Dr Anthony (Tony) Turton Light Horse Regiment & National Intelligence Service Missing Voices Project Interviewed by Mike Cadman 26 & 28/04/08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dodannualreport20042005.Pdf

chapter 7 All enquiries with respect to this report can be forwarded to Brigadier General A. Fakir at telephone number +27-12 355 5800 or Fax +27-12 355 5021 Col R.C. Brand at telephone number +27-12 355 5967 or Fax +27-12 355 5613 email: [email protected] All enquiries with respect to the Annual Financial Statements can be forwarded to Mr H.J. Fourie at telephone number +27-12 392 2735 or Fax +27-12 392 2748 ISBN 0-621-36083-X RP 159/2005 Printed by 1 MILITARY PRINTING REGIMENT, PRETORIA DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 chapter 7 D E P A R T M E N T O F D E F E N C E A N N U A L R E P O R T 2 0 0 4 / 2 0 0 5 Mr M.G.P. Lekota Minister of Defence Report of the Department of Defence: 1 April 2004 to 31 March 2005. I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Defence. J.B. MASILELA SECRETARY FOR DEFENCE: DIRECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT FY 2004 - 2005 i contents T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S PAGE List of Tables vi List of Figures viii Foreword by the Minister of Defence ix Foreword by the Deputy Minister of Defence xi Strategic overview by the Secretary for Defence xiii The Year in Review by the Chief of the SA National Defence Force xv PART1: STRATEGIC DIRECTION Chapter 1 Strategic Direction Introduction 1 Aim 1 Scope of the Annual Report 1 Strategic Profile 2 Alignment with Cabinet and Cluster Priorities 2 Minister of Defence's Priorities for FY2004/05 2 Strategic Focus 2 Functions of the Secretary for Defence 3 Functions of the Chief of the SANDF 3 Parys Resolutions 3 Chapter -

Download PDF Van Tekst

Voortgang. Jaargang 18 bron Voortgang. Jaargang 18. 1999 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_voo004199901_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 7 Die navolging van Guido Gezelle se ‘Twee horsen’ deur Jan F.E. Celliers Etienne Britz Abstract - In a previous issue of this journal (Voortgang XVI, 1996: 91-113), J.D.F. van Halsema traced the argument which evolved in 1913 and 1914 between the Dutch literary critic Albert Verwey on the one side, and South African supporters of the advancement of Afrikaans as a cultural language on the other. The argument involved the alleged merits of the Afrikaans poet C. Louis Leipoldt and the corresponding demerits of Leipoldt's contemporaries Jan F.E. Celliers and Totius. In his periodical De Beweging, Verwey lauded Leipoldt's so-called ‘spraak’ (literally: - ‘speech’), by which he meant Leipoldt's lack of contrivance; his natural talent and originality as a poet. Leipoldt was clearly well-read, according to Verwey, but his erudition did not have a conspicuous regulatory effect on his writing. Celliers and Totius, however, produced ‘schriftuur’ (writing according to set rules), because they employed the well-known rhetorical devices of nineteenth century European poetry and their poems were often recognizable imitations of English, Dutch, French or German originals. They reiterated the European register, whereas Leipoldt deviated from this register with his uniquely South African ‘speech’. The denunciation of Celliers and Totius alarmed the ‘taalstryders’ (language fighters) of the so-called Second Afrikaans Language Movement in South Africa because it denied Afrikaans two artists who seemed to lend new refinement, dignity and depth to its advance as a civilized language. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

SADF Military Operations

SADF Military Operations 1975 -1989 Contents 1 List of operations of the South African Border War 1 2 Operation Savannah (Angola) 3 2.1 Background .............................................. 3 2.2 Military intervention .......................................... 4 2.2.1 Support for UNITA and FNLA ................................ 5 2.2.2 Ruacana-Calueque occupation ................................ 5 2.2.3 Task Force Zulu ........................................ 5 2.2.4 Cuban intervention ...................................... 6 2.2.5 South African reinforcements ................................. 6 2.2.6 End of South African advance ................................ 6 2.3 Major battles and incidents ...................................... 6 2.3.1 Battle of Quifangondo .................................... 7 2.3.2 Battle of Ebo ......................................... 7 2.3.3 “Bridge 14” .......................................... 7 2.3.4 Battle of Luso ......................................... 7 2.3.5 Battles involving Battlegroup Zulu in the west ........................ 8 2.3.6 Ambrizete incident ...................................... 8 2.4 Aftermath ............................................... 8 2.5 South African order of battle ..................................... 9 2.6 Association .............................................. 9 2.7 Further reading ............................................ 9 2.8 References ............................................... 9 3 Operation Bruilof 13 3.1 Background ............................................. -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

Procurement Politics, Technology Transfer and the Challenges of Collaborative MBT Projects in the NATO Alliance Since 1945

A Standard European Tank? Procurement Politics, Technology Transfer and the Challenges of Collaborative MBT Projects in the NATO Alliance since 1945 Mike Cubbin School of Arts and Media Salford University Submitted to the University of Salford in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 Abstract International cooperation in weapons technology projects has long been a feature of alliance politics; and, there are many advantages to both international technology transfer and standardisation within military alliances. International collaboration between national defence industries has produced successful weapon systems from technologically advanced fighter aircraft to anti-tank missiles. Given the success of many joint defence projects, one unresolved question is why there have been no successful collaborative international main battle tank (MBT) projects since 1945. This thesis seeks to answer this question by considering four case studies of failed attempts to produce an MBT through an international collaborative tank project: first and second, the Franco-German efforts to produce a standard European tank, or Euro-Panzer (represented by two separate projects in 1957-63 and 1977- 83); third, the US-German MBT-70 project (1963-70); and, fourth, the Anglo-German Future Main Battle Tank, or KPz3 (1971-77). In order to provide an explanation of the causes of failure on four separate occasions, the analysis includes reference to other high-technology civilian and military joint projects which either succeeded, -

The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 16, Nr 2, 1986. http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za The Role of Non-Whites in the South African Defence Force by Cmdt C.J. N6thling* assisted by Mrs L. 5teyn* The early period for Blacks, Coloureds and Indians were non- existent. It was, however, inevitable that they As long ago as 1700, when the Cape of Good would be resuscitated when war came in 1939. Hope was still a small settlement ruled by the Dutch East India Company, Coloureds were As war establishment tables from this period subject to the same military duties as Euro- indicate, Non-Whites served as separate units in peans. non-combatant roles such as drivers, stretcher- bearers and batmen. However, in some cases It was, however, a foreign war that caused the the official non-combatant edifice could not be establishment of the first Pandour regiment in maintained especially as South Africa's shortage 1781. They comprised a force under white offi- of manpower became more acute. This under- cers that fought against the British prior to the lined the need for better utilization of Non-Whites occupation of the Cape in 1795. Between the in posts listed on the establishment tables of years 1795-1803 the British employed white units and a number of Non-Whites were Coloured soldiers; they became known as the subsequently attached to combat units and they Cape Corps after the second British occupation rendered active service, inter alia in an anti-air- in 1806. During the first period of British rule craft role. -

2020 Convention Attendee List 201007.Xlsx

Title First Name Last Name Organisation Ms Maimoonah Abed Liberty Corporate Consultants & Actuaries Ms Hilda Abraham Old Mutual Mr Trevor Abromowitz Omig Ms Yvonne Acker Old Mutual Mrs Michelle Acton Old Mutual Mrs Fareeya Adam Momentum Mr Obaidullah Adam Hannover Life Re Africa Miss Jessi Africa Liberty Actuarial Development Programme Mr Shamim Aghdasi Old Mutual Mr Christiaan Ahlers Prudential Authority Mr Rimaan Ahmed Momentum Multiply Mr Edward Alant EDGE Actuarial Consulting Mr Sanesh Albert Old Mutual Mr Pieter Albertyn Momentum Metropolitan Mr Yaaseen Albertyn Momentum Metropolitan Life Mrs Lizelle Alexander‐Petersen Mediclinic Mr Joshua Allers Discovery Life Mr Nirmal Amdawadi Momentum Mr John Anderson Alexander Forbes Investments Mr Michael Anderson Discovery Life Mrs Elizabeth Fredrika Andrag Sanlam Mr Craig Andrews Discovery Ms Janice Angove Mrs Petro Appelo Hannover Life Re Africa Mr Victor Asiwe Discovery Insure Mrs Jeanine Astrup Cadiant Partners Actuarial & Consulting Solutions Mr Andy Atkins Ernst & Young Advisory Services Ms Susan Atkinson Mr Robert Attwell Mr Quintin J Augustine PPS Insurance Company Mr Bruce Austin Liberty Life Mr Conrad Backeberg Actuarial Society of South Africa Miss Fatima Badat Sanlam Mr Michael Badenhorst Cadiant Partners Consultants & Actuaries Mr Nick Badenhorst Ips Health And Wellness Mr Adhir Badul Discovery Central Services Mrs Azelle Baker Deloitte Mr Dinagren Balakrishnan Alexander Forbes Life Ms Gavina Balasundran Liberty Life Mr Caesar Balona QED Actuaries & Consultants Mr Hungalani Baloyi -

YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30Pm

#BAMNextWave #YouUsWeAll Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30pm Running time: one hour & 20 minutes, no intermission Music by Shara Worden Text, direction, and design by Andrew Ondrejcak B.O.X. (Baroque Orchestration X) Season Sponsor: Leadership support for opera at BAM provided by Aashish & Dinyar Devitre Endowment funding has been provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Opera and Music-Theater Major support for opera at BAM provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust YOU US WE ALL CAST HOPE Shara Worden VIRTUE Helga Davis LOVE Martin Gerke DEATH Bernhard Landauer TIME Carlos Soto B.O.X. ENSEMBLE A Continuo/Rythm Section Theorbo, artistic direction Pieter Theuns Harpsichord, organ Anthony Romaniuk Baroque harp Jutta Troch Drums, percussion Mattijs Vanderleen An Alta Capella of Winds Cornett, flutes Lambert Colson Cornett, trumpet Jon Birdsong Sackbut (baroque trombone) Liza Malamut A Consort of Viols Treble viol, bass viol Liam Byrne Bass viol Pieter Vandeveire Violone Christine Sticher PRODUCTION CREDITS Stage, light, costume, projection design Andrew Ondrejcak Choreographer Seth Stewart Williams Production dramaturg Anne Seiwerath Executive producer/tour management ArKtype/Thomas O. Kriegsmann Production manager/lighting director Davison Scandrett Production stage manager Valerie Oliveiro Assistant stage manager Nina Segal Video design consultant Andrew Bauer Video supervisor Tei Blow Co-lighting design Lutz Deppe Co-costume design Zane Philstrom Assistant director Cecile Tonizzo Sound design David Schnirman/Hear No Evil Wig design Rick Gradone Make-up design Marco Campos Assistant, costumes and wardrobe Baille Younkman Assistant, costumes Julie Michaels Production assistant Veerle Van Rossom YOU US WE ALL is commissioned by B.O.X. -

Canada Gouvernementaux Canada

Public Works and Government Services Travaux publics et Services 1 1 Canada gouvernementaux Canada RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: SIMULATION ENTITY MODELS Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception des soumissions Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amendment No. - N° modif. - TPSGC W8475-135211/B 006 11 Laurier St. / 11, rue Laurier Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client Date Place du Portage, Phase III Core 0A1 / Noyau 0A1 W8475-135211 2014-03-20 Gatineau GETS Reference No. - N° de référence de SEAG Quebec PW-$$EE-048-26597 K1A 0S5 Bid Fax: (819) 997-9776 File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME 048ee.W8475-135211 Time Zone SOLICITATION AMENDMENT Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin at - à 02:00 PM Fuseau horaire MODIFICATION DE L'INVITATION Eastern Daylight Saving on - le 2014-04-25 Time EDT F.O.B. - F.A.B. The referenced document is hereby revised; unless otherwise indicated, all other terms and conditions of the Solicitation Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: remain the same. Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Friesen, Manon 048ee Ce document est par la présente révisé; sauf indication contraire, Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX les modalités de l'invitation demeurent les mêmes. (819) 956-1161 ( ) ( ) - Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: Comments - Commentaires Vendor/Firm Name and Address Instructions: See Herein Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Instructions: Voir aux présentes Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Delivery Offered - Livraison proposée Vendor/Firm Name and Address Raison sociale et adresse du fournisseur/de l'entrepreneur Issuing Office - Bureau de distribution Telephone No. -

![THE HISTORY of the PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3136/the-history-of-the-pietersburg-polokwane-jewish-community-by-charlotte-wiener-submitted-in-fulfillment-of-the-requirements-883136.webp)

THE HISTORY of the PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements

THE HISTORY OF THE PIETERSBURG [POLOKWANE] JEWISH COMMUNITY by CHARLOTTE WIENER Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject JUDAICA at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MR CEDRIC GINSBERG NOVEMBER 2006 SUMMARY Jews were present in Pietersburg [Polokwane] from the time of its establishment in 1868. They came from Lithuania, England and Germany. They were attracted by the discovery of gold, land and work opportunities. The first Jewish cemetery was established on land granted by President Paul Kruger in 1895. The Zoutpansberg Hebrew Congregation, which included Pietersburg and Louis Trichardt was established around 1897. In 1912, Pietersburg founded its own congregation, the Pietersburg Hebrew Congregation. A Jewish burial society, a benevolent society and the Pietersburg-Zoutpansberg Zionist Society was formed. A communal hall was built in 1921 and a synagogue in 1953. Jews contributed to the development of Pietersburg and held high office. There was little anti-Semitism. From the 1960s, Jews began moving to the cities. The communal hall and minister’s house were sold in 1994 and the synagogue in 2003. Only the Jewish cemetery remains in Pietersburg. 10 key words: 1] Pietersburg [Polokwane] 2] Zoutpansberg 3] Anglo-Boer War 4] Jew 5] Synagogue 6] Cemetery 7] Rabbi 8] Hebrew 9] Zionist 10] Anti-Semitism ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following: Mr Cedric Ginsberg, my supervisor, for his invaluable assistance, patience and meticulous corrections The late Mr Wally Levy for his information concerning families and events in the Northern Transvaal. His prodigious memory was extremely helpful to me My husband Dennis and children Janine, Elian and Mandy, for their patience with my obsession to finish this thesis. -

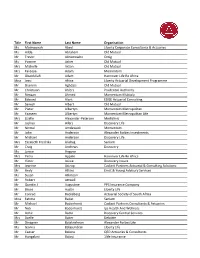

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite