The International Congresses of Mathematicians - Politics and Mathematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E

BOOK REVIEW Einstein’s Italian Mathematicians: Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the Birth of General Relativity Reviewed by David E. Rowe Einstein’s Italian modern Italy. Nor does the author shy away from topics Mathematicians: like how Ricci developed his absolute differential calculus Ricci, Levi-Civita, and the as a generalization of E. B. Christoffel’s (1829–1900) work Birth of General Relativity on quadratic differential forms or why it served as a key By Judith R. Goodstein tool for Einstein in his efforts to generalize the special theory of relativity in order to incorporate gravitation. In This delightful little book re- like manner, she describes how Levi-Civita was able to sulted from the author’s long- give a clear geometric interpretation of curvature effects standing enchantment with Tul- in Einstein’s theory by appealing to his concept of parallel lio Levi-Civita (1873–1941), his displacement of vectors (see below). For these and other mentor Gregorio Ricci Curbastro topics, Goodstein draws on and cites a great deal of the (1853–1925), and the special AMS, 2018, 211 pp. 211 AMS, 2018, vast secondary literature produced in recent decades by the world that these and other Ital- “Einstein industry,” in particular the ongoing project that ian mathematicians occupied and helped to shape. The has produced the first 15 volumes of The Collected Papers importance of their work for Einstein’s general theory of of Albert Einstein [CPAE 1–15, 1987–2018]. relativity is one of the more celebrated topics in the history Her account proceeds in three parts spread out over of modern mathematical physics; this is told, for example, twelve chapters, the first seven of which cover episodes in [Pais 1982], the standard biography of Einstein. -

European Mathematical Society

CONTENTS EDITORIAL TEAM EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARTIN RAUSSEN Department of Mathematical Sciences, Aalborg University Fredrik Bajers Vej 7G DK-9220 Aalborg, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS VASILE BERINDE Department of Mathematics, University of Baia Mare, Romania NEWSLETTER No. 52 e-mail: [email protected] KRZYSZTOF CIESIELSKI Mathematics Institute June 2004 Jagiellonian University Reymonta 4, 30-059 Kraków, Poland EMS Agenda ........................................................................................................... 2 e-mail: [email protected] STEEN MARKVORSEN Editorial by Ari Laptev ........................................................................................... 3 Department of Mathematics, Technical University of Denmark, Building 303 EMS Summer Schools.............................................................................................. 6 DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark EC Meeting in Helsinki ........................................................................................... 6 e-mail: [email protected] ROBIN WILSON On powers of 2 by Pawel Strzelecki ........................................................................ 7 Department of Pure Mathematics The Open University A forgotten mathematician by Robert Fokkink ..................................................... 9 Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK e-mail: [email protected] Quantum Cryptography by Nuno Crato ............................................................ 15 COPY EDITOR: KELLY -

Lecture Notes for Felix Klein Lectures

Preprint typeset in JHEP style - HYPER VERSION Lecture Notes for Felix Klein Lectures Gregory W. Moore Abstract: These are lecture notes for a series of talks at the Hausdorff Mathematical Institute, Bonn, Oct. 1-11, 2012 December 5, 2012 Contents 1. Prologue 7 2. Lecture 1, Monday Oct. 1: Introduction: (2,0) Theory and Physical Mathematics 7 2.1 Quantum Field Theory 8 2.1.1 Extended QFT, defects, and bordism categories 9 2.1.2 Traditional Wilsonian Viewpoint 12 2.2 Compactification, Low Energy Limit, and Reduction 13 2.3 Relations between theories 15 3. Background material on superconformal and super-Poincar´ealgebras 18 3.1 Why study these? 18 3.2 Poincar´eand conformal symmetry 18 3.3 Super-Poincar´ealgebras 19 3.4 Superconformal algebras 20 3.5 Six-dimensional superconformal algebras 21 3.5.1 Some group theory 21 3.5.2 The (2, 0) superconformal algebra SC(M1,5|32) 23 3.6 d = 6 (2, 0) super-Poincar´e SP(M1,5|16) and the central charge extensions 24 3.7 Compactification and preserved supersymmetries 25 3.7.1 Emergent symmetries 26 3.7.2 Partial Topological Twisting 26 3.7.3 Embedded Four-dimensional = 2 algebras and defects 28 N 3.8 Unitary Representations of the (2, 0) algebra 29 3.9 List of topological twists of the (2, 0) algebra 29 4. Four-dimensional BPS States and (primitive) Wall-Crossing 30 4.1 The d = 4, = 2 super-Poincar´ealgebra SP(M1,3|8). 30 N 4.2 BPS particle representations of four-dimensional = 2 superpoincar´eal- N gebras 31 4.2.1 Particle representations 31 4.2.2 The half-hypermultiplet 33 4.2.3 Long representations 34 -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II “WE ARE ALL ISLANDERS TO BEGIN WITH”: THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AND THE WORLD IN THE LATE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER XVIIEDUCATION XVII THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Hermann von Holst, oil portrait by Karl Marr, 1903 I I “WE ARE ALL ISLANDERS TO BEGIN WITH”: The University of Chicago and the World in the Late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries INTRODUCTION he academic year 2007–08 has begun much like last year: our first-year class is once again the largest in T our history, with over 1,380 new students, and as a result we have the highest Autumn Quarter enroll- ment in our history at approximately 4,900. We can be proud of the achievements and the competitiveness of our entering class, and I have no doubt that their admirable test scores, class ranks, and high school grade point averages will show their real meaning for us in the energy, intelligence, and dedication with which our new students approach their academic work and their community lives in the College. I have already received many reports from colleagues teaching first-year humanities general education sections about how bright, dedicated, and energetic our newest students are. To the extent that we can continue to recruit these kinds of superb students, the longer-term future of the College is bright indeed. We can also be very proud of our most recent graduating class. The Class of 2007 won a record number of Fulbright grants — a fact that I will return to in a few moments — but members of the class were rec- ognized in other ways as well, including seven Medical Scientist Training This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 30, 2007. -

Felix Klein and His Erlanger Programm D

WDS'07 Proceedings of Contributed Papers, Part I, 251–256, 2007. ISBN 978-80-7378-023-4 © MATFYZPRESS Felix Klein and his Erlanger Programm D. Trkovsk´a Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Prague, Czech Republic. Abstract. The present paper is dedicated to Felix Klein (1849–1925), one of the leading German mathematicians in the second half of the 19th century. It gives a brief account of his professional life. Some of his activities connected with the reform of mathematics teaching at German schools are mentioned as well. In the following text, we describe fundamental ideas of his Erlanger Programm in more detail. References containing selected papers relevant to this theme are attached. Introduction The Erlanger Programm plays an important role in the development of mathematics in the 19th century. It is the title of Klein’s famous lecture Vergleichende Betrachtungen ¨uber neuere geometrische Forschungen [A Comparative Review of Recent Researches in Geometry] which was presented on the occasion of his admission as a professor at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Erlangen in October 1872. In this lecture, Felix Klein elucidated the importance of the term group for the classification of various geometries and presented his unified way of looking at various geometries. Klein’s basic idea is that each geometry can be characterized by a group of transformations which preserve elementary properties of the given geometry. Professional Life of Felix Klein Felix Klein was born on April 25, 1849 in D¨usseldorf,Prussia. Having finished his study at the grammar school in D¨usseldorf,he entered the University of Bonn in 1865 to study natural sciences. -

List of Members

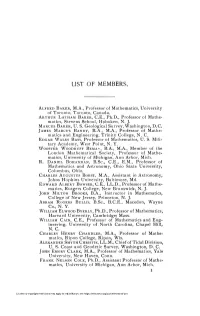

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Evolution of Mathematics: a Brief Sketch

Open Access Journal of Mathematical and Theoretical Physics Mini Review Open Access Evolution of mathematics: a brief sketch Ancient beginnings: numbers and figures Volume 1 Issue 6 - 2018 It is no exaggeration that Mathematics is ubiquitously Sujit K Bose present in our everyday life, be it in our school, play ground, SN Bose National Center for Basic Sciences, Kolkata mobile number and so on. But was that the case in prehistoric times, before the dawn of civilization? Necessity is the mother Correspondence: Sujit K Bose, Professor of Mathematics (retired), SN Bose National Center for Basic Sciences, Kolkata, of invenp tion or discovery and evolution in this case. So India, Email mathematical concepts must have been seen through or created by those who could, and use that to derive benefit from the Received: October 12, 2018 | Published: December 18, 2018 discovery. The creative process of discovery and later putting that to use must have been arduous and slow. I try to look back from my limited Indian perspective, and reflect up on what might have been the course taken up by mathematics during 10, 11, 12, 13, etc., giving place value to each digit. The barrier the long journey, since ancient times. of writing very large numbers was thus broken. For instance, the numbers mentioned in Yajur Veda could easily be represented A very early method necessitated for counting of objects as Dasha 10, Shata (102), Sahsra (103), Ayuta (104), Niuta (enumeration) was the Tally Marks used in the late Stone Age. In (105), Prayuta (106), ArA bud (107), Nyarbud (108), Samudra some parts of Europe, Africa and Australia the system consisted (109), Madhya (1010), Anta (1011) and Parartha (1012). -

Henry Andrews Bumstead 1870-1920

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XIII SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF HENRY ANDREWS BUMSTEAD 1870-1920 BY LEIGH PAGE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1929 HENRY ANDREWS BUMSTEAD BY LIUGH PAGE Henry Andrews Bumstead was born in the small town of Pekin, Illinois, on March 12th, 1870, son of Samuel Josiah Bumstead and Sarah Ellen Seiwell. His father, who was a physician of considerable local prominence, had graduated from the medical school in Philadelphia and was one of the first American students of medicine to go to Vienna to complete his studies. While the family was in Vienna, Bumstead, then a child three years of age, learned to speak German as fluently as he spoke English, an accomplishment which was to prove valuable to him in his subsequent career. Bumstead was descended from an old New England family which traces its origin to Thomas Bumstead, a native of Eng- land, who settled in Boston, Massachusetts, about 1640. Many of his ancestors were engaged in the professions, his paternal grandfather, the Reverend Samuel Andrews Bumstead, being a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary and a minister in active service. From them he inherited a keen mind and an unusually retentive memory. It is related that long before he had learned to read, his Sunday school teacher surprised his mother by complimenting her on the ease with which her son had rendered the Sunday lesson. It turned out that his mother made a habit of reading the lesson to Bumstead before he left for school, and the child's remarkable performance there was due to his ability to hold in his memory every word of the lesson after hearing it read to him a single time. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

The History of the Abel Prize and the Honorary Abel Prize the History of the Abel Prize

The History of the Abel Prize and the Honorary Abel Prize The History of the Abel Prize Arild Stubhaug On the bicentennial of Niels Henrik Abel’s birth in 2002, the Norwegian Govern- ment decided to establish a memorial fund of NOK 200 million. The chief purpose of the fund was to lay the financial groundwork for an annual international prize of NOK 6 million to one or more mathematicians for outstanding scientific work. The prize was awarded for the first time in 2003. That is the history in brief of the Abel Prize as we know it today. Behind this government decision to commemorate and honor the country’s great mathematician, however, lies a more than hundred year old wish and a short and intense period of activity. Volumes of Abel’s collected works were published in 1839 and 1881. The first was edited by Bernt Michael Holmboe (Abel’s teacher), the second by Sophus Lie and Ludvig Sylow. Both editions were paid for with public funds and published to honor the famous scientist. The first time that there was a discussion in a broader context about honoring Niels Henrik Abel’s memory, was at the meeting of Scan- dinavian natural scientists in Norway’s capital in 1886. These meetings of natural scientists, which were held alternately in each of the Scandinavian capitals (with the exception of the very first meeting in 1839, which took place in Gothenburg, Swe- den), were the most important fora for Scandinavian natural scientists. The meeting in 1886 in Oslo (called Christiania at the time) was the 13th in the series. -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D. -

The “Geometrical Equations:” Forgotten Premises of Felix Klein's

The “Geometrical Equations:” Forgotten Premises of Felix Klein’s Erlanger Programm François Lê October 2013 Abstract Felix Klein’s Erlanger Programm (1872) has been extensively studied by historians. If the early geometrical works in Klein’s career are now well-known, his links to the theory of algebraic equations before 1872 remain only evoked in the historiography. The aim of this paper is precisely to study this algebraic background, centered around particular equations arising from geometry, and participating on the elaboration of the Erlanger Programm. An- other result of the investigation is to complete the historiography of the theory of general algebraic equations, in which those “geometrical equations” do not appear. 1 Introduction Felix Klein’s Erlanger Programm1 is one of those famous mathematical works that are often invoked by current mathematicians, most of the time in a condensed and modernized form: doing geometry comes down to studying (transformation) group actions on various sets, while taking particular care of invariant objects.2 As rough and anachronistic this description may be, it does represent Klein’s motto to praise the importance of transformation groups and their invariants to unify and classify geometries. The Erlanger Programm has been abundantly studied by historians.3 In particular, [Hawkins 1984] questioned the commonly believed revolutionary character of the Programm, giving evi- dence of both a relative ignorance of it by mathematicians from its date of publication (1872) to 1890 and the importance of Sophus Lie’s ideas4 about continuous transformations for its elabora- tion. These ideas are only a part of the many facets of the Programm’s geometrical background of which other parts (non-Euclidean geometries, line geometry) have been studied in detail in [Rowe 1989b].