Undead and Its Undecidable Soundtrack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![La Peur [Cinéma] Sommaire La Raison De La Peur Édito](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7064/la-peur-cin%C3%A9ma-sommaire-la-raison-de-la-peur-%C3%A9dito-57064.webp)

La Peur [Cinéma] Sommaire La Raison De La Peur Édito

La Revue du Ciné-club universitaire, 2020, hors-série La peur [cinéma] Sommaire La raison de la peur Édito ..................................................................................................................... 1 Une plongée dans les archives et les images Ma vie dans l’Allemagne d’Hitler ............................................................................2 La peur de l’invasion Winston Churchill, la rhétorique de la victoire ........................................................9 Dunkerque La peur sur tous les fronts.................................................................................... 14 Peurs collectives et anticommunisme La peste rouge ....................................................................................................22 La terreur comme arme de répression La nuit des crayons..............................................................................................29 Les vertus épistémiques de YouTube Le web au service de l’histoire? ...........................................................................32 Exorciser le martyre des prisonniers de la prison de Palmyre Tadmor, de Monika Borgmann et Lokman Slim .....................................................34 Plus vampire que moi tu meurs! Nosferatu, de Murnau ..........................................................................................40 Le raid formique Them! Terreur, horreur, épouvante, massacre ....................................................... 47 Cacher la bombe La réception de The War Game ..............................................................................57 -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

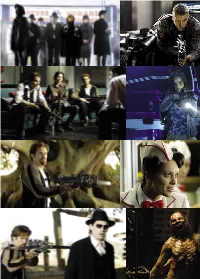

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Daybreakers and the Vampire Movie

16 • Metro Magazine 164 THERE WILL BE BLOOD Daybreakers and the Vampire Movie The enduring popularity of the vampire figure has led to some truly creative and original films as well as some downright disasters. Rjurik Davidson examines the current fascination with this genre and explores why the latest Australian offering fails to deliver despite its very promising beginning. HE VAMPIRE is the fantasy figure of the moment. Where only five years ago it was the ubiquitous boy magician Harry Potter who dominated fan- Ttasy film, now it is the vampire. Almost like a symbol of itself – transmit- ting dangerously out of control like a virus – the vampire has spread throughout popular culture, largely on the back of Stephenie Meyer’s wildly popular Twilight books and movies (Twilight [Catherine Hardwicke, 2008], New Moon [Chris Weitz, 2009]), so that there are now vampire weddings, vampire bands, a flurry of vampire novels and vampire television shows like True Blood. Recently, The Age reported that we are a nation obsessed with ‘vampires and AFL’ and that New Moon and Twilight were the most Googled movies in Australia during 2009.1 One of the great attractions of the vampire is that it can be a symbol for many things. As a symbol for the decaying aristocracy in Bram Stoker’s classic 1897 novel Dracula, the vampire has the allure of charisma and sex. Indeed, Dracula drew upon John Polidori’s 1819 portrait of Lord Byron in The Vampyre. In the symbol of the vampire, sex and death are entwined in the single act of drinking some- one’s blood. -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

Only the Dead

SCREEN AUSTRALIA PRESENTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION ONLY THE DEAD PRODUCTION NOTES Running time: 77:11 ONLY THE DEAD Directed by BILL GUTTENTAG and MICHAEL WARE Written by MICHAEL WARE Produced by PATRICK MCDONALD Produced by MICHAEL WARE Executive Producer JUSTINE A. ROSENTHAL Editor JANE MORAN Music by MICHAEL YEZERSKI Associate Producer ANDREW MACDONALD • SCREEN AUSTRALIA /PRESENTS A PENANCE FILMS / WOLFHOUND PICTURES PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SCREEN QUEENSLAND AND FOXTEL ONLY THE DEAD One Line Synopsis What happens when one of the most feared, most hated terrorists on the planet chooses you—personally—to reveal his arrival on the global stage? All in the midst of the American war in Iraq? Short Synopsis Theatrical feature documentary Only the Dead is the story of what happens when one ordinary man, an Australian journalist transplanted into the Middle East by the reverberations of 9/11, butts into history. It is a journey that courses through the deepest recesses of the Iraq war, revealing a darkness lurking in his own heart. A darkness that he never knew was there. The invasion of Iraq has ended, and the Americans are celebrating victory. The year is 2003. The international press corps revel in the Baghdad “Summer of Love”, there is barely a spare hotel room in the entire city. Reporters of all nationalities scramble for stories; of the abuses of Saddam’s fallen regime; of WMD’s, of reconstruction, of liberation. There are pool parties, and restaurant outings, and dinner-party circuits. Occasionally, Coalition forces are attacked, but always elsewhere, somewhere in the background. -

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018)

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Jigsaw, dir. Michael Spierig, Peter Spierig (Lionsgate, 2017) Finality is a concept the implications of which the horror genre seems to have blissfully disavowed when developing sequels. Studios have learned to contend with the inescapable fact that, although everything ends, a franchise’s lifespan can be prolonged by injecting a little creative adrenaline to revitalise even the most ailing brands. Narratively, it is possible to exhaust many conventional storytelling possibilities before a property changes form, such as when the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise (1984-2010) moved firmly into experimental meta-territory with Wes Craven’s New Nightmare (1994) after Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991). The term ‘final’ can also signal the onset of a crossover phase where similar properties team up for a showdown, as in Lake Placid vs Anaconda (2015) following Lake Placid: The Final Chapter (2012). Others are satisfied to ignore continuity and proceed unabated; slasher legend Jason Voorhees, for example, has twice bid farewell to audiences in the same established canon with Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984) and Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday (1993). Perhaps most amusingly guilty of having to navigate this challenge is the Final Destination franchise (2000-11). In a series built around the idea of finality, the conclusively titled The Final Destination screened in 2009, yet reneged on its promise, as Final Destination 5 (2011) arrived only two years later. Thus, following Saw: The Final Chapter (2010), comes Jigsaw (2017), the eighth instalment in the long running torture-porn series (2004-17) now explicitly named after its titular villain. -

White Zombie, I Walked with a Zombie, Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Victor Halperin, Georges A

Resisting Bodies: Power Crisis / Meaning Crisis in the Zombie Film from 1932 to Today David Roche To cite this version: David Roche. Resisting Bodies: Power Crisis / Meaning Crisis in the Zombie Film from 1932 to Today. Textes & Contextes, Université de Bourgogne, Centre Interlangues TIL, 2011, Discours autoritaires et résistances aux XXe et XXIe siècles, https://preo.u- bourgogne.fr/textesetcontextes/index.php?id=327. halshs-00682096 HAL Id: halshs-00682096 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00682096 Submitted on 23 Mar 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Resisting Bodies: Power Crisis / Meaning Crisis in the Zombie Film from 1932 to Today David Roche Maître de conférences, Centre Interlangues Texte, Image, Langage (EA 4182), Université de Bourgogne, 2 boulevard Gabriel, 21000 Dijon, mudrock [at] neuf.fr Critics have repeatedly focused on the political subtexts of the living dead films of George A. Romero, revealing, notably, how they reflect specific social concerns. In order to determine what makes the zombie movie and the figure of the zombie so productive of political readings, this article examines, first, the classic zombie movies influenced by voodoo lore, then Romero’s initial living dead trilogy (1968-1985), and finally some of the most successful films released in the 2000s. -

The Death & Life of Otto Bloom

Written and Directed by Cris Jones An Optimism Film Production Produced by Melanie Coombs, Alicia Brown and Mish Armstrong Australian Distributor Bonsai Films: Jonathan Page Duration: 84 mins Shot on Arri Alexa, Super 8, digital and analogue video, stills Format - DCP Aspect ratio – 2.39:1 Contents: Synopses: page 3 Director Bio and Filmography page 4 Directors Statement page 5 Producers Bio and Statement page 6 Lead Cast Biographies page 7 Supporting Cast Bios page 8 ABOUT the production page 9 Technical details page 12 Full Credits page 13 CONTACTS: Producer MIFF Publicity Melanie Coombs Asha Holmes +61 (0)412 304 212 + 61 (0)403 274 299 [email protected] [email protected] Australian Distributor International Sales Jonathan Page Bonsai Films +61(0)404 004 994 [email protected] www.ottobloom.com https://www.facebook.com/thedeathandlifeofottobloom/ SYNOPSES TAG LINE Who is Otto Bloom? SHORT SYNOPSIS The chronicle of the life and great love of Otto Bloom, an extraordinary man who experiences time in reverse – passing backwards through the years while remembering the future. SYNOPSIS The Death & Life of Otto Bloom chronicles the life and great love of an extraordinary man who experiences time in reverse – wandering blindly into the past, while remembering the future. The film charts Bloom's rise from scientific oddity to international superstar as he searches for love and meaning in this strange, backwards world. Over the years, he has a string of romances while challenging our preconceived notions about life, death and the nature of time. When the world proves to be not yet ready for Bloom's radical ideas, his fall from grace is as swift as it is tragic. -

Gordon Douglas (Director) Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Gordon Douglas (director) 电影 串行 (大全) They Call Me Mr. Tibbs! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/they-call-me-mr.-tibbs%21-97311285/actors Hide and Shriek https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hide-and-shriek-5752202/actors Reunion in Rhythm https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/reunion-in-rhythm-7317593/actors Spooky Hooky https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/spooky-hooky-7579123/actors Fishy Tales https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fishy-tales-5455160/actors Rogues of Sherwood Forest https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rogues-of-sherwood-forest-1133756/actors Way...Way Out https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/way...way-out-1165872/actors Glove Taps https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/glove-taps-12124555/actors Nevada Smith Tv https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/nevada-smith-tv-12126492/actors Santiago https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/santiago-12127297/actors Fort Dobbs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fort-dobbs-1412628/actors The Great Missouri Raid https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-great-missouri-raid-14906577/actors A Night of Adventure https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-night-of-adventure-15378692/actors The Sins of Rachel Cade https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-sins-of-rachel-cade-1630124/actors Gildersleeve's Bad Day https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gildersleeve%27s-bad-day-18150241/actors Gildersleeve's Ghost https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gildersleeve%27s-ghost-18150245/actors Girl Rush https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/girl-rush-18150264/actors -

Releasedate Belgium: 21 February 2018

presents releasedate Belgium: 21 February 2018 genre: thriller | horror duration: 1h39 SYNOPSIS Sarah Winchester (Helen Mirren), de excentrieke erfgename van het Winchester imperium gelooft dat ze behekst wordt door de geesten van slachtoffers van het Winchester geweer. Na het overlijden van man en kind is Sarah Winchester ervan overtuigd dat ze aan haar huis moet blijven bouwen om de geesten te weerhouden haar ook te doden. production notes, foto’s, trailer e.d. zijn terug te vinden op: https://kfd.be/seplog-restricted/ login: KFD_PRESS | password: KFD_PRESS FACTS Winchester neemt het publiek mee in een labyrinth-achtig huis waarvan gezegd wordt dat het één van de meest bezeten plaatsen ter wereld is. Vrijwel direct na de dood van Sarah werd het Winchester Mystery House opengesteld voor publiek als een toeristische attractie. Deze mysterieuze villa is te bezoeken in San Jose in de Verenigde Staten. http://www.winchestermysteryhouse.com/select-your-tour/mansion-tour/ THE LEGEND “...on the orders of a grieving widow...” Sarah Winchester (Academy Award®-winner Helen Mirren) was more than just an heiress of an enormous fortune and majority shareholder of the company that made it. She was also the architect of a macabre plan to turn an 8-room San Jose, California farmhouse into a sprawling, labyrinth of inexplicable spectral chambers... Seven stories high. 47 fireplaces, many that could never be used. 500 perplexing rooms embellished with symbols, encryptions and the 2,000 doors, trap doors, spry holes, gables, number 13 embedded everywhere. turrets, towers, porches. A maze of confusing halls. A séance room in a Witch’s Cap only Sarah was privy to. -

Copyright University Press of Colorado for Educational Use Only the Kiss of Death

Copyright University Press of Colorado For educational use only The Kiss of Death Copyright University Press of Colorado For educational use only Copyright University Press of Colorado For educational use only The Kiss of Death Contagion, Contamination, and Folklore Andrea Kitta Utah State University Press Logan Copyright University Press of Colorado For educational use only © 2019 by University Press of Colorado Published by Utah State University Press An imprint of University Press of Colorado 245 Century Circle, Suite 202 Louisville, Colorado 80027 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State Uni- versity of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper) ISBN: 978-1- 60732-926- 8 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1- 60732- 927- 5 (ebook) https://doi .org/ 10.7330/ 9781607329275 Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Names: Kitta, Andrea, 1977– author. Title: The kiss of death : contagion, contamination, and folklore / Andrea Kitta. Description: Logan : Utah State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: