Approach to Diplopia CONTINUUM AUDIO by Christopher C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cranial Nerve Palsy

Cranial Nerve Palsy What is a cranial nerve? Cranial nerves are nerves that lead directly from the brain to parts of our head, face, and trunk. There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves and some are involved in special senses (sight, smell, hearing, taste, feeling) while others control muscles and glands. Which cranial nerves pertain to the eyes? The second cranial nerve is called the optic nerve. It sends visual information from the eye to the brain. The third cranial nerve is called the oculomotor nerve. It is involved with eye movement, eyelid movement, and the function of the pupil and lens inside the eye. The fourth cranial nerve is called the trochlear nerve and the sixth cranial nerve is called the abducens nerve. They each innervate an eye muscle involved in eye movement. The fifth cranial nerve is called the trigeminal nerve. It provides facial touch sensation (including sensation on the eye). What is a cranial nerve palsy? A palsy is a lack of function of a nerve. A cranial nerve palsy may cause a complete or partial weakness or paralysis of the areas served by the affected nerve. In the case of a cranial nerve that has multiple functions (such as the oculomotor nerve), it is possible for a palsy to affect all of the various functions or only some of the functions of that nerve. What are some causes of a cranial nerve palsy? A cranial nerve palsy can occur due to a variety of causes. It can be congenital (present at birth), traumatic, or due to blood vessel disease (hypertension, diabetes, strokes, aneurysms, etc). -

Canine Red Eye Elizabeth Barfield Laminack, DVM; Kathern Myrna, DVM, MS; and Phillip Anthony Moore, DVM, Diplomate ACVO

PEER REVIEWED Clinical Approach to the CANINE RED EYE Elizabeth Barfield Laminack, DVM; Kathern Myrna, DVM, MS; and Phillip Anthony Moore, DVM, Diplomate ACVO he acute red eye is a common clinical challenge for tion of the deep episcleral vessels, and is characterized general practitioners. Redness is the hallmark of by straight and immobile episcleral vessels, which run Tocular inflammation; it is a nonspecific sign related 90° to the limbus. Episcleral injection is an external to a number of underlying diseases and degree of redness sign of intraocular disease, such as anterior uveitis and may not reflect the severity of the ocular problem. glaucoma (Figures 3 and 4). Occasionally, episcleral Proper evaluation of the red eye depends on effective injection may occur in diseases of the sclera, such as and efficient diagnosis of the underlying ocular disease in episcleritis or scleritis.1 order to save the eye’s vision and the eye itself.1,2 • Corneal Neovascularization » Superficial: Long, branching corneal vessels; may be SOURCE OF REDNESS seen with superficial ulcerative (Figure 5) or nonul- The conjunctiva has small, fine, tortuous and movable vessels cerative keratitis (Figure 6) that help distinguish conjunctival inflammation from deeper » Focal deep: Straight, nonbranching corneal vessels; inflammation (see Ocular Redness algorithm, page 16). indicates a deep corneal keratitis • Conjunctival hyperemia presents with redness and » 360° deep: Corneal vessels in a 360° pattern around congestion of the conjunctival blood vessels, making the limbus; should arouse concern that glaucoma or them appear more prominent, and is associated with uveitis (Figure 4) is present1,2 extraocular disease, such as conjunctivitis (Figure 1). -

Strabismus: a Decision Making Approach

Strabismus A Decision Making Approach Gunter K. von Noorden, M.D. Eugene M. Helveston, M.D. Strabismus: A Decision Making Approach Gunter K. von Noorden, M.D. Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics Baylor College of Medicine Houston, Texas Eugene M. Helveston, M.D. Emeritus Professor of Ophthalmology Indiana University School of Medicine Indianapolis, Indiana Published originally in English under the title: Strabismus: A Decision Making Approach. By Gunter K. von Noorden and Eugene M. Helveston Published in 1994 by Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis, MO Copyright held by Gunter K. von Noorden and Eugene M. Helveston All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the authors. Copyright © 2010 Table of Contents Foreword Preface 1.01 Equipment for Examination of the Patient with Strabismus 1.02 History 1.03 Inspection of Patient 1.04 Sequence of Motility Examination 1.05 Does This Baby See? 1.06 Visual Acuity – Methods of Examination 1.07 Visual Acuity Testing in Infants 1.08 Primary versus Secondary Deviation 1.09 Evaluation of Monocular Movements – Ductions 1.10 Evaluation of Binocular Movements – Versions 1.11 Unilaterally Reduced Vision Associated with Orthotropia 1.12 Unilateral Decrease of Visual Acuity Associated with Heterotropia 1.13 Decentered Corneal Light Reflex 1.14 Strabismus – Generic Classification 1.15 Is Latent Strabismus -

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia As a Presenting Feature in a COVID-19-Positive Patient Varshitha Hemanth Vasanthpuram,1 Akshay Badakere 2

Case report BMJ Case Rep: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2021-241873 on 13 April 2021. Downloaded from Internuclear ophthalmoplegia as a presenting feature in a COVID-19- positive patient Varshitha Hemanth Vasanthpuram,1 Akshay Badakere 2 1Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery SUMMARY was unremarkable. His vitals at the time of screening Services, LV Prasad Eye Institute, A 58-year -old man presented with vertical diplopia were 94% saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2), Hyderabad, India temperature of 35.8°C and pulse rate of 91 per 2 for 10 days which was sudden in onset. Extraocular Child Sight Institute, Jasti V movement examination revealed findings suggestive minute. His overall systemic status was stable, with Ramanamma Children’s Eye of internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Investigations were no respiratory symptoms noted. Care Centre, LV Prasad Eye Institute, Hyderabad, India suggestive of diabetes mellitus, and reverse transcription- PCR for SARS-CoV -2 was positive. At 3 weeks of INVESTIGATIONS follow-up , his diplopia had resolved. Neuro-ophthalmic Correspondence to Extraocular motility examination, the abducting manifestations in COVID-19 are increasingly being Dr Akshay Badakere; nystagmus in the left eye and the saccades were akshaybadakere@ gmail.com recognised around the world. Ophthalmoplegia due indicative of INO. Fatigue and ice pack test were to cranial nerve palsy and cerebrovascular accident negative. Initial blood investigations of complete Accepted 26 March 2021 in COVID-19 has been reported. We report a case blood count, lipid profile and 24- hour urine protein of internuclear ophthalmoplegia in a patient with were within normal range. Fasting and postprandial COVID-19. blood sugar levels were 121 mg/dL and 205 mg/dL, respectively, and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 7.5%, suggestive of diabetes mellitus. -

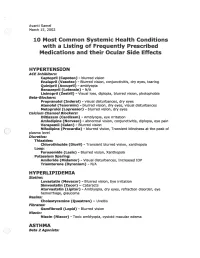

2002 Samel 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with A

Avanti Samel / March 15, 2002 10 Most Common Systemic Health Conditions with a Listing of Frequently Prescribed Medications and their Ocular Side Effects HYPERTENSION ACE Inhibitors: Captopril (Capoten}- blurred vision Enalapril (Vasotec) - Blurred vision, conjunctivitis, dry eyes, tearing Quinipril (Accupril)- amblyopia Benazepril (Lotensin)- N/A Lisinopril (Zestril) - Visual loss, diplopia, blurred vision, photophobia Beta-Blockers: Propranolol (Inderal)- visual disturbances, dry eyes Atenolol (Tenormin)- blurred vision, dry eyes, visual disturbances Metoprolol (Lopressor) - blurred vision, dry eyes calcium Channel Blockers: Diltiazem (Cardizem)- Amblyopia, eye irritation Amlodipine (Norvasc)- abnormal vision, conjunctivitis, diplopia, eye pain Verapamil (Calan)- Blurred vision Nifedipine (Procardia) - blurred vision, Transient blindness at the peak of plasma level · Diuretics: Thiazides: Chlorothiazide (Diuril) - Transient blurred vision, xanthopsia Loop: Furosemide (Lasix) - Blurred vision, Xanthopsia Potassium Sparing: Amiloride (Midamor) - Visual disturbances, Increased lOP Triamterene (Dyrenium)- N/A HYPERLIPIDEMIA Statins: Lovastatin (Mevacor) - Blurred vision, Eye irritation Simvastatin (Zocor)- Cataracts Atorvastatin (Lipitor)- Amblyopia, dry eyes, refraction disorder, eye hemorrhage, glaucoma Resins: Cholestyramine (Questran)- Uveitis Fibrates: Gemfibrozil (Lopid)- Blurred vision Niacin: Niacin (Niacor) - Toxic amblyopia, cystoid macular edema ASTHMA ( ) Beta 2 Agonists: Albuterol (Proventil) - N/A ( Salmeterol (Serevent)- -

Diplopia Evaluation

Diplopia [ ] Monocular (monocular if diplopia present even when only 1 eye open) vs [ ] Binocular (binocular only when both eyes open) Causes If painful, think of the following: Red Flags Monocular diplopia Binocular diplopia usually d/t something usually d/t disconjugate Compressive lesion/tumor/aneurysm >1 cranial nerve deficit distorting light through alignment of eyes eye to retina Sinusitis/abscess/cavernous sinus thrombosis Pupillary involvement cataract CN palsy (3rd, 4th, 6th) corneal shape problems Myasthenia gravis Orbital myositis Other neurologic s/s alongwith diplopia (keratoconus) uncorrected refractive Orbital infiltration (e.g. Trauma (fracture/hematoma) Pain error (usually thyroid infiltrative astigmatism) ophthalmopathy, orbital pseudotumor) Skull base tumors (pain often unrelated to eye movement) Proptosis other: corneal scarring, Other causes: CVA dislocated lens, affecting pons/midbrain; malingering compressive lesion (aneurysm, tumor); History idiopathic; inflammatory/infectious (sinusitis, cavernous sinus monocular vs binocular? gait difficulties (CN 8) thrombosis, abscess); Wernicke’s ; orbital myositis; trauma intermittent or constant? difficulty with bladder control (MS) (fracture, hematoma); tumors near base of skull/sinuses/orbits; images separated horizontally or vertically or a weakness/sensory abnormalities (intermittent or botulism; GBS/Miller- combination of both? constant) Fisher; MS vision changes? (CN2) N/V/diarrhea (botulism) Key points numbness of forehead/face/cheek (CN5) swallowing or speech difficulties -

GAZE and AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1)

GAZE AND AUTONOMIC INNERVATION DISORDERS Eye64 (1) Gaze and Autonomic Innervation Disorders Last updated: May 9, 2019 PUPILLARY SYNDROMES ......................................................................................................................... 1 ANISOCORIA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Benign / Non-neurologic Anisocoria ............................................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Preganglionic .......................................................................... 1 Ocular Parasympathetic Syndrome, Postganglionic ........................................................................ 2 Horner Syndrome ............................................................................................................................. 2 Etiology of Horner syndrome ................................................................................................ 2 Localizing Tests .................................................................................................................... 2 Diagnosis ............................................................................................................................... 3 Flow diagram for workup of anisocoria ........................................................................................... 3 LIGHT-NEAR DISSOCIATION ................................................................................................................. -

Intermittent Mydriasis Associated with Carotid Vascular Occlusion

Eye (2018) 32, 457–459 © 2018 Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature. All rights reserved 0950-222X/18 www.nature.com/eye 1,2 2 2 Intermittent mydriasis PD Chamberlain , A Sadaka , S Berry CASE SERIES 1,2,3,4,5,6 associated with carotid and AG Lee vascular occlusion Abstract the literature as benign episodic pupillary dilation or BEUM. We report two patients with Purpose To describe two cases of 1 stereotyped, intermittent, neurologically acquired occlusive disease of the ipsilateral ICA Department of Ophthalmology, Blanton isolated, unilateral mydriasis in patients who developed multiple, stereotyped, neurologically isolated, transient episodes of Eye Institute, Houston with a history of acquired internal carotid Methodist Hospital, artery (ICA) occlusive disease on the mydriasis consistent with BEUM. We discuss the Houston, TX, USA ipsilateral side. possible mechanisms, differential diagnosis and 2 Patients Two patients with intermittent recommended evaluation for atypical cases for Department of episodic mydriasis. Ophthalmology, Baylor mydriasis. College of Medicine, Methods Case Series. Houston, TX, USA Results Case one: A 78-year-old man Case one 3 experienced 10 episodes of intermittent, Departments of Ophthalmology, Neurology, unilateral, and painless mydriasis in the left A 78-year-old man presented with 10 episodes of and Neurosurgery, Weill stereotyped, intermittent, unilateral, painless eye and had 100% occlusion of the left ICA Cornell Medical College, artery due to atherosclerotic disease. Case two: pupillary dilation of the left eye (OS) lasting New York, NY, USA A 26-year-old woman with history of migraine minutes to hours at a time without diplopia or fi 4Department of developed new painless, intermittent episodes ptosis. -

Diplopia Following Cataract Surgery: a Review of 150 Patients

Eye (2008) 22, 1057–1064 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/eye Diplopia following H Nayak, JP Kersey, DT Oystreck, RA Cline and CLINICAL STUDY CJ Lyons cataract surgery: a review of 150 patients Abstract Eye (2008) 22, 1057–1064; doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702847; published online 27 April 2007 Aim To study the motility pattern, underlying mechanism, and management of Keywords: cataract; diplopia; strabismus; patients who complained of double vision anaesthesia after cataract surgery. Methods A retrospective case note analysis of 150 patients presenting with diplopia after cataract surgery to an orthoptic clinic over a Introduction 70-month period. Information was retrieved from orthoptic, ophthalmological, and The recent rapid evolution of cataract surgical operating room records. technique has made this one of the most Results A total of 3% of patients presenting commonly performed and successful surgical to the orthoptic clinic had diplopia after procedures. However, the substantial benefit of cataract surgery. We grouped these according visual acuity improvement resulting from to the underlying mechanisms which were: cataract extraction can be reduced by the (1) decompensating pre-existing strabismus introduction of post-operative diplopia. Most of (34%), (2) extraocular muscle restriction/ the recent literature regarding the cause of this paresis (25%), (3) refractive (8.5%), complication1–20 has focused on anaesthetic (4) concurrent onset of systemic disease myotoxicity, trauma during infiltrational (5%), (5) central fusion disruption (5%), and anaesthesia, or the use of a rectus bridle suture. (6) monocular diplopia (2.5%). Twenty per cent In this study, we reviewed the motility of the patients could not be categorised with characteristics, likely aetiology, and Department of certainty. -

Diplopia As the Presenting Symptom of Type 1 Diabetes

Diabetes Care Volume 37, March 2014 e45 Diplopia as the Presenting Charlotte G. Krol, Frederikus A. Klok, and Eelco J.P. de Koning Symptom of Type 1 Diabetes Diabetes Care 2014;37:e45–e46 | DOI: 10.2337/dc13-2244 Neuropathy is a common complication was the diagnosis. Given his normal nerve, sparing the superomedial- of diabetes, in which cranial nerve BMI and rapidly progressive symptoms, concentrated pupillomotor fibers and palsies are rare and associated with type 1 diabetes was considered the thereby pupil function, in contrast to long-standing poorly controlled type 2 most likely diagnosis. Therefore, and palsies due to other diagnoses (4,5). diabetes. We report a case of a young because cranial mononeuropathy Differential diagnoses include patient with oculomotor nerve palsy as requires rapid correction of infectious diseases, aneurysms, the presenting symptom of type 1 hyperglycemia, insulin therapy was inflammatory disorders, tumors, diabetes. initiated immediately. Normoglycemia trauma, and surgery (4). Diabetic A 36-year-old previously healthy was achieved with a basal-bolus reg- oculomotor nerve palsies typically Sudanese man was referred to our imen and a daily dose of 0.67 units/kg recover over weeks to months emergency department because of within a few weeks. Four months after without sequelae. Management is ’ progressive diplopia of his right eye for the initial diagnosis, the patient socu- supportive, including optimal glycemic 7 days. At the emergency department, lomotor nerve palsy had improved controlaswellasminimizationofother he also reported weight loss, fatigue, dramatically, with almost complete risk factors for ischemia, including control of blood pressure and lipid excessive thirst, and polyuria in the resolution of symptoms. -

Miotic Adie's Pupils

Journal of Cll/lical Neuro-ophtllJllmology 9(1): 43-45, 1989. RilVen Press, Ltd., New York Miotic Adie's Pupils Michael L. Rosenberg, M.D. Two young adults, aged 24 and 31, had a long history of Adie's syndrome or, pupillotonia, is typically small, poorly reactive pupilS. There was no history of characterized by either unilaterally or bilaterally large pupils, and a review of old photographs confirmed enlarged pupils that are unresponsive to light (1). 10 and 5 years, respectively, of miosis. Both were found to have bilateral tonic pupils that were supersensitive to The diagnosis is made clinically by watching for a diluted pilocarpine. Although it is possible that they had tonic constriction to near stimulation followed by a an unusually early onset of bilateral Adie's syndrome tonic redilatation. with dilated pupils that was not noticed, it is suggested Two young adults are described who were noted that some patients might have primary miotic Adie's during routine examinations to have bilaterally mi pupils without ever passing through a mydriatic phase. Key Words: Adie's syndrome-Argyll Robertson pu otic pupils that were thought to be fixed to light. pils-Miosis. They were both referred for the evaluation of Ar gyll Robertson pupils. Evaluation revealed bilat eral tonic reactions to near stimulation in both pa tients, typical of Adie's tonic pupilS. The diagnosis of parasympathetic denervation was confirmed in both patients as their pupils constricted with di luted pilocarpine. The cases reinforce the principle that any pupil regardless of size should be evalu ated for the possibility of pupillotonia. -

Visual Symptoms and Findings in MS: Clues and Management

6/5/2014 Common visual symptoms and findings in MS: Clues and Identification Teresa C Frohman, PA-C, MSCS Neuro-ophthalmology Research Manager, UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Professor Biomedical Engineering, University of Texas Dallas COMMON COMPLAINTS 1 6/5/2014 Blurry Vision Corrected with Refraction? YES NO Refractive Keep Looking Error IN MS : ON, Diplopia, Nystagmus Most Common Visual Issues Encountered in MS patients • Optic Neuritis • Diplopia • Nystagmus result from damage to the optic nerve or from an incoordination in the eye muscles or damage to a part of the oculomotor pathway or apparatus 2 6/5/2014 Optic Neuritis Workup ‘frosted glass’ Part of visual field missing Pain +/- Color desaturation Work up for Yes diplopia or nystagmus Seeing double images YES NO Or ‘jiggling’ No Neuro-ophth exam Humphrey’s OCT MRI Fundoscopy CRANIAL NERVE ANATOMY There are 12 pairs of cranial nerves CN I Smell CN II Vision CN III, IV, VI Oculomotor CN V Trigeminal Sensorimotor muscles of the Jaw CN VII Sensorimotor of the face CN VIII Hearing//vestibular CN IX, X, XII Mouth, esophagus, oropharynx CN XI Cervical Spine and shoulder 6 3 6/5/2014 NEURO-OPHTHALMOLOGY EXAM Visual Acuity Color Vision Afferent pupillary reaction- objective test of CNII function Alternating flashlight test – afferent arc of pupillary light reflex pathway Fundus exam Visual Fields –confrontation at bedside CRANIAL NERVE II: OPTIC once the retinal ganglion cell axons leave the back of the eye they become myelinated behind the lamina cribosa ---and