The FLQ—Was the War Measures Act a Necessity Or an Over-‐ Reaction?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justiceeducation.Ca Lawlessons.Ca Date Reviewed November

#260 – 800 Hornby Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 2C5 Date Reviewed November 2020 Course Social Studies 10 Topic Internments in Canada Big Idea Historical and contemporary injustices challenge the narrative and identity of Canada as an inclusive, multicultural society. Essential Question How have past governments of Canada used laws to discriminate against Canadian citizens? Learning Standards Content: Students are expected to know the following: • discriminatory policies and injustices in Canada and the world Curricular Competencies Students are expected to be able to do the following: • make reasoned ethical judgments about actions in the past and present, and assess appropriate ways to remember and respond Core Competencies Communication - I can describe how the War Measures Act discriminated against some Canadians based on their race, ethnicity, religion, and political beliefs. Thinking – I can make judgements about past discriminatory policies and assess how current legislation protects rights and freedoms. Personal and Social – I can explain the importance of balancing individual rights with the need to protect security and order. JusticeEducation.ca LawLessons.ca First People’s Principles of Learning • Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one’s actions. Introduction • Show the video (11:16) Japanese Canadian Internment narrated by David Suzuki. • Have students complete the Viewing Guide: Japanese Canadian Internment. Go over using Answer Key—Viewing Guide: Japanese Canadian Internment. • Engage students in a discussion of whether Japanese Canadians posed a real threat during World War Two. Pre-Assessment • Explain that the term “enemy alien” referred to people from countries, or with roots in countries, that were at war with Canada. • Have students list countries that were at war with Canada during World War Two. -

The October Crisis, 1970

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 3 August 2013 Lifting the Veil of Violence: The cO tober Crisis, 1970. Jef R. Palframan Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Palframan, Jef R. (2013) "Lifting the Veil of Violence: The ctO ober Crisis, 1970.," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lifting the Veil of Violence: The cO tober Crisis, 1970. Cover Page Footnote The uthora wishes to thank as participants of the Oglethorpe University Honors Program Dr. N. Maher, Dr. R. Bobroff, Dr. Wm. Smith, Dr. J. Lutz, Dr. C. Copeland, Dr. P. Kower, Dr. S. Shrikhande and Dr. M. Rulison for their professional and wholehearted support during this project. This work is dedicated to always faithful and dedicated Mrs. Krista Palframan. For further information and inquiries please contact the author at [email protected]. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss2/3 Palframan: Lifting the Veil of Violence: The October Crisis, 1970. Introduction In October of 1970, Canada stood still as terror and civil unrest directly challenged the unity of the country. -

The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question

CHC2D1 The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question Eight Lessons on Historical Thinking Concepts: Evidence, Significance, Perspective, Ethical Issues, Continuity and Change, and Cause and Consequence CURR335 Section 002 November 15, 2013 Prepared for Professor Theodore Christou B.A.H., M.A., P.h.D Prepared by: Derek Ryan Lachine Queen’s University Lesson 1: Introductory Lesson The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: The Sovereignty Question “Vive le Quebec libre!” 1 Class 1. Overview This lesson will ask students to ponder the meaning of separatism and engage with source material to understand how “Vive le Quebec libre” would have been perceived during the Quiet Revolution. This lesson will introduce the students to important people, terms, and ideas that will aid them in assessing how the separatist movement blossomed during the 60s, and what it meant in the eventual blow-up that would be the October Crisis of 1970. 2. Learning Goal To hypothesiZe how separatism can be viewed from an Anglo-Canadian and French- Canadian perspective. Demonstrate what line of thought your understanding and/or definition of separatism falls under: the Anglo, the French or the fence. Express educated hypotheses as to why French-Canadians would have found solidarity in Charles de Gaulle’s words, “Vive le Quebec libre”. 3. Curriculum Expectations a) A1.5- use the concepts of historical thinking (i.e., historical significance, cause and consequence, continuity and change, and historical perspective) when analyZing, evaluating evidence about, and formulating conclusions and/or judgements regarding historical issues, events, and/or developments in Canada since 1914 b) Introductory lesson: engage with preliminary ideas of separatism and how different regions of Canada show different perspectives towards Quebec nationalism. -

Background to Japanese Internment Historic Injustices and Redress in Canada

Background to Japanese internment Historic injustices and redress in Canada Details about Japanese internment Immediately following Japan’s attack on Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Canada, like its ally, the United States, declared war on Japan. The War Measures Act was passed, making every Japanese person in Canada, regardless of where they were born and whether they were a citizen of Canada or not, an enemy alien. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the lives of Japanese Impounded Japanese Canadian fishing vessels at Annieville Dyke on the Canadians changed dramatically. Many lost their Fraser River in the early 1940s. Source: University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books and Special jobs, their fishing boats were seized, and Japanese Collections, JCPC 12b.001. cultural organizations and newspapers were closed. Curfews were imposed, and a “secure zone” that Historical context excluded Japanese men, was set up along the west During the late 1800s, many young Japanese men coast. left lives of extreme poverty in Japan in search of a Of the over 23,000 Japanese in Canada at the better future. Some ended up in Canada, mostly on time, more than 75% were Canadian citizens. All the west coast, only to face new hardships and an were labeled enemy aliens. Local newspapers unwelcoming society. Many were already skilled and radio stations continuously reported that fishermen in Japan and a few found work in the Japanese spies were in their communities and fishing industry on the west coast, either in the would help the enemy when they invaded. In early boats or at one of the dozens of canneries where 1942, the Canadian government ordered Japanese the fish were processed and canned. -

Italian Canadian Experiences During World War Ii

ITALIAN CANADIAN EXPERIENCES DURING WORLD WAR II he early population of Niagara Falls was largely of government unlimited powers to protect the state from any British origin, but from around the 1880s, this began internal or external threats, to ban subversive political T to change with a new influx of peoples of European organizations and to suspend foreign-language newspapers. It background. The construction boom that created railways, a also allowed for the internment of Canadian residents born in post office, fire hall, street car system, steam electric countries or empires at war with Canada. When Canada generating plant, water works and numerous churches formally declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, attracted mainly Italian immigrants. Later on, with the turn-of around 850 German-Canadians were interned and over 66,000 -the-century hydro electric plants at the Falls, more Germans, German and Austrian Canadians (naturalized citizens) who had Hungarians, Ukrainians, Polish and others began to arrive as well. arrived in Canada after 1922, were forced to report to the police regularly. Later, when Italy entered the war on the side The growing close-knit Italian community opened of the Germans, the Canadian government gave the Royal new commercial establishments: groceries, barbershops, shoe Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) orders to arrest Italian repairs, etc., to meet their needs. They settled together, Canadians considered to be a security risk. Of the approximate largely according to their areas of origin, in neighbourhoods in 112,625 Italian-Canadian residents in Canada, 31,000 were Clifton, Drummondville and the Glenview area. The first Italian organization came in 1912 with the construction of St. -

REDRESS MOVEMENTS in CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo

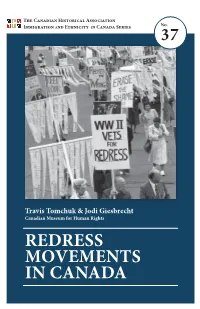

The Canadian Historical Association No. Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series 37 Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures on behalf of all levels of government in Canada in order to acknowledge the historic wrongs suffered by diverse ethnic and immigrant groups. -

1 the October Crisis Appendix D

1 The October Crisis Appendix D “The October Crisis per se – (in chronological order - 5 October to 29 December 1970)” I. The FLQ on 5 October 1970 By 5 October 1970, the FLQ have committed over 200 criminal acts, including thefts, robberies, hold-ups and bombings and were responsible for six violent deaths: Wilfred (Wilfrid) O’Neill (O’Neil) (21 April 1963); Leslie McWilliams and Alfred Pinisch (29 August 1964); Thérèse Morin (5 May 1966); Jean Corbo (16-year-old FLQ member killed by an FLQ bomb, 14 July 1966); and Jeanne d’Arc Saint-Germain (24 June 1970). On 5 October 1970, 20 terrorists are in jail, either awaiting trial or having been convicted for acts of terrorism, being: François Schirm, Edmond Guénette, Cyriaque Delisle, Serge Demers, Marcel Faulkner, Gérard Laquerre, Robert Lévesque, Rhéal Mathieu, Claude Simard, Pierre-Paul Geoffroy, Gabriel and Robert Hudon, Pierre Demers, Marc-André Gagné, François Lanctôt, André Roy, Claude Morency; Pierre Boucher, Michel Loriot and André Ouellette. At least three others (Pierre Marcil, Réjean Tremblay and André Lessard) have been arrested but are free on bail. Throughout the ensuing negotiations between the Government of Quebec (as represented by Robert Demers) and the FLQ (as represented by Robert Lemieux), the exact number of jailed terrorists implicated was not clear, because at least one did not wish to go to Cuba, as Robert Lemieux discovered when he visited the prisoners on behalf of the FLQ. 2 II. The FLQ Decides To Proceed by Kidnappings In 1970, the FLQ decides to proceed to political kidnappings, as the next step towards the expected insurrection. -

Internment of Ukrainians in Canada 1914-1920

Internment of Ukrainians in Canada 1914-1920 Immigration to Canada z Between 1891 and 1914, approximately 170,000 Ukrainians immigrated to Canada, from the Western Ukrainian regions of Halychyna* and Bukovyna, enticed by the offer of free land and a better life on the Canadian prairies. *also called Galicia, using the Polish term. Mistaken Identity z During this time, the regions (oblasts) of L’viv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Chernivtsi were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ukrainians immigrants from these regions were labelled as “Austrian” or “Austro-Hungarian”. (Area # 6 and #2 on the map) Note: Lemberg = Lviv; Czernowitz = Chernivtsi “Enemy Aliens” z In 1914, through the War Measures Act, Canada issued an order for registration and in certain cases, internment of individuals who were considered to be of ‘enemy nationality’ to Canada. z Austria was not an ally of Canada during the war. Therefore, many Ukrainians and other East European immigrants were described as Austrian “enemy aliens” by the Canadian government. Tracking Immigrants z As many as 80,000 Ukrainians were forced to carry identity documents and report regularly to government authorities. z Over 9,000 men, women and children were interned in 24 concentrations camps across Canada. Approximately 5,000 of those interned were Ukrainian. Internment Camps Lives Altered z Ukrainian immigrants lost trust in the government after having their activities tracked and their loyalty to Canada questioned. z Some Ukrainians were deported after the war. Others changed their names to hide the shame of being interned from their children. z The ethnic pride and self-image of Ukrainians in Canada was negatively affected because of their internment as war criminals. -

The Historiography of the Front De Liberation Du Quebec: Frameworks, ‘Identity’ and Future Study Kevin Lee Pinkoski

The Historiography of the Front de Liberation du Quebec: Frameworks, ‘Identity’ and Future Study Kevin Lee Pinkoski This paper examines the historiography of the Front de Liberation Quebecois within the context of three frameworks, each used to devaluate the FLQ, the idea of separation, its potential support and most importantly, the perspectives of historians who oppose these frameworks. Through an examination of the literature, the FLQ are framed as an attack on British liberalism, an attack on Canadian Unity, or violent in a political climate where such actions were unjustifiable. These understandings work cooperatively together to de-legitimize alternative views on FLQ history, and Quebec independence. I will examine also the benefits in studying the FLQ outside of the tensions of separation and the potential for future study in the history of the FLQ. During the 1960s and 1970s, Quebec was exposed to the potential of its own national identity. The realization of this identity took place through the Quiet Revolution, the creation of the Parti Quebecois, and citizen activism towards the goal of independence from Canada. An example of this activism is the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ), generally characterized as a protesting terrorist group. Terrorism in this sense can be described as a desire to achieve political change by obtaining power through violence in order to right a perceived wrong. 1 In the case of the FLQ, this violence was most recognizable in the kidnappings of James Cross and Pierre Laporte, culminating in the 1970 October Crisis (which resulted in the enactment of The War Measures Act), the 1969 bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange, and almost 160 other violent incidents attributed to or claimed by the FLQ, killing a total of eight individuals.2 However, the majority of historians do not focus their analysis on the development of violence as a means of political expression within a specific social climate, but rather focus on understanding the FLQ as an attack on Canadian „values‟ and „identity‟. -

History Prep Activities.Pdf

Jr. Plar History Prep Work 2016 KPRDSB TASK 1 - THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ROLE OF WOMEN IN EARLY 20TH CENTURY Read the following and answer the questions below. Prohibition in Canada was the result of several movements, and various things happening in the time period of WWI. The fight against alcohol, or the Temperance Movement, began as early as the 1860’s. Many of those advocating for the temperance movement were religious groups and women, though not in all of Canada’s provinces. Another movement taking place before and during WWI was the Women’s Suffrage Movement. As women sought more social and political equality, one obvious problem was the right of suffrage, or the right to vote. These two movements in the late 19th century and early 20th century came to completion in Canada during WWI. Many women (and men, but mostly women) in Canada had been pressing the government to prohibit the sale, manufacturing and exportation of liquor in Canada through social and religious groups, but could not vote federally or provincially, making it very difficult to pass legislation. Women argued that excessive drinking by men ruined family life and led to much domestic violence. But alcohol wouldn't likely be abolished, they said, until women got the vote. In Canada, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union was a leading voice in the battle for the vote. However, the government was not enthusiastic about prohibition nor giving the women the right to vote, since it would cause loss of tax revenue and party support. A large number of Canadian men including politicians supported the right for women to vote but the movement still needed a breakthrough. -

Canada and the First World War GUIDING QUESTIONS

02_Ch02_CP11_2e_se_F.qxd:Layout 1 4/13/10 1:43 PM Page 24 2 Canada and the First World War GUIDING QUESTIONS Society & Identity ● What challenges did Aboriginal soldiers face during the war and upon their return home? ● What effect did the War Measures Act have on the legal rights of Canadians? ● How did Canada’s contribution on the battlefield affect Canadian identity? ● What effect did the war have on the role of women? ● What impact did conscription have on Canadian unity? Autonomy & World Presence ● How did Canada get involved in the First World War? ● What was the war’s impact on the home front? ● How did the nature of warfare and technology contribute to a war of attrition? ● What were conditions like for men in the trenches? ● Describe Canada’s military role in the First World War. ● What factors contributed to Canada’s emerging autonomy? TIMELINE 1914 1915 1916 Archduke Franz Ferdinand assassinated in Sarajevo Canadian troops exposed to Canadians suffer heavy losses in Germany invades Belgium and France poisonous gas at the Battle of Ypres the Battle of the Somme Britain declares war on Germany; Canada Women in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, automatically at war and Alberta gain the right to vote in provincial elections War Measures Act passed in Canada 24 Unit 1 ■ Canada in Transition: A Nation Emerges ©P 02_Ch02_CP11_2e_se_F.qxd:Layout 1 4/13/10 1:27 PM Page 25 CHAPTER FOCUS QUESTION Significance Patterns and Change What effect did Canada’s participation in the First World War have on Canadian society and its status as a nation? Judgements CRITICAL Evidence INQUIRY Cause and Consequence Perspectives When the First World War began in 1914, few believed it would last very long. -

The Centre Cannot Hold: Pierre Trudeau, the War Measures Act, and the Nature of Prime Ministerial Power

Paper presented to the conference of the Canadian Political Science Association June 1-3 2010, Montreal The Centre Cannot Hold: Pierre Trudeau, the War Measures Act, and the Nature of Prime Ministerial Power H.D. Munroe1,2 Abstract: The notion that the Prime Minister of Canada has become an autocracy is common in popular discourse. Some, such as Savoie, suggest that Pierre Trudeau marked the beginnings of this trend. Bakvis, and to a lesser extent Aucoin, hold alternate views of Prime Ministerial power in which Trudeau represents continuity rather than change. This paper draws on archival research and interviews with former cabinet ministers to explore the nature of Prime Ministerial power at a pivotal moment in Trudeau’s first term: The invocation of the War Measures Act in October of 1970. The analysis finds that Trudeau was far less autocratic than is generally believed, that the empirical foundations of Savoie’s argument may need re-examining, and that federalism is a significant constraint on the exercise of Prime Ministerial power. The extent and nature of the power of the Prime Minister is a topic of perennial discussion in Canadian politics (Matheson, 1976; Schindeler, cited in Hockin, 1977; Aucoin, 1986; Savoie, 1999a; Savoie, 1999b; Bakvis, 2001), particularly in popular discourse, where the tropes of the Prime Minister as autocrat or Canada as “elected dictatorship” have enjoyed enduring popularity (Hockin, 1977; Bakvis, 2001; Savoie, 2008: 49). Unsurprisingly, the academy has produced more nuanced understandings of the nature of Prime Ministerial power - but even here there is hardly consensus. Savoie’s work (1999a; 1999b; 2008) portrays a Prime Minister who effectively personifies executive power at the expense of cabinet, while Bakvis (2001) holds that while Prime Ministers have always had more power than the notion of ‘first among equals’ implies, the idea of Prime Minister as autocrat exaggerates the power of the office.