Mapping the Experiences of African American Soldiers After World War I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

World War I Veterans Buried in the Town of Gorham and the Village of Rushville

World War I Veterans Buried in the Town of Gorham and the Village of Rushville World War I veteran, Bert Crowe, and his daughter, Regina Crowe, at the American Legion/VFW post monument in Rushville Village Cemetery. Daily Messenger. Jun. 29, 1983. Compiled by Preston E. Pierce Ontario County Historian 2018 July 1, 2018 Page 1 Allen, Charles F. New Gorham Cemetery Town of Gorham Grid coordinates: References: Allen, Charles F. AGO Form 724-1 1/2. Charles F. Allen. New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919. Available on the Internet at Ancestry.com. Form indicates that Allen was born in Geneva and was a resident of Penn Yan when he was inducted. He did not serve overseas. “Charles Allen.” [Obituary] Shortsville Enterprise. Jan. 26, 1968. p. 4. Obituary says that he worked for the Lehigh Valley RR and lived on Littleville Rd. in Shortsville. He died at the VA hospital in Batavia. The obituary says he was a veteran of World War II (Clearly an error). He was also a member of Turner-Schrader Post American Legion. It said that burial would be in Gorham Cemetery. “Obituaries. Charles F. Allen.” Daily Messenger. Jan. 22, 1968. p. 3. Obituary says that Allen was a native of Geneva who lived on Littleville Rd. [Town of Manchester] and was a machinist for the Lehigh Valley RR for many years. It does not mention veteran status except to say that he was a life-long member of the Turner-Schrader Post, American Legion in Shortsville. July 1, 2018 Page 2 Allen, Lloyd New Gorham Cemetery Town of Gorham Grid coordinates: References: Allen, Lloyd F. -

Race and WWI

Introductions, headnotes, and back matter copyright © 2016 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Cover photograph: American soldiers in France, 1918. Courtesy of the National Archives. Woodrow Wilson: Copyright © 1983, 1989 by Princeton University Press. Vernon E. Kniptash: Copyright © 2009 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Mary Borden: Copyright © Patrick Aylmer 1929, 2008. Shirley Millard: Copyright © 1936 by Shirley Millard. Ernest Hemingway: Copyright © 1925, 1930 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, renewed 1953, 1958 by Ernest Hemingway. * * * The readings presented here are drawn from World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It. Published to mark the centenary of the Amer- ican entry into the conflict, World War I and America brings together 128 diverse texts—speeches, messages, letters, diaries, poems, songs, newspaper and magazine articles, excerpts from memoirs and journalistic narratives— written by scores of American participants and observers that illuminate and vivify events from the outbreak of war in 1914 through the Armistice, the Paris Peace Conference, and the League of Nations debate. The writers col- lected in the volume—soldiers, airmen, nurses, diplomats, statesmen, political activists, journalists—provide unique insight into how Americans perceived the war and how the conflict transformed American life. It is being published by The Library of America, a nonprofit institution dedicated to preserving America’s best and most significant writing in handsome, enduring volumes, featuring authoritative texts. You can learn more about World War I and America, and about The Library of America, at www.loa.org. For materials to support your use of this reader, and for multimedia content related to World War I, visit: www.WWIAmerica.org World War I and America is made possible by the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

The Alabama Municipal Journals December 2007 Volume 65, Number 6 Happys Holidays from the League Officers and Staff ! SS

SS SS S S 6 65, Number Volume S Alabama League of Municipalities Presorted Std. PO Box 1270 Alabama League of MunicipalitiesU.S. POSTAGE Montgomery,P.O. AL Box36102 1270 PAID December 2007 December Montgomery, AL 36102Montgomery, AL Happy Holidays from the League Officers and Staff ! Happy Holidays from the League Officers and Staff CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PERMIT NO. 340 CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Journal The Alabama Municipal The S S Write or Call TODAY: Steve Martin Millennium Risk Managers Municipal Workers Compensation Fund, Inc. P.O. Box 26159 P.O. Box 1270 Birmingham, AL 35260 Montgomery, AL 36102 1-888-736-0210 334-262-2566 The Municipal Worker’s Compensation Fund has been serving Alabama’s municipalities since 1976. Just celebrating our 30th year, the MWCF is the 2nd oldest league insurance pool in the nation! • Discounts Available • Over 625 Municipal Entities • Accident Analysis Participating • Personalized Service • Loss Control Services Including: • Monthly Status Reports -Skid Car Training Courses • Directed by Veteran Municipal -Fire Arms Training System Offi cials from Alabama (FATS) ADD PEACE OF MIND Municipal Workers Compensation Fund Compensation Workers Municipal The Alabama Municipal Contents A Message from the Editor .................................4 Journal The Presidents’s Report .....................................5 Congress Passes, President Signs Temporary Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities Internet Tax Moratorium Extension December 2007• Volume 65, Number 6 Municipal Overview ..........................................7 -

Mack Studies

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 472 SO 024 893 AUTHOR Botsch, Carol Sears; And Others TITLE African-Americans and the Palmetto State. INSTITUTION South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. PUB DATE 94 NOTE 246p. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Black Culture; *Black History; Blacks; *Mack Studies; Cultural Context; Ethnic Studies; Grade 8; Junior High Schools; Local History; Resource Materials; Social Environment' *Social History; Social Studies; State Curriculum Guides; State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS *African Americans; South Carolina ABSTRACT This book is part of a series of materials and aids for instruction in black history produced by the State Department of Education in compliance with the Education Improvement Act of 1984. It is designed for use by eighth grade teachers of South Carolina history as a supplement to aid in the instruction of cultural, political, and economic contributions of African-Americans to South Carolina History. Teachers and students studying the history of the state are provided information about a part of the citizenry that has been excluded historically. The book can also be used as a resource for Social Studies, English and Elementary Education. The volume's contents include:(1) "Passage";(2) "The Creation of Early South Carolina"; (3) "Resistance to Enslavement";(4) "Free African-Americans in Early South Carolina";(5) "Early African-American Arts";(6) "The Civil War";(7) "Reconstruction"; (8) "Life After Reconstruction";(9) "Religion"; (10) "Literature"; (11) "Music, Dance and the Performing Arts";(12) "Visual Arts and Crafts";(13) "Military Service";(14) "Civil Rights"; (15) "African-Americans and South Carolina Today"; and (16) "Conclusion: What is South Carolina?" Appendices contain lists of African-American state senators and congressmen. -

Bloody Bogalusa and the Fight for a Bi-Racial Lumber Union: a Study

BLOODY BOGALUSA AND THE FIGHT FOR A BI-RACIAL LUMBER UNION: A STUDY IN THE BURKEAN REBIRTH CYCLE by JOSIE ALEXANDRA BURKS JASON EDWARD BLACK, COMMITTEE CHAIR W. SIM BUTLER DIANNE BRAGG A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Communication Studies in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2016 Copyright Josie Alexandra Burks 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The Great Southern Lumber Mill (Great Southern Lumber), for which Bogalusa, Louisiana was founded in 1906, was the largest mill of its kind in the world in the early twentieth century (Norwood 591). The mill garnered unrivaled success and fame for the massive amounts of timber that was exported out of the Bogalusa facility. Great Southern Lumber, however, was also responsible for an infamous suppression of a proposed biracial union of mill workers. “Bloody Bogalusa” or “Bogalusa Burning,” to which the incident is often referred, occurred in 1919 when the mill’s police force fired on the black leader of a black unionist group and three white leaders who supported unionization, killing two of the white leaders, mortally wounding the third, and forcing the black unionist to flee from town in order to protect his life (Norwood 592). Through the use of newspaper articles and my personal, family narrative I argue that Great Southern Lumber Company, in order to squelch the efforts of the union leaders, engaged in a rhetorical strategy that might be best examined through Kenneth Burke’s theory of the Rebirth Cycle. -

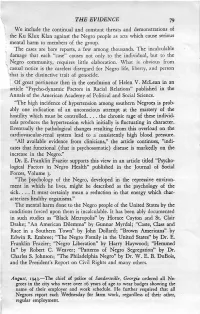

The Evidence

THE EVIDENCE 79 We include the continual and constant threats and demonstrations of the Ku Klux Klan against the Negro people as acts which cause serious mental harm to members of the group. The cases are bare reports, a few among thousands. The incalculable damage that each "case" causes not only to the individual, but to the Negro community, requires little elaboration. What is obvious from , casual notice is the careless disregard for Negro life, liberty, and person ' _hat is the distinctive trait of genocide. ~ Of great pertinence then in the conclusion of Helen V. McLean in an article "Psycho-dynamic Factors in Racial Relations" published in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. "The high incidence of hypertension among southern Negroes is prob ably one indication of an· unconscious attempt at the mastery of the hostility which must be controlled .... the chronic rage of these individ uals produces the hypertension which initially. is fluctuating in character . Eventually the pathological changes resulting from this overload on the cardiovascular-renal system lead to a consistently high blood pressure. "All available evidence from clinicians," the article continues, "indi cates that functional (that is psychosomatic) disease is markedly on the increase in the Negro." Dr. E. Franklin Frazier supports this view in an article titled "Psycho logical Factors in Negro Health" published in the Journal of Social Forces, Volume 3· "The psychology of the Negro, developed in the repressive environ ment in which he lives, might be described as the psychology of the sick .... It must certainly mean a reduction in that energy which char acterizes healthy organisms." The mental harm done to the Negro people of the United States by the conditions forced upon them is incalculable. -

1910-1919 Obituaries from the Catholic Tribune, St. Joseph, Missouri

1910-1919 Obituaries from The Catholic Tribune, St. Joseph, Missouri *indicates African-American [Included is an edition from 1920, but only noting 1919 deaths] Questions? Contact Monica [email protected] Name Age Death Date Edition Date Burial --, Abbonian [Br.] 81 26 Feb 1910 03-05-10 --, Castilda (or 10 May 1914 05-16-14 Cassilda) [Mother] --, John [Br.] 08 Nov 1910 11-12-10, 11-19-10 Mount Olivet --, Mary Frances 81 ?? Aug 1912 08-31-12 [Sr. --, Mary Salesia 25 Jul 1916 08-05-16 [Sr.] --, Prudentianna 22 Jan 1917 02-03-17 IL [Mother] --, Teresa [Sr.] 58 27 Aug 1910 09-03-01 Boston MA --, Vivian [Sister] 30 06 Dec 1918 12-14-18 St. Mary's Kansas City MO Adams, Frank 73 18 Sep 1917 09-22-17 Adley, John Joseph 68 18 Feb 1918 02-23-18 Mount Olivet Adley, Mary (Mrs.) 68 23 Jul 1917 07-28-17 Mount Olivet Akhurst, Robert H. 51 05 Jul 1910 07-09-10 Albin, Amanda 80 03 Aug 1919 08-09-19 Susan (Mrs.) Albus, Joseph 22 May 1910 05-28-10 Alders, Benjamin 23 23 Feb 1910 02-26-10 Mount Olivet E. Alexander, Conrad 40 23 Apr 1914 04-25-14 Mount Olivet Alexander, Frank S. 12 Jan 1912 01-20-12 Allee, Curtis 24 Nov 1919 11-29-19 Allee, James T. 24 Nov 1919 11-23-18, 11-29-19, 12-06-19 Allen, James H. 85 02 Nov 1917 11-17-17 NY Allen, Mary E. 20 05 Aug 1917 08-11-17 Allen, Samuel S. -

November 2003 Journal

November 2003 Volume 61, Number 5 Happy Thanksgiving from the League Officers and Staff! CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED Alabama League of Municipalities Montgomery Inside: PO Box 1270 , AL , AL 36102 • Final Report: 2003 2nd Special Session • What Every Candidate Should Know About Municipal Government PERMIT NO. 340 Montgomery U.S. POST Presorted Std. PAID • Proposed Policies and Goals for 2004 AGE , AL ADD PEACE OF MIND By joining our Municipal Workers Compensation Fund! • Discounts Available • Directed by Veteran Municipal Officials • Accident Analysis from Alabama • Personalized Service • Over 550 Municipal Entities Participating • Monthly Status Reports Write or Call TODAY: Steve Martin Millennium Risk Managers Municipal Workers P.O. Box 26159 Compensation Fund, Inc. Birmingham, AL 35260 P.O. Box 1270 1-888-736-0210 Montgomery, AL 36102 334-262-2566 Contents Perspectives ......................................................................................4 AMROA Installs New Officers Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities November 2003 • Volume 61, Number 5 President’s Report ....................................................................... 5 So You Think You’ve Heard It All • OFFICERS Municipal Overview ................................................................... 7 DAN WILLIAMS, Mayor, Athens, President JIM BYARD, JR., Mayor, Prattville, Vice President Final Report: 2003 2nd Special Session PERRY C. ROQUEMORE, JR., Montgomery, Executive Director • CHAIRS OF THE LEAGUE’S STANDING COMMITTEES Environmental Outlook -

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES in SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015

AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC PLACES IN SOUTH CAROLINA ////////////////////////////// September 2015 State Historic Preservation Office South Carolina Department of Archives and History should be encouraged. The National Register program his publication provides information on properties in South Carolina is administered by the State Historic in South Carolina that are listed in the National Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Register of Historic Places or have been Archives and History. recognized with South Carolina Historical Markers This publication includes summary information about T as of May 2015 and have important associations National Register properties in South Carolina that are with African American history. More information on these significantly associated with African American history. More and other properties is available at the South Carolina extensive information about many of these properties is Archives and History Center. Many other places in South available in the National Register files at the South Carolina Carolina are important to our African American history and Archives and History Center. Many of the National Register heritage and are eligible for listing in the National Register nominations are also available online, accessible through or recognition with the South Carolina Historical Marker the agency’s website. program. The State Historic Preservation Office at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History welcomes South Carolina Historical Marker Program (HM) questions regarding the listing or marking of other eligible South Carolina Historical Markers recognize and interpret sites. places important to an understanding of South Carolina’s past. The cast-aluminum markers can tell the stories of African Americans have made a vast contribution to buildings and structures that are still standing, or they can the history of South Carolina throughout its over-300-year- commemorate the sites of important historic events or history. -

Tee 1919 Race Riots in Britain: Ti-Lir Background and Conseolences

TEE 1919 RACE RIOTS IN BRITAIN: TI-LIR BACKGROUND AND CONSEOLENCES JACOLEUNE .ENKINSON FOR TI-E DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 1987 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis contains an empirically-based study of the race riots in Britain, which looks systematically at each of the nine major outbreaks around the country. It also looks at the background to the unrest in terms of the growing competition in the merchant shipping industry in the wake of the First World War, a trade in which most Black residents in this country were involved. One result of the social and economic dislocation following the Armistice was a general increase in the number of riots and disturbances in this country. This factor serves to put into perspective the anti-Black riots as an example of increased post-war tension, something which was occurring not only in this country, but worldwide, often involving recently demobilised men, both Black and white. In this context the links between the riots in Britain and racial unrest in the West Indies and the United States are discussed; as is the growth of 'popular racism' in this country and the position of the Black community in Britain pre- and post- riot. The methodological approach used is that of Marxist historians of the theory of riot, although this study in part, offers a revision of the established theory. ACKNOWLEDcEJvNTS I would like to thank Dr. Ian Duffield, my tutor and supervisor at Edinburgh University, whose guidance and enthusiasm helped me along the way to the completion of this thesis.