Background to Japanese Internment Historic Injustices and Redress in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource List

BEING JAPANESE CANADIAN: reflections on a broken world RESOURCE LIST This list of resources was prepared by the co-curators for Being Japanese Canadian and the East Asian Librarian at the ROM. Our intention is not to be comprehensive, but instead, to provide an introductory selection of accessible resources expanding on themes and issues explored by artists in the exhibit. There are examples of historical scholarship, popular writing, literature for all ages and multimedia addressing the multifaceted ramifications of the uprooting, exile and incarceration of Japanese Canadians during the 1940s. All resources were alphabetized and annotated by the team with descriptive comments. Resource list accompanying Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world ROM Exhibition, February 2 to August 5, 2019 1 HISTORICAL TEXTS Adachi, Ken. 1979. The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Canada’s Peoples. Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart. A landmark text, Adachi’s book is one of the first to discuss the history of racism toward people of Japanese descent living in Canada. Hickman, Pamela, and Masako Fukawa. 2012. Righting Canada’s Wrongs: Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War. Toronto, ON: James Lorimer & Company. Written for readers 13 and over, this book is part of a series created to present historical events where the Canadian Government has acknowledged discriminatory actions. Illustrated with historical photographs, anecdotes, items and documents, this accessibly written book is suitable for youth at the middle and junior high school level. Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre: Heritage Committee. Just Add Shoyu: A Culinary Journey of Japanese Canadian Cooking. 2010. Toronto, ON, Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. -

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 19:58 International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending Citizens of Japanese Ancestry in North America, 1942–49. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Caccia, Ivana. Managing the Canadian Mosaic in Wartime: Shaping Citizenship Policy, 1939–1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Champion, C.P. The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism, 1964–68. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Iacovetta, Franca. Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006 Kaprielian-Churchill, Isabel. Like Our Mountains: A History of Armenians in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005 Lambertson, Ross. Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930–1960. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005 MacLennan, Christopher. Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929–1960. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004 Roy, Patricia E. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941–67. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Christopher G. Anderson Miscellaneous: International Perspectives on Canada En vrac : perspectives internationales sur le Canada Numéro 43, 2011 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1009461ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1009461ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Conseil international d’études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (imprimé) 1923-5291 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Anderson, C. G. (2011). Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective / Bangarth, Stephanie D. -

The FLQ—Was the War Measures Act a Necessity Or an Over-‐ Reaction?

The FLQ—Was the War Measures Act a Necessity or an Over- reaction? Concept(s) Primary Source Evidence Prepared for Grade(s) 10, 11, 12 Province NB By Stephen Wilson Time Period(s) 1900-present Time allotment Three 60 minute periods Brief Description of the Task Students will examine a series of photographs, videos and accounts detailing the activities of the FLQ throughout the 1960's and culminating in the October Crisis of 1970. From these various documents, students will assess the necessity of the invocation of the War Measures Act in 1970 and develop an historical argument explaining why they think the use of this act was justified or not justified at this point in Canadian history. Objectives Students will arrive at and defend a conclusion using multiple primary and secondary sources by: 1. identifying whether each document is a primary or secondary source. 2. identifying the providence. 3. assessing the reliability. 4. drawing inferences from each source about the question they are trying to answer. 5. checking for corroboration with other sources. 6. offering a conclusion that clearly and specifically answers the question offered for consideration. 7. supporting the conclusion with evidence from the various sources. In a broader sense, students should 1. appreciate that historians are selective in the questions they seek to answer and the evdence they use. 2. recognize that interpretation is an essential ingredient of history. 3. employ processes of critical historical inquiry to reconstruct and interpret the past. 4. challenge arguments of historical inevitability. Required Knowledge & Skills It would enhance the lesson if students already were able to do the following: 1. -

Justiceeducation.Ca Lawlessons.Ca Date Reviewed November

#260 – 800 Hornby Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6Z 2C5 Date Reviewed November 2020 Course Social Studies 10 Topic Internments in Canada Big Idea Historical and contemporary injustices challenge the narrative and identity of Canada as an inclusive, multicultural society. Essential Question How have past governments of Canada used laws to discriminate against Canadian citizens? Learning Standards Content: Students are expected to know the following: • discriminatory policies and injustices in Canada and the world Curricular Competencies Students are expected to be able to do the following: • make reasoned ethical judgments about actions in the past and present, and assess appropriate ways to remember and respond Core Competencies Communication - I can describe how the War Measures Act discriminated against some Canadians based on their race, ethnicity, religion, and political beliefs. Thinking – I can make judgements about past discriminatory policies and assess how current legislation protects rights and freedoms. Personal and Social – I can explain the importance of balancing individual rights with the need to protect security and order. JusticeEducation.ca LawLessons.ca First People’s Principles of Learning • Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one’s actions. Introduction • Show the video (11:16) Japanese Canadian Internment narrated by David Suzuki. • Have students complete the Viewing Guide: Japanese Canadian Internment. Go over using Answer Key—Viewing Guide: Japanese Canadian Internment. • Engage students in a discussion of whether Japanese Canadians posed a real threat during World War Two. Pre-Assessment • Explain that the term “enemy alien” referred to people from countries, or with roots in countries, that were at war with Canada. • Have students list countries that were at war with Canada during World War Two. -

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Jeong Mi Lee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto O Copyright by Jeong Mi Lee 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AW OnawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing tk exclusive permettant a la National Lïbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Master of Arts, 1999 Jeong Mi Lee Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto Abstract Canada consists of immigrants from al1 over the world - and it creates diverse cultures in one society. Arnong them, Asian immigrants from China and Japan have especially experienced many difficulties in the early period. -

The October Crisis, 1970

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 3 August 2013 Lifting the Veil of Violence: The cO tober Crisis, 1970. Jef R. Palframan Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Palframan, Jef R. (2013) "Lifting the Veil of Violence: The ctO ober Crisis, 1970.," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lifting the Veil of Violence: The cO tober Crisis, 1970. Cover Page Footnote The uthora wishes to thank as participants of the Oglethorpe University Honors Program Dr. N. Maher, Dr. R. Bobroff, Dr. Wm. Smith, Dr. J. Lutz, Dr. C. Copeland, Dr. P. Kower, Dr. S. Shrikhande and Dr. M. Rulison for their professional and wholehearted support during this project. This work is dedicated to always faithful and dedicated Mrs. Krista Palframan. For further information and inquiries please contact the author at [email protected]. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol2/iss2/3 Palframan: Lifting the Veil of Violence: The October Crisis, 1970. Introduction In October of 1970, Canada stood still as terror and civil unrest directly challenged the unity of the country. -

The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question

CHC2D1 The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question Eight Lessons on Historical Thinking Concepts: Evidence, Significance, Perspective, Ethical Issues, Continuity and Change, and Cause and Consequence CURR335 Section 002 November 15, 2013 Prepared for Professor Theodore Christou B.A.H., M.A., P.h.D Prepared by: Derek Ryan Lachine Queen’s University Lesson 1: Introductory Lesson The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: The Sovereignty Question “Vive le Quebec libre!” 1 Class 1. Overview This lesson will ask students to ponder the meaning of separatism and engage with source material to understand how “Vive le Quebec libre” would have been perceived during the Quiet Revolution. This lesson will introduce the students to important people, terms, and ideas that will aid them in assessing how the separatist movement blossomed during the 60s, and what it meant in the eventual blow-up that would be the October Crisis of 1970. 2. Learning Goal To hypothesiZe how separatism can be viewed from an Anglo-Canadian and French- Canadian perspective. Demonstrate what line of thought your understanding and/or definition of separatism falls under: the Anglo, the French or the fence. Express educated hypotheses as to why French-Canadians would have found solidarity in Charles de Gaulle’s words, “Vive le Quebec libre”. 3. Curriculum Expectations a) A1.5- use the concepts of historical thinking (i.e., historical significance, cause and consequence, continuity and change, and historical perspective) when analyZing, evaluating evidence about, and formulating conclusions and/or judgements regarding historical issues, events, and/or developments in Canada since 1914 b) Introductory lesson: engage with preliminary ideas of separatism and how different regions of Canada show different perspectives towards Quebec nationalism. -

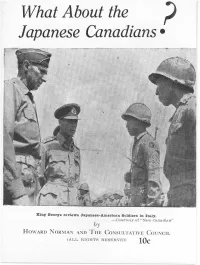

What About Japanese Canadians

Page Fou,. · INTRODUCTION "Somewhere in B. C., , April 23, 1945. "Dear' -' --: "" ,,'. •.. We are in a state of nerves anci an~if!ty about all this ¥phuitary repatriation or go east (i.e., of the Rockies). Roy is interpreting secretary for the committee here and has to go to all meetings, interviews, etc., though we know , it is useless to protest. $() ,lUany have signed to go to Japan; about 95 per cent at Lenion Creek, 'because all that goes with signing that, is so much more ~i:lY~iJ1ageous than going east, but we have decided to go east. I w'o'Md' gladly go east except for one thing. The clause which says 'subject to relocation again after the war'. Do we have to move again then? Oh, Lord, when will this thing ever close! It means . every ~inie we move we have to leave all the improvements we have n'ladeahd start allover again. The financial loss is considerable beside all the work, we have put into it. LaSt year we made a new kitchen with new linoleum, large windows, even a door with glass ~ri.\:Fpiped ill our OWll water from quite a distance and now, less than eight months, and off we go again. "Roy has' a 'chance to go as a sawyer at $l.00 an hour, north of Kamloops, but he can't go unless he signs to go to Japan. If he iigns to go east, X is waiting in the next room to push a job into your face. If you refuse to take it, you lose your job here and maintenance when Roy's not working... -

Timeline of Social and Cultural Injustices in Canada

Timeline of Social and Cultural Injustices 9.1.4 c in Canada 1876 The Indian Act is established and controls many aspects of First Nations persons’ lives, from birth to death. Indian Bands are created and many decisions are made by the federal government about the relocation of First Nations. (Since then, the Indian Act has undergone many amendments. Until 1951, laws defined a person as "an individual other than an Indian." Indians could obtain the right to vote by renouncing their Indian status, and were not considered to have the same rights as citizens until 1960.) 1884 Aboriginal potlatch celebrations are made illegal under the Indian Act. 1880s–1996 The Indian Act is amended to give responsibility for the education of children to mostly church-run residential schools. The law required compulsory attendance for those status Indians under the age of 16 until they reached 18 years of age in Indian schools. There were 130 residential schools in Canada. Most residential schools ceased to operate by the mid-1970s; the last federally run residential school in Canada closed in 1996. 1885 As Chinese labourers are no longer needed to work on building the railways, the Chinese Immigration Act sets a head tax of $50 on every Chinese person entering Canada. 1890, March 18 The Manitoba legislature passes the Official Language Act to abolish the official status of the French language that is used in the Legislature, laws, records, journals and courts. This was in violation of the Manitoba Act of 1870 which declared English and French as official languages in Manitoba*. -

The Evacuation of the Japanese Canadians, 1942: a Realist Critique of the Received Version

The Evacuation of the Japanese Canadians, 1942: A Realist Critique of the Received Version J.L. Granatstein and Gregory A. Johnson The popularly accepted version of the evacuation of the Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast in 1941-1942 and the background to it runs roughly like this. The white population of British Columbia had long cherished resentments against the Asians who lived among them, and most particularly against the Japanese Canadians. Much of this sprang from envy of the Japanese Canadians' hard-work and industry, much at the substantial share held by Japanese Canadians of the fishing, market gardening and lumbering industry. Moreover, white British Columbians (and Canadians generally) had long had fears that the Japanese Canadians were unassimilable into Canadian society and, beginning early in this century and intensifying as the interwar period wore on, that many might secretly be acting as agents of their original homeland, now an aggressive and expansionist Japan. Liberal and Conservative politicians at the federal, provincial and municipal levels played upon the racist fears of the majority for their own political purposes. Thus when the Second World War began in September 1939, and when its early course ran disastrously against the Allies, there was already substantial fear about "aliens" in British Columbia (and elsewhere) and a desire to ensure that Japanese Canadians would be exempted from military training and service. The federal government concurred in this, despite the desire of many young Japanese Canadians to show their loyalty to Canada by enlisting. After 7 December 1941 and the beginning of the Pacific War, public and political pressures upon the Japanese Canadians increased exponentially. -

Italian Canadian Experiences During World War Ii

ITALIAN CANADIAN EXPERIENCES DURING WORLD WAR II he early population of Niagara Falls was largely of government unlimited powers to protect the state from any British origin, but from around the 1880s, this began internal or external threats, to ban subversive political T to change with a new influx of peoples of European organizations and to suspend foreign-language newspapers. It background. The construction boom that created railways, a also allowed for the internment of Canadian residents born in post office, fire hall, street car system, steam electric countries or empires at war with Canada. When Canada generating plant, water works and numerous churches formally declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, attracted mainly Italian immigrants. Later on, with the turn-of around 850 German-Canadians were interned and over 66,000 -the-century hydro electric plants at the Falls, more Germans, German and Austrian Canadians (naturalized citizens) who had Hungarians, Ukrainians, Polish and others began to arrive as well. arrived in Canada after 1922, were forced to report to the police regularly. Later, when Italy entered the war on the side The growing close-knit Italian community opened of the Germans, the Canadian government gave the Royal new commercial establishments: groceries, barbershops, shoe Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) orders to arrest Italian repairs, etc., to meet their needs. They settled together, Canadians considered to be a security risk. Of the approximate largely according to their areas of origin, in neighbourhoods in 112,625 Italian-Canadian residents in Canada, 31,000 were Clifton, Drummondville and the Glenview area. The first Italian organization came in 1912 with the construction of St.