC Baldrine Bircham Ave A1 A3 A2 Onchan Old River Rd Dalby Foxdale Christian St N Shore Rd Glen A5 DOUGLAS Lezayre Rd A2 Rushen RAMSEY A9 A3 A3 The Northern A5 Port Soderick Colby Ramsey Swimming Pool A7 A18 Port A5 Golf Club Erin Castletown A2 Port Derby Rd 3 4 St Mary Prince’s Rd Crossags Ln Su lby R iver Poyll Dooey Rd Library/Town Hall Swing Bridge Bircham Ave A3 INTERIOR FINISHES � LED lighting BY CAR Christian St Specification: � Hardwood oak nished doors � Oak ooring From the Airport take the A5 to Douglas How To Lezayre Rd A2 and from thereRAMSEY follow signs for Ramsey with chrome ironmongery A3 � Fitted carpets BATHROOMS A18 Mountain Road. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 15th June 2021 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 138, No. 24 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2021 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 15th JUNE 2021 Present: The President of Tynwald (Hon. S C Rodan OBE) In the Council: The Lord Bishop of Sodor and Man (The Rt Rev. P A Eagles), The Attorney General (Mr J L M Quinn QC), Mr P Greenhill, Mr R W Henderson, Mrs K A Lord-Brennan, Mrs M M Maska, Mr R J Mercer, Mrs J P Poole-Wilson and Mrs K Sharpe with Mr J D C King, Deputy Clerk of Tynwald. In the Keys: The Speaker (Hon. J P Watterson) (Rushen); The Chief Minister (Hon. -

Histoires Naturelles N°16 Histoires Naturelles N°16

Histoires Naturelles n°16 Histoires Naturelles n°16 Essai de liste des Coléoptères de France Cyrille Deliry - Avril 2011 ! - 1 - Histoires Naturelles n°16 Essai de liste des Coléoptères de France Les Coléoptères forment l"ordre de plus diversifié de la Faune avec près de 400000 espèces indiquées dans le Monde. On en compte près de 20000 en Europe et pus de 9600 en France. Classification des Coléoptères Lawrence J.F. & Newton A.F. 1995 - Families and subfamilies of Coleoptera (with selected genera, notes, references and data on family-group names) In : Biology, Phylogeny, and Classification of Coleoptera. - éd. J.Pakaluk & S.A Slipinski, Varsovie : 779-1006. Ordre Coleoptera Sous-ordre Archostemata - Fam. Ommatidae, Crowsoniellidae, Micromathidae, Cupedidae Sous-ordre Myxophaga - Fam. Lepiceridae, Torridincolidae, Hydroscaphidae, Microsporidae Sous-ordre Adephaga - Fam. Gyrinidae, Halipidae, Trachypachidae, Noteridae, Amphizoidae, Hygrobiidae, Dytiscidae, Rhysodidae, Carabidae (Carabinae, Cicindelinae, Trechinae...) Sous-ordre Polyphaga Série Staphyliniformia - Superfam. Hydrophyloidea, Staphylinoidea Série Scarabaeiformia - Fam. Lucanidae, Passalidae, Trogidae, Glaresidae, Pleocmidae, Diphyllostomatidae, Geotrupidae, Belohinidae, Ochodaeidae, Ceratocanthidae, Hybrosoridae, Glaphyridae, Scarabaridea (Scarabaeinae, Melolonthinae, Cetoniinae...) Série Elateriformia - Superfam. Scirtoidea, Dascilloidea, Buprestoidea (Buprestidae), Byrrhoidea, Elateroidea (Elateridae, Lampyridae, Cantharidae...) + Incertae sedis - Fam. Podabrocephalidae, Rhinophipidae -

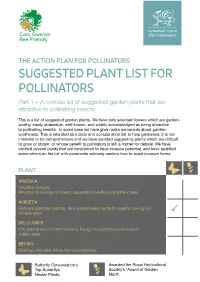

PLANT LIST for POLLINATORS Part 1 – a Concise List of Suggested Garden Plants That Are Attractive to Pollinating Insects

THE ACTION PLAN FOR POLLINATORS SUGGESTED PLANT LIST FOR POLLINATORS Part 1 – A concise list of suggested garden plants that are attractive to pollinating insects This is a list of suggested garden plants. We have only selected flowers which are garden- worthy, easily obtainable, well-known, and widely acknowledged as being attractive to pollinating insects. In some case we have given extra comments about garden- worthiness. This is intended as a clear and concise short list to help gardeners; it is not intended to be comprehensive and we have avoided suggesting plants which are difficult to grow or obtain, or whose benefit to pollinators is still a matter for debate. We have omitted several plants that are considered to have invasive potential, and have qualified some others on the list with comments advising readers how to avoid invasive forms. PLANT ANGELICA (Angelica species). Attractive to a range of insects, especially hoverflies and solitary bees. AUBRETIA (Aubrieta deltoides hybrids). An important early nectar for insects coming out of hibernation. BELLFLOWER (Campanula species and cultivars). Forage for bumblebees and some solitary bees. BETONY (Stachys officinalis). Attractive to bumblebees. Butterfly Conversation’s Awarded the Royal Horticultural Top Butterflys Society’s ‘Award of Garden Nectar Plants. Merit’. PLANT BIRD’S FOOT TREFOIL (Lotus corniculatus). Larval food plant for Common Blue, Dingy Skipper and several moths. Also an important pollen source for bumblebees. Can be grown in gravel or planted in a lawn that is mowed with blades set high during the flowering period. BOWLES’ WALLFLOWER (Erysimum Bowles Mauve). Mauve perennial wallflower, long season nectar for butterflies, moths and many bee species. -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al.