List of New York's Baseball Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Senator Lehman As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu Will Deliver

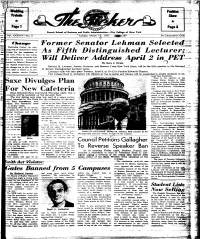

:iVn-1,,TSW«a^ .-•tfinrf.V. .,+,. •"- • , --v Show ' • • V '•<•'' •• — * Page 3 '•"•:• ^U- Baruch School of Business and Public Administration City College of New York Vol: XXXVri!—No. 8 Tuesday. March 19. 1957 389 By Subscription -Only Former Senator Lehman Beginning Friday, the cafe- [tgria will be clooed at 3 evei> Friday- for the remainder of As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu [the term. Prior to this ruling, the cafeteria was closed &t 4:30. [The Cafeteria Committee, Will Deliver Address April 2 in [headed by Ed-ward Mamraen of By Gary J. Strum . -i| the Speech Department, made O the change due to lack of busi Herbert H. Lehman, former Governor and Senator f rom New York State, will be the fifth speaker in the Bernard ness after 3. There is no eve- M. Baruch Distinguished Lecturer series. " * " I ning session service Fridays. Lehman's talk will take place Tuesday, April 2, at 10:15 in Pauline Edwards Theatre. .•...•---. " ; / City College Buell G. Gallagher will officiate at the occasion and classes will be suspended to enable students to'afc- : tend the function. Prior to his election to the United States Senate in 1949, axe Divulges Plan Lehman worked as Director Gen-, eral of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administra tion. or New Cafeteria Lehman was born in New York Dean Emanuel Saxe announced Thursday night that a City March 28, 1878, and he re afeteria will be installed on the eleventh floor. ceived a BA degree from Wil The new dining area plan was part of a space survey liams College. -

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

St John S Athletics Hall of Fa

St. John’s Athletics Hall of Fame Table of Contents Induction Classes ................................................................................................................... 4 Class of 1984-85 ............................................................................................................................. 4 Class of 1985-86 ............................................................................................................................. 5 Class of 1986-87 ............................................................................................................................. 6 Class of 1987-88 ............................................................................................................................. 7 Class of 1988-89 ............................................................................................................................. 8 Class of 1989-90 ............................................................................................................................. 9 Class of 1990-91 ........................................................................................................................... 10 Class of 1991-92 ........................................................................................................................... 11 Class of 1992-93 ........................................................................................................................... 12 Class of 1993-94 .......................................................................................................................... -

Nagurski's Debut and Rockne's Lesson

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 20, No. 3 (1998) NAGURSKI’S DEBUT AND ROCKNE’S LESSON Pro Football in 1930 By Bob Carroll For years it was said that George Halas and Dutch Sternaman, the Chicago Bears’ co-owners and co- coaches, always took opposite sides in every minor argument at league meetings but presented a united front whenever anything major was on the table. But, by 1929, their bickering had spread from league politics to how their own team was to be directed. The absence of a united front between its leaders split the team. The result was the worst year in the Bears’ short history -- 4-9-2, underscored by a humiliating 40-6 loss to the crosstown Cardinals. A change was necessary. Neither Halas nor Sternaman was willing to let the other take charge, and so, in the best tradition of Solomon, they resolved their differences by agreeing that neither would coach the team. In effect, they fired themselves, vowing to attend to their front office knitting. A few years later, Sternaman would sell his interest to Halas and leave pro football for good. Halas would go on and on. Halas and Sternaman chose Ralph Jones, the head man at Lake Forest (IL) Academy, as the Bears’ new coach. Jones had faith in the T-formation, the attack mode the Bears had used since they began as the Decatur Staleys. While other pro teams lined up in more modern formations like the single wing, double wing, or Notre Dame box, the Bears under Jones continued to use their basic T. -

CITY of HUBER HEIGHTS STATE of OHIO City Dog Park Committee Meeting Minutes March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M

Agenda Page 1 of 1 CITY OF HUBER HEIGHTS STATE OF OHIO City Dog Park Committee March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M. City Hall – 6131 Taylorsville Road – Council Chambers 1. Call Meeting To Order/Roll Call: 2. Approval of Minutes: A. March 22, 2018 3. Topics of Discussion: A. City Dog Park Planning and Discussion 4. Adjournment: https://destinyhosted.com/print_all.cfm?seq=3604&reloaded=true&id=48237 3/29/2018 CITY OF HUBER HEIGHTS STATE OF OHIO City Dog Park Committee Meeting Minutes March 29, 2018 6:00 P.M. City Hall – 6131 Taylorsville Road – City Council Chambers Meeting Started at 6:00pm 1. Call Meeting To Order/Roll Call: Members present: Bryan Detty, Keith Hensley, Vicki Dix, Nancy Byrge, Vincent King & Richard Shaw Members NOT present: Toni Webb • Nina Deam was resigned from the Committee 2. Approval of Minutes: No Minutes to Approval 3. Topics of Discussion: A. City Dog Park Planning and Discussion • Mr. King mentioned the “Meet Me at the Park” $20,000 Grant campaign. • Mr. Detty mentioned the Lowe’s communication. • Ms. Byrge discussed the March 29, 2018 email (Copy Enclosed) • Mr. Shaw discussed access to a Shared Drive for additional information. • Mr. King shared concerns regarding “Banning” smoking at the park as no park in Huber is currently banned. • Ms. Byrge suggested Benches inside and out of the park area. • Mr. Hensley and the committee discussed in length the optional sizes for the park. • Mr. Detty expressed interest in a limestone entrance area. • Mr. Hensley suggested the 100ft distance from the North line of the Neighbors and the School property line to the South. -

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects an Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State

Dodgers and Giants Move to the West: Causes and Effects An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) By Nick Tabacca Dr. Tony Edmonds Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2004 May 8, 2004 Abstract The history of baseball in the United States during the twentieth century in many ways mirrors the history of our nation in general. When the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants left New York for California in 1957, it had very interesting repercussions for New York. The vacancy left by these two storied baseball franchises only spurred on the reason why they left. Urban decay and an exodus of middle class baseball fans from the city, along with the increasing popularity of television, were the underlying causes of the Giants' and Dodgers' departure. In the end, especially in the case of Brooklyn, which was very attached to its team, these processes of urban decay and exodus were only sped up when professional baseball was no longer a uniting force in a very diverse area. New York's urban demographic could no longer support three baseball teams, and California was an excellent option for the Dodger and Giant owners. It offered large cities that were hungry for major league baseball, so hungry that they would meet the requirements that Giants' and Dodgers' owners Horace Stoneham and Walter O'Malley had asked for in New York. These included condemnation of land for new stadium sites and some city government subsidization for the Giants in actually building the stadium. Overall, this research shows the very real impact that sports has on its city and the impact a city has on its sports. -

National Football League Franchise Transactions

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 4 (1982) The following article was originally published in PFRA's 1982 Annual and has long been out of print. Because of numerous requests, we reprint it here. Some small changes in wording have been made to reflect new information discovered since this article's original publication. NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE FRANCHISE TRANSACTIONS By Joe Horrigan The following is a chronological presentation of the franchise transactions of the National Football League from 1920 until 1949. The study begins with the first league organizational meeting held on August 20, 1920 and ends at the January 21, 1949 league meeting. The purpose of the study is to present the date when each N.F.L. franchise was granted, the various transactions that took place during its membership years, and the date at which it was no longer considered a league member. The study is presented in a yearly format with three sections for each year. The sections are: the Franchise and Team lists section, the Transaction Date section, and the Transaction Notes section. The Franchise and Team lists section lists the franchises and teams that were at some point during that year operating as league members. A comparison of the two lists will show that not all N.F.L. franchises fielded N.F.L. teams at all times. The Transaction Dates section provides the appropriate date at which a franchise transaction took place. Only those transactions that can be date-verified will be listed in this section. An asterisk preceding a franchise name in the Franchise list refers the reader to the Transaction Dates section for the appropriate information. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Laobrabma Eggs

3, 1894. jlOHAYE, TY,MO. Cattle, bulls Rt low �&SON, I., Kansas. �1I1lNE 10. I ,ollng '1 ,OliO rOkCrI,UOO Ie In- �O:d �y-two I . \ due. at 10 ESTABLISHED 1888. l J SIXTEEN TO TWENTY VOL. XXXII, No. 41. f TOPEKA, KANSAS, WEDNESDAY, OCTOb�i� 10,1894. 1 PAGl!lS-.U.OO A YEAH. 110. I TABLE' OF CONTENTS. SWINE. SWINE. CATTLE. � TROTT. Abilene, Kae.":Pedtgreed POland-ChI CLOVER LA.WN HERD /D'• Il,I's and Duroo-Jerseys. Also M. B. Turkeys. POLAND-CHINAS. s� SLOPE FARM, PAGE 2-THB STOOX 1l'ITBBBBT.-A Valu Llgbt'Brabma. Plymonth Rook, S. Wyandotte ohlok Young BOWS' and boar81!oDd ens and R. Pekin du·oks. Of the C.,B. CROSS, Proprietor, Emp.orla, Kas • able Experiment. Our Ex Eggs. b.est. Cheap. •4. Hog-Feeding �!���!'�f:. Breeder of pure-bred Herefords. Beau Real 11006 Trade. Kaffir Fodder. Live f���I:H�::'� port Corn IMPROVED CHESTER SWINE-Pure·bred W.N.D. BIRD, EmpOria, Kae. heads the herd. Young bulls and heifers for sale. �lId- Stock Husbandry. OHIOand registered. Stock of all ages and botb sexes Also for Bale, Poland·Chlna swine. Choice bred I line PAGE S-AGBIOULTURAL MATTBRB.-Wheat for nle by H. S. Day. Dwight. MORI. Co., Kae. P. A. PEARSON f the and Wheaten Flour. Don't Sacrifice Your ��:�:r:t��J�f�!c'2���!!� V�:��reFa��J:�lzgi axes, W. the noted' Duohen and Lee strains of N. H. TJlEMANSON, wathena, DonIphan co., Kansal!, .. Lady An Alfalfa Balance-Sheet. Feed KInsley, (fOnS Hay. A• Kansae.- Large Poland-China pigs sired oy Breeder of Gentry. -

Easy to Get To. Hard to Leave

C M Y K P1 TRAVEL 06-01-08 EZ EE P1 CMYK [ABCDE] THE LONG P WEEKEND Yurts . in N.J. Page 8 Travel Sunday, June 1, 2008 R COMINGANDGOING » Securing an airfare refund. A pricing mystery . Checkout shocker . Page P2 Bugged by Bag Fee? It Could Be Worse. Peeved about shelling out 15 bucks to check a bag on American Airlines? We’re not A Fan Gets One Last Look happy about it, either, but here’s the good/bad news: It’s still the At NYC’s Storied Stadiums cheapest method of getting your bag from here to there. Here’s By Peter Mandel how $15 compares with the cost Special to The Washington Post of shipping one medium-size ver since the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants suitcase and its contents (total fought over it, New York has been the na- weight 35 pounds) one way from tion’s baseball town. Growing up there in downtown Washington to the 1960s and ’70s, I lived for summer downtown San Francisco. home-game nights: the Yanks’ Graig Nettles Elaunching a space shot of a homer, the Mets’ Tom Seav- — Elissa Leibowitz Poma er whiffing the side. We are the home of the Subway Series, manhole- POSTAL SERVICE cover bases for stickball, Mantle vs. Mays. We’ve got more pennants than you do. More than we can fly. K U.S. Postal Service Truth is, I live in New England now. But I can’t stop 800-275-8777 obsessing over my Mets via TV and beating my Big www.usps.com Apple baseball drum. -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig