"Peg Leg" Bates: Monoped Master

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Courtney Harding, Is Excited to Start Her Second Year As a TACT Academy Instructor

Denise S Bass, has several television credits to her name including Matlock, One Tree Hill, HBO's East Bound and Down with Danny McBride and Katy Mixon, and TNT's production of T-Bone and Weasel starring Gregory Hines, Christopher Lloyd, and Wayne Knight. Also to her credit are several film productions including The Road to Wellville with Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Broderick, Black Knight with Martin Laurence, and The 27 Club with Joe Anderson. She has been performing theatrically since 1981 working from NC to Florida and touring the Southeast with the American Family Theatre out of Philadelphia. Denise's most recent roles include Ethel in Thalian Association's production of "Barefoot in the Park" (Winner 2017 Thalian Award Best Actress in a Play), Dottie in Thalian Association's production of "Noises Off" (Nominee 2016 Thalian Award Best Supporting Actress in a Play), and Madam Thenadier in Opera House Theatre Company's production of Les Miserable. Other notable roles over the years include Sally in "Follies", Dolly Levi in "Hello, Dolly!", Molly Brown in "The Unsinkable Molly Brown", Delightful in "Dearly Departed", Diana Morales in "A Chorus Line", and Mrs. Meers in "Throughly Modern Mille”. She is a producer and featured performer with Ensemble Audio Studios and was part of the cast for the audio production of "The King's Child", which was selected in 2017 at the Hear Now Audio Festival for the Gold Circle Page. She also voiced several characters for the very popular audio book "Percy the Cat and the Big White House". She is currently writing a collection of short stories and looks forward to teaching Fundamentals of Acting for TACT. -

Bill 'Bojangles'

‘It’s all the way you look at it, you know’: reading Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson’s film career Author: Hannah Durkin Affiliation: University of Nottingham, UK This article engages with a major paradox in African American tap dancer Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson’s film image – namely, its concurrent adherences to and contestations of dehumanising racial iconography – to reveal the complex and often ambivalent ways in which identity is staged and enacted. Although Robinson is often understood as an embodiment of popular cultural imagery historically designed to dehumanise African Americans, this paper shows that Robinson’s artistry displaces these readings by providing viewing pleasure for black, as much as white, audiences. Robinson’s racially segregated scenes in Dixiana (1930) and Hooray for Love (1935) illuminate classical Hollywood’s racial codes, whilst also showing how his inclusion within these otherwise all-white films provides grounding for creative and self-reflexive artistry. The films’ references to Robinson’s stage image and artistry overlap with minstrelsy-derived constructions of ‘blackness’, with the effect that they heighten possible interpretations of his cinematic persona by evading representational conclusion. Ultimately, Robinson’s films should be read as sites of representational struggle that help to uncover the slipperiness of performances of African American identities in 1930s Hollywood. Keywords: Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson; tap dance; minstrelsy; specialty number; classical Hollywood Hannah Durkin. Email: [email protected] In 1935 musical Hooray for Love, a character played by Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson (1878-1949), one of Hollywood’s first black screen stars, declares, ‘it’s all the way you look at it, you know’ to describe his surroundings. -

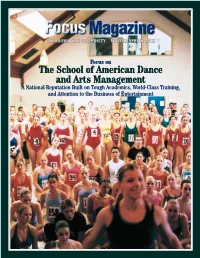

Focus Winter 2002/Web Edition

OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Focus on The School of American Dance and Arts Management A National Reputation Built on Tough Academics, World-Class Training, and Attention to the Business of Entertainment Light the Campus In December 2001, Oklahoma’s United Methodist university began an annual tradition with the first Light the Campus celebration. Editor Robert K. Erwin Designer David Johnson Writers Christine Berney Robert K. Erwin Diane Murphree Sally Ray Focus Magazine Tony Sellars Photography OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY • WINTER/SPRING 2002 Christine Berney Ashley Griffith Joseph Mills Dan Morgan Ann Sherman Vice President for Features Institutional Advancement 10 Cover Story: Focus on the School John C. Barner of American Dance and Arts Management Director of University Relations Robert K. Erwin A reputation for producing professional, employable graduates comes from over twenty years of commitment to academic and Director of Alumni and Parent Relations program excellence. Diane Murphree Director of Athletics Development 27 Gear Up and Sports Information Tony Sellars Oklahoma City University is the only private institution in Oklahoma to partner with public schools in this President of Alumni Board Drew Williamson ’90 national program. President of Law School Alumni Board Allen Harris ’70 Departments Parents’ Council President 2 From the President Ken Harmon Academic and program excellence means Focus Magazine more opportunities for our graduates. 2501 N. Blackwelder Oklahoma City, OK 73106-1493 4 University Update Editor e-mail: [email protected] The buzz on events and people campus-wide. Through the Years Alumni and Parent Relations 24 Sports Update e-mail: [email protected] Your Stars in action. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Winter 2018 at Seattle Theatre Group

WINTER 2018/2019 SEATTLE THEATRE GROUP 2 • 0 • 1 • 8 - 2• 0 • 1 • 9 Saleea, Age 12 Give the gift. Of pioneering research. Of caring for all kids in all communities. Of helping families afford lifesaving care. Give the gift of hope. The gift of care. The gift of cures. When you make a donation to Seattle Children’s, you provide hope to kids like Saleea. See what your yes can do at seattlechildrens.org/yestosaleea CHILD 13701-3 Yes Saleea_Encore_R1.indd 1 10/30/18 4:27 PM Pub/s: Encore (Saleea) Traffic: 10/29/18 Run Date: December Color: CMYK Author: TH Trim: 8.375”w x 10.875”h Live: 7.375”w x 9.875”h Bleed: 8.625”w x 11.125”h Round#: 1 November 2018 Volume 15, No. 2 WELCOMEFrom Seattle Theatre Group, a non-profit arts organization Paul Heppner President Mike Hathaway Welcome! As we move through the holidays and into the new year we are Senior Vice President excited to continue our 2018/2019 Performing Arts Season with an eclectic Kajsa Puckett lineup of performances of the highest caliber. With works from innovative Vice President, Sales & Marketing musicians and dancers, as well as festive family entertainment, we invite you Genay Genereux to join us in sending 2018 out on the highest of notes and giving a rousing Accounting & Office Manager welcome to 2019! Production First up is The Hip Hop Nutcracker, a contemporary re-imagination of Susan Peterson Tchaikovsky’s timeless music, featuring special guest MC and hip-hop legend Vice President, Production Kurtis Blow. -

Sammy Davis Jr.'S Facts on Tap Dancing | Entertainment Guide

FIND LOCAL: Entertainment Guide Parties & Celebrations | Travel & Attractions | Sports & Recreation | Leisure Activities Entertainment Guide » Arts & Entertainment » Dance » Dancing » Sammy Davis Jr.'s Facts on Tap Dancing Sammy Davis Jr.'s Facts on Tap Dancing ADS BY GOOGLE by Sue McCarty, Demand Media In May 1990, the Las Vegas Strip went dark for 10 minutes to honor one of America's premier entertainers, Sammy Davis Jr. Davis began his professional life on a vaudeville stage tap dancing at the age of 3 and spent the next 61 years singing, dancing, impersonating and acting for an often racially prejudiced public. Tutored in tap by his father, Sammy Sr., and partner, Will Mastin, and advised by the immortal Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Davis spent his entire life on stages, in films and on television. Fred Astaire once said of Davis, "Just to watch him walk on stage was worth the price of admission." Learning the Craft Davis referred to his tap dancing skills as “a hand-me-down art form" because he was never formally trained in any aspect of dance. He learned by watching and imitating his father, Mastin and other professionals he came in contact with every night on vaudeville stages across the country. According to Davis, he remembered everything he saw, including timing, audience reaction to certain moves and how to direct the mood of the audience with facial expressions and gestures. RELATED ARTICLES Developing a Style Interesting Facts About Irish Step At the age of 10 Davis first saw Bill "Bojangles" Robinson on stage in Dancing Boston, which changed Davis' whole approach to tap dancing. -

Five Points Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D

Please join us for a Post-Show Discussion immediately following this performance. Photo by Allen Weeks by Photo FIVE POINTS BOOK BY HARRISON DAVID RIVERS MUSIC BY ETHAN D. PAKCHAR & DOUGLAS LYONS LYRICS BY DOUGLAS LYONS DIRECTED BY PETER ROTHSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTION BY DENISE PROSEK CHOREOGRAPHY BY KELLI FOSTER WARDER WORLD PREMIERE • APRIL 4 - MAY 6, 2018 • RITZ THEATER Theater Latté Da presents the world premiere of FIVE POINTS Book by Harrison David Rivers Music by Ethan D. Pakchar & Douglas Lyons Lyrics by Douglas Lyons Directed by Peter Rothstein** Music Direction by Denise Prosek† Choreography by Kelli Foster Warder FEATURING Ben Bakken, Dieter Bierbrauer*, Shinah Brashears*, Ivory Doublette*, Daniel Greco, John Jamison, Lamar Jefferson*, Ann Michels*, Thomasina Petrus*, T. Mychael Rambo*, Matt Riehle, Kendall Anne Thompson*, Evan Tyler Wilson, and Alejandro Vega. *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors ** Member of SDC, the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, a national theatrical labor union †Member of Twin Cities Musicians Union, American Federation of Musicians FIVE POINTS will be performed with one 15-minute intermission. Opening Night: Saturday, April 7, 2018 ASL Interpreted and Audio Described Performance: Thursday, April 26, 2018 Meet The Writers: Sunday, April 8, 2018 Post-Show Discussions: Thursdays April 12, 19, 26, and May 3 Sundays April 11, 15, 22, 29, and May 6 This production is made possible by special arrangement with Marianne Mills and Matthew Masten. The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. As a courtesy to the performers and other patrons, please check to see that all cell phones, pagers, watches, and other noise-making devices are turned off. -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error. -

Year 8 Dance Project Black History Through Dance

Year 8 Dance Project Black History Through Dance I am trying to show the world that we are all human beings and that colour is not important. What is important is the quality of our work – Alvin Ailey A range of dance styles originated through black history including the tribal dances of Africa, the slave dances of the West Indies and the American Deep South, the Harlem social dances of the 1920s and the jazz dance of Broadway musicals. These styles of dance are hugely influential, inspiring new choreography as well as supporting the story of black history. TASK 1 – Read all of the information below Africa and the West Indies The two main origins of black dance are African dance and the slave dances from the plantations of the West Indies. Tribes or ethnic groups from every African country have their own individual dances. Dance has a ceremonial and social function, celebrating and marking rites of passage, sex, the seasons, recreation and weddings. The dancer can be a teacher, commentator, spiritual medium, healer or storyteller. In the Caribbean each island has its own traditions that come from its African roots and the island’s particular colonial past – British, French, Spanish or Dutch. 18th-century black dances such as the Calenda and Chica were slave dances which drew on African traditions and rhythms. The Calenda was one of the most popular slave dances in the Caribbean. It was banned by many plantation owners who feared it would encourage social unrest and uprisings. In the Calenda men and women face each other in two lines moving towards each other than away, then towards each other again to make contact - slapping thighs and even kissing. -

ROBINSON, WILLIAM E.: Papers, 1935-69

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS ROBINSON, WILLIAM E.: Papers, 1935-69 William E. Robinson held positions as a newspaper executive with the New York Evening Journal (1933-36) and the New York Herald Tribune (1936-54), directed his own public relations firm of Robinson-Hannegan Associates (1954-55), and served as president and chairman of the board of Coca-Cola, Inc. (1955-61). In addition to having a long and distinguished career in business, Mr. Robinson also enjoyed a long and close personal friendship with Dwight D. Eisenhower, dating from their first meeting in World War II until their deaths in 1969. Mr. Robinson’s papers reflect both his business career and, especially, his association with Dwight D. Eisenhower. Mr. Robinson first met General Eisenhower in 1944 when the former was in Europe to reestablish publication of the Herald Tribune’s European edition. Their association became more intimate in 1947 when Mr. Robinson prevailed upon the General to write his World War II memoirs. According to arrangements worked out by Mr. Robinson, General Eisenhower’s Crusade in Europe came out in the fall of 1948, published in book form by Doubleday and syndicated to newspapers worldwide by the Herald Tribune. The two men were drawn together by a great admiration and respect for each other’s ideas and judgments, and an abiding common passion for playing bridge and golf. It was Mr. Robinson, in the spring of 1948 after the General had finished drafting his memoirs, who first introduced the Eisenhowers to Augusta National Golf Club. When General Eisenhower became president of Columbia University in New York City, the two had frequent occasions to play bridge together and to enjoy a game of golf at Blind Brook Golf Club where Mr. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}.