Sculpture in Site: Examining the Relationship Between Sculpture and Site in the Principal Works of Giambologna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sala Di Michelangelo E Della Scultura Del Cinquecento 2

MUSEO NAZIONALE DEL BARGELLO a sala, con volte a crociera ribassate, sostenute da robusti pilastri in pie- tra forte, fa parte del nucleo più antico del palazzo e la sua edificazione PIANO TERRA L 2 risale a poco dopo la metà del XIII secolo (1255-1260). Era in origine la sala d’ingresso e presumibilmente vi avevano sede i soldati e la “corte” (araldi, trombettieri, cavalieri) al servizio del podestà. Ospitava anche una cappella, Sala di Michelangelo dalla quale proviene la Madonna col Bambino (1), parte di un più vasto affresco di scuola giottesca che includeva i donatori, vari santi e fanciulli con i simboli dei sestieri della città, trasferito nell’Ottocento sulla parete della sala dove oggi si trova. Con la trasformazione del palazzo in carcere (dal 1574 al e della scultura 1857), il vasto ambiente fu suddiviso in più vani, destinati alle guardie e alle varie magistrature di giustizia. I volumi originari furono recuperati nel corso del restauro ottocentesco (1858-1865), demolendo le infrastrutture, e le pareti del Cinquecento furono dipinte da Gaetano Bianchi con decorazioni araldiche in stile gotico, secondo il gusto del tempo, successivamente imbiancate. Dall’istituzione del museo, nel 1865, all’alluvione del 1966, la sala accolse – assieme alla contigua sala della torre, oggi adibita a ingresso e biglietteria – la collezione dell’Armeria medicea. Nel riordinamento seguito all’alluvione, fu deciso di trasferire l’Armeria al secondo piano e di collocare qui le opere di Michelan- gelo e degli scultori del Cinquecento, precedentemente distribuite in ambienti diversi, secondo l’allestimento attuale, concepito da Luciano Berti e realizzato dall’architetto Carlo Cresti tra il 1970 e il 1975, oggi in parte modificato. -

Silke Kurth, Wasser, Stein Und Automaten. Die Grotten Von

The essay considers the grottoes of the Silke Kurth, Wasser, Stein und Automaten. Die Grotten von Pratolino oder Medici-Villa at Pratolino in regard to der Fürst als Demiurg their historic relevance in the context of the artistic and typological development Qui l’Arte, e la Natura as well as their function related to the Insieme a gara ogni sua grazia porge E fra quelle si scorge strategies of princely self-representation. La grandezza del animo, e la cura Thereby it will focus less on the moments Che le nutrisce, e cura of mere imitation of the nature than E fa splender più chiaro ogn’hor d’intorno rather on the imitation of the natural Di nuove meraviglie il bel soggiorno. creating act itself. The innovative type Gualterotti, 15791 of the grotto as basement for the grand villa merges the demand of the exclusive Der von Francesco I. de’Medici initiierte und durch Bernardo Buontalenti Gesamtkunstwerk with contemporary in den Jahren 1569–1585 realisierte Villen- und Parkkomplex von Pratolino, scientific, mechanical and geological- der heute leider nur noch spärliche Reste seiner früheren Gestaltung auf- cosmological ideas in a new and unique weist, wurde schon zur Bauzeit aufgrund seiner monumentalen künstlichen space of world knowledge. This feature Grotten Legende und erhielt umgehend Vorbildcharakter für die gesamte as a site of technical experiment and europäische Garten- und Grottenarchitektur.2 Mit dem im Italien des Cin- junction of various scientific disciplines, quecento entstehenden und nicht zuletzt auf spektakuläre zeitgenössische that stylises the ruler as a godlike crea- tor, will be considered in view of further archäologische Funde reagierenden Bautypus der künstlichen Grotte lebt coeval spaces of knowledge. -

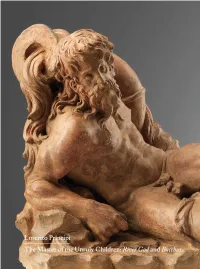

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Alla Villa Di Pratolino E Nei Giardini Del Castello Dei Gondi a Noisy-Le-Roi

Marco Calafati “Acconciar grotti” alla villa di Pratolino e nei giardini del castello dei Gondi a Noisy-le-Roi The “Libro delle bestie di Firenze e fabbrica di Pratolino” of 1575 which is kept at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, includes the name of the Gondi as administrators of the accounts of the construction. In the same period in Noisy-le-Roi, on the hill north of the valley of Versailles and on the edge of the Marly forest, Alberto Gondi (1522-1602), Duke of Retz and Marshal of France, right arm of the Queen mother, commissioned the construction of a castle with large gardens, which was later destroyed. In Noisy, Alberto Gondi began the construction of a grotto represented in a series of engravings by Jean Marot (1619-1679), but the recent archaeological excavations carried out in 2017 by Bruno Bentz, show that the architectural plan was possibly inverted. In the creation of the grotto, evidence was found of Florentine craftsmanship and the mixing of Italian models with the French . Michel de Montaigne, nel suo Viaggio in Italia clude il nome di Alfonso Gondi come ammini- competere con una residenza principesca7. Co- tra il 1580 e il 1581, esalta il primato mediceo stratore dei conti della costruzione e quello di me nel limitrofo castello di Wideville costruito nel campo delle invenzioni delle grotte1. Si de- “Tommaso di Gio. Parigi in assenza di Alfonso intorno al 1580 per Benoît Milon intendente di ve a Francesco I de’ Medici (1541-1587) com- Gondi”4, permettendo di supporre una cono- finanze di Enrico III, la cui -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

San Sebastiano N

La relazione del Provveditore renze.it pag. 24-25 www.misericordia.fi anno 65° n. 256 Luglio-Agosto-Settembre 2013 256 Luglio-Agosto-Settembre anno 65° n. 1,00 € Sebastiano A Firenze Ecco come Maracchi: il Rinascimento Internet l’Ente Cassa e i suoi geni ha cambiato e le strategie in una mostra la nostra vita contro la crisi a pag. 4-5 a pag. 12-13 a pag. 20-22 San Trimestrale sped. abb. post. 45%-art.3 - comma 20 lettera b Legge 662/96 - Filiale di Firenze post. abb. sped. Trimestrale Periodico della MisericordiaPeriodico di Firenze San Sebastiano_256_Coperta.indd 1 07/06/13 10.36 novità per l’udito Tornare a sentire come prima. L’obiettivo del nuovo microchip per l’udito INIUM. A differenza dei chip tradizionali che amplificano tutti i suoni (voce e rumore) rendendo il tutto sì più forte, ma meno chiaro e distinto; INIUM fa una cosa completamente diversa. Amplifica, cioè alza il volume della voce e riduce il disturbo del rumore che ne ostacola la comprensione. Un trattamento del suono che privilegia due aspetti: capire la voce ed essere molto confortevole. Inoltre la tecnologia wireless di INIUM consente il collegamento senza fili ai moderni dispositivi di comunica- zione quali televisioni, cellulari, computer, lettori MP3 ecc. INIUM è la piattaforma wireless di 3° generazione per una garanzia di funzionamento senza uguali e una continua evoluzione tecnologica per aiutare a sentire come prima e restituire tutto il potenziale uditivo. YOU MATIC: ORA L’UDITO SI MIGLIORA CON IL COMPUTER Si chiama YouMatic la nuova procedura di regolazione su misura degli apparecchi acustici. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

Celebrating the City: the Image of Florence As Shaped Through the Arts

“Nothing more beautiful or wonderful than Florence can be found anywhere in the world.” - Leonardo Bruni, “Panegyric to the City of Florence” (1403) “I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” - Stendahl, Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817) “Historic Florence is an incubus on its present population.” - Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence (1956) “It’s hard for other people to realize just how easily we Florentines live with the past in our hearts and minds because it surrounds us in a very real way. To most people, the Renaissance is a few paintings on a gallery wall; to us it is more than an environment - it’s an entire culture, a way of life.” - Franco Zeffirelli Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 Celebrating the City, page 2 Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 The citizens of renaissance Florence proclaimed the power, wealth and piety of their city through the arts, and left a rich cultural heritage that still surrounds Florence with a unique and compelling mystique. This course will examine the circumstances that fostered such a flowering of the arts, the works that were particularly created to promote the status and beauty of the city, and the reaction of past and present Florentines to their extraordinary home. In keeping with the ACM Florence program‟s goal of helping students to “read a city”, we will frequently use site visits as our classroom. -

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE of MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, and the USE of CULTURAL HERITAGE in SHAPING the RENAISSANCE by NICHOLAS J

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE OF MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, AND THE USE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SHAPING THE RENAISSANCE By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP A thesis submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. and approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Florentine House of Medici (1389-1743): Politics, Patronage, and the Use of Cultural Heritage in Shaping the Renaissance By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP Thesis Director: Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. A great many individuals and families of historical prominence contributed to the development of the Italian and larger European Renaissance through acts of patronage. Among them was the Florentine House of Medici. The Medici were an Italian noble house that served first as the de facto rulers of Florence, and then as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, from the mid-15th century to the mid-18th century. This thesis evaluates the contributions of eight consequential members of the Florentine Medici family, Cosimo di Giovanni, Lorenzo di Giovanni, Giovanni di Lorenzo, Cosimo I, Cosimo II, Cosimo III, Gian Gastone, and Anna Maria Luisa, and their acts of artistic, literary, scientific, and architectural patronage that contributed to the cultural heritage of Florence, Italy. This thesis also explores relevant social, political, economic, and geopolitical conditions over the course of the Medici dynasty, and incorporates primary research derived from a conversation and an interview with specialists in Florence in order to present a more contextual analysis. -

Documents for Ammannati's Neptune Fountain Felicia M

Art and Art History Faculty Publications Art and Art History 7-2005 'La Maggior Porcheria Del Mondo': Documents for Ammannati's Neptune Fountain Felicia M. Else Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/arthfac Part of the Art and Design Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Else, Felicia M. 'La Maggior Porcheria Del Mondo': Documents for Ammannati's Neptune Fountain. The urlB ington Magazine (2005) 147(1228):487-491. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/arthfac/10 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'La Maggior Porcheria Del Mondo': Documents for Ammannati's Neptune Fountain Abstract The ts ory of the creation of the Neptune Fountain on the Piazza della Signoria in Florence is long and tortuous. Scholars have drawn on a wealth of documentary material regarding the competition for the commission, the various phases of the fountain's construction, and the critical reception of its colossus, both political and aesthetic. A collection of unpublished letters at the Getty Research Center in Los Angeles offers a new perspective on the making of this major public monument. Sent by Bartolomeo Ammannati to the prvveditore of Pisa, they chronicle the artist's involvement in the procurement and transportation of marble from Carrara and Seravezza for the chariot and basin of the fountain during the years 1565-73. -

Tommaso De' Cavalieri

TOMMASO DE’ CAVALIERI E L’EREDITÀ DI DANIELE DA VOLTERRA: MICHELE ALBERTI E JACOPO ROCCHETTI NEL PALAZZO DEI CONSERVATORI MARCELLA MARONGIU Tommaso de’ Cavalieri e Daniele da Volterra «Potete esser certo che m. Tomaso del Cavaliere, m. Daniello et io non siamo per mancare in assentia vostra di ogni offitio pos- sibile per honore et utile vostro»1: con queste parole Diomede Leoni intendeva rassicurare Leonardo Buonarroti, nipote ed erede designato di Michelangelo, sulla presenza costante degli amici più cari al capezzale del grande artista. Si tratta del primo Desidero esprimere la mia gratitudine a Barbara Agosti, Maria Beltramini, Silvia Ginz- burg e Vittoria Romani per aver discusso con me alcuni dei problemi affrontati in questo saggio. Ringrazio inoltre Valentina Balzarotti, Eliana Carrara, Anna Corrias, Eva Del Soldato, Emanuela Ferretti, Morten Steen Hansen, Federica Kappler, Elena Lombardi, Liana Meloni, Livia Nocchi, Fernando Piras, Serena Quagliaroli, Anna Ma- ria Riccomini, Massimo Romeri e Giulia Spoltore per avermi generosamente fornito materiali e consigli. Grazie infine a Christine Graffin e Agnès Kayser per le sedute di studio nella chiesa della Santissima Trinità dei Monti, e ad Angela Carbonaro e Claudio Parisi Presicce per l’uso delle immagini. 1 Lettera di Diomede Leoni in Roma a Leonardo Buonarroti in Firenze del 14 febbraio 1564: IL CARTEGGIO INDIRETTO DI MICHELANGELO 1988-1995, vol. II, pp. 172-173, n. 358. La lettera accompagnava un’altra missiva indirizzata a Leonardo Buonarroti, det- tata a Daniele da Volterra e sottoscritta da Michelangelo (14 febbraio 1564): IL CAR- TEGGIO INDIRETTO DI MICHELANGELO 1988-1995, vol. II, pp. 172-173, n.