Overview of the Public Health Nutrition Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE, UPDATED 2010 American College of Physicians A Position Paper 2010 Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care A Summary of a Position Paper Approved by the ACP Board of Regents, April 2010 What Are the Sources of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care? The Institute of Medicine defines disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive poorer quality care compared with nonminorities, even when access-related factors, such as insurance status and income, are controlled. The sources of racial and ethnic health care disparities include differences in geography, lack of access to adequate health coverage, communication difficulties between patient and provider, cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and lack of access to providers. In addition, disparities in the health care system contribute to the overall disparities in health status that affect racial and ethnic minorities. Why is it Important to Correct These Disparities? The problem of racial and ethnic health care disparities is highlighted in various statistics: • Minorities have less access to health care than whites. The level of uninsurance for Hispanics is 34% compared with 13% among whites. • Native Americans and Native Alaskans more often lack prenatal care in the first trimester. • Nationally, minority women are more likely to avoid a doctor’s visit due to cost. • Racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia are 30% less likely than whites to use antidementia medications. -

Nutrition — Ph.D. 1

Nutrition — Ph.D. 1 NUTRITION — PH.D. Prerequisites • Master's degree in nutrition preferred; or an M.S. or M.P.H. degree Program director with completion of all prerequisite courses; or a health professional Sujatha Rajaram degree at the master's level or higher (M.D. or equivalent) • Advanced biochemistry (may be taken concurrently with the program) The Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree in nutrition prepares students to • Anatomy and physiology, microbiology, general chemistry, and effectively conduct nutrition research as well as apply nutritional science organic chemistry knowledge and appropriate research methods to address public health problems. The program provide's an advanced curriculum in nutrition, • G.P.A. of 3.5 or higher preferred th professional skills, and competencies required to support careers in • GRE or equivalent (above the 40 percentile in each section is teaching and research. This program is uniquely situated in the School favorable) of Public Health at a health sciences university. The program engages in interdisciplinary research, encouraging collaboration across public Individuals who may benefit from the health disciplines and the basic sciences, promoting and building upon its core legacy of vegetarian and plant-based nutrition. Areas of curricular program strength and research emphasis include plant-based diets and the health Individuals seeking careers in: of the individual, populations and the planet, nutritional epidemiology, diet • Academia (teaching and research) and chronic disease-risk reduction, and community nutrition. • Researcher in private industry, governmental agencies, nonprofit Students enrolled in this program are able to concurrently complete organizations, or research institutes coursework and practice experience necessary to sit for the registered • Public health nutritionist dietitian nutritionist (RDN) exam if not already an RDN. -

J. Michael Mcginnis, Md, Ma, Mpp

J. MICHAEL MCGINNIS, MD, MA, MPP National Academy of Medicine, the National Academies, 500 Fifth Street NW, Washington DC 20001, (202) 334-3963, [email protected] Highlights: Michael McGinnis is a physician and epidemiologist who lives and works in Washington DC. Through his writing, government service, and work in philanthropy, he has been a long-time contributor to national and international field leadership in health, health care, and health policy. He currently serves at the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), where he is the Leonard D. Schaeffer Executive Officer, Senior Scholar, and Executive Director of the NAM’s Leadership Consortium for public and private collaboration on behalf of a continuously learning health system. Previously, he served as founding Director, respectively, of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) Health Group, the World Health Organization’s Office for Health Reconstruction in Bosnia, the federal Office of Research Integrity (interim), and the federal Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. In a tenure unusual for political and policy posts, he held continuous appointment through the Carter, Reagan, Bush and Clinton Administrations at the Department of Health and Human Services, with policy responsibilities for disease prevention and health promotion (1977-1995). Programs and policies conceived and launched at his initiative include the Healthy People process establishing national health goals and objectives (1979-present), the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (1984-present), the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (with USDA, 1980- present), the multi-level Public Health Functions Steering Group and the Ten Essential Services of Public Health (1994-present), the RWJF Active Living family of programs (2000-present), the RWJF Young Epidemiology Scholars Program (2001-2012), the RWJF Health and Society Scholars Program (2002-2017), and the current Learning Health System initiative of the NAM. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

What the Public Thinks About Menatl Health and Mental Illness

What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and ~entaleI1lness A paper presented by Shirley A. Star, Senior Study Director National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago to the Annual Meeting The National Association for Mental Health, Inc. November 19, 1952 For the past two and a half years, the National Opinion Research Center has been engaged upon a pioneering study of the-American public's thinking in the field of mental health, under the joint sponsorship of the National Association for Mental Health and the National Institute of Mental Health, It is a vast and ambitious project, and I'm afraid that the title which has been assigned to my remarks about .the study is going to prove to be misleading in at least two ways. In the first place, and this must be obvious, both the title given me and the scope of the study cover Ear more ground than I could possibly present in the course of one afternoon. About all I can do today is hit a few of the high spots in public thinking and emphasize beforehand that the study aims to be inclusive. You can pretty well assume that it contains some information on just about any question in the area you might raise, even though I don't refer to many of them. So, as they say in the more enterprising shops--"If you don't see what you want, ask for it," In the second place, and this is more serious, I am in the em- barrassing position of having to stand here this afternoon and honestly- -2- admit that I don1t -know what the public thinks as yet. -

The Healthy Core Metabolism: a New Paradigm for Primary Preventive Nutrition Anthony Fardet, Edmond Rock

The Healthy Core Metabolism: A New Paradigm for Primary Preventive Nutrition Anthony Fardet, Edmond Rock To cite this version: Anthony Fardet, Edmond Rock. The Healthy Core Metabolism: A New Paradigm for Primary Pre- ventive Nutrition. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, Springer Verlag (Germany), 2016, 20 (3), pp.239-247. 10.1007/s12603-015-0560-6. hal-01458429 HAL Id: hal-01458429 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01458429 Submitted on 6 Feb 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. J Nutr Health Aging Volume 20, Number 3, 2016 THE HEALTHY CORE METABOLISM: A NEW PARADIGM FOR PRIMARY PREVENTIVE NUTRITION A. FARDET, E. ROCK 1INRA, Human Nutrition Department, JRU 1019, UNH, CRNH Auvergne, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand & Clermont Université, Université d’Auvergne, Unité de Nutrition Humaine, BP 10448, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France. Corresponding author: Dr. Edmond Rock, INRA, Human Nutrition Department, JRU 1019, UNH, CRNH Auvergne, F-63000 Clermont- Ferrand & Clermont Université, Université d’Auvergne, Unité de Nutrition Humaine, BP 10448, F-63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France, +33 (0)4 73 62 41 69, fax +33 (0)4 73 62 46 38, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Research in preventive nutrition aims at elucidating mechanism by which our diet helps us to remain in good health through optimal physiological functions. -

Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 Credit Hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas

University of Florida College of Public Health & Health Professions Syllabus PHC 6521: Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 credit hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas Instructor Name: Dr. von Castel Room Number: FSHN 227 Phone Number: 352 Email Address: [email protected] *****PLEASE USE THIS NOT CANVAS Office Hours: by appointment via phone,conferences (in canvas) or Lync(Microsoft) Preferred Course Communications: email through ufl.edu Prerequisites None PURPOSE AND OUTCOME Public health nutrition involves the promotion of health through nutrition and the prevention of nutrition related disease in a population. It focuses on improving the food choices, dietary intake, and nutritional status at the community, regional, or national level. The public health nutrition professional works to assess nutritional problems and needs by considering environmental causes, identifying intervention points, developing policies and programs to intervene at those points, implementing the policies or programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Course Overview This course will provide an introduction to Public Health Nutrition and the role of the Public Health Nutrition professional. Emphasis will be on definition, identification and prevention of nutrition related disease, as well as improving health of a population by improving nutrition. Malnutrition will be discussed on a societal, economic, and environmental level. It will include the basics of nutritional biochemistry as it relates to malnutrition of a community and targeted intervention. Finally, it will review existing programs and policies, including strengths, weaknesses and areas for modification or new interventions. Relation to Program Outcomes MPH Competencies covered 1. Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems 2. -

Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy 2

Getty Images / Maskot Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy January 2021 Historic and modern-day policies rooted in discrimination and oppression have created and widened harmful inequities impacting many communities of color. Effectively and equitably addressing mental health requires intervening at systemic and policy levels to dismantle the structures that produce negative outcomes like generational poverty, intergenerational and cultural trauma, racism, sexism, and ableism. Changing social, economic, and physical environments alongside key mental and behavioral health supports through immediate relief and longer-term fixes impact individual and community mental health and wellbeing. An individual’s mental health is impacted by and informs nearly every aspect of their life, identity, and community. CLASP looks at how one’s social, economic, and physical environment impact individual and community views of mental health and wellbeing. To improve mental health outcomes, we must think about an individual and family’s economic security, family support, and their community’s built environment. CLASP recognizes the influence of intergenerational and cultural trauma on communities and believes that all mental and behavioral health practices should be trauma-informed and healing- centered. Policymakers must significantly reform and reimagine systems that support the wellbeing of people with low incomes. This includes, but is not exclusive to: • Universal health coverage, as noted in our health care principles; • Recognizing -

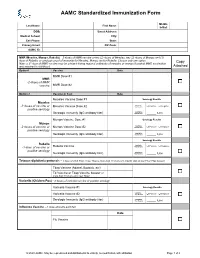

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (2015) Ministry of Health

Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (2015) Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Health Service Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, JAPAN 1-2-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan 100-8916 March 2018 This translation work was realized with the great help of Dr. Satoshi SASAKI (Toyko University) and Dr. Aki SAITO (National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition). Contents I Development and Application of Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 1 1 Introduction 2 2 Basics of Development 6 3 Considerations for Development 13 4 Application of the Dietary Reference Intakes 19 II Energy and Nutrients 32 Energy 33 Protein 66 Dietary Fat 81 Carbohydrate 104 Energy Providing Nutrients’ Balance 115 Vitamins (1) Fat-soluble Vitamins (2) Water-soluble Vitamins Vitamin A 126 Vitamin B1 154 Vitamin D 131 Vitamin B2 157 Vitamin E 137 Niacin 160 Vitamin K 140 Vitamin B6 163 Vitamin B12 167 Folate 170 Pantothenic acid 174 Biotin 177 Vitamin C 180 Minerals (1) Macrominerals (2) Microminerals Sodium 201 Iron 236 Potassium 206 Zinc 246 Calcium 210 Copper 249 Magnesium 216 Manganese 251 Phosphorus 218 Iodine 253 Selenium 257 Chromium 260 Molybdenum 262 I Development and Application I Development and Application of Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 1 I Development and Application 1.Introduction The Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese proposes reference values for the intake of energy and nutrients, in the Japanese population, comprising both healthy individuals and groups, for the promotion and maintenance of health, and to prevent the occurrence of lifestyle- related diseases (LRDs). The objectives behind the development of the Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (2015) are shown in Figure 1. -

COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for Health Care Providers, Workers and Settings

Updated September 2021 DOH 505-160 COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for health care providers, workers and settings Link to proclamation: 21-14.1 - COVID-19 Vax Washington General Proclamation Questions What does Proclamation 21-14.1 do? Proclamation 21-14.1, issued by Governor Inslee on August 20, 2021, made numerous changes to Proclamation 21-14, issued by Governor Inslee on August 9, 2021, but left the same core requirements in place. As before, the proclamation requires health care providers, defined broadly to include not only licensed health care providers but also all employees, contractors, and volunteers who work in a health care setting, to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 by October 18, 2021. It also requires operators of health care settings to verify the vaccination status of: a) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who works in the health care setting, whether or not they are licensed or providing health care services, and b) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who provides health care services for the health care setting operator. On what legal grounds can this be imposed? In response to the emerging COVID-19 threat, Governor Inslee declared a state of emergency on February 29, 2020, using his broad emergency authority under chapter 43.06 RCW. More specifically, under RCW 43.06.220, after a state of emergency has been declared, the governor may prohibit any activity that they believe should be prohibited to help preserve and maintain life, health, property or the public peace. Under an emergency such as this, the governor’s paramount duty is to protect the health and safety of our communities. -

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1 NOTES: Children in a prekindergarten setting should be age-appropriately immunized. The number of doses depends on the schedule recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Intervals between doses of vaccine should be in accordance with the ACIP-recommended immunization schedule for persons 0 through 18 years of age. Doses received before the minimum age or intervals are not valid and do not count toward the number of doses listed below. See footnotes for specific information foreach vaccine. Children who are enrolling in grade-less classes should meet the immunization requirements of the grades for which they are age equivalent. Dose requirements MUST be read with the footnotes of this schedule Prekindergarten Kindergarten and Grades Grades Grade Vaccines (Day Care, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 12 Head Start, and 11 Nursery or Pre-k) Diphtheria and Tetanus 5 doses toxoid-containing vaccine or 4 doses and Pertussis vaccine 4 doses if the 4th dose was received 3 doses (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/Td)2 at 4 years or older or 3 doses if 7 years or older and the series was started at 1 year or older Tetanus and Diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine Not applicable 1 dose and Pertussis vaccine adolescent booster (Tdap)3 Polio vaccine (IPV/OPV)4 4 doses 3 doses or 3 doses if the 3rd dose was received at 4 years or older Measles, Mumps and 1 dose 2 doses Rubella vaccine (MMR)5 Hepatitis B vaccine6 3 doses 3 doses or 2 doses of adult hepatitis B vaccine (Recombivax) for children who received the doses at least 4 months apart between the ages of 11 through 15 years Varicella (Chickenpox) 1 dose 2 doses vaccine7 Meningococcal conjugate Grades 2 doses vaccine (MenACWY)8 7, 8, 9, 10 or 1 dose Not applicable and 11: if the dose 1 dose was received at 16 years or older Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine 1 to 4 doses Not applicable (Hib)9 Pneumococcal Conjugate 1 to 4 doses Not applicable vaccine (PCV)10 Department of Health 1.