Recovery of the Hawaiian Monk Seal (Monachus Schauinslandi): a Review of Conservation Efforts, 1972 to 2010, and Thoughts for the Future Lloyd F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Style and Ascetics: Attractiveness, Power and the Thai Sangha

Style and Ascetics: Attractiveness, Power and the Thai Sangha Natayada na Songkhla School of Oriental and African Studies Ph.D. Thesis ProQuest Number: 11015841 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is d ep en d en t upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely even t that the author did not send a com p lete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be rem oved, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015841 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Abstract The majority of research for this thesis took place during the Thai general election of 1988 when the new religious movements Santi Asoke and Wat Dhammakaya were subject to investigation for political activity despite, respectively, defiance or denial. The relationship between the Thai Sangha and lay devotees is examined in order to discover how it is that Thai monks, whom many researchers find powerless, can be accused of political activity. In the past, monks have been used to legitimate lay political leaders and have taken active roles in local leadership. This thesis aims to determine whether monks in Thailand have power and, if they do, how such power becomes politically threatening to the status quo. -

How Burnt Are You? Too Many Exams, Too Many Classes,Too M Any, Too M Uch, Too Late Ell, It’S That Time of the Year Again

University of Bridgeport VoL 2, No. 14 December 16, 1982 25 C e n ts How Burnt Are You? Too many exams, too many classes,too m any, too m uch, too late ell, it’s that time of the year again. SCORING KEY 11. feel bored? No, I’m not just ta lk in g about Christ O ften -2 12. “need a drink” at the end of the day? W m as! I ’m ta lk in g about finals! It’s ac Sometimes-1 13. feel as though what you do makes no tually here, the end of the 1982 fall semes N ever-0 difference? ter, and you are probably really burnt out 14. get more satisfaction from work than either from studying or a little too much par D o Y o u : from personal life? tying. But whatever the situation may be, 1. feel tired most of the time? 15. feel stale and uncreative in your work? the results are still the same. 2. smoke more? 16. give up on reading the professional W ell, at the Scribe we decided to give you 3. over or under-eat? literature? another test. Don’t worry, you won’t have to 4. suffer from frequent colds? 17. need more sleep than usual? pull any all-nighters to do this one. This test 5. “have to have’’ 3 or more cups of coffee to 18. have trouble sleeping? is called the Burn-out checklist. It was given get moving in the morning? 19. have difficulty concentrating when at an RA inservice meeting. -

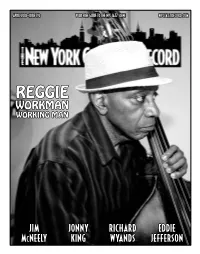

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ART FARMER NEA Jazz Master (1999) Interviewee: Art Farmer (August 21, 1928 – October 4, 1999) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown Dates: June 29-30, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 96 pp. Brown: Today is June 29, 1995. This is the Jazz Oral History Program interview for the Smithsonian Institution with Art Farmer in one of his homes, at least his New York based apartment, conducted by Anthony Brown. Mr. Farmer, if I can call you Art, would you please state your full name? Farmer: My full name is Arthur Stewart Farmer. Brown: And your date and place of birth? Farmer: The date of birth is August 21, 1928, and I was born in a town called Council Bluffs, Iowa. Brown: What is that near? Farmer: It across the Mississippi River from Omaha. It’s like a suburb of Omaha. Brown: Do you know the circumstances that brought your family there? Farmer: No idea. In fact, when my brother and I were four years old, we moved Arizona. Brown: Could you talk about Addison please? Farmer: Addison, yes well, we were twin brothers. I was born one hour in front of him, and he was larger than me, a bit. And we were very close. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Brown: So, you were fraternal twins? As opposed to identical twins? Farmer: Yes. Right. -

New World NW 271 Jazz Historians Explain the Coming of Bebop—The Radically New Jazz Style That Established Itself Toward

Bebop New World NW 271 Jazz historians explain the coming of bebop—the radically new jazz style that established itself toward the end of World War II—as a revolutionary phenomenon. The motives ascribed to the young pioneers in the style range from dissatisfaction with the restrictions on freedom of expression imposed by the then dominant big-band swing style to the deliberate invention of a subtle and mystifying manner of playing that could not be copied by uninitiated musicians. It has even been suggested that bebop was invented by black musicians to prevent whites from stealing their music, as had been the case with earlier jazz styles. Yet when Dizzy Gillespie, one of the two chief architects of the new style, was asked some thirty years after the fact if he had been a conscious revolutionary when bebop began, his answer was Not necessarily revolutionary, but evolutionary. We didn't know what it was going to evolve into, but we knew we had something that was a little different. We were aware of the fact that we had a new concept of the music, if by no other means than the enmity of the [older] musicians who didn't want to go through a change.... But it wasn't the idea of trying to revolutionize, but only trying to see yourself, to get within yourself. And if somebody copied it, okay! Were he able, the other great seminal figure of bebop, alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, would probably amplify Gillespie's opinion that the new music arose from inner needs rather than external factors. -

Download (12Mb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36376 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. LONE OR ALONE? A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF LONE MOTHERS ON LOW INCOME WITH REFERENCE TO SUPPORT IN THEIR EVERYDAY LIVES By Josephine Patricia Dearlove BA (Hons) Sociology / Social Policy Thesis submitted for the qualification of PhD University of Warwick Department of Social Policy and Social Work March 1999 ABSTRACT The thesis invites women to voice their perceptions and experiences on being lone mothers, in receipt of Income Support and what 'support' means to them in their daily lives as carers of pre-school children. This qualitative study is set against firstly, the backdrop of the increasing numbers of lone mothers and their reliance on income support. Also prevalent was a negative discourse around lone motherhood. Secondly, lone mothers were encountering the consequences of a restructuring of social and welfare policy and practice, with the changing boundaries between public and private responsibilities impacting on their daily lives. Thirdly, within this changing socio-economic and political landscape, both neo-liberal and 'third way' governments identify kinship as the appropriate resource for families in need. The study draws data and analysis from the perceptions and experiences of, initially, thirty-three women in five focus groups and more particularly, from thirty- seven lone mothers on Income Support. -

The Upright Bass DAN RAPHAEL “And Never Again Arrives” Light Hurts

KAHL • MOORE • VIZENOR • HASTAIN • HOUSTMAN GONZALEZ • LUCAS • COTTER • ARGÜELLES • DUCHARME KALAMARAS • STEWARD • BEINING • BARNES • VON GERALDO LOTTI • VANDER MOLEN • VEGA • BENNETT • HOGAN • ABBOTT LEVINSON • SMITH • ZVER • GRABILL • HAUPTMAN • RAPHAEL Cover: WELCOME ABROAD by Brian Lucas, 2017 acrylic and oil pen on canvas (30” x 24”) Cover and title page design by Gary R. Smith, 1986 Typeset in Baskerville by Daniel Estrada Del Cid, HS Marketing Solutions, Westminster, California Lawrence R. Smith, Editor Deanne C. Smith, Associate Editor Daniel Estrada Del Cid, Production and Design Editor Calibanonline is published quarterly. Viewing online and pdf downloads are free. Unsolicited poetry, fiction, art, music, and short art videos welcome. Please direct attached WORD documents to [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS TIM KAHL The Secretary of the Future Validating Turbulence ELLENE GLENN MOORE Hand Mirror in Bronze Seeing a Study for The Burghers of Calais at a Museum in Cleveland JIM ZVER Hallucination.24 JAMES GRABILL She Rings Up J J HASTAIN ( DALE HOUSTMAN In a Corner Madame Finance RAY GONZALEZ Sadness Leonora Carrington, British 1917-2011, Portrait of Max Ernst, 1929. Published in View 2, Number one, 1942. Oil on canvas. 19 ¾ by 10 ½. Private Collection. Bead Thrive Dark Star The Hippie BRIAN LUCAS The Old Weird The Internal Program That Leads One Astray World Feasting Dawn Moment CRAIG COTTER Michigan Wildflowers GERALD VIZENOR Satie on the Seine INES VEGA Nadando en la Mañana El Delfin Navegando Las Alas GEORGE KALAMARAS Turiya and Ramakrishna Forrest Fire The Belt of Equatorial Calms More Monk Than Mouth Where the Stinging Might Sing D.E. -

Make a True Home of Your Love Monastic Life

Summer 2011 A Publication of Plum Village Issue 57 $8/€8/£6 Make a True Home of Your Love By Thich Nhat Hanh Monastic Life w the european InstItute of applIed BuddhIsm A few courses we will be offering in Fall 2011, Waldbrol, Germany July 15-17 Sept 23-30 October 14-21 A Retreat on Interreligious Wake Up Retreat on Deep Ecology, Looking deeply into our eating. ZenDialogue in the with European Prof. Dr. ContextMichael von Brück forThe ages World 16-30. We Are With the Dharma WithEating Sr. and Ingrid Emotions (Bi Nghiem) and Teachers of the EIAB. Sr. Jewel (Chau Nghiem) Aug 25-28 Sept 30-Oct 2 October 20-23 For those who lead a Sangha and for BeingAspirants a Good of the Spiritual Order of FriendInterbeing, with Sr. Annabel (True Virtue) Course with Br. Phap Xa withReconciliation Dr. Helmut and Wetzel, Healing from Simply Enjoy Sitting Sept 8-11 Dr.Violence Tom Holmesin Times and of War Br. Phap An Oct 21-28 The basics of a global economic ethic October 7-14 Course with Dharma teachers Weinspired are theby Buddhism. Economy A Course with ofMindful the EIAB Communication Dr. Kai Romhardt Course 3F with Dharma teachers ofMindfulness EIAB Practice for Artists For more information and registration: www.eiab.eu OR [email protected] OR 49 2291 907 1373 2010 Retreats with Thich Nhat Hanh • 4/6/2011 MINDFULNESS BELL: 1/2 PAGE AD • 7.25” (w) x 4.375” (h) • (no bleed) • GREYSCALE FINAL MECHANICAL Contact: Steve Child Design (323)420-6907 ISSUE NO. -

Fall 2002 1 T Able of Contents

E DITORIAL NOTE National Center for Education Statistics The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) fulfills a congressional mandate to collect and report “statistics and information showing the con- dition and progress of education in the United States and other nations in order to promote and accelerate the improvement of American education.” EDUCATION STATISTICS QUARTERLY Purpose and goals At NCES, we are convinced that good data lead to good decisions about education. The Education Statistics Quarterly is part of an overall effort to make reliable data more accessible. Goals include providing a quick way to ■ identify information of interest; ■ review key facts, figures, and summary information; and ■ obtain references to detailed data and analyses. Content The Quarterly gives a comprehensive overview of work done across all parts of NCES. Each issue includes short publications, summaries, and descriptions that cover all NCES publications and data products released during a 3-month period. To further stimulate ideas and discussion, each issue also incorporates ■ a message from NCES on an important and timely subject in education statistics; and ■ a featured topic of enduring importance with invited commentary. A complete annual index of NCES publications appears in the Winter issue (published each January). Publications in the Quarterly have been technically reviewed for content and statistical accuracy. General note about the data and interpretations Many NCES publications present data that are based nonsampling errors. In the design, conduct, and on representative samples and thus are subject to data processing of NCES surveys, efforts are made to sampling variability. In these cases, tests for statistical minimize the effects of nonsampling errors, such as significance take both the study design and the number item nonresponse, measurement error, data processing of comparisons into account. -

Sb2559 Testimony Ene 02-02

S82559 WRITTEN TESTIMONY ONLY UNDAL1NGLE CHlYOME lEINAAlA FUKlNO, M.D. GOVERNOR OF HAWAU DIRECTOR OF HEALTH STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH P.O.80x3378 In reply, please refer 10: HONOLULU, HAWAII 96801-3378 File: COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT S.B. 2559, RELATING TO ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Testimony of Chiyome Leinaala Fnkino, M.D. Director of Health Febrnary 2, 2010 3:30 p.m. Department's Position: The Department of Health opposes this bill as written because of the added 2 burdens it imposes on the department. 3 Fiscal Implications: The bill imposes substantial administrative duties on the department without new 4 resources. The amount of added cost is uncertain, but added costs will occur. 5 Pnrpose and Justification: Effective January 1,2012, this bill bans the distribution to customers of 6 non-biodegradable single-use plastic checkout bags by businesses with annual gross sales over 7 $300,000. 8 DOH generally supports the reduction of solid waste, litter, and the use of petroleum resources. 9 State policy already sets source reduction and recycling as the top two priorities for solid waste 10 management (HRS §342G-2(b». We favor reducing plastic marine pollution because of its effect on I I wildlife. 12 The bill adds significant administrative functions to the DOH without adding any resources to 13 manage them. DOH will have to enforce the law at many businesses in the state, with no new staff or 14 other resources. DOH will also have to rule on claims by businesses to be exempt because of hardship S.B.2559 Page 2 of2 conditions. -

LINER NOTES Thelonious Monk Live at Palo Alto High School in the Fall

LINER NOTES Thelonious Monk Live at Palo Alto High School In the fall of 1968, a sixteen-year-old Jewish kid named Danny Scher had a dream. He wanted to bring the renowned Thelonious Monk and his quartet to play a benefit concert at his high school in Palo Alto, California. Armed with little more than a telephone, posters, a persuasive pitch, an impressive knowledge of jazz, and iron-willed determination, Scher not only made it happen but temporarily united a divided city. As Scher makes clear in his own notes, the kid was no neophyte. Born on October 19, 1951, his conversion to jazz began at age ten. A few years later, he was putting up posters and doing odd jobs for the legendary Bay Area jazz promoter Darlene Chan and critic Ralph Gleason. His classmates at Palo Alto High School all knew Danny as the red-headed kid who spun jazz records every Wednesday at lunch time for anyone willing to listen. During his junior year (1967-68), Scher was elected chairman of the campus International Club, and in an effort to raise money for the Peace Corps and school construction projects in Kenya and Peru, he organized jazz concerts. In December he produced an afternoon concert featuring pianist Vince Guaraldi and vocalist Jon Hendricks, followed by vibraphonist Cal Tjader and his quintet in April. Now entering his senior year, he had his sights on Monk and possibly Duke Ellington. Darlene Chan had him call Monk’s manager, Jules Colomby. Jules quoted a fee of $500 and agreed to the gig, but never followed up with a fully executed contract.