Techniques and Best Practices for Corporate Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talent Agenting in the Age of Conglomerates

6 Talent Agenting in the Age of Conglomerates Violaine Roussel “Now, everything in the talent agency business is different forever,” commented a talent agent I interviewed after the announcement, in late 2013, of the acquisi- tion of the sports marketing giant IMG (International Management Group) by the major agency WME (William Morris Endeavor). Indeed, in the past decade, Hollywood talent agencies have had to undergo drastic changes, for which they are also largely responsible. These changes are intrinsically connected to transforma- tions that have simultaneously affected and been generated by the studios, who are the agencies’ counterparts on the production side. This organizational mutation creates consequences in creative terms: it directly affects what “doing one’s job” as an agent means and, inseparably and subsequently, how agents contribute to making cultural products and artistic careers. In a tumultuous time of rapid pro- fessional reconfiguration, work situations feel more precarious to creative work- ers and, inseparably, more uncertain to their agents. This chapter addresses such transformations. Talent representatives in the United States are divided into four main types of professionals: talent agents, managers, publicists, and entertainment lawyers. Unlike managers, who have only recently developed as an organized occupa- tion, agents are closely regulated by the state in which they work. They also hold a legal monopoly over the right to seek and procure employment for their clients, a service for which the agency receives 10 percent of the amount negotiated in the artist’s contracts. Agents scout and “sign” talent (although not always in formal written form, especially in the large agencies), work at placing them in jobs, and negotiate deals with producers and studios. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Off the Record

About the Center for Public Integrity The CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY, founded in 1989 by a group of concerned Americans, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, tax-exempt educational organization created so that important national issues can be investigated and analyzed over a period of months without the normal time or space limitations. Since its inception, the Center has investigated and disseminated a wide array of information in more than sixty Center reports. The Center's books and studies are resources for journalists, academics, and the general public, with databases, backup files, government documents, and other information available as well. The Center is funded by foundations, individuals, revenue from the sale of publications and editorial consulting with news organizations. The Joyce Foundation and the Town Creek Foundation provided financial support for this project. The Center gratefully acknowledges the support provided by: Carnegie Corporation of New York The Florence & John Schumann Foundation The John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation The New York Community Trust This report, and the views expressed herein, do not necessarily reflect the views of the individual members of the Center for Public Integrity's Board of Directors or Advisory Board. THE CENTER FOR PUBLIC INTEGRITY 910 17th Street, N.W. Seventh Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 Telephone: (202) 466-1300 Facsimile: (202)466-1101 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2000 The Center for Public Integrity All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from The Center for Public Integrity. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

American Broadcasting Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search for the Australian TV Network, See Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Scholarship applications are invited for Wiki Conference India being held from 18- <="" 20 November, 2011 in Mumbai. Apply here. Last date for application is August 15, > 2011. American Broadcasting Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search For the Australian TV network, see Australian Broadcasting Corporation. For the Philippine TV network, see Associated Broadcasting Company. For the former British ITV contractor, see Associated British Corporation. American Broadcasting Company (ABC) Radio Network Type Television Network "America's Branding Broadcasting Company" Country United States Availability National Slogan Start Here Owner Independent (divested from NBC, 1943–1953) United Paramount Theatres (1953– 1965) Independent (1965–1985) Capital Cities Communications (1985–1996) The Walt Disney Company (1997– present) Edward Noble Robert Iger Anne Sweeney Key people David Westin Paul Lee George Bodenheimer October 12, 1943 (Radio) Launch date April 19, 1948 (Television) Former NBC Blue names Network Picture 480i (16:9 SDTV) format 720p (HDTV) Official abc.go.com Website The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcasting television network. Created in 1943 from the former NBC Blue radio network, ABC is owned by The Walt Disney Company and is part of Disney-ABC Television Group. Its first broadcast on television was in 1948. As one of the Big Three television networks, its programming has contributed to American popular culture. Corporate headquarters is in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City,[1] while programming offices are in Burbank, California adjacent to the Walt Disney Studios and the corporate headquarters of The Walt Disney Company. The formal name of the operation is American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and that name appears on copyright notices for its in-house network productions and on all official documents of the company, including paychecks and contracts. -

The Methods Used to Secure Monetary Restitution

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 25, Issue 6 2001 Article 11 The Methods Used to Secure Monetary Restitution Transcripts∗ ∗ Copyright c 2001 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj The Methods Used to Secure Monetary Restitution Transcripts Abstract Record of panel discussion of the methods used to secure monetary restitution for Holocaust survivors and their heirs. Panelists discussed class action suits brought on behalf of survivors and the use of large-scale litigation to win monetary restitution. THE METHODS USED TO SECURE MONETARY RESTITUTION NOVEMBER 1, 2001 MODERATOR: Menachem Z. Rosensaft, Esq., Partner,Ross & Hardies* PANELISTS: Michael Geier, Deputy Director Generalfor Legal Affairs, German Ministry of Foreign Relations** Samuel J. Dubbin, Esq., Dubbin & Kravetz, Lead counsel in class action, South FloridaHolocaust Survivors Coalition*** H. Carl McCall, Comptroller, New York Statet Gideon Taylor, Executive Vice-President, Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, Inc. tt * Menachem Rosensaft is a partner at Ross & Hardies in New York, concentrating in international, securities, and general commercial litigation. He is a former Executive Vice President of the Jewish Renaissance Foundation, Inc., the Founding Chair of the International Network of Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors, and a former Na- tional President of the Labor Zionist Alliance. He is a member of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council's Executive Committee and a former Chair of its Content Committee and its Collections and Acquisitions Committee. An officer of the Park Ave- nue Synagogue in New York City, Mr. Rosensaft has written numerous articles for the New York Times, The Washington Post, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, the Jerusalem Post, and other publications. -

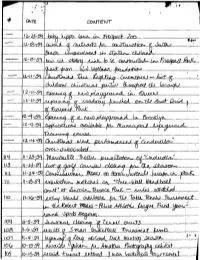

-Fo Oc Cs>Fiifr[Tftk<L- — Lof <R

, -fo Oc Cs>fiifr[tfTk<l- — Lof <r - : OXAK" — *5h(VF 6&i-f[/N3 uUPcflUY- J[« (JobL 3 %OAArLdc Mk/J /\ifaxir\Q fU> fbbxJ JUtkLsMc •» • 3 • \HxKxapai tfom pxrz. 5(o '<3>^ 55 5\ 5o (o-3-&\ fa tlJt Brot&* {) 5-22- 45 . c^ J .^^"io^U; 1&uuu^ajp<& CM-M^cyL5ta^ l i /cto^TLT. 6LO^ h&cQtyOte 51 . a -t 15* 35 <?4 u S3 •52. U -CjLl€hj01&-- Iv3l ^tcL?U J^UMj^tO^ zi ^ _.Ei-ciw_p4#_ QoU_. GIMJX ^c^co6 &cJ._^st. Z3 C^dLG— Cr?. fihfoJ^dtf'Gsi 2.2, ^ (jo Z( 2O Q 16 w 17 i ^ 15 4-2-5? <fl 13 II -uSj-f <n. fads - Ste&ttelL TcujrNztrtLti-. .. IP.. of q ..s. - past _ i A 1-13- Q od. .c?_ ttCJL 3 a 2 (-15-59 u % 7 i* DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1959 l-l-l-60M-707199(58) 114 The Department of Parks announces that a •baby- female hippopotamus weighing approximately 70 lbs. was born on November 24, 1959, at the Prospect Park &oo in Brooklyn. The mother, Betsy, now 9 years old, arrived at the Prospect Park &oo on September 8, 1953, and the sire, "Dodger", was 3 years old v/hen he arrived in 1951. However, "Dodger" passed away on October 8, 1959, and will not be around to hand out cigars. The new offspring has been named "'Annie". N.B. s Press photographs may be taken at tine* 12/23/59 DEPARTMEN O F PA R K S ARSENAL, CENTRAL PARK REGENT 4-1000 FOR RELEASE SUHDAY, D5CBMHBR 20, 1959 M-l-60M-529Q72(59) 114 The Borough President of Richmond and the Department of Parks announce the award of contracts, in the amount of $2,479,487, for the second stage of construction of the South Beach improvement in Staten Islitnd. -

Brazil-United States

Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue Created in June 2006 as part of the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program, the BRAZIL INSTITUTE strives to foster informed dialogue on key issues important to Brazilians and to the Brazilian-U.S. relationship. We work to promote detailed analysis of Brazil’s public policy and advance Washington’s understanding of contemporary Brazilian developments, mindful of the long history that binds the two most populous democracies in the Americas. The Institute honors this history and attempts to further bilateral coop- eration by promoting informed dialogue between these two diverse and vibrant multiracial societies. Our activities include: convening policy forums to stimulate nonpartisan reflection and debate on critical issues related to Brazil; promoting, sponsoring, and disseminating research; par- ticipating in the broader effort to inform Americans about Brazil through lectures and interviews given by its director; appointing leading Brazilian and Brazilianist academics, journalists, and policy makers as Wilson Center Public Policy Scholars; and maintaining a comprehensive website devoted to news, analysis, research, and reference materials on Brazil. Paulo Sotero, Director Michael Darden, Program Assistant Anna Carolina Cardenas, Program Assistant Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org/brazil ISBN: 978-1-938027-38-3 Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue May 11 – 13, 2011 Brazil-United States Judicial Dialogue Foreword ffirming the Rule of Law in a historically unequal and unjust Asociety has been a central challenge in Brazil since the reinstate- ment of democracy in the mid-1980s. The evolving structure, role and effectiveness of the country’s judicial system have been major factors in that effort. -

Remarks at a Rally for Mayor David Dinkins in New York City October 28, 1993

Oct. 28 / Administration of William J. Clinton, 1993 make a contribution in accordance with our abil- time next year on the health care plan. It will ity to pay. begin with this, and the more people who know It goes way beyond that. We have certain what's in this, the more people who make con- group behaviors in this country that are impos- structive suggestions about how it can be im- ing intolerable burdens on the health care sys- proved, the better off we're all going to be. tem, which will never be remedies. And we So I ask you to think about this: This book must recognize every time another kid takes an- will be in every library in the country. It will other assault weapon onto another dark street be available, widely available. And now that the and commits another random drive-by shooting Government Printing Office has printed it, any and sends another child into the Johns Hopkins other publisher in the country can go out and emergency room, that adds to the cost of health try to print it for a lower cost. That's good. care. It is a human tragedy. It is also the dumb- That means we'll have a little competition and est thing we can permit to continue to go on these books will be everywhere. [Laughter] for our long-term economic health. Why do we I want to implore all of you to get this and continue to permit this to happen? read it, to get as many of your friends and And so we need to advocate those things, neighbors as possible to read it, and to create too. -

Journal of Law and Business

\\server05\productn\N\NYB\3-2\NYB201.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JUL-07 12:45 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF LAW AND BUSINESS VOL. 3 Spring 2007 No. 2 COURT OF LAW AND COURT OF PUBLIC OPINION: SYMBIOTIC REGULATION OF THE CORPORATE MANAGEMENT DUTY OF CARE TAMAR FRANKEL* INTRODUCTION The story of the Disney Corporation, Michael Eisner, and Michael Ovitz. On August 9, 2005, the Delaware Chancery Court handed down a decision that exonerated the defendant directors of Disney Company and its top management from liability for their handling of the Ovitz Affair.1 The story is quite simple. Disney’s president died in an accident, and the corporation’s CEO, Michael Eisner, underwent a heart opera- tion. Disney needed a successor president and immediate help for its ailing CEO. Eisner, who had been courting his friend, the famous Michael Ovitz, for years, approached him again. As this was an opportune time for Ovitz as well, the deal was struck, and Ovitz moved to Disney as its president. The new president did not work out. He did not merge into the Disney culture, had difficulties in being close to the very commanding and demanding Eisner, and to two top executives, who were resentful of Ovitz, and who continued to report to Eisner. Af- ter about one year, Ovitz’s contract with Disney was termi- nated. The termination, after a year of unsatisfactory service, * Professor of Law, Michaels Faculty Scholar, Boston University School of Law. 1. In re Walt Disney Co. Derivative Litig., 907 A.2d 693 (Del. Ch. 2005), aff’d sub nom., Brehm v. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1974-07-19

• Title 9 may change intramural programs base, cover, ByMAVREENCONNORS III Omaha earlier thll weell tIIat the of men and women's physical improve and expand their rlaucial aid II IIGII-diIcrimiutory lo-Technlca AT A.IOC. Newl Editor generaUty ,WII to aUow "nelibUlty" education would have to merge. capabilities. This same affirmative but lOme I.anll liven to Ute UI by Now 10 that rules could apply to the IIlIny At that regional briefing Gregory effort must be made in academic friends aad alumal of Ute olvenlty Second of two part story dlrrerent educational IIIIUlutions bI could not give specific answers in five areas. specify a Iblgle IU. the V.S. or six areas, including those men Disabilities related to pregnancy, '259 Tb ... the guldeUnes Ire not tioned above. She emphasized that the p childbirth, miscarriage, abortion or Under proposed Department of Questions arise whether the senior Lam S~hool proposed guidelines, two years in brollen down 10 the bltramural level, recovery from the above would be Health, Education and Welfare women's honor society, Mortar Gregory laid that a IltlUltiOO III wbicb I compilation and revision, barring sex treated as any other temporary (HEW) guidelinea, the intramural Board, could continue as a single sex 011 Over $1 million has been raised by the UI lAw discrimination are not "set In competition lan't required 10 get disability . program at the UI would probably organization. Also, the university i8 School fWld drive, according to Law School Dean cement." the team. co-eti teaml w... 1d be have to be entirely co-educational, planning only a women'8 non-eo-ed Quotas already gone from the UI LawmlCe Blades. -

For Disney's Eisner, Years of Corporate Sparring Catch Up

Article View Page 1 of 3 « Back to Article View Databases selected: Multiple databases... Fading Magic: For Disney's Eisner, Years Of Corporate Sparring Catch Up; Chief of Entertainment Giant Faces a Day of Reckoning; 'Too Little, Too Late'; In Talks on Giving Up a Title Bruce Orwall and Joann S. Lublin. Wall Street Journal. (Eastern edition). New York, N.Y.: Mar 1, 2004. pg. A.1 Author(s): Bruce Orwall and Joann S. Lublin Publication title: Wall Street Journal. (Eastern edition). New York, N.Y.: Mar 1, 2004. pg. A.1 Source Type: Newspaper ISSN/ISBN: 00999660 ProQuest document ID: 564435041 Text Word Count 1623 Article URL: http://gateway.proquest.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2003&res_ id=xri:pqd&rft_val_fmt=ori:fmt:kev:mtx:journal&genre=article &rft_id=xri:pqd:did=000000564435041&svc_dat=xri:pqil:fmt=tex t&req_dat=xri:pqil:pq_clntid=9269 Abstract (Article Summary) Disney's board has so far stood behind Mr. [Michael Eisner]. People familiar with the board's thinking say members want time to evaluate the results of the vote to decipher whether it represents frustration with Disney's governance, its overall performance or personal animosity toward Mr. Eisner. Even if a large number of Disney shareholders oppose Mr. Eisner's board re-election this week, it isn't likely that the board will make a move on Mr. Eisner immediately, at least in part because it doesn't want to signal instability in the face of the Comcast bid. The immediate source of Mr. Eisner's troubles was his and the board's decision in November to enforce a mandatory retirement policy that would force out Director Roy E.