Reflections on a Sustainable Model for a Community Orchestra in Aotearoa New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Fatele Theology: a Contextual Theological Response in Addressing Threats of Global Warming in Tuvalu

Towards Fatele Theology: A Contextual Theological Response in Addressing Threats of Global Warming in Tuvalu A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Theology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For The Degree of Master of Theology By Maina Talia Advisor: Prof, Dr. M.P. Joseph Tainan Theological College and Seminary Tainan, Taiwan May 2009 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2009 Maina Talia ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to the followings: My parents Talia Maina Salasopa and the late Lise Moeafu Talia, OBE. Mum, your fatele’s will remains as living text for the Tuvaluan generations in their search for the presence of the Divine. And my grandma Silaati Telito, in celebrating her 90th Birthday. ! ! i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT “So you also, when you have done everything you were told to do, should say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done our duty.” (Luke 17:10) The completion of this thesis is not an individual achievement. Without the help of many, it would never have come to a final form. Because I was not endorsed by the Ekalesia Kelisiano Tuvalu, it remains dear to me. Rev. Samuelu Tialavea Sr the General Secretary of the Congregational Christian Church in American Samoa (CCCAS) offered his church’s sponsorship. I owe a big fa’afetai tele to the CCCAS and the Council for World Mission for granting me a scholarship. Fakafetai lasi kii to my thesis advisor Prof, Dr. M.P. Joseph great theologian, who helped me through the process of writing, especially giving his time for discussion. His constructive advice and words of encouragement contributed in many ways to the formation of fatele theology. -

Dancing Fulbrighters 60 Years of Dance Exchanges on the New Zealand Fulbright Programme

Dancing Fulbrighters 60 years of dance exchanges on the New Zealand Fulbright programme Jennifer Shennan © Jennifer Shennan 2008 Published by Fulbright New Zealand, November 2008 The opinions and views expressed in this booklet are the personal views of the author and contributors and do not represent in whole or part the opinions of Fulbright New Zealand. See inside back cover for photograph captions and credits. ISBN 978-1-877502-04-0 (print) ISBN 978-1-877502-05-7 (PDF) Sixty years of Dancing Fulbrighters A handsome volume, Fulbright in New Zealand, Educational Foundation (Fulbright New Zealand) published in 1988, marked the 40th anniversary of and New Zealand Council for Educational Research the Fulbright exchange programme’s operation in this were Coming and Going: 40 years of the Fulbright country. The author, Joan Druett, herself a Fulbrighter, Programme in New Zealand as well as conference affi rmed what other participants already knew, namely proceedings – The Impact of American Ideas on New that a Fulbright award for a visit to or from the United Zealand Education, Policy and Practice. Dance has States, whether for a year’s teaching exchange, clearly been one of the subject areas to benefi t from an extended research project, or a short-term the introduction of American ideas in New Zealand intensive visit, could prove an infl uential milestone in education, both in policy and practice, even if it took professional career and personal life. some time to come to fruition. For many, those infl uences have continued To help mark the 60th anniversary of the Fulbright for decades, not recalled merely for sentiment or Programme here, I proposed profi ling some of the nostalgia, but for the wider context developed for many fellows across 60 years whose projects had one’s fi eld of study, and as an energizing reminder been in dance, whether as choreographers, teachers, of the potential for goodwill in “inter-national” performers, writers or educationalists, either New projects. -

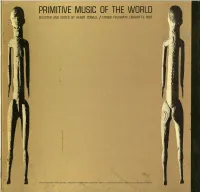

PRIMITIVE MUSIC of the WORLD Selected and Edited by Henry Cowell

ETHNIC FOLKWAYS LIBRARY Album # FE 4581 ©1962 by Folkways Records & Service Corp., 121 W. 47th St. NYC USA PRIMITIVE MUSIC OF THE WORLD Selected and Edited by Henry Cowell by Henry Cowell Usually, however, there are two, three, four or five different tones used in primitive melodies. Some peoples in different parts of the world live These tones seem to be built up in relation to under more primitive conditions than others, one another in two different ways; the most and in many cases their arts are beginning common is that the tones should be very close points. In the field of the art of sound there is together - a 1/2 step or closer, never more than a whole step. This means that the singer great variety to be found; no two people I s music is alike, and in some cases there is much com tenses or relaxes the vocal cords as little as plexity. In no case is it easy for an outsider to possible; instruments imitate the voice. The imitate, even when it seems very simple. other method of relationship seems to be de rived from instruments, and is the result of While all music may have had outside influence over-blowing on pipes, flutes, etc. From this at one time, we think of music as being primi is de.rived wide leaps, the octave, the fifth tive if no outside influence can be traced, or in and the fourth. These two ways are sometimes some cases where there is some influence from combined (as in cut #2 of flutes from New other primitive sources. -

Wellington Jazz Among the Discourses

1 OUTSIDE IN: WELLINGTON JAZZ AMONG THE DISCOURSES BY NICHOLAS PETER TIPPING A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 2 Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: Conundrums, questions, contexts ..................................................................... 9 Sounds like home: New Zealand Music ............................................................................... 15 ‘Jazz’ and ‘jazz’...................................................................................................................... 17 Performer as Researcher ...................................................................................................... 20 Discourses ............................................................................................................................ 29 Conundrums ........................................................................................................................ -

DOWNLOAD NZSO ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Annual Report

G.69 Annual Report 2019 FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 NEW ZEALAND SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 1 2 Contents NZSO: Vision, Mission, and Values 2 Chair’s Preface 5 Artistic Overview 9 Organisational Structure 16 Governance Statement 17 Statement of Responsibility 19 Statement of Service Performance 20 Financial Statements 25 Independent Auditor’s Report 42 Organisational Health and Capability 45 The Board have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report for the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra for the year ended 31 December 2019. Laurence Kubiak Geoff Dangerfield Board Chair Board Member 31 August 2020 Audit Committee Member 31 August 2020 Vision and Mission Values THE VISION WHAT WE DO Providing world class musical experiences that We value excellent engagement inspire all New Zealanders. • We identify strongly with one another and with New Zealanders. achieved by • We ensure that our work is relevant to our audiences. THE MISSION • We communicate openly and honestly with one another and with New Zealanders. Deepening and expanding musical connections and engagement with our communities. HOW WE DO IT We value creative excellence through • We are passionate about our music and strive to share it widely. A NATIONAL FULLTIME • We are innovative and creative in all aspects FULL SIZE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA of our activities. which • We are inspired to be excellent in all our Performs to an international standard performances. is Excellent in performance HOW WE BEHAVE has We value excellent relationships Relevant and engaging programming, Reaches large and diverse audiences • We always act with fairness, honesty and transparency. and asserts • We trust, respect, acknowledge and Musical and artistic leadership. -

Ejournal Foreword

Research in New Zealand Performing Arts: Nga Mahi a Rehia no Aotearoa E-journal Foreword Tena koutou katoa! Over the past several years there have been a great many exciting developments in Aotearoa / New Zealand performing arts. One example is the recent prominence of New Zealand and success of New Zealanders in the realm of mainstream Hollywood blockbuster films, as evidenced by The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Last Samurai, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, and others. Such films, have seen this relatively small nation enjoy a profile in a global industry, which is disproportionate to the size of its populace. Of particular note in the case of the film industry are the successes of films based on local stories and culture. With the exception of the biographical, The World’s Fastest Indian (about NZ racer Burt Munro), most of the other NZ films that have done well in the last four years have been primarily based upon the stories, cultures, and experiences of Māori and Pacific Islanders,1 including Whale Rider, No. 2, River Queen, Sione’s Wedding, and the Oscar-nominated short film Two Cars, One Night. All of these have received much critical acclaim at home and abroad, and give some credence to the statement found on the New Zealand Film Commission’s website asserting that “it’s never been so hip to be brown.”2 Keeping in this same vein, if “brown” film, TV, music, dance, etc. have in the past been poorly supported and appreciated by New Zealand and the rest of the world, now, more than ever, it seems the tide has turned and their time has come. -

SONGS of BELLONA ISLAND (NA TAUNGUA 0 Mungiklj

Jane Mink Rossen SONGS OF BELLONA ISLAND (NA TAUNGUA 0 MUNGIKlj VOLUME ONE ,".~-,~~ '.f;4;41C'{it::?~..· " ........... Acta Ethnomusicologica Danica 4 Language and Culture of Rennell and Bellona Islands: Volume VI (NA TAUNGUA 0 MUNGIKI) -- £ , i • lit • .0,,~ 7nh4 !C..J ;1,1,", l. Acta Ethnomusicologica Danica 4 Forlaget Kragen, Copenhagen 1987 Language and Culture of Rennell and Bellona Islands: Volume VI SONGS OF BELLONA ISLAND (NA TAUNGUA 0 MUNGIKI) Volume One To my parents and children, and to the memory of Paul Sa'engeika, Joshua Kaipua, Sanga'eha and Tupe'uhi. "The sacred song goes back to the ancestors and forward to the descendants.... " (pese song) I hope that the Bellonese people will find a way to bring their own historical art and wisdom to this modern world, and tap the strength which comes from having one's own culture. Denne afhandling er af det filosofiske fakultet ved K0benhavns Universitet antaget til offentlig at forsvares for den filosofiske doktorgrad. KfJbenhavn, den 4. juni 1985 Michael Chestnutt h. a.decanus Danish Folklore Archives, Skrifter 5 Songs of Bellona Island (na taungua 0 Mungiki), Volume One 1987 Forlaget Kragen ApS ISBN 879806 36-8-5 COPYRIGHT © 1987 Jane Mink Rossen Cover photograph: The dance mako ngangi, 1974: Jane Mink Rossen CON TEN T 5, Volume One PART 1. Music in Traditional Life and Thought Chapter Page: Preface Introduction 1 Field Work 11 One: The Art of Music on Bellona 22 1.1 Status of music in the traditional culture 23 1.2 Poetry and language 26 Two: Musical Genres and Classification -

Contemporary New Zealand Piano Music

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Contemporary New Zealand Piano Music: Four Selected Works from Twelve Landscape Preludes: Landscape Prelude, the Street Where I Live, Sleeper and the Horizon from Owhiro Bay Joohae Kim Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC CONTEMPORARY NEW ZEALAND PIANO MUSIC: FOUR SELECTED WORKS FROM TWELVE LANDSCAPE PRELUDES: LANDSCAPE PRELUDE, THE STREET WHERE I LIVE, SLEEPER AND THE HORIZON FROM OWHIRO BAY By JOOHAE KIM A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 ! ! ! ! Joohae Kim defended this treatise on April 26, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Read Gainsford Professor Directing Treatise Evan Jones University Representative Joel Hastings Committee Member Heidi Louise Williams Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ! ""! ! ! Dedicated to my mother, Sunghae Cho (!"#) and my father, Keehyouk Kim ($%&) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! """! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to four New Zealand composers, Mr. Jack Body, Mr. John Psathas, Mr. Gareth Farr and Ms. Jenny McLeod. I would not even be able to have begun this research without their support. I enjoyed so much working with them; they were true inspirations for my research. My greatest thanks goes to my major professor, Dr. Read Gainsford, for his endless support and musical suggestions. -

The Festivalisation of Pacific Cultures in New Zealand: Diasporic Flow and Identity Within ‘A Sea of Islands’

The Festivalisation of Pacific Cultures in New Zealand: Diasporic Flow and Identity within ‘a Sea of Islands’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Otago Dunedin New Zealand Jared Mackley-Crump 2012 Abstract In the second half of the twentieth century, New Zealand witnessed a period of significant change, a period that resulted in dramatic demographic shifts. As a result of economic diversification, the New Zealand government looked to the Pacific (and to the at the time predominantly rural Māori population) to fill increasing labour shortages. Pacific Peoples began to migrate to New Zealand in large numbers from the mid-1960s and continued to do so until the mid-1970s, by which time changing economic conditions had impacted the country’s migration needs. At around this time, in 1976, the first major moment of the festivalisation of Pacific cultures occured. As the communities continued to grow and become entrenched, more festivals were initiated across the country. By 2010, with Pacific peoples making up approximately 7% of the population, there were twenty-five annual festivals held from the northernmost towns to the bottom of the South Island. By comparing the history of Pacific festivals and peoples in New Zealand, I argue that festivals reflect how Pacific communities have been transformed from small communities of migrants to large communities of largely New Zealand-born Pacific peoples. Uncovering the meanings of festivals and the musical performances presented within festival spaces, I show how notions of place, culture and identity have been changed in the process. Conceiving of the Pacific as a vast interconnected ‘Sea of Islands’ kinship network (Hau’ofa 1994), where people, trade, arts and customs have circulated across millennia, I propose that Pacific festivals represent the most highly visible public manifestations of this network operating within New Zealand, and of New Zealand’s place within it. -

'There's a Sound of Many Voices in the Camp and on the Track' –

‘There’s a Sound of Many Voices in the Camp and on the Track’ A Descriptive Analysis of Folk Music Collecting in New Zealand, 1955-1975 Michael Brown A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in Music at Victoria University, Wellington New Zealand April 2006 i Abstract During the period from 1955 to 1975 a group of individuals began the task of collecting folk music in New Zealand. This collecting was different from the earlier collecting of Maori music – it focussed mainly on English-language material felt to be the folk heritage of New Zealanders of European descent. The collectors gathered a valuable body of songs, verse and music, which was used in a variety of ways. Many individuals promoted the material to a wider public by performing music, recording albums and publishing song anthologies. Other collectors commenced the scholarly study of folk traditions in New Zealand. This thesis is a descriptive analysis of the work of seven individuals involved in the overall effort: Angela Annabell, Rona Bailey, Les Cleveland, Neil Colquhoun, Frank Fyfe, Phil Garland and Herbert Roth. It seeks to understand the enterprise from their point of view: how they conceived of ‘folk music’; their collecting methods; and the ways in which they promoted or studied what they had collected. To help situate and compare the achievement of each individual, their work is placed within the wider contexts of overseas folkloristic research, related study in New Zealand and the folk revival movement. The collecting in New Zealand was relatively short-lived but brought together a recognised canon of folk music. -

ICTM Study Group on Musics of Oceania Circular No. 39 We

ICTM Study Group on Musics of Oceania 15 March 1999 Circular No. 39 We welcome new member Howard Charles. See addresses below. ICTM 35th World Conference. Hiroshima. Japan. 19-25 August 1999 The business meeting of the Study Group on Musics of Oceania will be held during the World Conference, (tentatively scheduled for Tuesday, 24 August, 3:30pm). The agenda will include consideration of a proposal that our Study Group maintain a discography and a filmography/videography on the website being set up for all ICTM study groups by the new Study-Group Coordinator, Dr. Tilman Seebass; possibilities of website posting and/or email 'discussion list' format for the Circular; and other matters related to future operations of our group. Please see the enclosed questionnaire which I urge all members to return as promptly as possible. Our Study Group will be well represented in the World Conference through papers presented by our members: Barwick, Kaeppler, Konishi, Kurokawa, Marett, Moulin, Niles, Simon, Stillman, Wild. Several other Study Group members will present papers on non-Oceanic subjects and several will chair sessions. I strongly encourage all our members to go to Hiroshima for both the Conference and our Meeting. ICTM Study Group on Musics of Oceania Meeting. Hiroshima. Japan 26-27 August 1999 Plans are underway for a few special presentations and discussion of the announced themes--Agendas for Research in the Next Millennium; Pacific Island Music & Dance for and in Asia; New Video Documentation of Music & Dance--and, perhaps also, the role of culture centers. (I hope you will not be enticed to leave Hiroshima before our meeting to join the sightseeing tour to Kyoto arranged by the World Conference's Organizing Committee after our meeting date had been set.) Other past and forthcoming conferences. -

THE VOICES of TOKELAU YOUTH in NEW ZEALAND Na Mafialeo Onā Tupulaga Tokelau I Niu Hila

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington THE VOICES OF TOKELAU YOUTH IN NEW ZEALAND Na mafialeo onā Tupulaga Tokelau i Niu Hila By Paula Kele-Faiva A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Pacific Studies Victoria University of Wellington 2010 2 ABSTRACT Tokelau is a minority group within New Zealand‟s larger Pacific community. New Zealand has a special relationship with the three small and very isolated atolls groups which make up Tokelau. The Tokelauan population in New Zealand is nearly five times that of the homelands. As a contribution to the global „Youth Choices Youth Voices‟ study of youth acculturation, this research also contributes to the experiences of Pacific youth in New Zealand. The focus of this study is on Tokelauan youth and explores the perceptions of a group of Wellington based Tokelauan youth on their identity, sense of belonging, connectedness and hopes for the future. Also, the views of a group of Tokelauan elders are presented to set the background for the youth voices to be understood. The aim of this qualitative study was to capture the unheard voice of the Tokelauan youth, to explore their stories and experiences so that the information provided will inform policy and programme planning for Tokelauan youth, as well as Pacific and other minority groups in New Zealand. Using talanoa methodology, a combination of group māopoopoga and individual in depth interviews, valuable knowledge was shared giving insights into the experiences, needs and future aspirations of Tokelauan youth in New Zealand.