Dramatizing Lynching and Labor Protest: Case Studies Examining How Theatre Reflected Minority Unrest in the 1920S And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dealing with Jim Crow

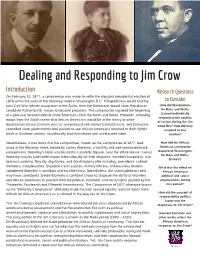

Dealing and Responding to Jim Crow Introduction Research Questions On February 26, 1877, a compromise was made to settle the disputed presidential election of 1876 within the walls of the Wormley Hotel in Washington D.C. If Republicans would end the to Consider post-Civil War military occupation of the South, then the Democrats would allow Republican How did Washington, candidate Rutherford B. Hayes to become president. The compromise signaled the beginning Du Bois, and Wells- of a post-war reconciliation of white Americans from the North and South. However, removing Barnett individually respond to the conflict troops from the South meant that African Americans would be at the mercy of white of racism during the Jim Southerners (many of whom were or sympathized with former Confederates), and Democrat- Crow Era? How did they controlled state governments who wanted to see African Americans returned to their rightful respond to one place in Southern society, as politically disenfranchised and uneducated labor. another? Nevertheless, it was ironic that the compromise, known as the Compromise of 1877, took How did the African place at the Wormley Hotel, owned by James Wormley, a wealthy and well-connected black American community entrepreneur. Wormley’s Hotel was located in Layafette Square, near the White House. James respond to Washington, Du Bois and Wells- Wormley and his hotel were known internationally for their elegance, excellent hospitality, and Barnett? delicious catering. Royalty, dignitaries, and Washington’s elite including: presidents, cabinet members, Congressmen, Supreme Court justices, military officers, and business leaders What was the effect on considered Wormley a confidant and excellent host. -

Notable Alphas Fraternity Mission Statement

ALPHA PHI ALPHA NOTABLE ALPHAS FRATERNITY MISSION STATEMENT ALPHA PHI ALPHA FRATERNITY DEVELOPS LEADERS, PROMOTES BROTHERHOOD AND ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE, WHILE PROVIDING SERVICE AND ADVOCACY FOR OUR COMMUNITIES. FRATERNITY VISION STATEMENT The objectives of this Fraternity shall be: to stimulate the ambition of its members; to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the causes of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual; to encourage the highest and noblest form of manhood; and to aid down-trodden humanity in its efforts to achieve higher social, economic and intellectual status. The first two objectives- (1) to stimulate the ambition of its members and (2) to prepare them for the greatest usefulness in the cause of humanity, freedom, and dignity of the individual-serve as the basis for the establishment of Alpha University. Table Of Contents Table of Contents THE JEWELS . .5 ACADEMIA/EDUCATORS . .6 PROFESSORS & RESEARCHERS. .8 RHODES SCHOLARS . .9 ENTERTAINMENT . 11 MUSIC . 11 FILM, TELEVISION, & THEATER . 12 GOVERNMENT/LAW/PUBLIC POLICY . 13 VICE PRESIDENTS/SUPREME COURT . 13 CABINET & CABINET LEVEL RANKS . 13 MEMBERS OF CONGRESS . 14 GOVERNORS & LT. GOVERNORS . 16 AMBASSADORS . 16 MAYORS . 17 JUDGES/LAWYERS . 19 U.S. POLITICAL & LEGAL FIGURES . 20 OFFICIALS OUTSIDE THE U.S. 21 JOURNALISM/MEDIA . 21 LITERATURE . .22 MILITARY SERVICE . 23 RELIGION . .23 SCIENCE . .24 SERVICE/SOCIAL REFORM . 25 SPORTS . .27 OLYMPICS . .27 BASKETBALL . .28 AMERICAN FOOTBALL . 29 OTHER ATHLETICS . 32 OTHER ALPHAS . .32 NOTABLE ALPHAS 3 4 ALPHA PHI ALPHA ADVISOR HANDBOOK THE FOUNDERS THE SEVEN JEWELS NAME CHAPTER NOTABILITY THE JEWELS Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; 6th Henry A. Callis Alpha General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Co-founder of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity; Charles H. -

'They Made Gullah': Modernist Primitivists and The

“ ‘They Made Gullah’: Modernist Primitivists and the Discovery and Creation of Sapelo Island, Georgia’s Gullah Community, 1915-1991” By Melissa L. Cooper A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Dr. Mia Bay and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2012 2012 Melissa L. Cooper ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “ ‘They Made Gullah’: Modernist Primitivists and the Discovery and Creation of Sapelo Island, Georgia’s Gullah Community, 1915-1991” by Melissa L. Cooper Dissertation Director: Dr. Mia Bay ABSTRACT: The history of Sapelo Islanders in published works reveals a complex cast of characters, each one working through ideas about racial distinction and inheritance; African culture and spirituality; and the legacy of slavery during the most turbulent years in America’s race-making history. Feuding social scientists, adventure seeking journalists, amateur folklorists, and other writers, initiated and shaped the perception of Sapelo Islanders’ distinct connection to Africa during the 1920s and 1930s, and labeled them “Gullah.” These researchers characterized the “Gullah,” as being uniquely connected to their African past, and as a population among whom African “survivals” were readily observable. This dissertation argues that the popular view of Sapelo Islanders’ “uniqueness” was the product of changing formulations about race and racial distinction in America. Consequently, the “discovery” of Sapelo Island’s Gullah folk was more a sign of times than an anthropological discovery. This dissertation interrogates the intellectual motives of the researchers and writers who have explored Sapelo Islanders in their works, and argues that the advent of American Modernism, the development of new social scientific theories and popular cultural works during the 1920s and 1930s, and other trends shaped their depictions. -

Medical Racism's Poison

Kenny racism 2016.06.19 Page 1 of 44 Medical Racism’s Poison Pen: The Toxic World of Dr. Henry Ramsay Stephen C. Kenny Unlike many of his physician tutors and student peers, Henry Ramsay, who was a graduate of the Medical College of Georgia, did not manage to defend his white racial capital and status as a slaveholder by serving in the Confederacy. In fact, Ramsay did not even live long enough to see Georgia’s ordinance of secession passed in Milledgeville in January 1861. As the American Medical Gazette commented in a brief obituary notice, “the wayward history of this eccentric and unfortunate man” instead saw a “melancholy termination.” Suggesting widespread public curiosity as to his fate, on September 12, 1856, the Lowell Daily Citizen and News reported that Henry Ramsay had “poisoned himself in his cell, by mixing seeds of the Jamestown weed in a cup of coffee.” With a promise to return to some of Ramsay’s troubling personal foibles, this essay concentrates on medical racism, as seen through the decidedly ordinary and representative career of this slaveholding Southern “country doctor.” John Hoberman, in Black and Blue, a comprehensive survey and analysis of mainstream medicine’s incorporation, development and dissemination of white racial prejudices in the twentieth century, defined the problem as stemming from a fundamental belief of Western racism: “that blacks and whites are opposite racial types, and . that black human beings are less complex organisms than white human beings.” In tandem, these deep-seated racial notions underpinned the fabrication of “a racially differentiated human biology that has suffused the tissues, fluids, bones, nerves, and organ systems of the human body with Kenny racism 2016.06.19 Page 2 of 44 racial meanings” which had a profound effect on medical thought and practice (Hoberman 66). -

The German Influence on the Life and Thought of W.E.B. Dubois. Michaela C

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2001 The German influence on the life and thought of W.E.B. DuBois. Michaela C. Orizu University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Orizu, Michaela C., "The German influence on the life and thought of W.E.B. DuBois." (2001). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2566. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2566 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON THE LIFE AND THOUGHT OF W. E. B. DU BOIS A Thesis Presented by MICHAELA C. ORIZU Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 2001 Political Science THE GERMAN INFLUENCE ON THE LIE AND THOUGHT OF W. E. B. DU BOIS A Master’s Thesis Presented by MICHAELA C. ORIZU Approved as to style and content by; Dean Robinson, Chair t William Strickland, Member / Jerome Mileur, Member ad. Department of Political Science ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I like would to thank my advisors William Strickland and Dean Robinson for their guidance, insight and patient support during this project as well as for the inspiring classes they offered. Many thanks also to Prof. Jerome Mileur for taking interest in my work and joining my thesis committee at such short notice. -

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmuel Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv

The National Left (First Draft) by Shmu'el Hasfari and Eldad Yaniv Open Source Center OSC Summary: A self-published book by Israeli playwright Shmu'el Hasfari and political activist Eldad Yaniv entitled "The National Left (First Draft)" bemoans the death of Israel's political left. http://www.fas.org/irp/dni/osc/israel-left.pdf Statement by the Authors The contents of this publication are the responsibility of the authors, who also personally bore the modest printing costs. Any part of the material in this book may be photocopied and recorded. It is recommended that it should be kept in a data-storage system, transmitted, or recorded in any form or by any electronic, optical, mechanical means, or otherwise. Any form of commercial use of the material in this book is permitted without the explicit written permission of the authors. 1. The Left The Left died the day the Six-Day War ended. With the dawn of the Israeli empire, the Left's sun sank and the Small [pun on Smol, the Hebrew word for Left] was born. The Small is a mark of Cain, a disparaging term for a collaborator, a lover of Arabs, a hater of Israel, a Jew who turns against his own people, not a patriot. The Small-ists eat pork on Yom Kippur, gobble shrimps during the week, drink espresso whenever possible, and are homos, kapos, artsy-fartsy snobs, and what not. Until 1967, the Left actually managed some impressive deeds -- it took control of the land, ploughed, sowed, harvested, founded the state, built the army, built its industry from scratch, fought Arabs, settled the land, built the nuclear reactor, brought millions of Jews here and absorbed them, and set up kibbutzim, moshavim, and agriculture. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Montgomery Aviation: a Rising Hoosier Star Grand Rapids, Michigan Texas Jet, Inc

2nd Quarter 2010 MMontgomeryontgomery AAviationviation A RRisingising HHoosieroosier SStartar Also Inside • IIndustryndustry AuditAudit Standards:Standards: FFactact oorr FFiction?iction? • TThehe EEU’sU’s SSchemecheme ttoo RReduceeduce CCarbonarbon EEmissionsmissions • BBuildinguilding CommunityCommunity andand AirportAirport RRelations:elations: IIdeasdeas YouYou CanCan ImplementImplement Permit No. 1400 No. Permit Silver Spring, MD Spring, Silver PAID U.S. Postage Postage U.S. Standard PRESORT PRESORT 1307*%*/('6&-"/%4&37*$&4505)&(-0#"-"7*"5*0/*/%6453: $POUSBDU'VFMt1JMPU*ODFOUJWF1SPHSBNTt'VFM2VBMJUZ"TTVSBODFt3FGVFMJOH&RVJQNFOUt"WJBUJPO*OTVSBODFt'VFM4UPSBHF4ZTUFNT tXXXBWGVFMDPNtGBDFCPPLDPNBWGVFMtUXJUUFSDPN"7'6&-UXFFUFS 2nd Quarter 2010 Aviation ISSUE 2 | VOLUME 8 Business Journal Offi cial Publication of the National Air Transportation Association Chairman of the Board President Kurt F. Sutterer James K. Coyne Midcoast Aviation, Inc. NATA Cahokia, Illinois Alexandria, Virginia Vice Chairman Treasurer James Miller Bruce Van Allen Flight Options BBA Aviation Flight Support Cleveland, Ohio The EU’s Scheme to Reduce Carbon Emissions Orlando, Florida By Michael France 22 Immediate Past Chairman This year marks the beginning of aviation’s inclusion into the Dennis Keith European Union’s Emission Trading Scheme, which is basically Jet Solutions LLC Europe’s version of a market-based approach to the reduction of Richardson, Texas greenhouse gas emissions. U.S.-based aircraft operators who fl y into, Board of Directors out of, or between EU airports will be affected. Charles Cox Chairman Emeritus Northern Air Inc. Reed Pigman Montgomery Aviation: A Rising Hoosier Star Grand Rapids, Michigan Texas Jet, Inc. By Paul Seidenman and David J. Spanovich 25 Fort Worth, Texas When Andi and Dan Montgomery took the plunge into the FBO Todd Duncan business at Indianapolis Executive Airport (TYQ) in 2000, it was Duncan Aviation Ann Pollard an especially risky business given that neither had any prior FBO Lincoln, Nebraska Shoreline Aviation experience. -

Application of Critical Race Feminism to the Anti-Lynching Movement: Black Women's Fight Against Race and Gender Ideology, 1892-1920

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title The Application of Critical Race Feminism to the Anti-Lynching Movement: Black Women's Fight against Race and Gender Ideology, 1892-1920 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kc308xf Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 3(0) Author Barnard, Amii Larkin Publication Date 1993 DOI 10.5070/L331017574 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE THE APPLICATION OF CRITICAL RACE FEMINISM TO THE ANTI-LYNCHING MOVEMENT: BLACK WOMEN'S FIGHT AGAINST RACE AND GENDER IDEOLOGY, 1892-1920 Amii Larkin Barnard* INTRODUCTION One muffled strain in the Silent South, a jarring chord and a vague and uncomprehended cadenza has been and still is the Ne- gro. And of that muffled chord, the one mute and voiceless note has been the sadly expectant Black Woman.... [Als our Cauca- sian barristersare not to blame if they cannot quite put themselves in the dark man's place, neither should the dark man be wholly expected fully and adequately to reproduce the exact Voice of the Black Woman. I At the turn of the twentieth century, two intersecting ideolo- gies controlled the consciousness of Americans: White Supremacy and True Womanhood. 2 These cultural beliefs prescribed roles for people according to their race and gender, establishing expectations for "proper" conduct. Together, these beliefs created a climate for * J.D. 1992 Georgetown University Law Center; B.A. 1989 Tufts University. The author is currently an associate at Bowles & Verna in Walnut Creek, California. The author would like to thank Professor Wendy Williams and Professor Anthony E. -

British Identity and the German Other William F

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 British identity and the German other William F. Bertolette Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bertolette, William F., "British identity and the German other" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2726. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2726 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BRITISH IDENTITY AND THE GERMAN OTHER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by William F. Bertolette B.A., California State University at Hayward, 1975 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2004 May 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the LSU History Department for supporting the completion of this work. I also wish to express my gratitude for the instructive guidance of my thesis committee: Drs. David F. Lindenfeld, Victor L. Stater and Meredith Veldman. Dr. Veldman deserves a special thanks for her editorial insights -

Lynching, Violence, Beauty, and the Paradox of Feminist History

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2000 Crossing the River of Blood Between Us: Lynching, Violence, Beauty, and the Paradox of Feminist History Emma Coleman Jordan Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/101 3 J. Gender Race & Just. 545-580 (2000) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons GEORGETOWN LAW Faculty Publications January 2010 Crossing the River of Blood Between Us: Lynching, Violence, Beauty, and the Paradox of Feminist History 3 J. Gender Race & Just. 545-580 (2000) Emma Coleman Jordan Professor of Law Georgetown University Law Center [email protected] This paper can be downloaded without charge from: Scholarly Commons: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/101/ Posted with permission of the author Crossing the River of Blood Between Us: Lynching, Violence, Beauty, and the Paradox of Feminist History Emma Coleman Jordan* I. AN INTRODUCTION TO LYNCHING: FIRST THE STORIES, THEN THE PICTURES A. Family Ties to Violent Racial Etiquette B. Finding Barbaric Photographs in the National Family Album II. CROSSING THE RACIAL DIVIDE IN FEMINIST HISTORY A. The Racial Strategies of Early Feminists B. The Paradox ofSubordination m. A CONTESTED HISTORY: AGREEING TO DISAGREE A. The Racial Contradictions of Jesse Daniels Ames, Anti-Lynching Crusader B. Can a Victim Be a Victimizer? IV. -

Nl261-1:Layout 1.Qxd

Volume 26 Kurt Weill Number 1 Newsletter Spring 2008 LOST IN THE STARS Volume 26 Kurt Weill Number 1 Newsletter In this issue Spring 2008 Note from the Editor 3 ISSN 0899-6407 Feature: Lost in the Stars © 2008 Kurt Weill Foundation for Music 7 East 20th Street The Story of the Song 4 New York, NY 10003-1106 Genesis, First Production, and Tour 6 tel. (212) 505-5240 fax (212) 353-9663 The Eleanor Roosevelt Album 10 Later Life 12 Published twice a year, the Kurt Weill Newsletter features articles and reviews (books, performances, recordings) that center on Kurt Books Weill but take a broader look at issues of twentieth-century music and theater. With a print run of 5,000 copies, the Newsletter is dis- Handbuch des Musicals: tributed worldwide. Subscriptions are free. The editor welcomes Die wichtigsten Titel von A bis Z 13 the submission of articles, reviews, and news items for inclusion in by Thomas Siedhoff future issues. Gisela Maria Schubert A variety of opinions are expressed in the Newsletter; they do not The Rest Is Noise: necessarily represent the publisher's official viewpoint. Letters to Listening to the Twentieth Century 14 the editor are welcome. by Alex Ross Joy H. Calico Staff Elmar Juchem, Editor Carolyn Weber, Associate Editor Artists in Exile: How Refugees from Twentieth-Century War and Dave Stein, Associate Editor Brady Sansone, Production Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts 15 by Joseph Horowitz Kurt Weill Foundation Trustees Jack Sullivan Kim Kowalke, President Joanne Hubbard Cossa Performances Milton Coleman, Vice-President Paul Epstein Der Silbersee in Berlin 17 Guy Stern, Secretary Susan Feder Tobias Robert Klein Philip Getter, Treasurer Walter Hinderer Welz Kauffman Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny in Mainz 18 Robert Gonzales Julius Rudel Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny in Essen 19 David Drew and Teresa Stratas, Honorary Trustees Robert Gonzales Harold Prince, Trustee Emeritus Lady in the Dark in Oullins 20 William V.