Towards a First Nations-Japan Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource List

BEING JAPANESE CANADIAN: reflections on a broken world RESOURCE LIST This list of resources was prepared by the co-curators for Being Japanese Canadian and the East Asian Librarian at the ROM. Our intention is not to be comprehensive, but instead, to provide an introductory selection of accessible resources expanding on themes and issues explored by artists in the exhibit. There are examples of historical scholarship, popular writing, literature for all ages and multimedia addressing the multifaceted ramifications of the uprooting, exile and incarceration of Japanese Canadians during the 1940s. All resources were alphabetized and annotated by the team with descriptive comments. Resource list accompanying Being Japanese Canadian: reflections on a broken world ROM Exhibition, February 2 to August 5, 2019 1 HISTORICAL TEXTS Adachi, Ken. 1979. The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Canada’s Peoples. Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart. A landmark text, Adachi’s book is one of the first to discuss the history of racism toward people of Japanese descent living in Canada. Hickman, Pamela, and Masako Fukawa. 2012. Righting Canada’s Wrongs: Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War. Toronto, ON: James Lorimer & Company. Written for readers 13 and over, this book is part of a series created to present historical events where the Canadian Government has acknowledged discriminatory actions. Illustrated with historical photographs, anecdotes, items and documents, this accessibly written book is suitable for youth at the middle and junior high school level. Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre: Heritage Committee. Just Add Shoyu: A Culinary Journey of Japanese Canadian Cooking. 2010. Toronto, ON, Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. -

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 19:58 International Journal of Canadian Studies Revue internationale d’études canadiennes Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective Bangarth, Stephanie D. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending Citizens of Japanese Ancestry in North America, 1942–49. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Caccia, Ivana. Managing the Canadian Mosaic in Wartime: Shaping Citizenship Policy, 1939–1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Champion, C.P. The Strange Demise of British Canada: The Liberals and Canadian Nationalism, 1964–68. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010 Iacovetta, Franca. Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada. Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006 Kaprielian-Churchill, Isabel. Like Our Mountains: A History of Armenians in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005 Lambertson, Ross. Repression and Resistance: Canadian Human Rights Activists, 1930–1960. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005 MacLennan, Christopher. Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929–1960. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2004 Roy, Patricia E. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941–67. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008 Christopher G. Anderson Miscellaneous: International Perspectives on Canada En vrac : perspectives internationales sur le Canada Numéro 43, 2011 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1009461ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1009461ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Conseil international d’études canadiennes ISSN 1180-3991 (imprimé) 1923-5291 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Anderson, C. G. (2011). Immigration, Immigrants, and the Rights of Canadian Citizens in Historical Perspective / Bangarth, Stephanie D. -

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People

Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Jeong Mi Lee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto O Copyright by Jeong Mi Lee 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AW OnawaON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing tk exclusive permettant a la National Lïbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Asian Minorities in Canada: Focusing on Chinese and Japanese People Master of Arts, 1999 Jeong Mi Lee Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto Abstract Canada consists of immigrants from al1 over the world - and it creates diverse cultures in one society. Arnong them, Asian immigrants from China and Japan have especially experienced many difficulties in the early period. -

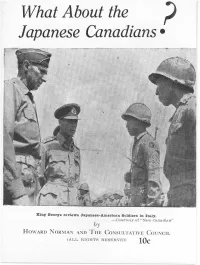

What About Japanese Canadians

Page Fou,. · INTRODUCTION "Somewhere in B. C., , April 23, 1945. "Dear' -' --: "" ,,'. •.. We are in a state of nerves anci an~if!ty about all this ¥phuitary repatriation or go east (i.e., of the Rockies). Roy is interpreting secretary for the committee here and has to go to all meetings, interviews, etc., though we know , it is useless to protest. $() ,lUany have signed to go to Japan; about 95 per cent at Lenion Creek, 'because all that goes with signing that, is so much more ~i:lY~iJ1ageous than going east, but we have decided to go east. I w'o'Md' gladly go east except for one thing. The clause which says 'subject to relocation again after the war'. Do we have to move again then? Oh, Lord, when will this thing ever close! It means . every ~inie we move we have to leave all the improvements we have n'ladeahd start allover again. The financial loss is considerable beside all the work, we have put into it. LaSt year we made a new kitchen with new linoleum, large windows, even a door with glass ~ri.\:Fpiped ill our OWll water from quite a distance and now, less than eight months, and off we go again. "Roy has' a 'chance to go as a sawyer at $l.00 an hour, north of Kamloops, but he can't go unless he signs to go to Japan. If he iigns to go east, X is waiting in the next room to push a job into your face. If you refuse to take it, you lose your job here and maintenance when Roy's not working... -

Background to Japanese Internment Historic Injustices and Redress in Canada

Background to Japanese internment Historic injustices and redress in Canada Details about Japanese internment Immediately following Japan’s attack on Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Canada, like its ally, the United States, declared war on Japan. The War Measures Act was passed, making every Japanese person in Canada, regardless of where they were born and whether they were a citizen of Canada or not, an enemy alien. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the lives of Japanese Impounded Japanese Canadian fishing vessels at Annieville Dyke on the Canadians changed dramatically. Many lost their Fraser River in the early 1940s. Source: University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books and Special jobs, their fishing boats were seized, and Japanese Collections, JCPC 12b.001. cultural organizations and newspapers were closed. Curfews were imposed, and a “secure zone” that Historical context excluded Japanese men, was set up along the west During the late 1800s, many young Japanese men coast. left lives of extreme poverty in Japan in search of a Of the over 23,000 Japanese in Canada at the better future. Some ended up in Canada, mostly on time, more than 75% were Canadian citizens. All the west coast, only to face new hardships and an were labeled enemy aliens. Local newspapers unwelcoming society. Many were already skilled and radio stations continuously reported that fishermen in Japan and a few found work in the Japanese spies were in their communities and fishing industry on the west coast, either in the would help the enemy when they invaded. In early boats or at one of the dozens of canneries where 1942, the Canadian government ordered Japanese the fish were processed and canned. -

Timeline of Social and Cultural Injustices in Canada

Timeline of Social and Cultural Injustices 9.1.4 c in Canada 1876 The Indian Act is established and controls many aspects of First Nations persons’ lives, from birth to death. Indian Bands are created and many decisions are made by the federal government about the relocation of First Nations. (Since then, the Indian Act has undergone many amendments. Until 1951, laws defined a person as "an individual other than an Indian." Indians could obtain the right to vote by renouncing their Indian status, and were not considered to have the same rights as citizens until 1960.) 1884 Aboriginal potlatch celebrations are made illegal under the Indian Act. 1880s–1996 The Indian Act is amended to give responsibility for the education of children to mostly church-run residential schools. The law required compulsory attendance for those status Indians under the age of 16 until they reached 18 years of age in Indian schools. There were 130 residential schools in Canada. Most residential schools ceased to operate by the mid-1970s; the last federally run residential school in Canada closed in 1996. 1885 As Chinese labourers are no longer needed to work on building the railways, the Chinese Immigration Act sets a head tax of $50 on every Chinese person entering Canada. 1890, March 18 The Manitoba legislature passes the Official Language Act to abolish the official status of the French language that is used in the Legislature, laws, records, journals and courts. This was in violation of the Manitoba Act of 1870 which declared English and French as official languages in Manitoba*. -

The Evacuation of the Japanese Canadians, 1942: a Realist Critique of the Received Version

The Evacuation of the Japanese Canadians, 1942: A Realist Critique of the Received Version J.L. Granatstein and Gregory A. Johnson The popularly accepted version of the evacuation of the Japanese Canadians from the Pacific Coast in 1941-1942 and the background to it runs roughly like this. The white population of British Columbia had long cherished resentments against the Asians who lived among them, and most particularly against the Japanese Canadians. Much of this sprang from envy of the Japanese Canadians' hard-work and industry, much at the substantial share held by Japanese Canadians of the fishing, market gardening and lumbering industry. Moreover, white British Columbians (and Canadians generally) had long had fears that the Japanese Canadians were unassimilable into Canadian society and, beginning early in this century and intensifying as the interwar period wore on, that many might secretly be acting as agents of their original homeland, now an aggressive and expansionist Japan. Liberal and Conservative politicians at the federal, provincial and municipal levels played upon the racist fears of the majority for their own political purposes. Thus when the Second World War began in September 1939, and when its early course ran disastrously against the Allies, there was already substantial fear about "aliens" in British Columbia (and elsewhere) and a desire to ensure that Japanese Canadians would be exempted from military training and service. The federal government concurred in this, despite the desire of many young Japanese Canadians to show their loyalty to Canada by enlisting. After 7 December 1941 and the beginning of the Pacific War, public and political pressures upon the Japanese Canadians increased exponentially. -

Italian Canadian Experiences During World War Ii

ITALIAN CANADIAN EXPERIENCES DURING WORLD WAR II he early population of Niagara Falls was largely of government unlimited powers to protect the state from any British origin, but from around the 1880s, this began internal or external threats, to ban subversive political T to change with a new influx of peoples of European organizations and to suspend foreign-language newspapers. It background. The construction boom that created railways, a also allowed for the internment of Canadian residents born in post office, fire hall, street car system, steam electric countries or empires at war with Canada. When Canada generating plant, water works and numerous churches formally declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939, attracted mainly Italian immigrants. Later on, with the turn-of around 850 German-Canadians were interned and over 66,000 -the-century hydro electric plants at the Falls, more Germans, German and Austrian Canadians (naturalized citizens) who had Hungarians, Ukrainians, Polish and others began to arrive as well. arrived in Canada after 1922, were forced to report to the police regularly. Later, when Italy entered the war on the side The growing close-knit Italian community opened of the Germans, the Canadian government gave the Royal new commercial establishments: groceries, barbershops, shoe Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) orders to arrest Italian repairs, etc., to meet their needs. They settled together, Canadians considered to be a security risk. Of the approximate largely according to their areas of origin, in neighbourhoods in 112,625 Italian-Canadian residents in Canada, 31,000 were Clifton, Drummondville and the Glenview area. The first Italian organization came in 1912 with the construction of St. -

Canadian Nikkei Institutions and Spaces

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ritsumeikan Research Repository ORIGINAL RESEARCH: Canadian nikkei institutions and spaces Lyle De Souza 1 1 Abstract Since their first arrival in Canada in 1877 to the present period, Canadian nikkei have established a variety of institutions and spaces that highlight their position within Canada as a minority group. Canadian nikkei history began with their labelling as “yellow peril”, followed by their internment during the Second World War, their dispersal after the Second World War, their award of Redress in 1988, and finally their place as a “model minority” in modern multicultural Canada. These main historical milestones have been reflected in various commemorative institutions and spaces such as Powell Street and Nikkei Place which function not just in a practical sense for gathering the Canadian nikkei together but also in an ideological sense to help shape their cultural identities extending transnationally across the Asia Pacific region. Keywords: Canada, Cultural identity, Institutions and spaces, Minorities, Multiculturalism, Nikkei. Introduction The ‘nikkei’ are people of Japanese descent living outside Japan and no longer Japanese citizens. Canadian nikkei can therefore be defined as Canadians of Japanese descent. Some argue, such as the Kaigai Nikkeijin Kyōkai (Association of Nikkei & Japanese Abroad), that the term nikkei includes all Japanese living outside of Japan even if they hold Japanese citizenship (Hamano 2008: 5). Canadian nikkei are also known as “Japanese(-)Canadians” (with or without the hyphen), although this label has been criticized by some for essentializing both sides of the hyphen and thus not accurately reflecting their identity (Mahtani 2002). -

Demographic Characteristics of Japanese Canadians in 2016 from 2016 Census of Population Takashi Ohki St. Albert, Alberta, Canad

Demographic Characteristics of Japanese Canadians in 2016 From 2016 Census of Population Takashi Ohki St. Albert, Alberta, Canada November 15, 2017 [email protected] 1. How many Japanese Canadians are there in Canada? · There are about 121,000 Japanese Canadians in Canada. · Japanese Canadians take up 0.35 percent of the total Canadian population. How big is the population of Japanese Canadians in Canada? The best source of information for this question is the Census of Population by Statistics Canada. The Census has been taken every five years and the latest Census was taken in 2016. In the Census, there has been a question regarding the ethnic origin of a respondent. The response to this question can be used to obtain statistics on the size of Japanese Canadians in Canada. A respondent was asked to select a single or multiple origins of his/her ancestors. Here, an ancestor was used to mean someone more distant than a grandparent and meant his/her ethnic or cultural root but did not mean the citizenship, language or place of birth of his/her ancestors. The choice of ethnic origin reflected a respondent’s perception of his/her ethnic ancestry. Thus, a person’s ethnic origin was not absolute or permanent. It could change as his or her social environment changed. Therefore, an ethnic origin in the Census was not an anthropological definition. Rather, it was a cultural definition. In this report, we call Canadians with a single Japanese ethnic origin and a Japanese ethnic origin as of one of multiple ethnic origins Japanese Canadians. -

Asian Heritage Month at the TDSB

Asian Heritage Month at the Toronto District School Board This slidedeck is the final product of an inquiry project undertaken by a teacher and a small group of students in response to our Asian Heritage Month theme: “Discover. Share. Celebrate our Resiliency!“ The work here represents just a few facets of the much larger, diverse, complex, historic Asian diaspora. Land Acknowledgement Asian people have arrived to the land now known as Canada in many waves over time, as undocumented, labourers, migrant workers, refugees and immigrants. When arriving in Canada, settlers, including Asian people, become part of Canada’s historic and ongoing project of colonialism. We have a responsibility to learn the histories of Indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands we now occupy, and to recognize the enduring presence of all First Nations, Métis and the Inuit peoples. We also recognize how Indigenous and Asian struggles are inextricably linked. We recognize the need for our communities to raise our voices in solidarity, share resources and take collective action for truth and reconciliation. Asian Heritage Month at the Toronto District School Board MAY 2021 Table of Contents 575% Introduction 1675% South Asia Why do we celebrate Asian Southeast Asia 675% Heritage Month? 1975% Notable Canadians of Who is of Asian descent? 7 22 Asian Heritage Central and Western 75% 75% Interactive Quiz 8 Asia 30 13 East Asia 31 Credits On December 6, 2001, the Senate of Canada adopted a motion introduced by the honourable Dr. Senator Poy to federally recognize the month of May as Asian Heritage Month. In May 2002, the Government of Canada signed an official declaration to designate May as Asian Heritage Month.