Faye Jessica Keegan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 28, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 October Booknews 2016 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Horrors! It’s already October…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. SATURDAY OCTOBER 1 2:00 PM Holmes x 2 WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 19 7:00 PM Laurie R King signs Mary Russell’s War (Poisoned Pen $15.99) Randy Wayne White signs Seduced (Putnam $27) Hannah Stories Smith #4 Laurie R King and Leslie S Klinger sign Echoes of Sherlock THURSDAY OCTOBER 20 7:00 PM Holmes (Pegasus $24.95) More stories, and by various authors David Rosenfelt signs The Twelve Dogs of Christmas (St SUNDAY OCTOBER 3 2:00 PM Martins $24.99) Andy Carpenter #14 Jodie Archer signs The Bestseller Code (St Martins $25.99) FRIDAY OCTOBER 21 7:00 PM MONDAY OCTOBER 3 7:00 PM SciFi-Fantasy Club discusses Django Wexler’s The Thousand Kevin Hearne signs The Purloined Poodle (Subterranean $20) Names ($7.99) TUESDAY OCTOBER 4 Ghosts! SATURDAY OCTOBER 22 10:30 AM Carolyn Hart signs Ghost Times Two (Berkley $26) Croak & Dagger Club discusses John Hart’s Iron House Donis Casey signs All Men Fear Me ($15.95) ($15.99) Hannah Dennison signs Deadly Desires at Honeychurch Hall SUNDAY OCTOBER 23 MiniHistoricon ($15.95) Tasha Alexander signs A Terrible Beauty (St Martins $25.99) SATURDAY OCTOBER 8 10:30 AM Lady Emily #11 Coffee and Club members share favorite Mary Stewart novels Sherry Thomas signs A Study in Scarlet Women (Berkley -

Extensions of R.Emarks

June 3, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 14601 for congressional redistricting, and for other of Michigan the Sleeping Bear Dunes Na By Mr. KING: purposes; to the Oommittee on the Judiciary. tional La.keshore, and for other purposes; to H.J. Res. 758. Joint resolution proposing By Mr. EDWARDS of Louisiana: the Committee on Interior and Insular an amendment to the Constitution of the H.R. 11818. A bill to amend the Internal Affairs. United States relating to the power of the Revenue· Code of 1954 to provide a basic H.R. 11830. A bill to assure the safe passage Supreme Court to declare any provision of $3,000 exemption from income tax for of all students enrolled in institutions of law constitutional; to the Committee on the amounts received as annuities, pensions, or higher learning, and for other purposes; to Judiciary. other retirement benefits; to the Committee the Committee on the Judiciary. H.J. Res. 759. Joint resolution proposing an on Ways and Means. By Mr. POLLOCK: amendment to the Constitution relating to By Mr. !CHORD (for himself and Mr. H.R. 11831. A bill to provide for an addi the appointment of members of the Supreme HUNGATE): tional staff employee for each Member of the Court of the United States; to the Commit H.R. 11819. A bill to provide for orderly House of Representatives representing a tee on the Judiciary. trade in footwear; to the Committee on Ways congressional district which is the only con By Mr. MINISH: and Means. gressional district authorized for an entire H.J. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington,D.C. National Library Service for the Blind andPhysically Handicapped. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0763-1 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 172p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Audiodisks; *Audiotape Recordings; Authors; *Blindness; *Braille;Government Libraries; Large Type Materials; NonprintMedia; *Novels; *Short Stories; *TalkingBooks IDENTIFIERS *Detective Stories; Library ofCongress; *Mysteries (Literature) ABSTRACT This document is a guide to selecteddetective and mystery stories produced after thepublication of the 1982 bibliography "Mysteries." All books listedare available on cassette or in braille in the network library collectionsprovided by the National Library Service for theBlind and Physically Handicapped of the Library of Congress. In additionto this largn-print edition, the bibliography is availableon disc and braille formats. This edition contains approximately 700 titles availableon cassette and in braille, while the disc edition listsonly cassettes, and the braille edition, only braille. Books availableon flexible disk are cited at the end of the annotation of thecassette version. The bibliography is divided into 2 Prol;fic Authorssection, for authors with more than six titles listed, and OtherAuthors section, a short stories section and a section for multiple authors. Each citation containsa short summary of the plot. An order formfor the cited -

Favourite Authors Enjoyed by Older Seniors

Favourite authors enjoyed by older seniors Session 405 “70 Plus: older seniors love the library too!”. OLA Super Conference 2013 “Nice” stories Lillian Beckwith Maeve Binchy James Herriot Grace Livingston Hill Gervase Phinn Rosamunde Pilcher Nicholas Sparks Patrick Taylor (Irish Country Doctor series) Westerns Louis L’Amour Donald Clayton Porter Dana Fuller Ross Frontier and pioneer fiction Pierre Berton Farley Mowat Laura Ingalls Wilder Mysteries Lillian Jackson Braun Agatha Christie Janet Evanovich Dick Francis Erle Stanley Gardner Sue Grafton J. J. Marric Ngaio Marsh Ed McBain James Patterson Ann Purser Wilbur Smith Alexander McCall Smith Rex Stout (Nero Wolfe series) Gentle romance Barbara Cartland Marion Chesney Catherine Cookson Clare Darcy (Regency romances) Gentle Romance continued… Georgette Heyer Mary Stewart Romance (may include some sexual content) Debbie Macomber Belva Plain Nora Roberts Danielle Steel Humour Stuart McLean P. G. Wodehouse Christian fiction Jan Karon Karen Kingsbury Janette Oke Historical fiction Pearl S. Buck (Good Earth trilogy) John Jakes (Civil war family sagas) Jean Plaidy (also wrote under Victoria Holt, Philippa Carr, Eleanor Burford, Elbur Ford, Kathleen Kellow, Anna Percival, Ellalice Tate) Edward Rutherford Elswyth Thane (American Revolution) Nigel Tranter (Scottish history) Non-fiction Bible Biographies (musicians, movie stars, royalty, war/political figures, explorers) Inspirational/uplifting (Chicken soup for the soul) Medical (macular degeneration) Reader’s Digest magazine Self-help (bereavement) For more information about CNIB Library: www.cniblibrary.ca CNIB Library Partners Program [email protected] 1-800-563-2642 ext. 7055 Follow @CNIBLibrary on Twitter. Like us on Facebook! . -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

A Cozy Mystery

A Cozy M ystery Juvenile Adult Continue • The Wedding Caper by Janice A. Thompson • Cody and the Mysteries of the Universe by Tricia • The Candy Cane Caper by Josi S. Kilpack Springstubb • Books Can be Deceiving by Jenn McKinlay • Skin & Bones by Franklin W. Dixon • Eggs in Purgatory by Laura Childs • The Case of the Vampire Cat by John R. Erickson • Chocolate Cream Pie Murder by Joanne Fluke • Super-Sized Slugger by Cal Ripken Jr. • Arkansas Traveler by Earlene Fowler • Snowbound Mystery by Gertrude Chandler Warner • Polar Star by Martin Cruz Smith • Mystery at Yellowstone National Park by Carole • The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie by Alan Marsh Bradley • Mystery of the Bad Luck Curse by Laura E. Williams • Diamond Rings are Deadly Things by Rachelle J. • Mystery of the Ivory Charm by Carolyn Keene Christensen • The Mystery by Garth Nix and Sean Williams • Hearts in Hiding by Betsy Brannon Green • Mystery of the Desert Giant by Franklin Dixon • The Forgotten by Heather Graham • The Mystery of Silas Finklebean by David Baldacci • Death of an Honest Man by M.C. Beaton • Cirak’s Daughter by Charlotte MacLeod • The Secret Adversary by Agatha Christie • Dying for Chocolate by Diane Mott Davidson Young Adult • Aunt Dimity’s Death by Nancy Atherton • The Cat Who Ate Danish Modern by Lilian Jackson • Always Emily by Michaela MacColl Braun • The Finisher by David Baldacci • The Hunt Ball by Rita Mae Brown • The Sacrifice by Diane Matcheck • Size 12 is Not Fat by Meg Cabot • Maid of Honor by Charlotte Macleod • Falling to Pieces by Vanetta Chapman • The Quilter’s Apprentice by Jennifer Chaiverini • Decked by Carol Higgins Clark • The No. -

Little Free Library Inventory

Little Free Library TUCSON inventory Broadmoor Broadway Village E ARROYO CHICO AND MALVERN STREET Jazz Up Your Junk by Linda Baker Why? by Catherine Ripley Scrabble Take me. by J. Kenner Cold Dassy Tree by Olive Ann Burns he Jester by James Patterson and Andrew Gross he Afair by Lee Child Walk Do Not Run to the Doctor by J.L. Rodale Dead Rechoning by Charlaine Harris Head First the Biology of Hope by Norman Cousins Duane’s Depressed by Larry McMurtry he Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie Boundaries in Dating by Dr. Henry Cloud Wreckers Gate by Eric T Knight Brunelleschi’s Dome by Ross King A Bend in the River by VS Naipaul Pygmy by Chuck Palahniuk In the Name of Honor by Richard North Patterson he English Patient by Michael Ondaatje Imaginairy Homelands by Salman Rushdie Deja Dead by Kathy Richs Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt he Best Loved Poems of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Selected by Caroline Kennedy he Girl wit the Dragon Tatoo by Stieg Larsson he May Bride by Suzannah Dunn he Waterwirks by E.L. Doctorow Waiting by Ha Jin he Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne Vanishing Acts by Jodi Picoult Tick Tock by James Patterson he Hardy Boys: he Shore Road Mystery he Lost Deep houghts by Jack Handey Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson Straight Talk for Teenage Girls by Annette Fuson Life is Just a Chair of Bowlies by Mary Engelbreit St. Dale by Sharyn McCrumb Islands, the Universe, Home by Gretel Ehrlich he Far Side of the World his is Where We Live by Janelle Brown Hotel by Arthur Hailey he Chocolate Book Bandit: A Chocolate Mystery -

Command & Commanders in Modern Warfare

COMMAND AND COMMANDERS , \ .“‘,“3,w) .br .br “Z ,+( ’> , . I ..M IN MODERN WARFARE The Proceedings of the Second Military History Symposium U.S. Air Force Academy 23 May 1968 Edited by William Geffen, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy O5ce of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy 1971 2nd edilion, enlarged let edition, United States Air Force Academy, 1969 Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, US. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number 0874-0003 ii PREFACE The essays and commentaries which comprise this book re- sulted from the Second Annual Military History Symposium, held at the Air Force Academy on 2-3 May 1968. The Military History Symposium is an annual event sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy. The theme of the first symposium, held on 4-5May 1967 at the Air Force Academy, was “Current Concepts in Military History.” Several factors inspired the inauguration of the symposium series, the foremost being the expanding interest in the field of military history demonstrated at recent meetings of the American Historical Association and similar professional organizations. A professional meeting devoted solely to the subject of military his- tory seemed appropriate. The Air Force Academy’s Department of History has been particularly concerned with the history of military affairs and warfare since the founding of the institution. -

Toponymy in the Arthurian Novels by Mary Stewart

TOPONYMY IN THE ARTHURIAN NOVELS BY MARY STEWART ТОПОНИМИКА АРТУРОВСКИХ РОМАНОВ МЭРИ СТЮАРТ MARY STEWART’IN ARTHUR KONULU ROMANLARINDA YER ADLARI * Andrey ANISIMOV ABSTRACT The article discusses toponymy in the Arthurian novels by the English writer Mary Stewart. The author of the article proves that native Celtic and Latinized Celtic toponyms are used in the novels along with modern English geographical names. The toponyms are considered from historical, geographical and linguistic points of view. Keywords: Mary Stewart, Arthurian Novels, Arthurian Legend, Toponymy, Place Name. АННОТАЦИЯ В данной статье рассматривается использование топонимов в артуровских романах английской писательницы Мэри Стюарт. Автор статьи доказывает, что в романах наряду с современными географическими названиями встречаются исконно кельтские и латинизированные кельтские топонимы. Топонимы рассматриваются с исторической, географической и лингвистической точек зрения. Ключевые Слова: Мэри Стюарт, Артуровские Романы, Артуровская Легенда, Топонимика, Географическое Название. ÖZET Makalede İngiliz yazarı olan Mary Stewart’ın artur romanlarında kullanılan toponimler tetkik edilmiştir. Yazar söz konusu romanlarda diğer çağdaş coğrafı adları ile birlikte öz Kelt’çe olan ve Latince’ye dönüştürülen Kelt’çe toponimlerin kullanıldığını ispat etmektedir. Toponimler tarihsel, coğrafyasal ve dilsel açısından incelenmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Mary Stewart, Arthur Romanları, Arthur Efsanesi, Yer Adları, Coğrafi Adları. * PhD, Associate Professor NEFU Mary Stewart (born 17 September 1916) is a popular English novelist, best known for her Arthurian novels, which straddles the boundary between the historical novel and the fantasy genre. All the five novels (“The Crystal Cave”, “The Hollow Hills”, "The Last Enchantment”, “The Wicked Day” and “The Prince and the Pilgrim”) are united by a common aim and portray Dark Age Britain (V-VI c.). -

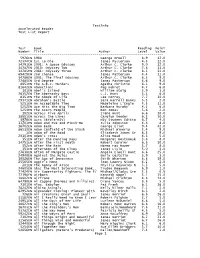

Testinfo Accelerated Reader Test List Report

TestInfo Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 9.0 12.0 34787EN 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13.0 34785EN 2061: Odyssey Three Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 11.0 69429EN 2nd Chance James Patterson 4.4 11.0 34786EN 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9.0 77485EN 3rd Degree James Patterson 4.6 9.0 8851EN The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9.0 81642EN Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6.0 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 76357EN The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6.0 8151EN The Abode of Life Lee Correy 7.7 10.0 29341EN Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks 5.3 2.0 5251EN An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11.0 5252EN Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6.0 5253EN The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 18801EN Across the Lines Carolyn Reeder 6.3 10.0 3976EN Acts (Bible-NIV) NIV Student Editio 6.7 4.0 11701EN Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me Julie Johnston 4.8 8.0 16702EN Adam Bede George Eliot 9.4 42.0 86533EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Michael Winerip 5.4 9.0 1EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 6.5 9.0 20101EN Adem's Cross Alice Mead 4.3 5.0 351EN After the Dancing Days Margaret Rostkowsk 3.8 8.0 14751EN After the First Death Robert Cormier 6.8 10.0 352EN After the Rain Norma Fox Mazer 3.7 8.0 353EN Afternoon of the Elves Janet Lisle 5.0 4.0 27638EN Afton of Margate Castle Angela Elwell Hunt 6.6 25.0 24940EN Against the Rules Emily Costello 3.9 3.0 10826EN The Age of Innocence Edith Wharton 8.8 19.0 25565EN Aggie's Home Joan Lowery Nixon 4.2 2.0 201EN The Agony of Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 5.3 5.0 74605EN Aha! The Most Interesting Book. -

Creating a Popular Romance Collection in an Academic Library

Creating a Popular Romance Collection in an Academic Library Sarah E. Sheehan and Jen Stevens Published online: August 2015 http://www.jprstudies.org Abstract: Over the past few decades, there has been a growing critical mass of scholarly interest in the study of popular romance fiction as a literary form in its own right. While much of the scholarship is available in academic libraries, few of the actual romance novels are. In response to curricular and faculty demand, two librarians decided to start a collection of popular romance novels at their academic library. This article discusses their rationale, methods, and process in creating the collection. Future directions and recommendations for other libraries are also given. About the Author: Sarah Sheehan is currently the liaison librarian for the College of Health & Human Services at George Mason University. Sarah received her MLS from Catholic University of America, a Master’s of Education in Instructional Design from George Mason University, and she is a Senior Member of the Academy of Health Information Professionals. She's the co-author, with George Mason Nursing faculty, of several articles and book chapters and wrote the book Romance Authors: A Research Guide, published in 2010 by Libraries Unlimited. Jen Stevens is the Humanities Liaison Librarian at George Mason University where she works with the English and Communication Departments, as well as the Women and Gender Studies Program. She holds an MA in English from the University of Colorado and an MLIS from the University of Texas. Jen has published articles on literary studies that range from J.R.R.