Military Justice a Reinforcer of Discipline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moves to Amend HF No. 752 As Follows: Delete Everything After the Enacting Clause and Insert

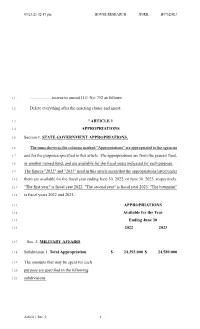

03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 752 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. STATE GOVERNMENT APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the columns marked "Appropriations" are appropriated to the agencies 1.7 and for the purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, 1.8 or another named fund, and are available for the fiscal years indicated for each purpose. 1.9 The figures "2022" and "2023" used in this article mean that the appropriations listed under 1.10 them are available for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2022, or June 30, 2023, respectively. 1.11 "The first year" is fiscal year 2022. "The second year" is fiscal year 2023. "The biennium" 1.12 is fiscal years 2022 and 2023. 1.13 APPROPRIATIONS 1.14 Available for the Year 1.15 Ending June 30 1.16 2022 2023 1.17 Sec. 2. MILITARY AFFAIRS 1.18 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 24,393,000 $ 24,589,000 1.19 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.20 purpose are specified in the following 1.21 subdivisions. Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 03/23/21 02:45 pm HOUSE RESEARCH JD/RK H0752DE3 2.1 Subd. 2. Maintenance of Training Facilities 9,772,000 9,772,000 2.2 Subd. 3. General Support 3,507,000 3,633,000 2.3 Subd. 4. Enlistment Incentives 11,114,000 11,114,000 2.4 The appropriations in this subdivision are 2.5 available until June 30, 2025, except that any 2.6 unspent amounts allocated to a program 2.7 otherwise supported by this appropriation are 2.8 canceled to the general fund upon receipt of 2.9 federal funds in the same amount to support 2.10 administration of that program. 2.11 If the amount for fiscal year 2022 is 2.12 insufficient, the amount for 2023 is available 2.13 in fiscal year 2022. -

Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?

Nebraska Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 8 1955 Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness? James W. Hewitt University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James W. Hewitt, Constitutional Law—Uniform Code of Military Justice—General Article Void for Vagueness?, 34 Neb. L. Rev. 518 (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol34/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 518 NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW CONSTITUTIONAL LAW-UNIFORM CODE OF MILITARY JUSTICE-GENERAL ARTICLE VOID FOR VAGUENESS.? Much has been said or written about the rights of servicemen under the new Uniform Code of Military Justice,1 which is the source of American written military law. Some of the major criticisms of military law have been that it is too harsh, too vague, and too careless of the right to due process of law. A large por tion of this criticism has been leveled at Article 134,2 the general, catch-all article of the Code. Article 134 provides: 3~ Alabama. Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, l\Iaine, l\Iaryland, l\Iasschusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Vermont. South Carolina has the privilege by case decision. See note 4 supra. 1 64 Stat. 107 <1950l, 50 U.S.C. §§ 551-736 (1952). -

Legal Advisers in Armed Forces

ADVISORY SERVICE ON INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW ____________________________________ Legal advisers in armed forces By ratifying the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols of 1977, a State commits itself to respecting and ensuring respect for these international legal instruments in all circumstances. Knowledge of the law is an essential precondition for its proper application. The aim of requiring legal advisers in the armed forces, as stipulated in Article. 82 of Additional Protocol I, is to improve knowledge of – and hence compliance with – international humanitarian law. As the conduct of hostilities was becoming increasingly complex, both legally and technically, the States considered it appropriate when negotiating Additional Protocol I to provide military commanders with legal advisers to help them apply and teach international humanitarian law. An obligation for States and for provisions of international humanitarian law if they are to parties to conflict humanitarian law as widely as advise military commanders possible, in particular by including effectively. “The High Contracting Parties at all the study of this branch of law in times, and the Parties to the conflict their military training programmes. This obligation is analogous to that in time of armed conflict, shall contained in Article 6 of the same ensure that legal advisers are protocol (Qualified persons), under available, when necessary, to The role of the legal adviser which the States Parties must advise military commanders at the endeavour to train qualified appropriate level on the application Article 82 gives a flexible definition personnel to facilitate the application of the Conventions and this Protocol of the legal adviser’s role, while still of the Conventions and of Additional and on the appropriate instruction to laying down certain rules. -

Gentlemen Under Fire: the U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 26 Issue 1 Article 1 June 2008 Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming Elizabeth L. Hillman Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Elizabeth L. Hillman, Gentlemen under Fire: The U.S. Military and Conduct Unbecoming, 26(1) LAW & INEQ. 1 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol26/iss1/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Gentlemen Under Fire: The U.S. Military and "Conduct Unbecoming" Elizabeth L. Hillmant Introduction ..................................................................................1 I. Creating an Officer Class ..................................................10 A. "A Scandalous and Infamous" Manner ...................... 11 B. The "Military Art" and American Gentility .............. 12 C. Continental Army Prosecutions .................................15 II. Building a Profession .........................................................17 A. Colonel Winthrop's Definition ...................................18 B. "A Stable Fraternity" ................................................. 19 C. Old Army Prosecutions ..............................................25 III. Defending a Standing Army ..............................................27 A. "As a Court-Martial May Direct". ............................. 27 B. Democratization and its Discontents ........................ 33 C. Cold War Prosecutions ..............................................36 -

Law of War Workshop Deskbook

INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL, U.S. ARMY CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA LAW OF WAR WORKSHOP DESKBOOK CDR Brian J. Bill, JAGC, USN Editor Contributing Authors CDR Brian J. Bill, JAGC, USN MAJ Geoffrey S. Corn, JA, USA LT Patrick J. Gibbons, JAGC, USN LtCol Michael C. Jordan, USMC MAJ Michael 0. Lacey, JA, USA MAJ Shannon M. Morningstar, JA, USA MAJ Michael L. Smidt, JA, USA All of the faculty who have served with and before us and contributed to the literature in the field of the Law of War June 2000 7066 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.1 DOD 004280 ii 7067 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.2 DOD 004281 INTERNATIONAL AND OPERATIONAL LAW DEPARTMENT THE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL'S SCHOOL CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA LAW OF WAR WORKSHOP DESKBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS Major Treaties Governing Land Warfare iv List of Append ices vii History of the Law of War 1 Legal Bases for the Use of Force 13 Legal Framework of the Law of War 25 The 1949 Convention on Wounded and Sick in the Field 49 Prisoners of War and Detainees 69 Protection of Civilians During Armed Conflict 123 Means and Methods of Warfare 149 War Crimes and Command Responsibility 183 The Law of War & Operations Other Than War 219 The Law of War: Methods of Instruction 255 iii 7068 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.3 DOD 004282 iv 7069 ACLU-RDI 1096 p.4 DOD 004283 MAJOR TREATIES GOVERNING LAND WARFARE Abbreviated Name Full Name GWS/lst GC Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, 12 August 1949, DA Pam 27-1. -

Volume 4 Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2015

TM VOLUME 4 ISSUE 1 FALL/WINTER 2015 National Security Law Journal George Mason University School of Law 3301 Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22201 www.nslj.org © 2015 National Security Law Journal. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Publication Data (Serial) National Security Law Journal. Arlington, Va. : National Security Law Journal, 2013- K14 .N18 ISSN: 2373-8464 Variant title: NSLJ National security—Law and legislation—Periodicals LC control no. 2014202997 (http://lccn.loc.gov/2014202997) Past issues available in print at the Law Library Reading Room of the Library of Congress (Madison, LM201). VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 (FALL/WINTER 2015) ISBN-13: 978-1523203987 ISBN-10: 1523203986 ARTICLES PLANNING FOR CHANGE: BUILDING A FRAMEWORK TO PREDICT FUTURE CHANGES TO THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE ACT Patrick Walsh QUANTUM LAWMAKING: HOW NATIONAL SECURITY LAW HAPPENS WHEN WE’RE NOT LOOKING Jesse Medlong COMMENTS TERROR IN MEXICO: WHY DESIGNATING MEXICAN CARTELS AS TERRORIST ORGANIZATIONS EASES PROSECUTION OF DRUG TRAFFICKERS UNDER THE NARCOTERRORISM STATUTE Stephen R. Jackson CYBERSPACE: THE 21ST-CENTURY BATTLEFIELD EXPOSING SOLDIERS, SAILORS, AIRMEN, AND MARINES TO POTENTIAL CIVIL LIABILITIES Molly Picard VOLUME 4 FALL/WINTER 2015 ISSUE 1 PUBLISHED BY GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW Cite as 4 NAT’L SEC. L.J. ___ (2015). The National Security Law Journal (“NSLJ”) is a student-edited legal periodical published twice annually at George Mason University School of Law in Arlington, Virginia. We print timely, insightful scholarship on pressing matters that further the dynamic field of national security law, including topics relating to foreign affairs, homeland security, intelligence, and national defense. Visit our website at www.nslj.org to read our issues online, purchase the print edition, submit an article, learn about our upcoming events, or sign up for our e-mail newsletter. -

Pub. L. 108–136, Div. A, Title V, §509(A)

§ 777a TITLE 10—ARMED FORCES Page 384 Oct. 5, 1999, 113 Stat. 590; Pub. L. 108–136, div. A, for a period of up to 14 days before assuming the title V, § 509(a), Nov. 24, 2003, 117 Stat. 1458; Pub. duties of a position for which the higher grade is L. 108–375, div. A, title V, § 503, Oct. 28, 2004, 118 authorized. An officer who is so authorized to Stat. 1875; Pub. L. 109–163, div. A, title V, wear the insignia of a higher grade is said to be §§ 503(c), 504, Jan. 6, 2006, 119 Stat. 3226; Pub. L. ‘‘frocked’’ to that grade. 111–383, div. A, title V, § 505(b), Jan. 7, 2011, 124 (b) RESTRICTIONS.—An officer may not be au- Stat. 4210.) thorized to wear the insignia for a grade as de- scribed in subsection (a) unless— AMENDMENTS (1) the Senate has given its advice and con- 2011—Subsec. (b)(3)(B). Pub. L. 111–383 struck out sent to the appointment of the officer to that ‘‘and a period of 30 days has elapsed after the date of grade; the notification’’ after ‘‘grade’’. 2006—Subsec. (a). Pub. L. 109–163, § 503(c), inserted ‘‘in (2) the officer has received orders to serve in a grade below the grade of major general or, in the case a position outside the military department of of the Navy, rear admiral,’’ after ‘‘An officer’’ in first that officer for which that grade is authorized; sentence. (3) the Secretary of Defense (or a civilian of- Subsec. (d)(1). -

My Lai Massacre 1 My Lai Massacre

My Lai Massacre 1 My Lai Massacre Coordinates: 15°10′42″N 108°52′10″E [1] My Lai Massacre Thảm sát Mỹ Lai Location Son My village, Son Tinh District of South Vietnam Date March 16, 1968 Target My Lai 4 and My Khe 4 hamlets Attack type Massacre Deaths 347 according to the U.S Army (not including My Khe killings), others estimate more than 400 killed and injuries are unknown, Vietnamese government lists 504 killed in total from both My Lai and My Khe Perpetrators Task force from the United States Army Americal Division 2LT. William Calley (convicted and then released by President Nixon to serve house arrest for two years) The My Lai Massacre (Vietnamese: thảm sát Mỹ Lai [tʰɐ̃ːm ʂɐ̌ːt mǐˀ lɐːj], [mǐˀlɐːj] ( listen); /ˌmiːˈlaɪ/, /ˌmiːˈleɪ/, or /ˌmaɪˈlaɪ/)[2] was the Vietnam War mass murder of between 347 and 504 unarmed civilians in South Vietnam on March 16, 1968, by United States Army soldiers of "Charlie" Company of 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the Americal Division. Victims included women, men, children, and infants. Some of the women were gang-raped and their bodies were later found to be mutilated[3] and many women were allegedly raped prior to the killings.[] While 26 U.S. soldiers were initially charged with criminal offenses for their actions at Mỹ Lai, only Second Lieutenant William Calley, a platoon leader in Charlie Company, was convicted. Found guilty of killing 22 villagers, he was originally given a life sentence, but only served three and a half years under house arrest. -

The Civilianization of Military Law

THE CIVILIANIZATION OF MILITARY LAW Edward F. Sherman* PART I I. INTRODUCTION Military law in the United States has always functioned as a system of jurisprudence independent of the civilian judiciary. It has its own body of substantive laws and procedures which has a different historical deri- vation than the civilian criminal law. The first American Articles of War, enacted by the Continental Congress in 1775,1 copied the British Arti- cles, a body of law which had evolved from the 17th century rules adopted by Gustavus Adolphus for the discipline of his army, rather than from the English common law.2 Despite subsequent alterations by Con- gress, the American military justice code still retains certain substantive and procedural aspects of the 18th century British code. Dissimilarity between military and civilian criminal law has been further encouraged by the isolation of the court-martial system. The federal courts have always been reluctant to interfere with the court-martial system, as ex- plained by the Supreme Court in 1953 in Burns v. Wilson:3 "Military law, like state law, is a jurisprudence which exists separate and apart from the law which governs in our federal judicial establishment. This Court has played no role in its development; we have exerted no super- visory power over the courts which enforce it .... As a result, the court-martial system still differs from the civilian court system in such aspects as terminology and structure, as well as procedural and sub- stantive law. The military has jealously guarded the distinctive aspects of its system of justice. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

The Imposition of Martial Law in the United States

THE IMPOSITION OF MARTIAL LAW IN THE UNITED STATES MAJOR KIRK L. DAVIES WTC QUALTPy m^CT^^ A 20000112 078 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reDOrtino burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, a^^r^6<^mim\ngxh^a^BäJ, and completing and reviewing the collection of information Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any^othe aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Inforrnatior.Ope.rations and Reporte, 1215 Jefferson Davfei wShwa? Suit? 1:204 Arlington: VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Pro]ect (0704-01881, Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 3Jan.OO MAJOR REPORT 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE IMPOSITION OF MARTIAL LAW IN UNITED STATES 6. AUTHOR(S) MAJ DAVIES KIRK L 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER JA GENERAL SCHOOL ARMY 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY REPORT NUMBER THE DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AFIT/CIA, BLDG 125 FY99-603 2950 P STREET WPAFB OH 45433 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE Unlimited distribution In Accordance With AFI 35-205/AFIT Sup 1 13. ABSTRACT tMaximum 200 words) DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES 61 16. -

World War I Posters and the Female Form

WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER Bachelor of Arts in English John Carroll University January, 2003 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTERS OF ARTS IN HISTORY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2008 This thesis has been approved for the Department of ART HISTORY and the College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Samantha Baskind _________________________ Department & Date ____________________________________________ Dr. Marian Bleeke ________________________ Department & Date _____________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Lehfeldt ___________________________ Department & Date WORLD WAR I POSTERS AND THE FEMALE FORM: ASSERTING OWNERSHIP OF THE AMERICAN WOMAN LAURA M. ROTHER ABSTRACT Like Britain and continental Europe, the United States would utilize the poster to garner both funding and public support during World War I. While war has historically been considered a masculine endeavor, a relatively large number of these posters depict the female form. Although the use of women in American World War I visual propaganda may not initially seem problematic, upon further inspection it becomes clear that her presence often served to promote racial and national pretentiousness. Based on the works of popular pre-war illustrators like Howard Chandler Christy and Charles Dana Gibson, the American woman was the most attractive woman in the in the world. Her outstanding wit, beauty and intelligence made her the only suitable mate for the supposed racially superior American man. With the onset of war, however, the once entertaining romantic scenarios in popular monthlies and weeklies now represented what America stood to lose, and the “American Girl” would make the transition from magazine illustrations to war poster with minimal alterations.