Cosmopolitan Struggles in Twenty-First Century Science Fiction Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

Annual Report 2019/20

Annual Report 2019 – 2020 TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 G19 REPORT OF THE NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION for the year ended 30 June 2020 In accordance with Sections 150 to 157 of the Crown Entities Act 2004, on behalf of the New Zealand Film Commission we present the Annual Report covering the activities of the NZFC for the 12 months ended 30 June 2020. Kerry Prendergast David Wright CHAIR BOARD MEMBER Image: Daniel Cover Image: Bellbird TE TUMU WHAKAATA TAONGA | NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION Annual Report – 2019/20 1 NEW ZEALAND FILM COMMISSION ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION COVID-19 Our Year in Review ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 The screen industry faced unprecedented disruption in 2020 as a result of COVID-19. At the time the country moved to Alert Level 4, 47 New Zealand screen productions were in various stages Chair’s Introduction •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 6 of production: some were near completion and already scheduled for theatrical release, some in post-production, many in production itself and several with offers of finance gearing up for CEO Report •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 pre-production. Work on these projects was largely suspended during the lockdown. There were also thousands of New Zealand crew working on international productions who found themselves NZFC Objectives/Medium Term Goals •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 without work while waiting for production to recommence. NZFC's Performance Framework ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 8 COVID-19 also significantly impacted the domestic box office with cinema closures during Levels Vision, Values and Goals ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 9 3 and 4 disrupting the release schedule and curtailing the length of time several local features Activate high impact, authentic and culturally significant Screen Stories ••••••••••••• 11 played in cinemas. -

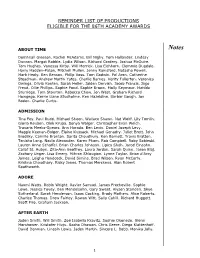

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Yahoo! Movies: Brown Sugar

TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX LINE-UP Date Titre Genre Réalisateur Cast 2019 Matt Bettinelli-Olpin Samara Weaving, Andie MacDowell, Mark O'Brien, Adam 28-août-19 WEDDING NIGHTMARE Horreur Tyler Gillett Brody Thriller Brad Pitt, Tommy Lee Jones, Donald Sutherland, 2-oct.-19 AD ASTRA James Gray Science Fiction Ruth Negga 23-oct.-19 TERMINATOR : DARK FATE Science-Fiction Tim Miller Linda Hamilton, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Gabriel Luna Comédie 30-oct.-19 STUBER Michael Dowse Dave Bautista, Kumail Nanjiani Action LE MANS 66 Action, 13-nov.-19 James Mangold Matt Damon, Christian Bale (FORD V FERRARI) Biographie 27-nov.-19 THE WOMAN IN THE WINDOW Drame/ Thriller Joe Wright Amy Adams, Julianne Moore, Wyatt Russell, Gary Oldman 4-déc.-19 THE ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN Drame Simon Curtis Amanda Seyfield, Milo Ventimiglia, Gary Cole LES INCOGNITOS Nick Bruno 25-déc.-19 Animation (Spies in Disguise) & Troy Quane Date Titre Genre Réalisateur Cast 2020 8-janv.-20 UNDERWATER Action/Drame William Eubank Kristen Stewart, T.J. Miller, Vincent Cassel Roman Griffin Davis, Thomasin McKenzie, Taika Waititi, Sam 22-janv.-20 JOJO RABBIT Drame Taika Waititi Rockwell, Scarlett Johansson 12-févr.-20 KING'S MAN Action/Aventure Matthew Vaughn 19-févr.-20 THE CALL OF THE WILD Aventure/Drame Chris Sanders Harrison Ford, Dan Stevens, Colin Woodell, Omar Sy Blu Hunt, Charlie Heaton, Maisie Williams,Henry Zaga, 1-avr.-20 NEW MUTANTS Action/ Aventure Josh Boone Anya Taylor-Joy 1-juil.-20 FREE GUY Action/ Aventure Shawn Levy Ryan Reynolds 22-juil.-20 BOB'S BURGER Animation 7-oct.-20 DEATH ON THE NILE Drame/Thriller Kenneth Branagh Kenneth Branagh 28-oct.-20 RON'S GONE WRONG Animation 16-déc.-20 WEST SIDE STORY Musical Steven Spielberg Ansel Elgort, Rita Moreno, Corey Stoll 2021 3-mars-21 NIMONA Animation 15-déc.-21 AVATAR 2 - 3D James Cameron 2023 20-déc.-23 AVATAR 3 - 3D James Cameron 2025 17-déc.-25 AVATAR 4 -3D James Cameron 2027 15-déc.-27 AVATAR 5 - 3D James Cameron A DATER A DATER GAMBIT Action/ Aventure Channing Tatum A DATER FOSTER Animation. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

GATTACA Written and Directed by Andrew Niccol ABOUT THE

Article on Gattaca by Mark Freeman Area of Study 1 & 2 Theme: Future worlds GATTACA Written and directed by Andrew Niccol Article by Mark Freeman ABOUT THE DIRECTOR Andrew Niccol, a screenwriter and director, was born in New Zealand and moved to England at the age of 21 to direct commercials. He has written and directed Gattaca, Simone and Lord of War as well as earning an Academy Award nomination for his screenplay for The Truman Show. OVERVIEW In recent years, scientific research has unearthed a greater understanding of our genetic make-up – the lottery that determines our appearance and physical capabilities. The means by which we inherit specific traits from our parents, our genes are like a blueprint of our future, determining our predisposition for specific talents or particular illnesses. Concurrent with this understanding of genetics have come successful attempts in cloning, and, more recently, the ethical debate over stem cell research to combat a range of physical maladies. Identification and eradication of rogue genes (those that could ultimately cause malfunction at birth or later in a person’s life) is a very real possibility with the developing exploration in genetic research. In your own DNA, you already carry the genetic code which will cause your physical development in your teens, your predisposition to weight gain in your twenties, your hair loss in your thirties, early menopause in your forties, the arthritis you develop in your fifties, your death from cancer in your seventies. It’s an imposing thought to consider the map of our histories, our futures, in terms of our genetic code. -

Daybreakers and the Vampire Movie

16 • Metro Magazine 164 THERE WILL BE BLOOD Daybreakers and the Vampire Movie The enduring popularity of the vampire figure has led to some truly creative and original films as well as some downright disasters. Rjurik Davidson examines the current fascination with this genre and explores why the latest Australian offering fails to deliver despite its very promising beginning. HE VAMPIRE is the fantasy figure of the moment. Where only five years ago it was the ubiquitous boy magician Harry Potter who dominated fan- Ttasy film, now it is the vampire. Almost like a symbol of itself – transmit- ting dangerously out of control like a virus – the vampire has spread throughout popular culture, largely on the back of Stephenie Meyer’s wildly popular Twilight books and movies (Twilight [Catherine Hardwicke, 2008], New Moon [Chris Weitz, 2009]), so that there are now vampire weddings, vampire bands, a flurry of vampire novels and vampire television shows like True Blood. Recently, The Age reported that we are a nation obsessed with ‘vampires and AFL’ and that New Moon and Twilight were the most Googled movies in Australia during 2009.1 One of the great attractions of the vampire is that it can be a symbol for many things. As a symbol for the decaying aristocracy in Bram Stoker’s classic 1897 novel Dracula, the vampire has the allure of charisma and sex. Indeed, Dracula drew upon John Polidori’s 1819 portrait of Lord Byron in The Vampyre. In the symbol of the vampire, sex and death are entwined in the single act of drinking some- one’s blood. -

Jo-Ann Macneil CV

JO-ANN MACNEIL +44 (0)7539 274156 Makeup Designer [email protected] Jo-Ann’s current project is Guillermo del Toro's feature "Nightmare Alley" and has just completed Denis Villeneuve's "Dune" as Key Make Up. Her recent films as Makeup Designer include the DC Comic feature film "Shazam" with Zachary Levi and Mark Strong. The Netflix original How It Ends with Forest Whitaker and Theo James and The Headhunter’s Calling with Gerard Butler. She has also recently completed Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 as Key Makeup in which she was nominated for A MUAHS guild award. David Ayer’s DC comic epic Suicide Squad as Makeup Head of Department. Suicide Squad won an Academy Award in 2017 for Achievement in Makeup. In 2014, Jo-Ann won a Canadian Screen Award for her work on The Mortal Instruments: City of Bones. Jo-Ann has always prided herself on an impeccable attention to detail that helps bring every one of her projects to life. Much in demand, she is based in the UK and available for work worldwide. Jo-Ann is a member of IATSE Local 873. Selected recent credits include: Director / Production company Date / Production Head of Department / Makeup Designer Feature Films Guillermo del Toro/Tyrone Productions 2020 Nightmare Alley 2019 SHAZAM David Sandberg / Jellystone Films 2018 HOW IT ENDS David Rosenthal / Netflix 2017 XXX: THE RETURN OF XANDER CAGE DJ. Caruso / Maple Cage Productions 2017 A FAMILY MAN Mark Williams/Zero Gravity Productions David Ayer / Atlas Entertainment 2016 SUICIDE SQUAD ** Academy Award for Achievement in Make Up 2017 Chris Colombus / Columbia Pictures 2014 PIXELS Paul W.S. -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

Title of Dissertation

SETTING UP CAMP: IDENTIFYING CAMP THROUGH THEME AND STRUCTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Michael T. Schuyler January, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Cornelius B. Pratt, Advisory Chair, Strategic Communication John A. Lent, Broadcasting, Telecommunications & Mass Media Paul Swann, Film & Media Arts Roberta Sloan, External Member, Theater i © Copyright 2010 by Michael T. Schuyler All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Camp scholarship remains vague. While academics don’t shy away from writing about this form, most exemplify it more than define it. Some even refuse to define it altogether, arguing that any such attempt causes more problems than it solves. So, I ask the question, can we define camp via its structure, theme and character types? After all, we can do so for most other genres, such as the slasher film, the situation comedy or even the country song; therefore, if camp relies upon identifiable character types and proliferates the same theme repeatedly, then, it exists as a narrative system. In exploring this, I find that, as a narrative system, though, camp doesn’t add to the dominant discursive system. Rather, it exists in opposition to it, for camp disseminates the theme that those outside of heteronormativity and acceptability triumph not in spite of but because of what makes them “different,” “othered” or “marginalized.” Camp takes many forms. So, to demonstrate its reliance upon a certain structure, stock character types and a specific theme, I look at the overlaps between seemingly disperate examples of this phenomenon. -

Blade Runner 2049 to Open the 46Th Festival Du Nouveau Cinéma

Press release For immediate release A special presentation of Denis Villeneuve’s BLADE RUNNER 2049 Opening film of the 46th Montreal Festival du nouveau cinéma (FNC) Montreal, September 21, 2017 – Montreal Festival du nouveau cinéma (FNC) is pleased to announce that Denis Villeneuve’s latest work, BLADE RUNNER 2049, will be presented at a special screening on October 4 at Théâtre Maisonneuve de la Place des Arts as the opening film of its 46th edition, which runs from October 4 to 15, 2017. After screening his first movies, the FNC is proud to welcome the Quebec director back to his hometown with his latest opus, his fourth American feature, and one of the most highly anticipated films of the year. BLADE RUNNER 2049 is a sequel to the acclaimed classic Blade Runner, directed by Ridley Scott in 1982. In the new film, a young blade runner's discovery of a long-buried secret leads him on a quest to track down former blade runner, Rick Deckard, who has been missing for thirty years. BLADE RUNNER 2049 features a star-studded cast, led by Ryan Gosling (Drive, La La Land) and Harrison Ford (the Star Wars saga, Indiana Jones), reprising his role as Rick Deckard. Also starring in the movie, are Ana de Armas (War Dogs), Sylvia Hoeks (Renegades), Robin Wright (House of Cards, Wonder Woman), Mackenzie Davis (The Martian), Carla Juri (Brimstone), and Lennie James (The Walking Dead), with Dave Bautista (the Guardians of the Galaxy films), and Jared Leto (Dallas Buyers Club, Suicide Squad). BLADE RUNNER 2049 was produced by Andrew A.