Table of Contents: Acknowledgments Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Points Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D

Please join us for a Post-Show Discussion immediately following this performance. Photo by Allen Weeks by Photo FIVE POINTS BOOK BY HARRISON DAVID RIVERS MUSIC BY ETHAN D. PAKCHAR & DOUGLAS LYONS LYRICS BY DOUGLAS LYONS DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY DENISE PROSEK CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER WORLD PREMIERE • APRIL 4 - MAY 6, 2018 • RITZ THEATER Theater Latté Da presents the world premiere of FIVE POINTS Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D. Pakchar & Douglas Lyons Lyrics by Douglas Lyons Directed by Peter Rothstein** Music Direction by Denise Prosek† Choreography by Kelli Foster Warder FEATURING Ben Bakken, Dieter Bierbrauer*, Shinah Brashears*, Ivory Doublette*, Daniel Greco, John Jamison, Lamar Jefferson*, Ann Michels*, Thomasina Petrus*, T. Mychael Rambo*, Matt Riehle, Kendall Anne Thompson*, Evan Tyler Wilson, and Alejandro Vega. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors ** Member of SDC, the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a national theatrical labor union †Member of Twin Cities Musicians Union, American Federation of Musicians FIVE POINTS will be performed with one 15-minute intermission. Opening Night: Saturday, April 7, 2018 ASL Interpreted and Audio Described Performance: Thursday, April 26, 2018 Meet The Writers: Sunday, April 8, 2018 Post-Show Discussions: Thursdays April 12, 19, 26, and May 3 Sundays April 11, 15, 22, 29, and May 6 This production is made possible by special arrangement with Marianne Mills and Matthew Masten. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. As a courtesy to the performers and other patrons, please check to see that all cell phones, pagers, watches, and other noise-making devices are turned off. -

Year 8 Dance Project Black History Through Dance

Year 8 Dance Project Black History Through Dance I am trying to show the world that we are all human beings and that colour is not important. What is important is the quality of our work – Alvin Ailey A range of dance styles originated through black history including the tribal dances of Africa, the slave dances of the West Indies and the American Deep South, the Harlem social dances of the 1920s and the jazz dance of Broadway musicals. These styles of dance are hugely influential, inspiring new choreography as well as supporting the story of black history. TASK 1 – Read all of the information below Africa and the West Indies The two main origins of black dance are African dance and the slave dances from the plantations of the West Indies. Tribes or ethnic groups from every African country have their own individual dances. Dance has a ceremonial and social function, celebrating and marking rites of passage, sex, the seasons, recreation and weddings. The dancer can be a teacher, commentator, spiritual medium, healer or storyteller. In the Caribbean each island has its own traditions that come from its African roots and the island’s particular colonial past – British, French, Spanish or Dutch. 18th-century black dances such as the Calenda and Chica were slave dances which drew on African traditions and rhythms. The Calenda was one of the most popular slave dances in the Caribbean. It was banned by many plantation owners who feared it would encourage social unrest and uprisings. In the Calenda men and women face each other in two lines moving towards each other than away, then towards each other again to make contact - slapping thighs and even kissing. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board

Encyclopedia of African American Music Advisory Board James Abbington, DMA Associate Professor of Church Music and Worship Candler School of Theology, Emory University William C. Banfield, DMA Professor of Africana Studies, Music, and Society Berklee College of Music Johann Buis, DA Associate Professor of Music History Wheaton College Eileen M. Hayes, PhD Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology College of Music, University of North Texas Cheryl L. Keyes, PhD Professor of Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles Portia K. Maultsby, PhD Professor of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Director of the Archives of African American Music and Culture Indiana University, Bloomington Ingrid Monson, PhD Quincy Jones Professor of African American Music Harvard University Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., PhD Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Music University of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia of African American Music Volume 1: A–G Emmett G. Price III, Executive Editor Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Associate Editors Copyright 2011 by Emmett G. Price III, Tammy L. Kernodle, and Horace J. Maxile, Jr. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of African American music / Emmett G. Price III, executive editor ; Tammy L. Kernodle and Horace J. Maxile, Jr., associate editors. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-313-34199-1 (set hard copy : alk. -

Representations of Blackface and Minstrelsy in Twenty- First Century Popular Culture

Representations of Blackface and Minstrelsy in Twenty- First Century Popular Culture Jack HARBORD School of Arts and Media University of Salford, Salford, UK Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, June 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures iii Acknowledgements vii Abstract viii Introduction 1 1. Literature Review of Minstrelsy Studies 7 2. Terminology and Key Concepts 20 3. Source Materials 27 4. Methodology 39 5. Showing Blackface 5.1. Introduction 58 5. 2. Change the Joke: Blackface in Satire, Parody, and Irony 59 5. 3. Killing Blackface: Violence, Death, and Injury 95 5. 4. Showing Process: Burnt Cork Ritual, Application, and Removal 106 5. 5. Framing Blackface: Mise-en-Abyme and Critical Distance 134 5. 6. When Private goes Public: Blackface in Social Contexts 144 6. Talking Blackface 6. 1. Introduction 158 6. 2. The Discourse of Blackface Equivalency 161 6. 3. A Case Study in Blackface Equivalency: Iggy Azalea 187 6. 4. Blackface Equivalency in Non-African American Cultural Contexts 194 6. 5. Minstrel Show Rap: Three Case Studies 207 i Conclusions: Findings in Contemporary Context 230 References 242 ii List of Figures Figure 1 – Downey Jr. playing Lazarus playing Osiris 30 Figure 2 – Blackface characters in Mantan: The New Millennium Minstrel Show 64 Figure 3 – Mantan: Cotton plantation/watermelon patch 64 Figure 4 – Mantan: chicken coup 64 Figure 5 – Pierre Delacroix surrounded by African American caricature memorabilia 65 Figure 6 – Silverman and Eugene on return to café in ‘Face -

Of the Blues Aesthetic

Skansgaard 1 The “Aesthetic” of the Blues Aesthetic Michael Ryan Skansgaard Homerton College September 2018 This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Skansgaard 2 Declaration: This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,829 words, the thesis does not exceed the regulation length, including footnotes, references and appendices but excluding the bibliography. This work follows the guidelines of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. Acknowledgements: This study has benefitted from the advice of Fiona Green and Philip Coleman, whose feedback has led to a revitalised introduction and conclusion. I am also indebted to Donna Akiba Sullivan Harper, Robert Dostal, Kristen Treen, Matthew Holman, and Pulane Mpotokwane, who have provided feedback on various chapters; to Simon Jarvis, Geoff Ward, and Ewan Jones, who have served as advisers; and especially to my supervisor, Michael D. -

Staging American Voice by Caitlin Simms Marshall a Dissertation

‘Power in the Tongue’ Staging American Voice By Caitlin Simms Marshall A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in New Media In the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Abigail DeKosnik, Chair Professor Shannon Steen Professor Susan Schweik Professor Nina Eidsheim Summer 2016 Abstract ‘Power in the Tongue’: Staging American Voice By Caitlin Simms Marshall Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California Berkeley Professor Abigail DeKosnik, Chair Voice is the chief metaphor for power and enfranchisement in American democracy. Citizens exercising rights are figured as ‘making their voices heard,’ social movements are imagined as ‘giving voice to the voiceless,’ and elected leaders represent ‘the voice of the people.’ This recurring trope forces the question: does citizenship have a sound, and if so, what voices count? Scholars of American studies and theater history have long been interested in nineteenth-century national formation, and have turned to speech, oratory, and performance to understand the role of class, gender, and race in shaping the early republic (Fliegelman 1993, Looby 1996, Gustafson 2000, Lott 1993, Deloria 1998, Nathans 2009, Jones 2014). However, these studies are dominated by textual and visual modes of critique. The recent academic turn to sound studies has produced scholarship on the sonic formation of minoritarian American identity and an American cultural landscape. Yet this body of research all but overlooks voice performance as site of inquiry. As a result, research has disregarded a central sensory pathway through which democracy operates. -

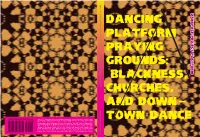

Dancing Platform Praying Grounds

DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWNTOWN DANCE DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, DANCING DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWN- Danspace Project Platform TOWN DANCE ISBN 978-0-9700313-8-9 Since 2010, Danspace Project has published catalogues as part of its series of artist-curat- ed Platforms. Initiated by Danspace Project Executive Director and Chief Curator Judy 90000> Hussie-Taylor, the Platforms, "exhibitions that unfold over time," contextualize contem- porary dance and performance practices and histories. The 12th edition, Dancing Plat- form Praying Grounds: Blackness, Churches, and Downtown Dance, is edited by Reggie Wilson, Lydia Bell, and Kristin Juarez. Contributors include: Lauren Bakst, Lydia Bell, Thomas F. DeFrantz, Stephen Facey, Keely Garfield, Judy Hussie-Taylor, Darrell Jones, Prithi Kanakamedala, Kelly Kivland, Cynthia Oliver, Susan Osberg, Carl Paris, Julian Rose, Same As Sister (Hilary Brown and Briana Brown-Tipley), Radhika Subramaniam, 9 780970 031389 Kamau Ware, Ni’Ja Whitson, Tara Aisha Willis, Mabel O. Wilson, and Reggie Wilson. DANSPACE PROJECT PLATFORM DANCING PLATFORM PRAYING GROUNDS: BLACKNESS, CHURCHES, AND DOWN- TOWN DANCE Published by Danspace Project, New York, BOARD OF DIRECTORS on the occasion of Dancing Platform Praying Grounds: Blackness, Churches, and Down- President town Dance, curated by Reggie Wilson as Helen Warwick part of the Platform series at Danspace Project First Vice President Sam Miller First edition ©2018 Danspace Project Treasurer All rights reserved under pan-American copy- Sarah Needham right conventions. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or Secretary by any means without permission in writing David Parker from the publisher. -

Knockabout and Slapstick: Violence and Laughter in Nineteenth-Century Popular Theatre and Early Film

Knockabout and Slapstick: Violence and Laughter in Nineteenth-Century Popular Theatre and Early Film by Paul Michael Walter Babiak A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto ©Copyright by Paul Michael Walter Babiak, 2015 Knockabout and Slapstick: Violence and Laughter in Nineteenth-Century Popular Theatre and Early Film Paul Michael Walter Babiak Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Studies University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This thesis examines laughter that attends violent physical comedy: the knockabout acts of the nineteenth-century variety theatres, and their putative descendants, the slapstick films of the early twentieth-century cinema. It attempts a comparative functional analysis of knockabout acts and their counterparts in slapstick film. In Chapter 1 of this thesis I outline the obstacles to this inquiry and the means I took to overcome them; in Chapter 2, I distinguish the periods when knockabout and slapstick each formed the dominant paradigm for physical comedy, and give an overview of the critical changes in the social context that separate them. In Chapter 3, I trace the gradual development of comedy films throughout the early cinema period, from the “comics” of 1900 to 1907, through the “rough house” films of the transitional era, to the emergence of the new genre in 1911-1914. ii Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 present my comparative analyses of the workings of four representative -

The Magazine of Clogging Since 1983

The Magazine of Clogging Since 1983 TIMES DOUBLETOEwww.doubletoe.com December 2015 January 2016 Issue DOUBLETOE footprint December 2015 Our “Good Old Days” January 2016 Sometimes it is hard for me to imagine, but I have been involved in clogging and old time dance for 40 years. I started as a square dancer, and began clogging my first In This Issue year off college. I’ve seen so many changes in my time that the dance that I first encountered in the late 1970’s is Index ....................................................................2 hardly recognizable today. Footprint “Our Good Old Days” ...........................2 For those of us who were a part of the activity back then, Calendar of Events ..............................................4 today’s social media has become a means of sharing memories of those times and capturing the golden CLOG, Inc. National Clogging Convention ..........6 moments that are the time stamp of our “good old days.” Cloggers in the Spotlight: The term is certainly a cliché in popular culture. It usually is Students step up for Lancashire Lessons ......14 used when referring to an era considered by the presenter as being better than the current era. It is a form of nostalgia The Willis Clan...................................................16 and romanticism of a certain time. Percussive Dance History: For me and so many others who have been clogging for Buck, Flatfoot and Wings................................18 decades, we fondly look back on our “good old days” with an almost spiritual reverence. We cannot understand how Travelling Shoes: many of the young people of today could turn their noses Clogging at the Owl Cafe...................................24 up at the idea of clogging workshops and roll their eyes at Kriss Sands Flatfooting......................................26 the thought of an evening of fun dancing, mixers, square dancing and freestyling. -

Juba's Dance: an Assessment of Newly Acquired Documentation

Juba’s Dance: An Assessment of Newly Acquired Documentation Stephen Johnson, University of Toronto In 1947 the dance and popular culture historian Marian Hannah Winter wrote an article called ‘Juba and American Minstrelsy,’ in which she traced– and made significant– the life of the black American dancer William Henry Lane, who performed in the United States and in Britain as ‘Juba’ during the 1840s.1 That biography portrayed a clear path of rising prominence and influence. Born in the United States, circa 1825, Juba was– according to Winter– performing in dance houses in New York City by the early 1840s, where he was described by Charles Dickens. Juba danced in competitions, variety houses, and with a new phenomenon, the minstrel show, until 1848, when he travelled to England. He appeared at Vauxhall Gardens with the minstrel troupe ‘Pell's Ethiopian Serenaders,’ where his unusual dance technique drew extravagant praise. Juba remained in England, on tour, until his early death in 1852. Prior to Winter's article, Juba was a forgotten figure, the only references to him a few lines in histories of minstrelsy.2 Winter carved out for Juba a place of importance in subsequent histories of American performance– that he provided integrity to a developing indigenous dance idiom, based on his direct links with an African-American folk culture. His active participation in the development of that idiom– to Winter, he was the progenitor of what became jazz and tap dance– re-appropriated for black cultural history what otherwise was a clear case, in American blackface minstrelsy, of theft. -

Zack Whitman Gill

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Using the Master’s Tools: Representations of Blackness and the Strategies of Stereotype A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre By Aimee Zygmonski Committee in charge: Professor Frank B. Wilderson, III, Chair Professor Patrick Anderson Professor Jim Carmody Professor Camille F. Forbes Professor Emily Roxworthy 2010 Copyright 2010 Aimee Zygmonski All rights reserved The Dissertation of Aimee Zygmonski is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2010 iii DEDICATION To Stella and Scupper, because of you, not in spite of you, this dissertation sees its end And To Steve because without you, this dissertation would have languished in the Great Hole of History, for with you, I am whole iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Dedication .......................................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents .................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi Vita ...................................................................................................................................