DIAPH3)/ Diaphanous Causes Hearing Defects in Humans with Auditory Neuropathy and in Drosophila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exceptional Conservation of Horse–Human Gene Order on X Chromosome Revealed by High-Resolution Radiation Hybrid Mapping

Exceptional conservation of horse–human gene order on X chromosome revealed by high-resolution radiation hybrid mapping Terje Raudsepp*†, Eun-Joon Lee*†, Srinivas R. Kata‡, Candice Brinkmeyer*, James R. Mickelson§, Loren C. Skow*, James E. Womack‡, and Bhanu P. Chowdhary*¶ʈ *Department of Veterinary Anatomy and Public Health, ‡Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, and ¶Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Life Science, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; and §Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Minnesota, 295f AS͞VM, St. Paul, MN 55108 Contributed by James E. Womack, December 30, 2003 Development of a dense map of the horse genome is key to efforts ciated with the traits, once they are mapped by genetic linkage aimed at identifying genes controlling health, reproduction, and analyses with highly polymorphic markers. performance. We herein report a high-resolution gene map of the The X chromosome is the most conserved mammalian chro- horse (Equus caballus) X chromosome (ECAX) generated by devel- mosome (18, 19). Extensive comparisons of structure, organi- oping and typing 116 gene-specific and 12 short tandem repeat zation, and gene content of this chromosome in evolutionarily -markers on the 5,000-rad horse ؋ hamster whole-genome radia- diverse mammals have revealed a remarkable degree of conser tion hybrid panel and mapping 29 gene loci by fluorescence in situ vation (20–22). Until now, the chromosome has been best hybridization. The human X chromosome sequence was used as a studied in humans and mice, where the focus of research has template to select genes at 1-Mb intervals to develop equine been the intriguing patterns of X inactivation and the involve- orthologs. -

Snapshot: Formins Christian Baarlink, Dominique Brandt, and Robert Grosse University of Marburg, Marburg 35032, Germany

SnapShot: Formins Christian Baarlink, Dominique Brandt, and Robert Grosse University of Marburg, Marburg 35032, Germany Formin Regulators Localization Cellular Function Disease Association DIAPH1/DIA1 RhoA, RhoC Cell cortex, Polarized cell migration, microtubule stabilization, Autosomal-dominant nonsyndromic deafness (DFNA1), myeloproliferative (mDia1) phagocytic cup, phagocytosis, axon elongation defects, defects in T lymphocyte traffi cking and proliferation, tumor cell mitotic spindle invasion, defects in natural killer lymphocyte function DIAPH2 Cdc42 Kinetochore Stable microtubule attachment to kinetochore for Premature ovarian failure (mDia3) chromosome alignment DIAPH3 Rif, Cdc42, Filopodia, Filopodia formation, removing the nucleus from Increased chromosomal deletion of gene locus in metastatic tumors (mDia2) Rac, RhoB, endosomes erythroblast, endosome motility, microtubule DIP* stabilization FMNL1 (FRLα) Cdc42 Cell cortex, Phagocytosis, T cell polarity Overexpression is linked to leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma microtubule- organizing center FMNL2/FRL3/ RhoC ND Cell motility Upregulated in metastatic colorectal cancer, chromosomal deletion is FHOD2 associated with mental retardation FMNL3/FRL2 Constituently Stress fi bers ND ND active DAAM1 Dishevelled Cell cortex Planar cell polarity ND DAAM2 ND ND ND Overexpressed in schizophrenia patients Human (Mouse) FHOD1 ROCK Stress fi bers Cell motility FHOD3 ND Nestin, sarcomere Organizing sarcomeres in striated muscle cells Single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with type 1 diabetes -

Defining Functional Interactions During Biogenesis of Epithelial Junctions

ARTICLE Received 11 Dec 2015 | Accepted 13 Oct 2016 | Published 6 Dec 2016 | Updated 5 Jan 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13542 OPEN Defining functional interactions during biogenesis of epithelial junctions J.C. Erasmus1,*, S. Bruche1,*,w, L. Pizarro1,2,*, N. Maimari1,3,*, T. Poggioli1,w, C. Tomlinson4,J.Lees5, I. Zalivina1,w, A. Wheeler1,w, A. Alberts6, A. Russo2 & V.M.M. Braga1 In spite of extensive recent progress, a comprehensive understanding of how actin cytoskeleton remodelling supports stable junctions remains to be established. Here we design a platform that integrates actin functions with optimized phenotypic clustering and identify new cytoskeletal proteins, their functional hierarchy and pathways that modulate E-cadherin adhesion. Depletion of EEF1A, an actin bundling protein, increases E-cadherin levels at junctions without a corresponding reinforcement of cell–cell contacts. This unexpected result reflects a more dynamic and mobile junctional actin in EEF1A-depleted cells. A partner for EEF1A in cadherin contact maintenance is the formin DIAPH2, which interacts with EEF1A. In contrast, depletion of either the endocytic regulator TRIP10 or the Rho GTPase activator VAV2 reduces E-cadherin levels at junctions. TRIP10 binds to and requires VAV2 function for its junctional localization. Overall, we present new conceptual insights on junction stabilization, which integrate known and novel pathways with impact for epithelial morphogenesis, homeostasis and diseases. 1 National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 2 Computing Department, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 3 Bioengineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 4 Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. -

Identification of Common Gene Networks Responsive To

Cancer Gene Therapy (2014) 21, 542–548 © 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0929-1903/14 www.nature.com/cgt ORIGINAL ARTICLE Identification of common gene networks responsive to radiotherapy in human cancer cells D-L Hou1, L Chen2, B Liu1, L-N Song1 and T Fang1 Identification of the genes that are differentially expressed between radiosensitive and radioresistant cancers by global gene analysis may help to elucidate the mechanisms underlying tumor radioresistance and improve the efficacy of radiotherapy. An integrated analysis was conducted using publicly available GEO datasets to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between cancer cells exhibiting radioresistance and cancer cells exhibiting radiosensitivity. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis and protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks analysis were also performed. Five GEO datasets including 16 samples of radiosensitive cancers and radioresistant cancers were obtained. A total of 688 DEGs across these studies were identified, of which 374 were upregulated and 314 were downregulated in radioresistant cancer cell. The most significantly enriched GO terms were regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent (GO: 0006355, P = 7.00E-09) for biological processes, while those for molecular functions was protein binding (GO: 0005515, P = 1.01E-28), and those for cellular component was cytoplasm (GO: 0005737, P = 2.81E-26). The most significantly enriched pathway in our KEGG analysis was Pathways in cancer (P = 4.20E-07). PPI network analysis showed that IFIH1 (Degree = 33) was selected as the most significant hub protein. This integrated analysis may help to predict responses to radiotherapy and may also provide insights into the development of individualized therapies and novel therapeutic targets. -

Prediction of Human Disease Genes by Human-Mouse Conserved Coexpression Analysis

Prediction of Human Disease Genes by Human-Mouse Conserved Coexpression Analysis Ugo Ala1., Rosario Michael Piro1., Elena Grassi1, Christian Damasco1, Lorenzo Silengo1, Martin Oti2, Paolo Provero1*, Ferdinando Di Cunto1* 1 Molecular Biotechnology Center, Department of Genetics, Biology and Biochemistry, University of Turin, Turin, Italy, 2 Department of Human Genetics and Centre for Molecular and Biomolecular Informatics, University Medical Centre Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract Background: Even in the post-genomic era, the identification of candidate genes within loci associated with human genetic diseases is a very demanding task, because the critical region may typically contain hundreds of positional candidates. Since genes implicated in similar phenotypes tend to share very similar expression profiles, high throughput gene expression data may represent a very important resource to identify the best candidates for sequencing. However, so far, gene coexpression has not been used very successfully to prioritize positional candidates. Methodology/Principal Findings: We show that it is possible to reliably identify disease-relevant relationships among genes from massive microarray datasets by concentrating only on genes sharing similar expression profiles in both human and mouse. Moreover, we show systematically that the integration of human-mouse conserved coexpression with a phenotype similarity map allows the efficient identification of disease genes in large genomic regions. Finally, using this approach on 850 OMIM loci characterized by an unknown molecular basis, we propose high-probability candidates for 81 genetic diseases. Conclusion: Our results demonstrate that conserved coexpression, even at the human-mouse phylogenetic distance, represents a very strong criterion to predict disease-relevant relationships among human genes. Citation: Ala U, Piro RM, Grassi E, Damasco C, Silengo L, et al. -

Genetic Determinants of Ovarian Reserve

Genetic determinants of ovarian reserve Daniela Toniolo Daniela Toniolo DIBIT- San Raffaele Scientific Foundation Milano, Italy Women fertility starts to decrease around 30 years 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 Relative fertility Relative 0 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 Age (years) Woman ageetà (years) From Noord -Zaadstra et al. 2001 1 Premature Ovarian Failure Disorder of ovulation characterized by: Elevated levels of gonadotropins before the age of 40 Primary or secondary amernorrhea or early menopause Ovaries reduced or absent Ovarian follicles reduced or absent Corresponds to about 10% of female sterility Its relevance is increasing with the increase in the age of first child bearing Premature Ovarian Failure has a genetic basis 30-40% are familial cases Mutations in genes responsible for rare genetic forms inherited as autosomal recessive (FSHR), X-linked dominant (BMP15, NOBOX) and syndromic forms (FOXL2, E1F2b) very low epidemiologic relevance FRAXA premutation is a common risk-factor 20-30% of women with premutation have POF (OR=21; 95%CI:15-27) 3-5% of POF affected women carry a FRAXA premutated allele (about 13% of familial cases-about 2% of sporadic cases) POF seems to behave also as a complex disorder caused by several risk genetic factors 2 Large deletions of the X chromosome are associated with POF 6570 75 80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140 145 150 q11 q12 q13 q21 q22 q23 q24 q25 q26 q27 q28 Deletions no POF POF the rarity of small monosomies is in favor of a cumulative effect of the large deletions on several genes of the X chromosome long arm and of POF as a complex disorder 1. -

Transdifferentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Transdifferentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Tatjana Schilling aus San Miguel de Tucuman, Argentinien Würzburg, 2007 Eingereicht am: Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Martin J. Müller Gutachter: PD Dr. Norbert Schütze Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Georg Krohne Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am: Hiermit erkläre ich ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation selbstständig angefertigt und keine anderen als die von mir angegebenen Hilfsmittel und Quellen verwendet habe. Des Weiteren erkläre ich, dass diese Arbeit weder in gleicher noch in ähnlicher Form in einem Prüfungsverfahren vorgelegen hat und ich noch keinen Promotionsversuch unternommen habe. Gerbrunn, 4. Mai 2007 Tatjana Schilling Table of contents i Table of contents 1 Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Summary.................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Zusammenfassung..................................................................................................... 2 2 Introduction.................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Osteoporosis and the fatty degeneration of the bone marrow..................................... 4 2.2 Adipose and bone -

Patterns of Molecular Evolution of an Avian Neo-Sex Chromosome

Patterns of Molecular Evolution of an Avian Neo-sex Chromosome Irene Pala,*,1 Dennis Hasselquist,1 Staffan Bensch,1 and Bengt Hansson*,1 1Molecular Ecology and Evolution Lab, Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Associate editor: Yoko Satta Abstract Newer parts of sex chromosomes, neo-sex chromosomes, offer unique possibilities for studying gene degeneration and sequence evolution in response to loss of recombination and population size decrease. We have recently described a neo-sex chromosome Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/29/12/3741/1005710 by guest on 28 September 2021 system in Sylvioidea passerines that has resulted from a fusion between the first half (10 Mb) of chromosome 4a and the ancestral Research article sex chromosomes. In this study, we report the results of molecular analyses of neo-Z and neo-W gametologs and intronic parts of neo-Z and autosomal genes on the second half of chromosome 4a in three species within different Sylvioidea lineages (Acrocephalidea, Timaliidae, and Alaudidae). In line with hypotheses of neo-sex chromosome evolution, we observe 1) lower genetic diversity of neo-Z genes compared with autosomal genes, 2) moderate synonymous and weak nonsynonymous sequence divergence between neo-Z and neo-W gametologs, and 3) lower GC content on neo-W than neo-Z gametologs. Phylogenetic reconstruction of eight neo-Z and neo-W gametologs suggests that recombination continued after the split of Alaudidae from the rest of the Sylvioidea lineages (i.e., after 42.2 Ma) and with some exceptions also after the split of Acrocephalidea and Timaliidae (i.e., after 39.4 Ma). -

Downloaded from Bioscientifica.Com at 09/28/2021 09:08:00AM Via Free Access

245 E L Woodward et al. Genetic changes in anaplastic 24:5 209–220 Research thyroid cancer Genomic complexity and targeted genes in anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines Eleanor L Woodward1, Andrea Biloglav1, Naveen Ravi1, Minjun Yang1, Lars Ekblad2, Johan Wennerberg3 and Kajsa Paulsson1 1Division of Clinical Genetics, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden Correspondence 2Division of Oncology and Pathology, Clinical Sciences, Lund University and Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden should be addressed 3Division of Otorhinolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery, Clinical Sciences, Lund University and Skåne to K Paulsson University Hospital, Lund, Sweden Email [email protected] Abstract Anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) is a highly malignant disease with a very short median Key Words survival time. Few studies have addressed the underlying somatic mutations, and the f thyroid genomic landscape of ATC thus remains largely unknown. In the present study, we f molecular genetics have ascertained copy number aberrations, gene fusions, gene expression patterns, f gene expression and mutations in early-passage cells from ten newly established ATC cell lines using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array analysis, RNA sequencing and whole exome sequencing. The ATC cell line genomes were highly complex and displayed signs of replicative stress and genomic instability, including massive aneuploidy and frequent Endocrine-Related Cancer Endocrine-Related breakpoints in the centromeric regions and in fragile sites. Loss of heterozygosity involving whole chromosomes was common, but there were no signs of previous near- haploidisation events or chromothripsis. A total of 21 fusion genes were detected, including six predicted in-frame fusions; none were recurrent. -

Rhod Participates in the Regulation of Cell-Cycle Progression and Centrosome Duplication

Oncogene (2013) 32, 1831–1842 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/13 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE RhoD participates in the regulation of cell-cycle progression and centrosome duplication A Kyrkou1,2, M Soufi1, R Bahtz3, C Ferguson4, M Bai5, RG Parton4, I Hoffmann3, M Zerial6, T Fotsis1,2 and C Murphy2 We have previously identified a Rho protein, RhoD, which localizes to the plasma membrane and the early endocytic compartment. Here, we show that a GTPase-deficient mutant of RhoD, RhoDG26V, causes hyperplasia and perturbed differentiation of the epidermis, when targeted to the skin of transgenic mice. In vitro, gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches revealed that RhoD is involved in the regulation of G1/S-phase progression and causes overduplication of centrosomes. Centriole overduplication assays in aphidicolin-arrested p53-deficient U2OS cells, in which the cell and the centrosome cycles are uncoupled, revealed that the effects of RhoD and its mutants on centrosome duplication and cell cycle are independent. Enhancement of G1/S-phase progression was mediated via Diaph1, a novel effector of RhoD, which we have identified using a two-hybrid screen. These results indicate that RhoD participates in the regulation of cell-cycle progression and centrosome duplication. Oncogene (2013) 32, 1831–1842; doi:10.1038/onc.2012.195; published online 4 June 2012 Keywords: RhoD; proliferation; centrosome cycle INTRODUCTION We have previously identified a Rho GTPase, RhoD and shown The human Rho family of small GTPases represents a major branch that it is localized on early endosomes, through which it alters 14 of the Ras superfamily, which participates in the regulation of membrane dynamics in the endocytic pathway and inhibits the 15 16 various processes such as the formation of cellular protrusions, motility of endothelial and 10T1/2 cells. -

Anti-DIAPH2 Antibody (ARG58499)

Product datasheet [email protected] ARG58499 Package: 100 μl anti-DIAPH2 antibody Store at: -20°C Summary Product Description Rabbit Polyclonal antibody recognizes DIAPH2 Tested Reactivity Hu, Ms, Rat Tested Application WB Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Target Name DIAPH2 Antigen Species Human Immunogen Recombinant fusion protein corresponding to aa. 1-120 of Human DIAPH2 (NP_009293.1). Conjugation Un-conjugated Alternate Names Diaphanous-related formin-2; DRF2; Protein diaphanous homolog 2; POF2; DIA; POF; DIA2 Application Instructions Application table Application Dilution WB 1:1000 - 1:2000 Application Note * The dilutions indicate recommended starting dilutions and the optimal dilutions or concentrations should be determined by the scientist. Positive Control H460 Calculated Mw 126 kDa Observed Size 135 kDa Properties Form Liquid Purification Affinity purified. Buffer PBS (pH 7.3), 0.02% Sodium azide and 50% Glycerol. Preservative 0.02% Sodium azide Stabilizer 50% Glycerol Storage instruction For continuous use, store undiluted antibody at 2-8°C for up to a week. For long-term storage, aliquot and store at -20°C. Storage in frost free freezers is not recommended. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Suggest spin the vial prior to opening. The antibody solution should be gently mixed before use. Note For laboratory research only, not for drug, diagnostic or other use. www.arigobio.com 1/2 Bioinformation Gene Symbol DIAPH2 Gene Full Name diaphanous-related formin 2 Background The product of this gene belongs to the diaphanous subfamily of the formin homology family of proteins. This gene may play a role in the development and normal function of the ovaries. -

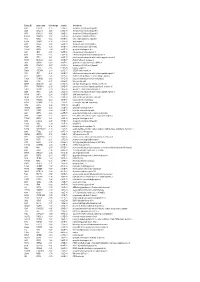

Entrez ID Gene Name Fold Change Q-Value Description

Entrez ID gene name fold change q-value description 4283 CXCL9 -7.25 5.28E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 3627 CXCL10 -6.88 6.58E-05 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 6373 CXCL11 -5.65 3.69E-04 chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 405753 DUOXA2 -3.97 3.05E-06 dual oxidase maturation factor 2 4843 NOS2 -3.62 5.43E-03 nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible 50506 DUOX2 -3.24 5.01E-06 dual oxidase 2 6355 CCL8 -3.07 3.67E-03 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 10964 IFI44L -3.06 4.43E-04 interferon-induced protein 44-like 115362 GBP5 -2.94 6.83E-04 guanylate binding protein 5 3620 IDO1 -2.91 5.65E-06 indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 8519 IFITM1 -2.67 5.65E-06 interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 3433 IFIT2 -2.61 2.28E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 54898 ELOVL2 -2.61 4.38E-07 ELOVL fatty acid elongase 2 2892 GRIA3 -2.60 3.06E-05 glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 3 6376 CX3CL1 -2.57 4.43E-04 chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 7098 TLR3 -2.55 5.76E-06 toll-like receptor 3 79689 STEAP4 -2.50 8.35E-05 STEAP family member 4 3434 IFIT1 -2.48 2.64E-03 interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 4321 MMP12 -2.45 2.30E-04 matrix metallopeptidase 12 (macrophage elastase) 10826 FAXDC2 -2.42 5.01E-06 fatty acid hydroxylase domain containing 2 8626 TP63 -2.41 2.02E-05 tumor protein p63 64577 ALDH8A1 -2.41 6.05E-06 aldehyde dehydrogenase 8 family, member A1 8740 TNFSF14 -2.40 6.35E-05 tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 14 10417 SPON2 -2.39 2.46E-06 spondin 2, extracellular matrix protein 3437