The Rites of Longing Tommy Chisholm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chancellor Search Quietly Continues

INDEPENDENT SINCE 1956 INSIDE NEWS The The Aldermanic race and UWM UWM PAGE 3 EDITORIAL Dean blows the Iowa caucus January 28, 2004 The weekly campus newspaper of UWM Volume 48 | Issue 16 PAGE 25 UWM Dance Team wins NEWS Hip Hop Championships The SA Spotlight: Know what's PAGE 8 going on at UWM! PAGE 2 Men's Basketball hits SPORTS eight conference wins What you missed in UWM PAGE 18 athletics PAGES 18-19 Greenstreet to Veto override sent to Assembly Governor Doyle re-examines Conceal and Carry Bill continue progress very surprised that the veto was overridden," said Carpen ter. "I hold no ill will but I in plenary address think it was a terrible deci sion. By Nathan Hal! "It is one of the worst pieces Staff Writer of legislation I have seen writ ten in the last 20 years. It has The spring semester plenary a lot of flaws," said Carpenter. speech, titled "Building Bridges, Some Bill supporters are Laying Foundations—A Progress confident that the Assembly Report," was held on Thursday, will uphold the veto override; Jan. 22 in Bolton Hall. Interim others say it will be close. Chancellor Bob Greenstreet and "I think it will be a close call Provost/ Vice Chancellor for Aca in the assembly," said Rolf Lind- demic Affairs John Wanat gave gren the author of a brief report on the state of the recalldoyle.com. "I think it will university to an audience of come down to one vote." approximately 150 people, Carpenter agreed with Lind- including administrators, facul Greenstreet gren. -

Meditative Story Transcript – Kaywin Feldman

Meditative Story Transcript – Kaywin Feldman Click here to listen to the full Meditative Story episode with Kaywin Feldman. KAYWIN FELDMAN: I don’t even change my clothes. I just head out to make it there in time. It’s close to the center of town, so I don’t have to walk far. I pay my entrance fee and walk in. There are hardly any visitors. The chapel is small and attached to a monastery. The building itself is tall but nothing terribly special. But suddenly I see it: Every inch of wall, floor to ceiling, is painted with a narrative cycle. The first thing I notice is the stillness. I can’t even hear my sneakers on the stone floor. It’s cool inside. Then the glow. The whole room, even the arched ceiling, glows lapis blue from the paint. Inside this still room, my body stills, too. I am in need of sanctuary, and here it is. It feels safe, sacred. It lets me emotionally and intellectually clear my mind, so that I can really look at the frescoes. I’m hardly breathing. My heart rate slows. I can feel my mouth open as I take in the room. ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Kaywin Feldman grew up in a military family, and her childhood memories are dominated by visits to art museums in the various cities and towns where her family moved. You might say she was destined to become a museum director, and at the young age of 28, she achieves just that. Today, Kaywin presides over the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Ikebe Shakedown: Ikebe Shakedown for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 06/07/2011

UBIQUITY RECORDS PRESENTS IKEBE SHAKEDOWN: IKEBE SHAKEDOWN FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 06/07/2011 Jed and Lucia HELIUM EP Ikebe Shakedown, the self-titled album from the more like a larger ensemble as increasing layers leap from the tapes. At the other end of the BPM counter, on “Tujunga,” the Brooklyn-based band, plays with elements of band build a gritty African disco jam boasting a floor-filling Cinematic Soul, Afro-funk, Deep Disco, and percussion section, adding seductive guitar licks and an irresistible bass-line to set their horns ablaze. “Tame The Beats” Boogaloo in all the right ways. After spending a is pure fire - bold melodies and heavy rhythms propel the song, few years together the group, named after a with Meters-esque breakdowns providing only brief respite from favorite Nigerian boogie record (and pronounced the action. “ee-KAY-bay,”) delivers a driving set of tunes Some upcoming shows for the band include: May 20th - 7 Inch Release Party - Sullivan Hall, NYC featuring a mighty horn section anchored by tight, June 2nd - Music Frees All Festival - Webster Hall, NYC deep-pocketed grooves. June 3rd - Burlington Jazz Festival - Red Square, Burlington, VT June 9th - Record Release Party - Southpaw, Brooklyn, NY “Right now in cities across the globe, there are plenty of great Afrobeat July 1st - Cornell College - Ithaca, NY revivalist bands aping the sound and groove of Fela Kuti’s legendary sound. July 2nd - Keegan Ales - Kingston, NY Yet, surprisingly few of the new groups have strayed from an orthodox interpretation of the genre or done much real innovation. -

Dateline:Downtown Volume 61 Issue 3 October 23, 2018

University of Houston-Downtown’s Newspaper Student Run Since Volume One Dateline:downtown Volume 61 Issue 3 October 23, 2018 In this issue Local band with a common News ...........................................................................pg 3 bond on the rise.....pg 6 College Life ...............................................................pg 4 Arts and Entertainment .........................................pg 7 Columns .....................................................................pg 11 2 Staff From the editor’s desk Editor Quintin Coleman by Quintin Coleman for Less, a column that gives a look at restaurants around the UHD area that of- Assistant Editor fer student friendly deals and are budget Hello Gators and welcome back to Date- Michael Case friendly to students as well, along with line: Downtown. It’s been a little while our first faculty column writer Adam since you’ve seen the paper on the stands Ellwanger, the director of the Master’s Business Manager around campus but we are back and of Rhetoric and Composition graduate better than ever. Before I go into what program here at UHD. He’s not afraid to Irene Nunez is coming up in this issue, I want to say go into a hot button issue so his thoughts thanks to the staff who have worked with are definitely worth the read. me during the first two issues of the pa- Social Media Manager There’s plenty more that this per during my tenure and the supporters issue offers but I can’t give everything who picked up the paper. Whether it was Sonia Sanchez away in the first full page. You’re just because of the content of the paper or the going to have to see what else is in stellar art design from Brenda Valenzue- store in this issue. -

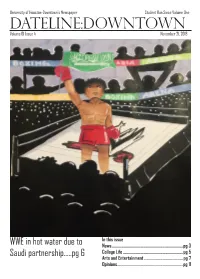

Dateline Downtown Volume 61 Issue 4

University of Houston-Downtown’s Newspaper Student Run Since Volume One Dateline:downtown Volume 61 Issue 4 November 21, 2018 In this issue WWE in hot water due to News ...........................................................................pg 3 Saudi partnership.....pg 6 College Life ...............................................................pg 5 Arts and Entertainment ......................................... pg 7 Opinions .....................................................................pg 11 2 Staff From the editor’s desk Editor Quintin Coleman a musical. This may be a high-minded and idealistic take but perhaps it’s worth Assistant Editor keeping in mind that hard work may very Michael Case well take you further than you imagined. It’s impossible to quantify someone’s lifelong career (especially Business Manager given that the man in question died at 95) into a space of about 550 words. Irene Nunez It’s also impossible for me to go into a heartfelt tribute as I wasn’t a diehard fan Social Media Manager of Marvel growing up. What I can say, however, is that he did so much for so Sonia Sanchez many people in so many contexts. He was someone who did something rare for his time: he wrote material that appealed Faculty Advisor to children but could appeal to adults at the same time (if adults took a critical Joe Sample, PhD Photo courtesy of LBC9 News knew and loved. He even created his own look at those comics anyway.) His world company after leaving Marvel yet still re- became so large that it essentially formed tained his status as an ambassador for the Staff Writers the childhood of children for past genera- On November 12, the world lost a leg- company. -

Download the Transcript

SPI Podcast Session #46 – Building a Lucrative Business with No Ideas, No Expertise & No Money With Dane Maxwell Show notes at: http://www.smartpassiveincome.com/session46 This is the Smart Passive Income podcast with Pat Flynn, session #46! Alright, you got this one. Announcer: Welcome to the Smart Passive Income podcast, where it's all about working hard now so you can sit back and reap the benefits later. And now your host; he was born in Connecticut and for some crazy reason, he misses the winter, Pat Flynn! Pat: Sometimes. Sometimes I miss the winter. I mean, 75 all year long is great, but sometimes you've just got to mix it up, which is exactly what we're going to do today. My name is Pat Flynn, welcome to session 46 of the Smart Passive Income Podcast. I'm super-stoked to be hanging out with you today, so let's get right into today's content! Like I said, we're mixing things up today because we're bringing on a guest who approaches online business a little differently than most people do, at least here in the solopreneur space. A lot of people who teach this online business stuff, including myself, talk about picking a topic of interest, preferably something you're passionate about or at least are very interested in, and then becoming an expert at it and sharing that knowledge with others who would consider you an expert just because you know a little bit more than they do. And really, that's all it takes to become an expert. -

Virginia Harmony

November 1, 2018 Volume 1, Issue 2 Virginia Harmony President’s Message: Community I am thinking about COMMUNITY these days, and how choir creates, explores, and sustains community. In my beginning conducting class, we talk a lot about the role of the conductor as a leader in the community. We create community within our ensembles, but we function within a larger community. How do we connect with the people around us? If you are new to your job, you dig in to your choral library to see what’s there, but you also have to dig in to your community. Who are the people around you? What excites them, unites them? How can you connect to them? Inside this issue Farmville was hit hard by Tropical Storm Michael as it regained strength on its way back out to sea. Power was Constitution and By-laws .................... .2 out from Thursday afternoon until Tuesday for many of us. Sunday morning, my singers were there–many still without power–to sing together for worship. They sing because they love to sing, but they also sing because we are community, and we bring community to those who come to worship. VMEA & VCDA...……………………....3 At Longwood, we still do a Holiday Dinner. Multiple ensembles perform as our guests and are served various President-Elect Candidates…..………..4 courses. People wear red and green; we have instrumental and vocal carolers as people find their way into the venue. In many areas I would not be called upon to create music for a holiday event; in some areas I would be Events Calendar .................................. -

2019 Song School Monday

The Song School August 11-15, 2019 • Lyons, CO Schedule and Course Descriptions Sunday, August 11th TO DO LIST: ● Sign up for open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime on Monday in the Blue Heron Tent. (Registration Tent) ● Check master roster information at registration desk for accuracy. 1:00 Campgrounds Opens 2:00 - 5:00 Student Registration Visit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, official Song School laminate, reusables, biobag for compostables and other goodies. 5:30 - 6:00 New Student Meet and Greet - Wildflower Pavilion First timer? Meet up with Song School veterans, an instructor or two, ask that burning question, and get some sage advice on how to make your week enjoyable. “Eighty percent of life is just showing up.” – Woody Allen Monday, August 12th TO DO LIST: ● Sign up by 9:15am for open stage lottery. All schedules will be posted during lunchtime in the Blue Heron Tent. ● Check master roster information at registration desk for accuracy. ● Mentoring sheets will go out at 9am each morning for that day’s mentoring sessions. 8:00 - 9:15 Student Registration Visit us at the Blue Heron Tent and pick up your Song School schedule, wristband, official Song School laminate, reusables, biobag for compostables and other goodies. Help yourself to tea or coffee and fruit and pastries next door at the beverage area. Burritos and snacks available at Bloomberries Booth next to bathhouse. Monday p. 2 8:00 - 9:00 Yoga Yogi Heather Hottovy will help celebrate the start of your day with a gentle yoga routine each morning. -

OSA-AMP-2007-06.Pdf (4.970Mb)

Office of Student Affairs 2007-5-01 A Modest Proposal, vol. 3, no. 8 Kimberly Allen, et al. © 2007 A Modest Proposal Find more information about this article here. This document has been made available for free and open access by the Eugene McDermott Library. Contact [email protected] for further information. T H E E UTO STUDE N T PUBLICATION Mindless Markllp· Waterview tenants pay for Utley's greed page 4 ~·--- INSID E The Trinity River Project scandaJ to the courtroom Dallas's Central Park vision page 8 ~-~~~ is becoming a reality page 16 S UMMER 2007 • VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 8 AMP.UTDALLAS.EDU 2 CoNTENTS SUMM ER 20 07 • Vo LuMe 3 • Issu e 8 In 1his Issue. • • AR TS & L EISURE E DITORs' Buzz Student Government's Failure 12 Listening for the Summer 3 The closed SG meeting opposes the central An overview of the hottest albums responsibility of the organization. and concerts coming this summer EDITORIAL BY JORDAN YOUNGBLOO Editors Fatty J's Picks Kimberley Allen Summer selections for food Liam Skoyles C A M PU S LIFE near campus. Benedict Voit BY JAMES FICKENSCHER Jordan Youngblood Millionaire's Payday 4 A continued in-depth investigation into the Utley Foundation's financial history. S ociAL CoMM ENTARY BY KIM ALLEN I 5 Rooting for the Underdog 6 No Vacancy Knowing the odds were against you Contributors can help make the not-so-sunny Why there is a desperate need to overhaul (create?) results a little more satisfying. a UTD system of reserving rooms on campus. Richard Badgett BY JONATHAN LANE BY LIAM SKOYLES Charlie Cliff Jonathan Coker Working to Avoid Work 16 A Bridge to the Future Ben Dower 7 The Trinity Trust Project is a bold James Fickenscher Fun ways to waste that oh-so-precious time. -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles -

Voices in Real Time Interactive and Transmedia Testimonies of the Arab Spring, Instant Archive and New Social Movements Discourses

International PHD Programme in Audiovisual Studies University of Udine, DAMS Gorizia a.a.20 !"20 # Voices in real time Interactive and transmedia testimonies of the Arab Spring, instant archive and new social movements discourses $andidate% &udovica Fales Su)ervisors% *oy Menarini, University of Bologna Ian C,ristie, Bir-.e'- College London 1 /The wor- of our time is to clarify to itself t,e meaning of its o1n desires' 2. Mar3, 'For a Rut,less Criticism of Everyt,ing E3isting' (16!!7 1 2. Mar3, /(or a *ut,less $riticism of 4veryt,ing 43isting,/ in Te Marx- ngles !eader, ed *obert $. 8u'-er, 2nd edition, Ne1 Yor-, W.;. Norton, p. <=6, 12> # 2 I9D4? Introduction "e#ning the research field : transmedia or interactive documentaries% &owards a de#nition of interactive documentaries as '(living( entities )h* is this useful in relation to Tahrir S+uare? xploring the research field. What actions and whose voices% Than-s $,a)ter I – "ocumenting events in the ma-ing toda* 1.1. Documenting collective events in their actuality. A Pre-,istory .,.,., Te formation of the modern public sphere$ actualit* and participation -Te philosophical concept of actualit* - nlightenment as re/ective consciousness on the present -0lashes and fragments of the present time -Actualit* as gathering the present .,.,2 "Te whole world is watching3, Witnessing and showing d*namic in narrating dissent -A new consciousness of news media in the Chicago.567 revolt -"ocumenting and producing media protests (.59:-2::.; - September 1., 2::.. “Te death of detachment( in the news 1.2 Glo.al imagination, actuality, present>tense, real>time .,2,., =lobal imagination, >ocal imagining, A 4ultural Studies &oolbox for Media !epresentation in the =lobal World -=lobal Imagination, Local Imagining -?e*ond '@rientalism'% - Self-narratives, testimonies, micro narratives .,2,2, Te Space of Tahrir S+uare- Within and Without -A Space-in-process -A Space Extended to Tose Watching It -Aerformativit* of Tahrir S+uare - Social Media, Social Change and CitiBen Witnessing – A Faceboo- revolution% .,2,D, Can Tahrir S+uare 2:.