Vivaldi's Bohemian Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

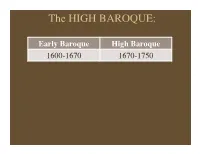

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, Concert Partner

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, concert partner The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Student Concerts are generously supported by Mrs. Gert Wharton and an anonymous donor. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges Sarah Greenfield for preparing the lesson plans for the Junior/Intermediate Student Concert Study Guide. Junior/Intermediate Level Student Concert Study Guide Study Concert Student Level Junior/Intermediate Table of Contents Table of Contents 1) Concert Overview & Repertoire Page 3 2) Composer Biographies and Programme Notes Page 4 - 11 3) Unit Overview & Lesson Plans Page 12 - 23 4) Lesson Plan Answer Key Page 24 - 30 5) Artist Biographies Page 32 - 34 6) Musical Terms Glossary Page 35 - 36 7) Instruments in the Orchestra Page 37 - 45 8) Orchestra Seating Chart Page 46 9) Musicians of the TSO Page 47 10) Concert Preparation Page 48 11) Evaluation Forms (teacher and student) Page 49 - 50 The TSO has created a free podcast to help you prepare your students for the Science @ the Symphony Student Concerts. This podcast includes excerpts from pieces featured on the programme, as well as information about the instruments featured in each selection. It is intended for use either in the classroom, or to be assigned as homework. To download the TSO Junior/Intermediate Student Concert podcast please visit www.tso.ca/studentconcerts, and follow the links on the top bar to Junior/Intermediate. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra wishes to thank its generous sponsors: SEASON PRESENTING SPONSOR OFFICIAL AIRLINE SEASON -

Two Operatic Seasons of Brothers Mingotti in Ljubljana

Prejeto / received: 30. 11. 2012. Odobreno / accepted: 19. 12. 2012. tWo OPERATIC SEASONS oF BROTHERS MINGOTTI IN LJUBLJANA METODA KOKOLE Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Ljubljana Izvleček: Brata Angelo in Pietro Mingotti, ki sta Abstract: The brothers Angelo and Pietro med 1736 in 1746 imela stalno gledališko posto- Mingotti between 1736 and 1746 based in Graz janko v Gradcu, sta v tem času priredila tudi dve organised during this period also two operatic operni sezoni v Ljubljani, in sicer v letih 1740 seasons in Ljubljana, one in 1740 and the other in 1742. Dve resni operi (Artaserse in Rosmira) in 1742. Two serious operas (Artaserse and s komičnimi intermezzi (Pimpinone e Vespetta) Rosmira) with comic intermezzi (Pimpinone e je leta 1740 pripravil Angelo Mingotti, dve leti Vespetta) were produced in 1740 by Angelo Min- zatem, tik pred svojim odhodom iz Gradca na gotti. Two years later, just before leaving Graz sever, pa je Pietro Mingotti priredil nadaljnji for the engagements in the North, Pietro Mingotti dve resni operi, in sicer Didone abbandonata in brought another two operas to Ljubljana, Didone Il Demetrio. Prvo je nato leta 1744 priredil tudi v abbandonata and Il Demetrio. The former was Hamburgu, kjer je pelo nekaj že znanih pevcev, ki performed also in 1744 in Hamburg with some so izvajali iz starejše partiture, morda tiste, ki jo of the same singers who apparently used mostly je impresarij preizkusil že v Gradcu in Ljubljani. an earlier score, possibly first checked out in Primerjalna analiza ljubljanskih predstav vseka- Graz and Ljubljana. The comparative analysis kor potrjuje dejstvo, da so bile te opera pretežno of productions in Ljubljana confirms that these lepljenke, čeprav Pietrova Didone abbandonata operas were mostly pasticcios. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

TCB Groove Program

www.piccolotheatre.com 224-420-2223 T-F 10A-5P 37 PLAYS IN 80-90 MINUTES! APRIL 7- MAY 14! SAVE THE DATE! NOVEMBER 10, 11, & 12 APRIL 21 7:30P APRIL 22 5:00P APRIL 23 2:00P NICHOLS CONCERT HALL BENITO JUAREZ ST. CHRYSOSTOM’S Join us for the powerful polyphony of MUSIC INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO COMMUNITY ACADEMY EPISCOPAL CHURCH G.F. Handel's As pants the hart, 1490 CHICAGO AVE PERFORMING ARTS CENTER 1424 N DEARBORN ST. EVANSTON, IL 60201 1450 W CERMAK RD CHICAGO, IL 60610 Domenico Scarlatti's Stabat mater, TICKETS $10-$40 CHICAGO, IL 60608 TICKETS $10-$40 and J.S. Bach's Singet dem Herrn. FREE ADMISSION Dear friends, Last fall, Third Coast Baroque’s debut series ¡Sarabanda! focused on examining the African and Latin American folk music roots of the sarabande. Today, we will be following the paths of the chaconne, passacaglia and other ostinato rhythms – with origins similar to the sarabande – as they spread across Europe during the 17th century. With this program that we are calling Groove!, we present those intoxicating rhythms in the fashion and flavor of the different countries where they gained popularity. The great European composers wrote masterpieces using the rhythms of these ancient dances to create immortal pieces of art, but their weight and significance is such that we tend to forget where their origins lie. Bach, Couperin, and Purcell – to name only a few – wrote music for highly sophisticated institutions. Still, through these dance rhythms, they were searching for something similar to what the more ancient civilizations had been striving to attain: a connection to the spiritual world. -

III CHAPTER III the BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – Flamboyant, Elaborately Ornamented A. Characteristic

III CHAPTER III THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1. Baroque Music (1600-1750) Baroque – flamboyant, elaborately ornamented a. Characteristics of Baroque Music 1. Unity of Mood – a piece expressed basically one basic mood e.g. rhythmic patterns, melodic patterns 2. Rhythm – rhythmic continuity provides a compelling drive, the beat is more emphasized than before. 3. Dynamics – volume tends to remain constant for a stretch of time. Terraced dynamics – a sudden shift of the dynamics level. (keyboard instruments not capable of cresc/decresc.) 4. Texture – predominantly polyphonic and less frequently homophonic. 5. Chords and the Basso Continuo (Figured Bass) – the progression of chords becomes prominent. Bass Continuo - the standard accompaniment consisting of a keyboard instrument (harpsichord, organ) and a low melodic instrument (violoncello, bassoon). 6. Words and Music – Word-Painting - the musical representation of specific poetic images; E.g. ascending notes for the word heaven. b. The Baroque Orchestra – Composed of chiefly the string section with various other instruments used as needed. Size of approximately 10 – 40 players. c. Baroque Forms – movement – a piece that sounds fairly complete and independent but is part of a larger work. -Binary and Ternary are both dominant. 2. The Concerto Grosso and the Ritornello Form - concerto grosso – a small group of soloists pitted against a larger ensemble (tutti), usually consists of 3 movements: (1) fast, (2) slow, (3) fast. - ritornello form - e.g. tutti, solo, tutti, solo, tutti solo, tutti etc. Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Title on autograph score: Concerto 2do à 1 Tromba, 1 Flauto, 1 Hautbois, 1 Violino concertati, è 2 Violini, 1 Viola è Violone in Ripieno col Violoncello è Basso per il Cembalo. -

Antonio Vivaldi Born: March 4, 1678 Died: July 28, 1741

“Spring” from The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi Born: March 4, 1678 Died: July 28, 1741 Antonio Vivaldi was born in institution became famous, Venice, Italy, which is where and people came from miles he spent most of his life. around the hear Vivaldi’s His father, a professional talented students perform the musician at St. Mark’s beautiful music he had written Church, taught him to play for them. the violin, and the two often performed together. Vivaldi was one of the best composers of his time. Although Vivaldi was He wrote operas, sonatas ordained a priest in the and choral works, but is Catholic Church (he was particularly known for his called the “Red Priest” concertos (he composed over because of his flaming 500, although many have red hair), health problems been lost). One of the most prevented him from famous sets is The Four celebrating the Mass and Seasons. After his death, he was not associated with Vivaldi’s music was virtually any one particular church. forgotten for many years. He continued to study However, in the early 1900’s, and practice the violin many of his original scores and became a teacher at were rediscovered and his a Venetian orphanage for popularity and reputation have young girls, a position continued to grow since that he held for the rest of his time. life. The orchestra of this Antonio Vivaldi Spring Spring has come, and joyfully 1. This concerto has a feeling of: the birds welcome it with cheerful song, and the streams, a. constant motion and change caressed by the breath of zephyrs, b. -

Unwrap the Music Concerts with Commentary

UNWRAP THE MUSIC CONCERTS WITH COMMENTARY UNWRAP VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS – SUMMER AND WINTER Eugenie Middleton and Peter Thomas UNWRAP THE MUSIC VIVALDI’S FOUR SEASONS SUMMER AND WINTER INTRODUCTION & INDEX This unit aims to provide teachers with an easily usable interactive resource which supports the APO Film “Unwrap the Music: Vivaldi’s Four Seasons – Summer and Winter”. There are a range of activities which will see students gain understanding of the music of Vivaldi, orchestral music and how music is composed. It provides activities suitable for primary, intermediate and secondary school-aged students. BACKGROUND INFORMATION CREATIVE TASKS 2. Vivaldi – The Composer 40. Art Tasks 3. The Baroque Era 45. Creating Music and Movement Inspired by the Sonnets 5. Sonnets – Music Inspired by Words 47. 'Cuckoo' from Summer Xylophone Arrangement 48. 'Largo' from Winter Xylophone Arrangement ACTIVITIES 10. Vivaldi Listening Guide ASSESSMENTS 21. Transcript of Film 50. Level One Musical Knowledge Recall Assessment 25. Baroque Concerto 57. Level Two Musical Knowledge Motif Task 28. Programme Music 59. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task 31. Basso Continuo 64. Level Three Musical Knowledge Class Research Task – 32. Improvisation Examples of Student Answers 33. Contrasts 69. Level Three Musical Knowledge Analysis Task 34. Circle of Fifths 71. Level Three Context Questions 35. Ritornello Form 36. Relationship of Rhythm 37. Wordfind 38. Terminology Task 1 ANTONIO VIVALDI The Composer Antonio Vivaldi was born and lived in Italy a musical education and the most talented stayed from 1678 – 1741. and became members of the institution’s renowned He was a Baroque composer and violinist. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

Teuzzone Vivaldi

TEUZZONE VIVALDI Fitxa / Ficha Vivaldi se’n va a la Xina / 11 41 Vivaldi se va a China Xavier Cester Repartiment / Reparto 12 Teuzzone o les meravelles 57 d’Antonio Vivaldi / Teuzzone o las maravillas Amb el teló abaixat / de Antonio Vivaldi 15 A telón bajado Manuel Forcano 21 Argument / Argumento 68 Cronologia / Cronología 33 English Synopsis 84 Biografies / Biografías x x Temporada 2016/17 Amb el suport del Departament de Cultura de la Generalitat de Catalunyai la Diputació de Barcelona TEUZZONE Òpera en tres actes. Llibret d’Apostolo Zeno. Música d’Antonio Vivaldi Ópera en tres actos. Libreto de Apostolo Zeno. Música de Antonio Vivaldi Estrenes / Estrenos Carnestoltes 1719: Estrena absoluta al Teatro Arciducale de Màntua / Estreno absoluto en el Teatro Arciducale de Mantua Estrena a Espanya / Estreno en España Febrer / Febrero 2017 Torn / Turno Tarifa 24 20.00 h G 8 25 18.00 h F 8 Durada total aproximada 3h 15m Uneix-te a la conversa / Únete a la conversación liceubarcelona.cat #TeuzzoneLiceu facebook.com/liceu @liceu_cat @liceu_opera_barcelona 12 pag. Repartiment / Reparto 13 Teuzzone, fill de l’emperador de Xina Paolo Lopez Teuzzone, hijo del emperador de China Zidiana, jove vídua de Troncone Marta Fumagalli Zidiana, joven viuda de Troncone Zelinda, princesa tàrtara Sonia Prina Zelinda, princesa tártara Sivenio, general del regne Furio Zanasi Sivenio, general del reino Cino, primer ministre Roberta Mameli Cino, primer ministro Egaro, capità de la guàrdia Aurelio Schiavoni Egaro, capitán de la guardia Troncone / Argonte, emperador Carlo Allemano de Xina / príncep tàrtar Troncone / Argonte, emperador de China / príncipe tártaro Direcció musical Jordi Savall Dirección musical Le Concert des Nations Concertino Manfredo Kraemer Sobretítols / Sobretítulos Glòria Nogué, Anabel Alenda 14 pag. -

Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra to Perform June 1

Skip to Content Cal Poly News Search Cal Poly News Go California Polytechnic State University May 15, 2002 Contact: Jo Ann Lloyd (805) 756-1511 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra To Perform June 1 The Cal Poly Chamber Orchestra and some of the university's leading musicians and singers will perform music by Béla Bartók, Antonio Vivaldi, Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Franz Schubert in its Spring Concert at 8 p.m. June 1 in the Theatre on campus. Founder and Music Professor Clifton Swanson will conduct the orchestra. Mi Young Shin, a 2000 graduate of the Cal Poly music program and assistant conductor of the orchestra, will lead the ensemble in a performance of Bartók's "Rumanian Dances," which include seven folk dances: the stick dance and sash dance, "in one spot," the horn dance, a Rumanian polka, and two fast dances. The orchestra will also perform with winners of the Music Department's solo competition, which was held in March. Recent Music Department graduate Jessica Getman, oboist, will perform the Allegro non molto from Vivaldi's Concerto in A minor for oboe and strings. In addition, three sopranos will perform. Business administration major Veronica Cull will sing "Stizzoso, mio stizzoso, voi fatte il borioso" from Pergolesi's "La Serva Padrona." Music major Valerie Laxson will perform Mozart's "Vedrai, carino, se sei buonino" from the opera "Don Giovanni." Music major Jennifer Cecil will sing the well-known "Alleluia" from Mozart's motet "Exsultate, jubilate," with Shin conducting. The concert will conclude with Schubert's Symphony No. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Matthias Bernhard Braun auf seinem Weg nach Böhmen“ Verfasserin Anneliese Schallmeiner angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 315 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao Prof. Dr. Walter Krause Inhalt Seite I. Einleitung 4 II. Biographischer Abriss und Forschungslage 8 1. Biographischer Abriss zu Matthias Bernhard Braun 8 2. Forschungslage 13 III. Matthias Bernhard Braun auf seinem Weg nach Böhmen 22 1. Stilanalytische Überlegungen 22 2. Von Stams nach Plass/Plasy – Die Bedeutung des Zisterzienserordens – 27 Eine Hypothese 2.1. Brauns Arbeiten für das Zisterzienserkloster in Plass/Plasy 32 2.1.1. Die Kalvarienberggruppe 33 2.1.2. Die Verkündigungsgruppe 36 2.1.3. Der Bozzetto zur Statuengruppe der hl. Luitgard auf der Karlsbrücke 39 3. Die Statuengruppen auf der Karlsbrücke in Prag 41 3.1. Die Statuengruppe der hl. Luitgard 47 3.1.1. Kompositionelle und ikonographische Vorbilder 50 3.1.2. Visionäre und mysthische Vorbilder 52 3.2. Die Statuengruppe des hl. Ivo 54 3.2.1. Kompositionelle Vorbilder 54 3.2.2. Die Statue des hl. Franz Borgia von Ferdinand Maximilian Brokoff als 55 mögliches Vorbild für die Statue des hl. Ivo 4. Die Statue des hl. Judas Thaddäus 57 5. Brauns Beitrag zur Ausstattung der St. Klemenskirche in Prag 59 5.1. Evangelisten und Kirchenväter 60 5.2. Die Beichtstuhlaufsatzfiguren 63 6. Die Bedeutung des Grafen Franz Anton von Sporck für den Weg von 68 Matthias Bernhard Braun nach Böhmen 6.1.