Geting Tau Pathology Or Other Patients with CBS Have Been Studied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

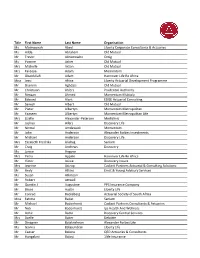

2020 Convention Attendee List 201007.Xlsx

Title First Name Last Name Organisation Ms Maimoonah Abed Liberty Corporate Consultants & Actuaries Ms Hilda Abraham Old Mutual Mr Trevor Abromowitz Omig Ms Yvonne Acker Old Mutual Mrs Michelle Acton Old Mutual Mrs Fareeya Adam Momentum Mr Obaidullah Adam Hannover Life Re Africa Miss Jessi Africa Liberty Actuarial Development Programme Mr Shamim Aghdasi Old Mutual Mr Christiaan Ahlers Prudential Authority Mr Rimaan Ahmed Momentum Multiply Mr Edward Alant EDGE Actuarial Consulting Mr Sanesh Albert Old Mutual Mr Pieter Albertyn Momentum Metropolitan Mr Yaaseen Albertyn Momentum Metropolitan Life Mrs Lizelle Alexander‐Petersen Mediclinic Mr Joshua Allers Discovery Life Mr Nirmal Amdawadi Momentum Mr John Anderson Alexander Forbes Investments Mr Michael Anderson Discovery Life Mrs Elizabeth Fredrika Andrag Sanlam Mr Craig Andrews Discovery Ms Janice Angove Mrs Petro Appelo Hannover Life Re Africa Mr Victor Asiwe Discovery Insure Mrs Jeanine Astrup Cadiant Partners Actuarial & Consulting Solutions Mr Andy Atkins Ernst & Young Advisory Services Ms Susan Atkinson Mr Robert Attwell Mr Quintin J Augustine PPS Insurance Company Mr Bruce Austin Liberty Life Mr Conrad Backeberg Actuarial Society of South Africa Miss Fatima Badat Sanlam Mr Michael Badenhorst Cadiant Partners Consultants & Actuaries Mr Nick Badenhorst Ips Health And Wellness Mr Adhir Badul Discovery Central Services Mrs Azelle Baker Deloitte Mr Dinagren Balakrishnan Alexander Forbes Life Ms Gavina Balasundran Liberty Life Mr Caesar Balona QED Actuaries & Consultants Mr Hungalani Baloyi -

YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30Pm

#BAMNextWave #YouUsWeAll Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer YOU US WE ALL BAM Harvey Theater Nov 11—14 at 7:30pm Running time: one hour & 20 minutes, no intermission Music by Shara Worden Text, direction, and design by Andrew Ondrejcak B.O.X. (Baroque Orchestration X) Season Sponsor: Leadership support for opera at BAM provided by Aashish & Dinyar Devitre Endowment funding has been provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fund for Opera and Music-Theater Major support for opera at BAM provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust YOU US WE ALL CAST HOPE Shara Worden VIRTUE Helga Davis LOVE Martin Gerke DEATH Bernhard Landauer TIME Carlos Soto B.O.X. ENSEMBLE A Continuo/Rythm Section Theorbo, artistic direction Pieter Theuns Harpsichord, organ Anthony Romaniuk Baroque harp Jutta Troch Drums, percussion Mattijs Vanderleen An Alta Capella of Winds Cornett, flutes Lambert Colson Cornett, trumpet Jon Birdsong Sackbut (baroque trombone) Liza Malamut A Consort of Viols Treble viol, bass viol Liam Byrne Bass viol Pieter Vandeveire Violone Christine Sticher PRODUCTION CREDITS Stage, light, costume, projection design Andrew Ondrejcak Choreographer Seth Stewart Williams Production dramaturg Anne Seiwerath Executive producer/tour management ArKtype/Thomas O. Kriegsmann Production manager/lighting director Davison Scandrett Production stage manager Valerie Oliveiro Assistant stage manager Nina Segal Video design consultant Andrew Bauer Video supervisor Tei Blow Co-lighting design Lutz Deppe Co-costume design Zane Philstrom Assistant director Cecile Tonizzo Sound design David Schnirman/Hear No Evil Wig design Rick Gradone Make-up design Marco Campos Assistant, costumes and wardrobe Baille Younkman Assistant, costumes Julie Michaels Production assistant Veerle Van Rossom YOU US WE ALL is commissioned by B.O.X. -

Spring 2020 B-M-S

COMMENCEMENT THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL GRADUATION LIST While every effort is made to ensure accuracy in this commencement program, printing deadlines may result in omission of some names and use of names of persons not completing graduation requirements as intended. This printed program, therefore, should not be used to determine a student’s academic or degree status. The university’s official registry for conferral of degrees is the student’s permanent academic record as reflected on the student’s transcript, maintained by the Office of the University Registrar. Commencement SPRING 2020 Greetings from the President n behalf of the University of Florida, our faculty and our entire university community, I would like to extend my deepest congratulations to you, the Graduates of 2020. OI celebrate your remarkable accomplishment in earning a degree from one of the world’s leading research institutions. I applaud you for the education you have received, for honing your creative, scientific, or analytical skills and for your achievements as students. I join you in thanking your professors, advisors and family and friends for their contributions to your success. This is a time for celebration, but also for reflection on your future. I am confident that the knowledge and experience you gained as a UF student will serve you well regardless of your career or how you choose to invest your life. The university has benefited from your active engagement and contributions to your classes, programs of study and your peers, and we are grateful for your time here. We hope you will recall these years fondly, and that you will remain connected to UF as active members of our distinguished alumni. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

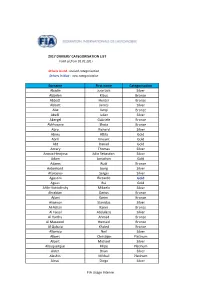

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Collèges Colleges

Disclosure for 2012 under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996 Colleges This category includes Ontario Colleges. Divulgation pour 2012 en vertu de la Loi de 1996 sur la divulgation des traitements dans le secteur public Collèges Cette catégorie contient les collèges de l’Ontario. Taxable Surname/Nom de Given Name/ Salary Paid/ Benefits/ Employer/Employeur famille Prénom Position/Poste Traitement Avant. impos. Algonquin College ABBAS SADIQ Professor $102,185.98 $119.88 Algonquin College AGATE JEFFERY MICHAEL Manager, Counselling and Testing Services$104,656.60 $335.15 Algonquin College AL-AZZAWI ABDUL Professor $103,133.47 $185.88 Algonquin College ALLAN GAIL Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College ALLEN IAN D. Professor $104,140.79 $119.88 Algonquin College ALMUHTADI WAHAB Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College ANDERSON DANIEL Professor $102,185.98 $119.88 Algonquin College ANDERSON MICHAEL Professor $104,573.33 $185.88 Algonquin College ASSELIN JACQUELINE Professor $103,539.54 $185.88 Algonquin College AUBIN JERRY A. Professor $108,961.50 $119.88 Algonquin College AUBUT JOANN Dean, Academic Development $139,301.88 $445.83 Algonquin College BAIN RODNEY Professor $102,269.74 $185.88 Algonquin College BALASEVICIUS DEBRA Chair, Health and Community Studies Department$118,961.88 $389.52 Algonquin College BALLARD MICHAEL Professor $104,893.10 $185.88 Algonquin College BARKER GERRY A. Vice President, Human Resources $204,434.22 $585.94 Algonquin College BAUCOM ALFRED Professor $102,216.63 $119.88 Algonquin College BELANGER MARIA Professor $103,611.47 $119.88 Algonquin College BERRY LYNN M. Professor $108,381.94 $185.88 Algonquin College BEST DAVE Professor $100,506.36 $185.88 Algonquin College BONANG COLIN Associate Director, Safety, Security and Emergency Management$108,989.51 $352.32 Algonquin College BOND ANTHONY R. -

Parkinson Disease from Mendelian Forms to Genetic Susceptibility: New Molecular Insights Into the Neurodegeneration Process

Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-018-0587-4 REVIEW PAPER Parkinson Disease from Mendelian Forms to Genetic Susceptibility: New Molecular Insights into the Neurodegeneration Process Amin Karimi‑Moghadam1 · Saeid Charsouei2 · Benjamin Bell3 · Mohammad Reza Jabalameli1,3 Received: 12 February 2018 / Accepted: 20 April 2018 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract Parkinson disease (PD) is known as a common progressive neurodegenerative disease which is clinically diagnosed by the manifestation of numerous motor and nonmotor symptoms. PD is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with both familial and sporadic forms. To date, researches in the field of Parkinsonism have identified 23 genes or loci linked to rare monogenic familial forms of PD with Mendelian inheritance. Biochemical studies revealed that the products of these genes usually play key roles in the proper protein and mitochondrial quality control processes, as well as synaptic transmission and vesicular recycling pathways within neurons. Despite this, large number of patients affected with PD typically tends to show sporadic forms of disease with lack of a clear family history. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) meta-analyses on the large sporadic PD case–control samples from European populations have identified over 12 genetic risk factors. However, the genetic etiology that underlies pathogenesis of PD is also discussed, since it remains unidentified in 40% of all PD-affected cases. Nowadays, with the emergence of new genetic techniques, international PD genomics consortiums and public online resources such as PDGene, there are many hopes that future large-scale genetics projects provide further insights into the genetic etiology of PD and improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic clinical trial designs. -

2017 Drivers Categorisation List Final List 081217.Xlsx

2017 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Valid as from 01.01.2017 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Bronze Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Gold Adams Rudi Bronze Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin‐Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al‐Azhari Karim Bronze Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Bronze Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alessi Diego Silver FIA Usage Interne Surname First name Categorisation Alexander Iradj Silver Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al‐Thani Abdulrahman Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen Uwe Gold Amado Ulric Gold Amaduzzi Davide Bronze Amaral Miguel Bronze Amberg Zoel Gold Amici Andrea Silver Ammermüller Michael Gold Amos Eugenio Silver Amstutz Adrian Bronze Anapoli Giovanni Bronze Andersen -

L'étoile Étrange, Année 2018, Numéro 12

L’étoile étrange #12 – Semaine du 15 septembre 2018 1 Science-fiction, Fantastique, Aventure & Fantasy Interview Alexandre S. Garcia Convention Mondiale de SF Dossier Shadowhunters 2016 S1+S2+S3A Numéro 12 - gratuit Tous droitsSemaine réservés images du 15 et septembre textes 2018 2018 L’étoile étrange #12 – Semaine du 15 septembre 2018 2 Édito La Forme de la Fantasy Urbaine. Depuis le 19ème siècle, le Fantastique Gothique s’est dopé à la frénésie spirite de la Belle époque, puis aux monstres de la MGM et enfin aux grandes épopées de Haute Fantasy à la Seigneur des Anneaux, C’est Anne Rice qui ouvre le bal avec son Entretien avec un Vampire ; Joss Whedon avec Buffy contre le vampire a dopé le genre grâce aux recettes tout droit sorties des jeux de rôles des années 1980 ; puis Charlaine Harris a mené avec le cocktail à l’eau de rose épicé True Blood, d’abord en romans puis adaptés puis sur HBO par Allan Ball. Enfin Stephenie Meyer a récolté les lauriers en faisant scintiller les vampires en plein soleil et en rejouant le grand air de la frustration sexuelle sans bain de sang, transformant au passage le cercueil de Bram Stocker en lessiveuse : les monstres sont devenus (plus ou moins) gentils, ou tout du moins, ils souffrent sincèrement quand ils vous tuent. Lorsque Star Trek la série télévisée parait dans les années 1960, les (futures) romancières de Science-fiction s’exclament : « si ce n’est que ça, écrire de la Science-fiction, alors je peux en faire autant ! ». Et les fans (surtout féminines) des amours torrides entre le capitaine James T. -

Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: a Mixed-Methods Approach on Training Design and Outcome Assessment

IUL School of Social Sciences Department of Social and Organizational Psychology Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: A mixed-methods approach on training design and outcome assessment Nuno Vladimiro Pereira Ramos Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Psychology Specialty in Social Psychology Supervisor: Carla Marina Madureira de Matos Moleiro, Assistant Professor ISCTE - Lisbon University Institute, Lisboa, Portugal Setembro, 2016 ii IUL School of Social Sciences Department of Social and Organizational Psychology Intercultural Competence in Conflict Mediation: A mixed-methods approach on training design and outcome assessment Nuno Vladimiro Pereira Ramos Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Psychology Specialty in Social Psychology Jury: Ph.D. Isabel Correia, Associate Professor at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Ana Maria Carneiro da Costa e Silva, Assistant Professor at Universidade do Minho, Portugal Ph.D. Carla Marina Madureira de Matos Moleiro, Assistant Professor at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Christin-Melanie Vauclair, FCT Researcher at ISCTE-IUL, Portugal Ph.D. Pedro Fernando Silva da Cunha, Associate Professor at Universidade Fernando Pessoa, Portugal Ph.D. Tiago Guedes do Nascimento Neves, Assistant Professor at Universidade do Porto, Portugal Julho, 2016 iii iv The present work was sponsored by a Doctoral Grant (Ref. SFRH/BD/76334/2011) of the Portuguese Science and Technology Foundation v vi Agradecimentos Algum do conhecimento que adquiri está escrito nas palavras desta tese. O final de percurso que se expressa neste documento, ritual e simbólico, não revela totalidade da experiência, consciência e sentimentos vividos. A riqueza que comigo fica é inestimável. -

Google Has Had More Murdered and Strangely Dead Employees Than Almost Any Other U.S

Google Has Had More Murdered And Strangely Dead Employees Than Almost Any Other U.S. Company Google Has Had More Murdered And Strangely Dead Employees Than Almost Any Other U.S. Company CIA-Front Google seems to get it's people killed quit a bit, and it is not just a math odds issue. Google employee found dead in San Francisco Bay A woman whose body was found in the water along the San Francisco Bay Trail in Sunnyvale, California was identified as a Google employee by the company Monday. Chuchu Ma, 23, was found dead half ⦠https://www.rawstory.com/2017/12/google-employee-found-dead-in-san... 23-year-old Google employee found dead in San Francisco Bay 4 Ex-NFL Network employee alleges sexual misconduct by former players in lawsuit. 5 Cecil Parkinson's daughter is found dead at 57. 7 San Francisco mayor dies suddenly at 65. 8 GoogleStoryboard turns your videos into comic strips. gizmorati.com/2017/12/13/23-year-old-google-employee-fo NYC Google employee killed jogging in Massachusetts - NY ... A Google employee from New York City was killed while jogging in Massachusetts over the weekend â a murder eerily reminiscent of the slaying of Karina ... nydailynews.com/news/national/homicide-probe-opened-nyc-g... Vanessa Marcotte: Google Employee Killed and Sexually ... A 27-year-old Google employee who was found dead in the woods on Sunday had been stripped naked and partially burned,⦠people.com/crime/vanessa-marcotte-google-employee-ki... Google Employee, 27, Found Dead Near Mother's Home in ..