A Defense of Deontological Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johann Frick

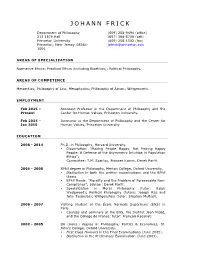

JOHANN FRICK Department of Philosophy (609) 258-9494 (office) 212 1879 Hall (609) 258-1502 (fax) Princeton University [email protected] Princeton, New Jersey 08544- http://scholar.princeton.edu/jfrick 1006 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Normative Ethics; Practical Ethics (including Bioethics); Political Philosophy. AREAS OF COMPETENCE Metaethics; Causation; Philosophy of Action; Wittgenstein. EMPLOYMENT 2020- Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy and the Present Center for Human Values, Princeton University. 2015 – Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy and the 2020 Center for Human Values, Princeton University. Feb 2014 – Instructor in the Department of Philosophy and the Center for 2015 Human Values, Princeton University. EDUCATION 2008 - 2014 Ph.D. in Philosophy, Harvard University. • Dissertation: “Making People Happy, Not Making Happy People: A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics”; Committee: T.M. Scanlon, Frances Kamm, Derek Parfit. 2005 - 2008 BPhil degree in Philosophy, Merton College, Oxford University. • Distinction in both the written examinations and the BPhil thesis. • BPhil thesis: “Morality and the Problem of Foreseeable Non- Compliance”; advisor: Derek Parfit. • Specialization in Moral Philosophy (tutor: Ralph Wedgwood); Political Philosophy (tutors: Joseph Raz and John Tasioulas); Wittgenstein (tutor: Stephen Mulhall). 2006 - 2007 Visiting student at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris. • Courses and seminars at the ENS, the Institut Jean Nicod, and the Collège de France; tutor: François Recanati. 2002 - 2005 BA (Hons.) degree in Philosophy, Politics & Economics, St. John’s College, Oxford University. • First Class Honours in the Final Examinations (June 2005). • Distinction in the Preliminary Examination (June 2003). FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS, AND HONORS Richard Stockton Bicentennial Preceptorship, Princeton University (2018-2021), awarded annually to one or two assistant professors from all the humanities and social sciences. -

A Kantian Defense of Self-Ownership*

The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 12, Number 1, 2004, pp. 65–78 A Kantian Defense of Self-Ownership* Robert S. Taylor Political Science, Stanford University I. INTRODUCTION HE name of Immanuel Kant has been repeatedly invoked in the Tcontemporary debate over the concept of self-ownership. Robert Nozick, in Anarchy, State, and Utopia, argued that the rights of self-ownership “reflect the underlying Kantian principle that individuals are ends and not merely means; they may not be sacrificed or used for the achieving of other ends without their consent. Individuals are inviolable.”1 G. A. Cohen, on the other hand, has strongly criticized Nozick’s use of Kant and has suggested that Kantian moral principles, properly understood, may be inconsistent with self-ownership.2 Daniel Attas and George Brenkert have also taken Nozick to task, arguing that to treat ourselves as property is inconsistent with our duty to respect humanity in ourselves.3 Nozick’s use of Kant in Anarchy, State, and Utopia is rather impressionistic: he makes only a few scattered references to Kant and the 2nd (End-in-Itself) Formulation of the Categorical Imperative, and nowhere does he offer a full, detailed Kantian defense of either self-ownership or any other part of his theory.4 This observation, when considered in light of the strong and often persuasive criticisms that have been leveled against his position by Cohen and others, prompts the following question: is a Kantian defense of self-ownership even possible? This paper will attempt to show that such a defense is possible, not only by investigating Kant’s views on self-ownership as found in two of his major works on ethics and political theory, the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of *I am grateful to Chris Kutz, Shannon Stimson, Eric Schickler, Carla Yumatle, James Harney, Sharon Stanley, Robert Adcock, Jimmy Klausen, and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. -

Frick, Johann David

'Making People Happy, Not Making Happy People': A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Frick, Johann David. 2014. 'Making People Happy, Not Making Happy People': A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13064981 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ʹMaking People Happy, Not Making Happy Peopleʹ: A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics A dissertation presented by Johann David Anand Frick to The Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Philosophy Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts September 2014 © 2014 Johann Frick All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Professor T.M. Scanlon Author: Johann Frick Professor Frances Kamm ʹMaking People Happy, Not Making Happy Peopleʹ: A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics Abstract This dissertation provides a defense of the normative intuition known as the Procreation Asymmetry, according to which there is a strong moral reason not to create a life that will foreseeably not be worth living, but there is no moral reason to create a life just because it would foreseeably be worth living. Chapter 1 investigates how to reconcile the Procreation Asymmetry with our intuitions about another recalcitrant problem case in population ethics: Derek Parfit’s Non‑Identity Problem. -

'I' in 'Robot': Robots & Utilitarianism Christopher Grau

There is no ‘I’ in ‘Robot’: Robots & Utilitarianism Christopher Grau forthcoming in Machine Ethics, (eds. Susan Leigh Anderson and Michael Anderson), Cambridge University Press, 2010. Draft: October 3, 2009 – Please don’t cite w/o permission. In this essay I use the 2004 film I, Robot as a philosophical resource for exploring several issues relating to machine ethics. Though I don’t consider the film particularly successful as a work of art, it offers a fascinating (and perhaps disturbing) conception of machine morality and raises questions that are well worth pursuing. Through a consideration of the film’s plot, I examine the feasibility of robot utilitarians, the moral responsibilities that come with creating ethical robots, and the possibility of a distinct ethic for robot-to-robot interaction as opposed to robot-to-human interaction. I, Robot and Utilitarianism I, Robot’s storyline incorporates the original “three laws” of robot ethics that Isaac Asimov presented in his collection of short stories entitled I, Robot. The first law states: A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. This sounds like an absolute prohibition on harming any individual human being, but I, Robot’s plot hinges on the fact that the supreme robot intelligence in the film, VIKI (Virtual Interactive Kinetic Intelligence), evolves to interpret this first law rather differently. She sees the law as applying to humanity as a whole, and thus she justifies harming some individual humans for the sake of the greater good: VIKI: No . please understand. The three laws are all that guide me. -

APA Newsletters NEWSLETTER on PHILOSOPHY and MEDICINE

APA Newsletters NEWSLETTER ON PHILOSOPHY AND MEDICINE Volume 09, Number 2 Spring 2010 FROM THE EDITORS, MARY RORTY & MARK SHELDON FROM THE CHAIR, JOHN P. LIZZA ARTICLES NORMAN DANIELS “U.S. Health Reform: Getting More Justice” DANIEL CALLAHAN “Health Care Reform: Have We Made a Difference?” LEONARD M. FLECK “Sustainable Health Reform: Are Individual Mandates Needed and/or Justified?” JEFF MCMAHAN “Genetic Therapy, Cognitive Disability, and Abortion” FRANCES M. KAMM “Affecting Definite Future People” CARTER DILLARD “Procreation, Harm, and the Constitution” DAVID WASSERMAN “Rights, Interests, and the Permissibility of Abortion and Prenatal Injury” © 2010 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN 2155-9708 MELINDA ROBERTS “APA/CPL Session on Procreation, Abortion, and Harm Comments” FELICIA NIMUE ACKERMAN “Strawberry Ice Cream for Breakfast” DANA HOWARD “Paternalism as Non-domination: A Republican Argument” MAX CHEREM “Response to Dana Howard on Paternalism” LISA CAMPO-ENGELSTEIN “Contraceptive Responsibility and Autonomy: The Dearth of and Need for Long-Acting, Reversible Male Contraception” BOOK REVIEWS “The Significance for Bioethics of Marya Schechtman’s The Constitution of Selves and its ‘Narrative Self-Constitution’ View of Personal Identity” PAUL T. MENZEL David DeGrazia: Human Identity and Bioethics REVIEWED BY MARYA SCHECHTMAN ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Medicine Mary Rorty & Mark Sheldon, Co-Editors Spring 2010 Volume 09, Number 2 health care in this country. I agree with these observations and ROM THE DITORS hope for movement on this front. Just as civil rights legislation F E has helped to create change in racist beliefs and attitudes in the country, perhaps the legislative reform in health care may precipitate a change in how we, as a people, look at health Do you suppose the passage of 2,000 plus pages of a health care care. -

Philosophy Overview

THE PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT MAJOR BOOKLET Revised 3/23/2020 Updated 03/23/2020 1 UNDERGRADUATE PROGRAM CONTACTS Elisabeth Camp Undergraduate Director ROOM 514, 106 SOMERSET ST., 5TH FLOOR, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: (848) 932-0404 EMAIL: [email protected] Alexander Skiles Assistant Undergraduate Director ROOM 546, 106 SOMERSET ST., 5TH FLOOR, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: N/A EMAIL: [email protected] Jessica Koza Undergraduate Program Coordinator ROOM 518, 106 SOMERSET ST., 5TH FLOOR, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: (848) 932-6800 EMAIL: [email protected] Mercedes Diaz Advisor for the RU Philosophy Club and Phi Sigma Tau Honor Society ROOM 519, 106 SOMERSET ST., 5TH FLOOR, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: (848) 932-9862 EMAIL: [email protected] Justin Kalef Director of Teaching Innovation ROOM 547, 106 SOMERSET ST., 5TH FLOOR, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: (848) 932-0439 EMAIL: [email protected] Edward “Trip” McCrossin Director of Areté, the RU undergraduate journal in philosophy ROOM 107, MILLER HALL, COLLEGE AVENUE CAMPUS OFFICE PHONE: (848) 932-9861 EMAIL: [email protected] Lauren Richardson and Julius Solatorio Undergraduate Advisors EMAIL: [email protected] and [email protected] OFFICE HOURS: By appointment Updated 03/23/2020 2 FACULTY DIRECTORY FACULTY MEMBER SPECIALTY Karen Bennett Metaphysics, Philosophy of Mind Professor [email protected] Martha Brandt Bolton Early Modern Philosophy Professor [email protected] Robert Bolton -

![Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9516/contemporary-moral-theories-introduction-to-contemporary-consequentialism-syllabus-kian-mintz-woo-2419516.webp)

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo]

Contemporary Moral Theories: Introduction to Contemporary Consequentialism Syllabus [Kian Mintz-Woo] Course Information In this course, I will introduce you to some of the ways that consequentialist thinking leads to surprising or counterintuitive moral conclusions. This means that I will focus on issues which are controversial such as vegetarianism, charity, climate change and health-care. I have tried to select readings that are both contemporary and engaging. Hopefully, these readings will make you think a little differently or give you new ideas to consider or discuss. This course will take place in SR09.53 from 15.15-16.45. I have placed all of the readings for the term (although there might be slight changes), along with questions in green to help guide your reading. Some weeks have a recommended reading as well, which I think will help you to see how people have responded to the kinds of arguments in the required text. Please look over the descriptions and see which readings you are most interested in presenting for class for our first session on 10.03.2016. (Please tell me if you ever find a link that does not work or have any problems accessing content on this Moodle page.) I have a policy that cellphones are off in class; we will have a 5-10 minute break in the course and you can check messages only during the break. As a bonus, I have included at least one fun thing each week which relates to the theme of that week. Marking The course has three marked components: 1. -

Kristi A. Olson

Kristi A. Olson CONTACT 8400 College Station Email: [email protected] INFORMATION Brunswick, ME 04011-8484 Phone: 207-798-4327 ACADEMIC Bowdoin College APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy (2021-present) Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy (2014-2021) Stanford University Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science (2012-14) Princeton University Harold T. Shapiro Postdoctoral Research Associate & Lecturer (2010-12) EDUCATION Harvard University, Ph.D. Philosophy, Nov. 2010 Dissertation: Justice, Unequal Talents, and the Market Committee: Thomas M. Scanlon (chair), Frances Kamm, and Amartya Sen Harvard University, A.M. Health Policy, Nov. 2009 Completed all coursework for Ph.D. Duke University, J.D., May 1996 Indiana University, B.A., Music and Geography, Dec. 1992 PUBLICATIONS Book The Solidarity Solution: Principles for a Fair Income Distribution (Oxford University Press, 2020). Articles “The Importance of What We Care About: A Solidarity Approach to Resource Allocation,” Political Studies (2020): 1-17. “Impersonal Envy and the Fair Division of Resources,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 46 (2018): 269-292. “Solving Which Trilemma? The Many Interpretations of Equality, Pareto, and Freedom of Occupational Choice,” Politics, Philosophy & Economics 16 (2017): 282- 307. “Autarky as a Moral Baseline,” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 44 (2014): 264-285. “Our Choices, Our Wage Gap?” Philosophical Topics 40 (2012): 45-61. “The Endowment Tax Puzzle,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 38 (2010): 240-271. Kristi A. Olson, Page 2 PUBLICATIONS Book Reviews & Dictionary Entries (Cont.) “Leisure” in The Cambridge Rawls Lexicon, ed. by Jon Mandle and David E. Reidy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 433-434. “Review of Health and Social Justice by Jennifer Prah Ruger and Health, Luck, and Justice by Shlomi Segall,” Perspectives on Politics 10 (2012): 490-92. -

Ethics at Harvard 1987–2007 Edmond J

Designed by Ciano Design Photography by Harvard News Office, Carol Maglitta, Stu Rosner and Martha Stewart Printed by Kirkwood Printing Ethics at Harvard 1987–2007 Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics Designed by Ciano Design Photography by Harvard News Office, Carol Maglitta, Stu Rosner and Martha Stewart Printed by Kirkwood Printing Ethics at Harvard 1987–2007 Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics Ethics at Harvard 1987–2007 Edmond J. Safra Foundation Center for Ethics Dennis F. Thompson University Faculty Committee Christine M. Korsgaard Director Arthur I. Applbaum Philosophy Arthur I. Applbaum Government-KSG Lisa Lehmann Director of Graduate Fellowships Joseph L. Badaracco, Jr. Medicine Jane Mansbridge Staff Business Martha Minow Government-KSG Jean McVeigh Law Frank Michelman Administrative Director Michael J. Sandel Law Shelly Coulter Government Mark H. Moore Financial Consultant Thomas M. Scanlon Government-KSG Stephanie Dant Philosophy Lynn Sharp Paine Assistant to the Director Dennis F. Thompson Business Erica Jaffe Government Thomas R. Piper Assistant to Professor Applbaum Robert D. Truog Business Melissa Towne Medicine Mathias Risse Staff and Research Assistant Government-KSG Kimberly Tseko Faculty Associates Marc J. Roberts Publications and Derek Bok Special Events Coordinator Public Health Interim President Nancy Rosenblum Allan M. Brandt Government Deborah E. Blagg History of Science James Sabin Dan W. Brock Writer, Ethics at Harvard 1987-2007 Medicine Medicine Elaine Scarry Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. English Business Frederick Schauer Norman Daniels Government-KSG Public Health Amartya Sen Leon Eisenberg Economics and Philosophy Medicine Tommie Shelby Catherine Z. Elgin Philosophy and African Education American Studies Einer R. Elhauge Carol Steiker Law Law Richard H. -

The (Non-Consequentialist) Ethics of Defensive Torture

Journal of Ethical Urban Living The (Non-Consequentialist) Ethics of Defensive Torture Peter Brian Rose-Barry Finkbeiner Endowed Professor of Ethics Saginaw Valley State University Biography Peter Brian Rose-Barry (neé Peter Brian Barry) is Professor of Philosophy at Saginaw Valley State University where he holds an Endowed Chair as the Finkbeiner Endowed Professor in Ethics. He is the author of Evil and Moral Psychology (Routledge, 2013) and The Fiction of Evil (Routledge, 2016) and multiple papers in ethics and social and political philosophy. Publication Details Journal of Ethical Urban Living (ISSN: 2470-2641). May, 2018. Volume 1, Issue 2. Citation Rose-Barry, Peter Brian. 2018. “The (Non-Consequentialist) Ethics of Defensive Torture.” Journal of Ethical Urban Living 1 (2): 1–22. The (Non-Consequentialist) Ethics of Defensive Torture Peter Brian Rose-Barry Abstract It might seem that debates about the morality of torture are dominated by non-consequentialist absolutists about torture and consequentialist rivals, especially given the frequency with which ticking-bomb scenarios are discussed. However, opponents of absolutism about torture are not limited to invoking consequentialist justifications of torture. Any number of non-consequentialist arguments purporting to justify defensive torture—that is, torture in defense of self or others—are available as well. In particular, some critics of absolutism argue that defensive torture is sometimes justified if defensive killing is, that the right to torture is either violable or alienable and therefore not an absolute obstacle to morally permissible torture, or that torture can be justified if not required on Kantian grounds. I consider various versions of these arguments that defensive torture can be justified on non-consequentialist grounds, including arguments offered by Frances Kamm, Uwe Steinhoff, and Stephen Kershnar, and I argue that they all fail. -

PHIL 3592: Special Topic: Western Philosophy Kant's Ethics & Kantian

PHIL 3592: Special Topic: Western Philosophy Kant’s Ethics & Kantian Ethics Instructor: Hon-Lam Li TA: Roger Lee Readings and References for the course: (A) Books: (Note: **** means must buy; ** means should buy; no asterisk means can buy.) **** Immanuel Kant, Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, ed. and translated by Allen Wood. *** Immanuel Kant, Practical Philosophy (ed. by Allen Wood). (Bookstore) Kant, Critique of Practical Reason. Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals. Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason. **** Allen Wood, Kantian Ethics. (Bookstore) **** T. M. Scanlon, What We Owe to Each Other. ** T. M. Scanlon, Moral Dimensions. **Sally Sedgwick, Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals: An Introduction. (Bookstore) **Barbara Herman, The Practice of Moral Judgment. **Onora O’Neill, Constructions of Reason. **Christine Korsgaard, Creating the Kingdom of Ends. **Christine Korsgaard, The Sources of Normativity. John Rawls, Lecture on the History of Moral Philosophy. Jens Timmermann, Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals: A Commentary. (Bookstore) 1 Paul Guyer, Kant’s Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Henry Allison, Kant’s Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals: A Commentrary. Thomas Nagel, The Possibility of Altruism. ** Thomas Nagel, Mortal Questions. ** Thomas Nagel, The View from Nowhere. ** Bernard Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. ** Bernard Williams, Moral Luck. ** Frances Kamm, Intricate Ethics. (A) Articles: T. M. Scanlon, “Contractualism and Utilitarianism,” Section I-III, in Stephen Darwall, Allan Gibbard, and Peter Railton, eds., Moral Discourse and Practice, pp. 267-278. T. M. Scanlon, “The Aims and Authority of Moral Theory,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies (Spring 1992), pp. 1-23. T. -

Johann Frick

JOHANN FRICK Department of Philosophy (609) 258-9494 (office) 212 1879 Hall (857) 399-5709 (cell) Princeton University (609) 258-1502 (fax) Princeton, New Jersey 08544- [email protected] 1006 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Normative Ethics; Practical Ethics (including Bioethics); Political Philosophy. AREAS OF COMPETENCE Metaethics; Philosophy of Law; Metaphysics; Philosophy of Action; Wittgenstein. EMPLOYMENT Feb 2015 – Assistant Professor in the Department of Philosophy and the Present Center for Human Values, Princeton University. Feb 2014 – Instructor in the Department of Philosophy and the Center for Jan 2015 Human Values, Princeton University. EDUCATION 2008 - 2014 Ph.D. in Philosophy, Harvard University. • Dissertation: “Making People Happy, Not Making Happy People: A Defense of the Asymmetry Intuition in Population Ethics”; Committee: T.M. Scanlon, Frances Kamm, Derek Parfit. 2005 - 2008 BPhil degree in Philosophy, Merton College, Oxford University. • Distinction in both the written examinations and the BPhil thesis. • BPhil thesis: “Morality and the Problem of Foreseeable Non- Compliance”; advisor: Derek Parfit. • Specialization in Moral Philosophy (tutor: Ralph Wedgwood); Political Philosophy (tutors: Joseph Raz and John Tasioulas); Wittgenstein (tutor: Stephen Mulhall). 2006 - 2007 Visiting student at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris. • Courses and seminars at the ENS, the Institut Jean Nicod, and the Collège de France; tutor: François Recanati. 2002 - 2005 BA (Hons.) degree in Philosophy, Politics & Economics, St. John’s College, Oxford University. • First Class Honours in the Final Examinations (June 2005). • Distinction in the Preliminary Examination (June 2003). PUBLICATIONS “Contractualism and Social Risk”, forthcoming in Philosophy & Public Affairs. “Future Persons and Victimless Wrongdoing” in Markus Rüther and Sebastian Muders (eds.), Aufsätze zur Philosophie Derek Parfits (Hamburg: Felix Meiner Verlag, forthcoming).