The Racial Riots of the Red Summer of 1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alabama Municipal Journals December 2007 Volume 65, Number 6 Happys Holidays from the League Officers and Staff ! SS

SS SS S S 6 65, Number Volume S Alabama League of Municipalities Presorted Std. PO Box 1270 Alabama League of MunicipalitiesU.S. POSTAGE Montgomery,P.O. AL Box36102 1270 PAID December 2007 December Montgomery, AL 36102Montgomery, AL Happy Holidays from the League Officers and Staff ! Happy Holidays from the League Officers and Staff CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PERMIT NO. 340 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Journal The Alabama Municipal The S S Write or Call TODAY: Steve Martin Millennium Risk Managers Municipal Workers Compensation Fund, Inc. P.O. Box 26159 P.O. Box 1270 Birmingham, AL 35260 Montgomery, AL 36102 1-888-736-0210 334-262-2566 The Municipal Worker’s Compensation Fund has been serving Alabama’s municipalities since 1976. Just celebrating our 30th year, the MWCF is the 2nd oldest league insurance pool in the nation! • Discounts Available • Over 625 Municipal Entities • Accident Analysis Participating • Personalized Service • Loss Control Services Including: • Monthly Status Reports -Skid Car Training Courses • Directed by Veteran Municipal -Fire Arms Training System Offi cials from Alabama (FATS) ADD PEACE OF MIND Municipal Workers Compensation Fund Compensation Workers Municipal The Alabama Municipal Contents A Message from the Editor .................................4 Journal The Presidents’s Report .....................................5 Congress Passes, President Signs Temporary Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities Internet Tax Moratorium Extension December 2007• Volume 65, Number 6 Municipal Overview ..........................................7 -

Bloody Bogalusa and the Fight for a Bi-Racial Lumber Union: a Study

BLOODY BOGALUSA AND THE FIGHT FOR A BI-RACIAL LUMBER UNION: A STUDY IN THE BURKEAN REBIRTH CYCLE by JOSIE ALEXANDRA BURKS JASON EDWARD BLACK, COMMITTEE CHAIR W. SIM BUTLER DIANNE BRAGG A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Communication Studies in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Josie Alexandra Burks 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The Great Southern Lumber Mill (Great Southern Lumber), for which Bogalusa, Louisiana was founded in 1906, was the largest mill of its kind in the world in the early twentieth century (Norwood 591). The mill garnered unrivaled success and fame for the massive amounts of timber that was exported out of the Bogalusa facility. Great Southern Lumber, however, was also responsible for an infamous suppression of a proposed biracial union of mill workers. “Bloody Bogalusa” or “Bogalusa Burning,” to which the incident is often referred, occurred in 1919 when the mill’s police force fired on the black leader of a black unionist group and three white leaders who supported unionization, killing two of the white leaders, mortally wounding the third, and forcing the black unionist to flee from town in order to protect his life (Norwood 592). Through the use of newspaper articles and my personal, family narrative I argue that Great Southern Lumber Company, in order to squelch the efforts of the union leaders, engaged in a rhetorical strategy that might be best examined through Kenneth Burke’s theory of the Rebirth Cycle. -

The Evidence

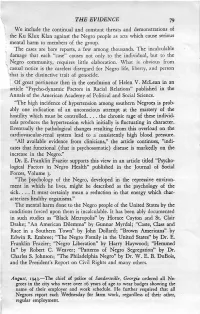

THE EVIDENCE 79 We include the continual and constant threats and demonstrations of the Ku Klux Klan against the Negro people as acts which cause serious mental harm to members of the group. The cases are bare reports, a few among thousands. The incalculable damage that each "case" causes not only to the individual, but to the Negro community, requires little elaboration. What is obvious from , casual notice is the careless disregard for Negro life, liberty, and person ' _hat is the distinctive trait of genocide. ~ Of great pertinence then in the conclusion of Helen V. McLean in an article "Psycho-dynamic Factors in Racial Relations" published in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. "The high incidence of hypertension among southern Negroes is prob ably one indication of an· unconscious attempt at the mastery of the hostility which must be controlled .... the chronic rage of these individ uals produces the hypertension which initially. is fluctuating in character . Eventually the pathological changes resulting from this overload on the cardiovascular-renal system lead to a consistently high blood pressure. "All available evidence from clinicians," the article continues, "indi cates that functional (that is psychosomatic) disease is markedly on the increase in the Negro." Dr. E. Franklin Frazier supports this view in an article titled "Psycho logical Factors in Negro Health" published in the Journal of Social Forces, Volume 3· "The psychology of the Negro, developed in the repressive environ ment in which he lives, might be described as the psychology of the sick .... It must certainly mean a reduction in that energy which char acterizes healthy organisms." The mental harm done to the Negro people of the United States by the conditions forced upon them is incalculable. -

Totalitarian Dynamics, Colonial History, and Modernity: the US South After the Civil War

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

November 2003 Journal

November 2003 Volume 61, Number 5 Happy Thanksgiving from the League Officers and Staff! CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Alabama League of Municipalities Montgomery Inside: PO Box 1270 , AL , AL 36102 • Final Report: 2003 2nd Special Session • What Every Candidate Should Know About Municipal Government PERMIT NO. 340 Montgomery U.S. POST Presorted Std. PAID • Proposed Policies and Goals for 2004 AGE , AL ADD PEACE OF MIND By joining our Municipal Workers Compensation Fund! • Discounts Available • Directed by Veteran Municipal Officials • Accident Analysis from Alabama • Personalized Service • Over 550 Municipal Entities Participating • Monthly Status Reports Write or Call TODAY: Steve Martin Millennium Risk Managers Municipal Workers P.O. Box 26159 Compensation Fund, Inc. Birmingham, AL 35260 P.O. Box 1270 1-888-736-0210 Montgomery, AL 36102 334-262-2566 Contents Perspectives ......................................................................................4 AMROA Installs New Officers Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities November 2003 • Volume 61, Number 5 President’s Report ....................................................................... 5 So You Think You’ve Heard It All • OFFICERS Municipal Overview ................................................................... 7 DAN WILLIAMS, Mayor, Athens, President JIM BYARD, JR., Mayor, Prattville, Vice President Final Report: 2003 2nd Special Session PERRY C. ROQUEMORE, JR., Montgomery, Executive Director • CHAIRS OF THE LEAGUE’S STANDING COMMITTEES Environmental Outlook -

Chicagská Škola – Interdisciplinární Dědictví Moderního Výzkumu Velkoměsta

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Katedra teorie kultury (kulturologie) Obecná teorie a dějiny umění a kultury Tobiáš Petruželka Chicagská škola – interdisciplinární dědictví moderního výzkumu velkoměsta Chicago School – The Interdisciplinary Heritage of the Modern Urban Research Disertační práce Vedoucí práce – PhDr. Miloslav Lapka, CSc. 2014 1 „Prohlašuji, že jsem disertační práci napsal samostatně s využitím pouze uvedených a řádně citovaných pramenů a literatury a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu.“ V Helsinkách 25. 3. 2014 Tobiáš Petruželka 2 Poděkování Poděkování patří především vedoucímu práce dr. Miloslavu Lapkovi, který, ač převzal vedení práce teprve před rokem a půl, se rychle seznámil s tématem i materiálem a poskytl autorovi práce potřebnou podporu. Poděkování patří i dr. Jitce Ortové, která se vedení této disertace i doktorského studia s péčí věnovala až do skončení svých akademických aktivit. Díky také všem, kteří text v různých fázích četli a komentovali. Helsinské univerzitní knihovně je třeba vyslovit dík za systematické a odborné akvizice a velkorysé výpůjční lhůty. Abstrak t Cílem disertace je interdisciplinární kontextualizace chicagské sociologické školy, zaměřuje se především na ty její aspekty, jež se týkají sociologických výzkumů města Chicaga v letech 1915–1940. Cílem práce je propojit historický kontext a lokální specifika tehdejších výzkumů s výzkumným programem chicagské školy a jeho naplňováním. Nejprve jsou přiblíženy vybrané výzkumy, které chicagskou školy předcházely, dále jsou představena konceptuální a teoretická východiska jejího výzkumného programu. Nakonec jsou v tématických kapitolách kriticky prozkoumány nejvýznamnější monografie chicagské školy z let 1915–1940. Disertace se zabývá především tématy moderní urbánní kultury, migrace, kriminality a vývojem sociálního výzkumu v městském prostředí. -

Race and Sex Discrimination in Jury Service, 1868-1979 Dissertation

Revising Constitutions: Race and Sex Discrimination in Jury Service, 1868-1979 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Meredith Clark-Wiltz Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Paula Baker, Advisor Susan M. Hartmann David Stebenne Copyright By Meredith Clark-Wiltz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the relationship between the Reconstruction-era civil rights revolution and the rights revolution of the 1960s and 1970s by tracing the history of sex and race discrimination in jury service policy and the social activism it prompted. It argues that the federal government created a bifurcated policy that simultaneously condemned race discrimination and condoned sex discrimination during Reconstruction, and that initial policy had a controlling effect on the development of twentieth-century jury service campaigns. While dividing civil rights activists‘ campaigns for defendants‘ and jury rights from white feminists‘ struggle for equal civic obligations, the policy also removed black women from the forefront of either campaign. Not until the 1960s did women of color emerge as central to both of these campaigns, focusing on equal civic membership and the achievement of equitable justice. Relying on activists‘ papers, organizational records, and court cases, this project merges the legal and political narrative with a history of social to reveal the complex and mutually shaping relationship between policy and social activism. This dissertation reveals the distinctive, yet interwoven paths of white women, black women, and black men toward a more complete attainment of citizenship rights and more equitable access to justice. -

Border Physician: the Life of Lawrence A. Nixon, 1883-1966 Will Guzmán University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 Border Physician: The Life Of Lawrence A. Nixon, 1883-1966 Will Guzmán University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Guzmán, Will, "Border Physician: The Life Of Lawrence A. Nixon, 1883-1966" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2495. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2495 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BORDER PHYSICIAN: THE LIFE OF LAWRENCE A. NIXON, 1883-1966 By Will Guzmán, B.S., M.S., Ph.D. Department of History APPROVED ____________________________________ Maceo C. Dailey, Ph.D., Chair ____________________________________ Charles H. Ambler, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Jeffrey P. Shepherd, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Gregory Rocha, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Amilcar Shabazz, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School UMI Number: XXXXXXX Copyright December 2010 by Guzmán, Will All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Lynched for Drinking from a White Man's Well

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse this site you are agreeing to our use of cookies.× (More Information) Back to article page Back to article page Lynched for Drinking from a White Man’s Well Thomas Laqueur This April, the Equal Justice Initiative, a non-profit law firm in Montgomery, Alabama, opened a new museum and a memorial in the city, with the intention, as the Montgomery Advertiser put it, of encouraging people to remember ‘the sordid history of slavery and lynching and try to reconcile the horrors of our past’. The Legacy Museum documents the history of slavery, while the National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates the black victims of lynching in the American South between 1877 and 1950. For almost two decades the EJI and its executive director, Bryan Stevenson, have been fighting against the racial inequities of the American criminal justice system, and their legal trench warfare has met with considerable success in the Supreme Court. This legal work continues. But in 2012 the organisation decided to devote resources to a new strategy, hoping to change the cultural narratives that sustain the injustices it had been fighting. In 2013 it published a report called Slavery in America: The Montgomery Slave Trade, followed two years later by the first of three reports under the title Lynching in America, which between them detailed eight hundred cases that had never been documented before. The United States sometimes seems to be committed to amnesia, to forgetting its great national sin of chattel slavery and the violence, repression, endless injustices and humiliations that have sustained racial hierarchies since emancipation. -

The Scene on 9Th Street Was Repeated Across North Carolina That

Persistence and Sacrifice: Durham County‟s African American Community & Durham‟s Jeanes Teachers Build Community and Schools, 1900-1930 By Joanne Abel Date:____________________________________________________ Approved:________________________________________________ Dr. William H. Chafe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Liberal Studies Program in the Graduate School of Duke University Table of Contents Introduction: 3-7 Chapter 1: 8-21: The Aycock Education Reforms Chapter 2: 22-36: Jeanes Teachers: Going About Doing Good Chapter 3: 37-71: Durham‟s First Jeanes Teachers Chapter 4: 72-110: Adding Life and Interest to School Conclusion: 111-124 Notes: 125 Bibliography: 126-128 Acknowledgements: 129-130 Appendix Appendix 1: 131-132: Governor Charles Aycock‟s memorial on the State Capital lawn & education panel Appendix 2: 133-137: Durham County African American Schools, 1902-1930 Appendix 3: 138-139: Map Locating the African American Schools of Durham County Appendix 4: 140: Picture of the old white East Durham Graded School Appendix 5: 141-145: Copy of Dr. Moore‟s “Negro Rural School Problem” and Dr. Moore‟s pledge card Appendix 6: 146-148: Copy of “To The Negroes of North Carolina” Appendix 7:149: Picture of Mrs. Virginia Estelle Randolph, the first Jeanes teacher Appendix 8: 150-151: Copy of letter from Mr. F. T. Husband to Mr. N. C. Newbold Appendix 9: 152-154: Final Report on Rural School Buildings Aided by Mr. Rosenwald Appendix 10: 155: Copy of letter from Mattie N. Day to William Wannamaker Appendix 11:156: Black School Patrons Named in the Durham County School Board Minutes 1900-1930 Appendix 12: 157: Picture of Mrs. -

Tulsa Race Massacre / Black Wall Street Massacre / Greenwood Massacre

Radiology Diversity, Equity Inclusion & Belonging Program Tulsa Race Riots / Tulsa Race Massacre / Black Wall Street Massacre / Greenwood Massacre No matter what you call it, it marks one of “the single worst incidents of racial violence in American history”. Who was Dick Rowland? At the age of 19, Dick Rowland, a black man, held a job shining shoes in a white-owned and white- patronized shine parlor on Main Street in downtown Tulsa. At the time, Tulsa was a segregated city where black people were not allowed to use toilet facilities used by white people. There was no separate facility for blacks at the shine parlor where Rowland worked, and he had to use a segregated "Colored" restroom on the top floor of the nearby Drexel Building on S. Main Street. On May 30, 1921, Rowland entered the Drexel Building elevator. The story from there is he tripped and, trying to save himself from falling, grabbed the first thing he could, which happened to be the arm of the elevator operator, a 17 year old white girl named Sarah Page. Startled, Page screamed, and a white clerk in a first-floor store called police to report seeing Rowland flee from the elevator. The white clerk reported the incident as an attempted assault. Rowland was arrested the next day, on May 31, 1921. Upon his ar- rest, Rowland was taken to the city jail, a broken down, bug-infested jail that was inadequate. Later that afternoon, an anonymous call to the city jail, threatened Rowland’s life. After review of the situation, it was suggested to take Rowland out of town for his safety, but the sheriff refused, feeling his prisoner was safer in a secured cell than on the open road. -

Fran & Rich Juro

Fran & Rich Juro Written and Composed by Jason Robert Brown Originally Produced for the New York stage by Arielle Tepper and Mary Bell Originally Produced by Northlight Theatre Chicago, IL Feb. 26–March 21, 2021 Directed by Susan Baer Collins Scenic & Lighting Designer Music Director Jim Othuse Jim Boggess Costume Designer Properties Master Lindsay Pape Darin Kuehler Sound Designers Scenic Artist Tim Burkhart & Janet Morr John Gibilisco Production Coordinator Choreographer Greg Scheer Michelle Garrity Technical Director Stage Manager Darrin Golden Steve Priesman Assistant Director / OCP Directing Fellow Dara Hogan Audio and/or visual recording of this production is strictly prohibited. Hawks Mainstage Series Sponsor: Director’s Notes Cast Bios | Musical Numbers | Orchestra Love? CAST Cathy ......................................................... Bailey Carlson Like most enduring works in the theatre, The Jamie .....................................................Thomas A.C. Gjere Last Five Years is a love story. This one captures insightful and poignant moments in a relationship through a series of wonderful songs by composer MUSICAL NUMBERS Jason Robert Brown. Though the story is simple, Brown’s concept requires that these songs not be presented in a familiar, chronological way. Jamie’s Still Hurting ............................................................Cathy songs go forward in time, from the beginning to Shiksa Goddess ........................................................ Jamie the end of their five years together, while Cathy’s