Paediatric Surgical Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Acute Abdominal Pain in Children

Clinical Acute Abdominal Pain in Children Urgent message: This article will guide you through the differential diagnosis, management and disposition of pediatric patients present- ing with acute abdominal pain. KAYLEENE E. PAGÁN CORREA, MD, FAAP Introduction y tummy hurts.” That is a simple statement that shows a common complaint from children who seek “M 1 care in an urgent care or emergency department. But the diagnosis in such patients can be challenging for a clinician because of the diverse etiologies. Acute abdominal pain is commonly caused by self-limiting con- ditions but also may herald serious medical or surgical emergencies, such as appendicitis. Making a timely diag- nosis is important to reduce the rate of complications but it can be challenging, particularly in infants and young children. Excellent history-taking skills accompanied by a careful, thorough physical exam are key to making the diagnosis or at least making a reasonable conclusion about a patient’s care.2 This article discusses the differential diagnosis for acute abdominal pain in children and offers guidance for initial evaluation and management of pediatric patients presenting with this complaint. © Getty Images Contrary to visceral pain, somatoparietal pain is well Pathophysiology localized, intense (sharp), and associated with one side Abdominal pain localization is confounded by the or the other because the nerves associated are numerous, nature of the pain receptors involved and may be clas- myelinated and transmit to a specific dorsal root ganglia. sified as visceral, somatoparietal, or referred pain. Vis- Somatoparietal pain receptors are principally located in ceral pain is not well localized because the afferent the parietal peritoneum, muscle and skin and usually nerves have fewer endings in the gut, are not myeli- respond to stretching, tearing or inflammation. -

Non-Traumatic Abdominal Emergency Imaging Hepatobiliary Emergency

บทความวชาการิ Non-Traumatic Abdominal Emergency Imaging Hepatobiliary Emergency จฬาลุ กษณั ์ พรหมศร ภาควิชารังสีวิทยา คณะแพทยศาสตร์ มหาวิทยาลัยขอนแก่น Non Traumatic Abdominal Emergency Imaging invasive amebiasis Hepatobiliary Emergency o Antibody to Entamoeba rising - Liver abscess o trophosoites ascend via portal vein then - Cholangitis invaded parenchyma - Acute cholecystitis o chocolate-colored, pasty material (anchovy - Gall stone ileus paste) - Mirizzi syndrome o single/multipe Periperheral near capsule Pancreatitis - Fungal liver abscess Appendicitis o Pts hematologic malignancy or compromised Small bowel obstruction o Microabcess involving liver, spleen and Peptic Ulcer perforation kidneys Mid gut volvulous o Leukemia/ most common Candia albicans Sigmoid volvulous o Other; Cryptococcus, histoplasmosis, Mesenteric vascular ischemia mucormycosis, Aspergillus Diverticulitis o Size 2-20 mm Imaging tools Acute abdomen series Imaging; Chest upright - Plain film; hepatomegaly, intrahepatic gas/an Abdomen upright fluid level Abdomen supine - US: Left lateral decubitus o variable in shape and echo (hypoechoic, Ultrasound hyperechoic, anechoic) with septation, fluid level CT without and with posterior enhancement MRI o Amebic; round/oval hypoechoic mass abuts liver capsule Liver abscess o Fungal; multiple tiny small echoic lesions - Pyogenic liver abscess scattered through liver parenchyma o(K pneumonia, E coli, Enterococcus, o US, CT 4 patterns of hepatosplenic Burkholderia, Streptococcus, and Staphylococcus spe- candidiasis cies) 1. wheel-within-a wheel; central hypoechic of o Solitary necrosis containing fungal, surrounded echogenic o Multiple inflammatory cells o Few mm- cm 2. Bull’s-eye of central echogenic nidus surrounded - Amebic liver abscess by hypoechoic rim( pts active fungal infection with nor- o Amebic liver abscess; E.Histolytica mal white cell) o most common extraintestinal from of 3. -

The Survey Film in Acute Abdominal Disorders

Gratitude is expressed to Dr. Price E. Thomas, determine some of factors controlling rate of action of curare. J. Physiol. 106:20P, 1947. Department of Physiology, Kirksville College of 10. Kalow, W.: Hydrolysis of local anesthetics by human serum Osteopathy and Surgery, for his guidance in the cholinesterase. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Therap. 104:122-134, Feb. 1952. writing of this paper, and to Mrs. Kathryn Balder- 11. Beecher, H. K., and Murphy, A. J.: Acidosis during thoracic son for preparation of the diagrams. surgery. J. Thoracic Surg. 19:50-70, Jan. 1950. 12. Lehmann, H., and Silk, E.: Succinylrnonocholine. Brit. M. J. 1:767-768, April 4, 1953. 13. Frumin, J. M.: Hepatic inactivation of succinylcholine in dog. Fed. Proc. 17:368, 1958. 1. Boba, A., et al.: Effects of apnea, endotracheal suction, and 14. Barnes, J. M., and Davies, D. R.: Blood cholinesterase levels oxygen insufflation, alone and in combination, upon arterial oxygen in workers exposed to organo-phosphorous insecticides. Brit. M. J. saturation in anesthetized patients. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 53:680-685, 2:816-819, Oct. 6, 1951. May 1959. 15. Lehmann, H., and Ryan, E.: Familial incidence of low pseudo- 2. Bard, P.: Medical physiology. Ed. 10. C. V. Mosby Co., St. cholinesterase level. Lancet 2:124, July 21, 1956. Louis, 1956. 16. Lehmann, H., and Simmons, P. H.: Sensitivity to suxame- 3. Ruch, T. C., and Fulton, J. F.: Medical physiology and bio- thonium; apnoea in two brothers. Lancet 2:981-982, Nov. 8, 1958. physics. Ed. 18. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1960. 17. -

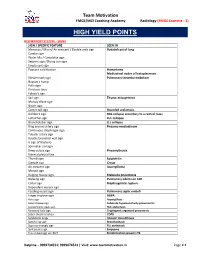

High Yield Points

Team Motivation FMGE/MCI Coaching Academy Radiology (FMGE Essentia - 3) HIGH YIELD POINTS RESPIRATORY SYSTEM – SIGNS SIGN / SPECIFIC FEATURE SEEN IN Meniscus / Moon/ Air crescent / Double arch sign Hydatid cyst of lung Cumbo sign Water lilly / Camalotte sign Serpent sign / Rising sun sign Empty cyst sign Popcorn calcification Hamartoma Mediastinal nodes of histoplasmosis Westermark sign Pulmonary thrombo-embolism Hapton’s hump Palla sign Fleishner lines Felson’s sign Sail sign Thymic enlargement Mulvay Wave sign Notch sign Comet tail sign Rounded atelectasis Golden S sign RUL collapse secondary to a central mass Luftsichel sign LUL collapse Broncholobar sign LLL collapse Ring around artery sign Pneumo-mediastinum Continuous diaphragm sign Tubular artery sign Double bronchial wall sign V sign of Naclerio Spinnaker sail sign Deep sulcus sign Pneumothorax Visceral pleural line Thumb sign Epiglottitis Steeple sign Croup Air crescent sign Aspergilloma Monod sign Bulging fissure sign Klebsiella pneumonia Batwing sign Pulmonary edema on CXR Collar sign Diaphragmatic rupture Dependant viscera sign Feeding vessel sign Pulmonary septic emboli Finger in glove sign ABPA Halo sign Aspergillosis Head cheese sign Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis Juxtaphrenic peak sign RUL atelectasis Reversed halo sign Cryptogenic organized pneumonia Saber sheath trachea COPD Sandstorm lungs Alveolar microlithiasis Signet ring sign Bronchiectasis Superior triangle sign RLL atelectasis Split pleura sign Empyema Tree in bud sign on HRCT Endobronchial spread in TB -

Common Surgical Concerns Dr. Metzgar

COMMON SURGICAL Martha Metzgar, DO, CONCERNS FAAFP SURGERY ON AOBFP EXAM ¡EENT – 5% - Just the first E ¡General Surgery – 3% - some ¡Orthopedics – 3% - NOPE A 45-year-old female has ultrasonography of her kidneys as part of an evaluation for uncontrolled hypertension. The report notes an incidental finding of stones in the gallbladder, confirmed on right upper quadrant ultrasonography. She has no CASE 1 symptoms you can relate to the gallstones. Other than hypertension she has no chronic medical problems. Which one of the following should you recommend to her at this time regarding the gallstones? A) Expectant management B) Oral dissolution therapy C) Extracorporeal lithotripsy D) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP) E) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy BILIARY CONDITIONS ¡Cholecystitis §inflammation and infection of the gallbladder caused by blockage of the cystic duct ¡Cholelithiasis – Cause Biliary colic §Transient obstruction of the cystic duct with gallstone. ¡Choledocholithiasis § stone in the common bile duct – often causes increases in LFTs ¡Cholangitis §Inflammation of the bile ducts CHOLELITHIASIS ¡ Risk factors ¡ Asymptomatic - Obesity § 10% will be symptomatic - Rapid/Cyclic weight loss in 5 years § Childbearing § 25% in 10 years § Female § Expectant management § First degree relative ¡ Oral dissolution therapy § Native American or not helpful Scandinavian descent ¡ Symptomatic – surgery § Drugs - Ceftriaxone, estrogen, TPN ¡ Imaging of choice is § Increasing age ultrasound. § Ileal disease, resection, or bypass -

Pediatric Appendicitis

Progressing Aspects in Pediatrics L UPINE PUBLISHERS and Neonatology Open Access DOI: 10.32474/PAPN.2017.01.000101 ISSN: 2637-4722 Review Article Pediatric Appendicitis Volkan Sarper Erikci* and Tunç Özdemir Department of Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University, Tepecik Training Hospital, Turkey Received: December 13, 2017; Published: December 20, 2017 *Corresponding author: Volkan Sarper Erikci MD, Associate Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Kazim Dirik Mah. Mustafa Kemal Cad. Hakkıbey apt. No:45 D.10 35100 Bornova-İzmir, Turkey Abstract Appendicitis is the most common surgical diagnosis for children who present with abdominal pain to the emergency department. However, there are nonspecific examination findings and variable historical features during its presentation. Diagnosis of appendicitis in the pediatric patient may be challenging for the clinician dealing with these patients. It is important to have a high index of suspicion and taking a detailed history and physical examination. In diagnosis of appendicitis, adjunctive studies that may be useful are the white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, urinalysis, ultrasonography and computerized tomography when necessary. When appendicitis is suspected, patients should receive immediate surgical consultation, as well as volume replacement and antibiotics if indicated. With this timely approach it will be possible to prevent the significant morbidity that is associated with delayed diagnoses in younger patients. Introduction Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children and adolescents. Although it is uncommon in preschool in 31% of cases, transverse appendix in the retrocecal recess in children, appendicitis may present at any age. The lifetime risk of 2.5% of cases, paracecal and preileal ascending appendix in 1% of cases. -

Guidelines for Surgical Emergencies The

GUIDELINES FOR SURGICAL EMERGENCIES Recommended by THE ASSOCIATION OF SURGEONS OF INDIA FOREWORD The Association of Surgeons of India founded in1938 is the second largest professional body of Surgeons in the world next to the American College of Surgeons. The role of ASI in India is unique compared to the position of similarly placed organizations in the rest of the world where such bodies have specific statutory role in academics, training, examination and credentialing. This has a negative impact in policy making as the data is grossly inadequate when the professional is kept away. The Association of Surgeons of India is making an earnest attempt to set in practice Guidelines for its members to aid them in their daily practice. This book comprises of Guidelines to address common emergencies confronted by Surgeons practicing in India. Each of the topics is written by one or more Consultants and had been peer reviewed by a Panel of experts to increase the credibility of its contents. Hope this will ensure a better and safe practice in India. We hope to present this the various statutory authorities in India so that this becomes the benchmark for reference in policy making, legal disputes and even part of the curriculum of training specialists. Dr Arvind Kumar Dr Sanjay Kumar Jain MBBS; MNAMS; FACS; FICS; FUICC; FIAGES MS; FAIS; FIACS; FIAGES PRESIDENT ASI 2019 HON.SECRETARY ASI 2019 Dr. B.C. Roy Awardee Chairman, Centre for Chest Surgery & Professor, Department of Surgery Director, Institute of Robotic Surgery Gandhi Medical College Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh Former: Professor of Surgery & Head, Thoracic & Robotic Unit, AIIMS, New Delhi, India Scientific Committee Dr Raghu Ram Dr Dilip S Gode MS; FRCS (Eng); FRCS (Edin); FRCS (Glasg); FRCS (Irel); FACS MBBS; MS; FICS; FMAS; PhD (MAS) VICE PRESIDENT ASI 2019 IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT ASI 2019 Padma Shri Awardee (2015) Former Vice Chancellor DMIMS Dr. -

Routine Abdominal X-Rays in the Emergency Department 381

Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 11/02/2017. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. Radiología. 2015;57(5):380---390 www.elsevier.es/rx UPDATE IN RADIOLOGY Routine abdominal X-rays in the emergency ଝ department: A thing of the past? a,∗ b c J.M. Artigas Martín , M. Martí de Gracia , C. Rodríguez Torres , c d D. Marquina Martínez , P. Parrilla Herranz a Radiología de Urgencias, Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain b Radiología de Urgencias, Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain c Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain d Servicio de Urgencias, Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain Received 2 January 2015; accepted 22 June 2015 KEYWORDS Abstract The large number of abdominal X-ray examinations done in the emergency depart- Abdomen; ment is striking considering the scant diagnostic yield of this imaging test in urgent disease. Most Plain films; of these examinations have normal or nonspecific findings, bringing into question the appropri- Emergencies; ateness of these examinations. Abdominal X-ray examinations are usually considered a routine Diagnosis; procedure or even a ‘‘defensive’’ screening tool, whose real usefulness is unknown. For more Indications; than 30 years, the scientific literature has been recommending a reduction in both the number Appropriateness of examinations and the number of projections obtained in each examination to reduce the dose of radiation, unnecessary inconvenience for patients, and costs. Radiologists and clinicians need to know the important limitations of abdominal X-rays in the diagnostic management of acute abdomen and restrict the use of this technique accordingly. -

Pediatric Surgery and Medicine for Hostile Environments

PEDIATRIC SURGERY AND MEDICINE FOR HOSTILE ENVIRONMENTS Kevin M. Creamer, MD • Michael M. Fuenfer, MD MY MEDI AR CA S L E D T E A P T A S R T D M E T E I N N T U B O E R T D TU EN INSTI Second Edition Pediatric Surgery and Medicine for Hostile Environments Second Edition Borden Institute US Army Medical Department Center and School Health Readiness Center of Excellence Fort Sam Houston, Texas Office of The Surgeon General United States Army Falls Church, Virginia i The test of the morality of a society is what it does for its children. —Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906–1945) ii This book is dedicated to the military medical professional in a land far from home, standing at the bedside of a critically ill child. iii Dosage Selection: The authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of dosages cited herein. However, it is the responsibility of every practitioner to consult appropriate information sources to ascertain correct dosages for each clinical situation, especially for new or unfamiliar drugs and procedures. The authors, editors, publisher, and the Department of Defense cannot be held responsible for any errors found in this book. Use of Trade or Brand Names: Use of trade or brand names in this publication is for illustrative purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Department of Defense. Neutral Language: Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the personal views of the authors and are not to be construed as doctrine of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. -

Internal-Medicine-EOR-Study-Guide

INTERNAL MEDICINE CARDIOVASCULAR Angina Pectoris • MOA: Insufficient oxygen supply to cardiac muscle, most commonly caused by atherosclerotic narrowing and less commonly by constriction of coronary arteries; CAD = MC cause • Stable angina: syndrome of precordial discomfort of pressure from transient myocardial ischemia à PREDICTABLE! o >70% stenosis; normal troponin/CK-MB; resting EKG normal; during episode >1mm ST depression +/- T wave o Diagnosis: § Symptoms § ECG: ST depression 1mm = positive test; inversion / flattening T waves; normal in 25% § myocardial imaging: exercise stress test (most useful / cost effective), echo, coronary angiography o Treatment: aspirin, nitrates, B-blockers, Ca channel blockers, ACE-I, statin, coronary angioplasty, CABG § B-blockers prolong life in patients with coronary disease and are first line therapy for chronic angina • Unstable: when pain is less responsive to NTG, lasts longer, occurs at rest / less exertion – ANY CHANGE à eval o Diagnosis: EKG = normal between attacks; stress test; angiography = gold (assess severity of coronary artery lesions when considering PCI or CABG) o Treatment: antiplatelets, B-blockers, NTG, CCB, revascularization, ACE-I, statins • Prinzmetal: transient coronary artery vasospasm within normal coronary anatomy or site of atherosclerotic plaque o Smoking = #1 RF!! o Diagnosis: ACS work up (CK, CK-MB, troponins – may be normal / EKG – may have transient STE); coronary angiography with injection of provoking agents into coronary artery = gold o Treatment: nitrates and CCB; -

Acute Renal Infarction Complicated by a Sentinel Loop in a Patient with Atrial Fibrillation

Case Report Page 1 of 5 Acute renal infarction complicated by a sentinel loop in a patient with atrial fibrillation Kiyoo Mori1, Kenshi Hayashi2, Kotaro Oe3, Toru Aburao2, Mariko Yagi1, Masakazu Yamagishi2 1Department of Internal Medicine, Houju Memorial Hospital, Nomi, Japan; 2Department of Cardiovascular and Internal Medicine, Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medicine, Kanazawa, Japan; 3Department of Internal Medicine, Saiseikai Kanazawa Hospital, Kanazawa, Japan Correspondence to: Kiyoo Mori, MD. Department of Internal Medicine, Houju Memorial Hospital, 11-71 Midorigaoka, Nomi City 923-1226, Japan. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: A sentinel loop observed on plain radiography is a known sign of localized paralytic ileus that is primarily associated with acute pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, and acute appendicitis. Here, we report a case of acute renal infarction (RI) complicated by a sentinel loop. A 58-year-old man with atrial fibrillation (AF) was hospitalized for paralytic ileus and was subsequently diagnosed with acute RI caused by embolism from the heart. Reports of sentinel loop signs on radiographs as a complication of acute RI are not available in previous English literature. For early diagnosis of acute RI and initiation of therapy to recover the function of the affected kidney and to prevent repeated thromboembolic events, it is important to recognize that a sentinel loop can be seen in acute RI as well as in other intra-abdominal inflammatory diseases. Keywords: Renal infarction (RI); sentinel loop; paralytic ileus; atrial fibrillation (AF) Received: 05 March 2017; Accepted: 23 March 2017; Published: 13 April 2017. doi: 10.21037/jxym.2017.03.14 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jxym.2017.03.14 Introduction Case presentation Acute renal infarction (RI) is rare and may even be an A 58-year-old man with a medical history of AF was admitted under-recognized disorder. -

Jebmh.Com Images in Clinical Medicine

Jebmh.com Images in Clinical Medicine GAS PATTERNS IN ACUTE ABDOMEN-REVISITED: A PICTORIAL ESSAY C. R. Srinivasa Babu1, Arjun Prakash2, Jatla Jyothi Swaroop3, Vishwa Premraj D. R4 1Professor & HOD, Department of Radio-diagnosis, PES Institute of Medical Sciences & Research. 2Assistant Professor, Department of Radio-diagnosis, PES Institute of Medical Sciences & Research. 3Post Graduate Student, Department of Radio-diagnosis, PES Institute of Medical Sciences & Research. 4Post Graduate student, Department of Radio-diagnosis, PES Institute of Medical Sciences & Research. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Acute abdomen is defined as the clinical condition in which the patient presents with acute severe abdominal symptoms within a period of 24 hours and where emergency medical or surgical intervention is required. A plain radiograph of the abdomen is often the first line of investigation in patients presenting with an acute abdomen, in spite of advances in other promising modalities like Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). It is important to be familiar with gas patterns to narrow down on the differential diagnoses and to make a correct diagnosis. Here we present a pictorial essay of the spectrum of gas patterns on plain radiograms. KEYWORDS Plain Radiogram, Gas Patterns, Acute Abdomen, Volvulus. HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: C. R. Srinivasa Babu, Arjun Prakash, Jatla Jyothi Swaroop, Vishwa Premraj D. R. “Gas Patterns In Acute Abdomen-Revisited: A Pictorial Essay”. Journal of Evidence based Medicine and Healthcare; Volume 2, Issue 54, December 07, 2015; Page: 8799-8805, DOI: 10.18410/jebmh/2015/1231 INTRODUCTION: Acute abdomen is a term frequently Normal Gas Pattern: When assessing an abdominal used to describe the acute abdominal pain in a subgroup of radiogram, the following should be noted: patients who are seriously ill and have abdominal tenderness a.