THE EASTERN ORTHODOX No 136: June 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edith Cavell Centenary Month October 2015

YOUR FREE GUIDE TO CENTENARY EVENTS EDITH CAVELL CENTENARY MONTH OCTOBER 2015 Find out more about the courageous First World War nurse who cared for injured soldiers in Brussels, whatever their nationality. Her part in helping allied soldiers to escape from German occupied Belgium led to her execution, at dawn on 12th October 1915. In association with Edith Cavell learned the fluent French which led to her post in Brussels as a pupil teacher at Laurel Court School in Peterborough Peterborough Cathedral Precincts. MusPeeumterborough Museum n TOURS n WORSHIP n TALKS n FAMILY ACTIVITIES n MUSIC n FASHION n ART SATURDAY 10TH OCTOBER FRIDAY 9TH OCTOBER & SUNDAY 11TH OCTOBER Edith Cavell Cavell, Carbolic and A talk by Diana Chloroform Souhami At Peterborough Museum, 7.30pm at Peterborough Priestgate, PE1 1LF Cathedral Tours half hourly, Diana Souhami’s 10.00am – 4.00pm (lasts around 50 minutes) biography of Edith This theatrical tour with costumed re-enactors Cavell was described vividly shows how wounded men were treated by The Sunday Times during the Great War. With the service book for as “meticulously a named soldier in hand you will be sent to “the researched and trenches” before being “wounded” and taken to sympathetic”. She the casualty clearing station, the field hospital, will re-tell the story of Edith Cavell’s life: her then back to England for an operation. In the childhood in a Norfolk rectory, her career in recovery area you will learn the fate of your nursing and her role in the Belgian resistance serviceman. You will also meet “Edith Cavell” and movement which led to her execution. -

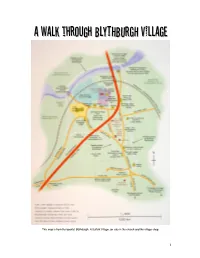

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks Cleveland Way Trail: walk the 3 miles from Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire to Helmsley Castle and tread in the footsteps of medieval Pilgrims along what’s now part of the Cleveland Way Trail. Camino de Santiago/Way of St James, Spain: along with trips to the Holy Land and Rome, this is the most famous medieval pilgrimage trail of all, and the most well-travelled in medieval times, at least until the advent of Black Death. Its destination point is the spot St James is said to have been buried, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Today Santiago is one of UNESCO’s World Heritage sites. Read more . the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela holds a Pilgrims’ Mass every day at noon. Walk as much or as little of it as you like. Follow the famous scallop shell symbols. A popular starting point, both today and in the Middle Ages, is either Le Puy in the Massif Central, France OR the famous medieval Abbey at Cluny, near Paris. The Spanish start is from the Pyrenees, on to Roncevalles or Jaca. These routes also take in the Via Regia and/or the Camino Frances. The Portuguese way is also popular: from the Cathedrals in either Lisbon or Porto and then crossing into Falicia/Valenca. At the end of the walk you receive a stamped certifi cate, the Compostela. To achieve this you must have walked at least 100km or cycled for 200. To walk the entire route may take months. Read more . The route has inspired many TV and fi lm productions, such as Simon Reeve’s BBC2 ‘Pilgrimage’ series (2013) and The Way (2010), written and directed by Emilio Estevez, about a father completing the pilgrimage in memory of his son who died along the Way of St James. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

General Index

_......'.-r INDEX (a. : anchorite, anchorage; h. : hermit, hermitage)' t-:lg' Annors,enclose anchorites, 9r-4r,4r-3. - Ancren'Riwle,73, 7-1,^85,-?9-8-' I t2o-4t r3o-r' 136-8, Ae;*,;. of Gloucest"i, to3.- | rog' rro' rr4t r42, r77' - h. of Pontefract, 69-7o. I ^ -r4o, - z. Cressevill. I AnderseY,-h',16' (Glos), h', z8' earian IV, Pope, 23. i eriland 64,88' rrz' 165' Aelred of Rievaulx, St. 372., 97, r34; I Armyq Armitdge, 48, Rule of, 8o, 85, 96-7,- :.o3, tog, tzz,l - 184--6,.rgo-l' iii, tz6, .q;g:' a', 8t' ^ lArthu,r,.Bdmund,r44' e"rti"l1 df W6isinghaffi,24, n8-g. I Arundel, /'t - n. bf Farne,r33.- I .- ':.Ye"tbourne' z!-Jt ch' rx' a"fwi", tt. of Far"tli, 5, r29. I Asceticism,2, 4'7r 39t 4o' habergeon' rr8---zr A.tfr.it"fa, Oedituati, h.'3, +, :'67'8. I th, x-'16o, r78; ; Sh;p-h"'d,V"'t-;:"i"t-*^--- r18'r2o-r' 1eni,.,i. [ ]T"]:*'ll:16o, 1?ti;ll'z' Food' ei'i?uy,- ;::-{;;-;h,-' 176,a. Margaret1 . '?n, ^163, of (i.t 6y. AshPrington,89' I (B^ridgnotjh)1,1:: '^'-'Cfii"ft.*,Aldrin$;--(Susse*),Aldrington (Sussex), -s;. rector of,oI, a. atal Ilrrf,nera,fsslurr etnitatatton tD_rru6rrur\rrrt,.-.t 36' " IAttendants,z' companig?thi,p' efa*i"l n. of Malvern,zo. I erratey,Katherine, b. of LedbutY,74-5, tql' Alfred, King, 16, r48, 168. | . gil*i"", Fia"isiead,zr, I Augustine,St', 146-7' Alice, a. of".6r Hereford, TT:-!3-7. -

A HISTORY of OUR CHURCH Welcome To

A HISTORY OF OUR CHURCH Welcome to our beautiful little church, named after St Botolph*, the 7th century patron saint of wayfarers who founded many churches in the East of England. The present church on this site was built in 1263 in the Early English style. This was at the request and expense of Sir William de Thorpe, whose family later built Longthorpe Tower. At first a chapel in the parish of St John it was consecrated as a church in 1850. The church has been well used and much loved for over 750 years. It is noted for its stone, brass and stained glass memorials to men killed in World War One, to members of the St John and Strong families of Thorpe Hall and to faithful members of the congregation. Below you will find: A.) A walk round tour with a plan and descriptions of items in the nave and chancel (* means there is more about this person or place in the second half of this history.) The nave and chancel have been divided into twelve sections corresponding to the numbers on the map. 1) The Children’s Corner 2) The organ area 3) The northwest window area 4) The North Aisle 5) The Horrell Window 6) The Chancel, north side 7) The Sanctuary Area 8) The Altar Rail 9) The Chancel, south side 10) The Gaskell brass plaques 11) Memorials to the Thorpe Hall families 12) The memorial book and board; the font B) The history of St Botolph, this church and families connected to it 1) St Botolph 2) The de Thorpe Family, the church and Longthorpe Tower 3) History of the church 4) The Thorpe Hall connection: the St Johns and Strongs 5) Father O-Reilly; the Oxford Movement A WALK ROUND THE CHURCH This guide takes you round the church in a clockwise direction. -

Issue 18 • Spring 2014 Patron: the Duchess of Kent Singing Out!

NEWS FROM THE CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION The benefits of a Choir School education ISSUE 18 • SPRING 2014 PATRON: THE DUCHESS OF KENT SINGING OUT! l Canterbury Cathedral Girls’ Choir sang their first Evensong on Saturday 25 January which included music by Vaughan Williams, Dyson and SS Wesley. As the girls processed out from the Quire stalls they received a standing ovation. Under the baton of Assistant Organist, David COnHAIRMAN 22 November moreR thanOGER 100,000O youngVEREND people worldwide, WRITES including… Newsholme, the girls will initially sing at many of our choristers, sang the music of Benjamin Britten. They were services when the boy choristers are on celebrating the centenary of the birth of one of the greatest composers of their twice-termly breaks. Their next the 20th century. Evensong is on Saturday 29 March, followed by the Diocesan Service Our cathedrals and college chapels taken for granted and that they are fully celebrating the 20th anniversary of continued to ring with the sound of supported, musically, socially and Women’s Ministry on Saturday 10 May. glorious music sung by our choristers financially. Music of a high quality often The sixteen girls are aged 12-16 and attend through Christmas, with much of it brought comes at a price, but I believe that any eight different schools in the area. to the fore through radio and television. money spent on cathedral music pays for This term we are working towards Easter itself many times over. It gives pleasure to permeates each day and where what they and I asked Christopher Walji, Head the listener, engaging many entering our do is highly-respected by fellow non- Chorister of Rochester Cathedral, to reflect cathedrals and college chapels for the first chorister pupils. -

Peterborough Local List Project Toolbox

Peterborough Local List Project Toolbox 1 Contents What is the Local List Project, page 3 What is a Heritage Asset, page 4 Locally Listed Heritage Assets, page 5 What is a Local List, page 6 What is the purpose of a Local Heritage List, page 6 Protection of Locally Listed Assets, page 7 Local List Selection Criteria, page 8 Explanation of the Local Listing process, page 10 Guide to submitting a Local List nomination, page12 2 What is the Local List Project? As part of the governments #buildbackbetter initiative, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government in association with Historic England, provided £1.5m to 22 areas to develop their Local Lists. Peterborough was successful in its bid and has received £38,000. These 22 areas, which also includes the neighbouring Cambridgeshire and Lincolnshire are test pilots in investigating different ways in which Local Lists can be developed and improved upon. The two main strands of Peterborough’s bid were its record of being at the forefront of the development of Local Lists and its proposed innovation with regard its digital submission. Peterborough was one on the first adopters of the Local List, and has been periodically adding new entries since its first adoption in 2012. Although the adopted heritage assets are concentrated in and around the city centre, the ratio of Locally Listed builds to statutorily Listed buildings of 30% is of a higher magnitude than the majority of other Local List’, demonstrating its extent. This percentage is simply a good baseline for which the project aims to substantially improve. -

Millstones for Medieval Manors

Millstones for Medieval Manors By DAVID L FARMER Abstract Demesne mills in medieval England obtained their millstones from many sources on the continent, in Wales, and in England. The most prized were French stones, usually fetched by cart from Southampton or ferried by river from London. Transport costs were low. Millstone prices generally doubled between the early thirteenth century and the Black Death, and doubled again in the later fourteenth century. With milling less profitable, many mills in the fourteenth century changed from French stones to the cheaper Welsh and Peak District stones, which Thames valley manors were able to buy in a large number of Midland towns and villages. Some successful south coast mills continued to buy French stones even in the fifteenth century. ICHARD Holt recently reminded us millstones were bought in a port or other that mills were at the forefront of town; demesne mills bought relatively R medieval technology and argued few at quarries. The most prized stones persuasively that windmills may have been came from France, from the Seine basin invented in late twelfth-century England.' east of Paris. In later years these were built But whether powered by water, wind, or up from segments of quartzite embedded animals, the essential of the grain mill was in plaster of Paris, held together with iron its massive millstones, up to sixteen 'hands' hoops. There is no archaeological evidence across, and for the best stones medieval that such composite stones were imported England relied on imports from the Euro- before the seventeenth century, but the pean continent. -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 61

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS Page NPAST AND PRESENT Notes and News . 5 Number 61 (2008) Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk Avril Lumley Prior . 7 The Peterborough Chronicles Nicholas Karn and Edmund King . 17 Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c. 1490-1500 Alan Rogers . 30 Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 Colin Davenport . 42 George London at Castle Ashby Peter McKay . 56 Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape Jenny Burt . 64 Politics in Late Victorian and Edwardian Northamptonshire John Adams . 78 The Wakerley Calciner Furnaces Jack Rodney Laundon . 86 Joan Wake and the Northamptonshire Record Society Sir Hereward Wake . 88 The Northamptonshire Reference Database Barry and Liz Taylor . 94 Book Reviews . 95 Obituary Notices . 102 Index . 103 Cover illustration: Courteenhall House built in 1791 by Sir William Wake, 9th Baronet. Samuel Saxon, architect, and Humphry Repton, landscape designer. Number 61 2008 £3.50 NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT PAST NORTHAMPTONSHIRE Northamptonshire Record Society NORTHAMPTONSHIRE PAST AND PRESENT 2008 Number 61 CONTENTS Page Notes and News . 5 Fact and/or Folklore? The Case for St Pega of Peakirk . 7 Avril Lumley Prior The Peterborough Chronicles . 17 Nicholas Karn and Edmund King Fermour vs Stokes of Warmington: A Case Before Lady Margaret Beaufort’s Council, c.1490-1500 . 30 Alan Rogers Daventry’s Craft Companies 1574-1675 . 42 Colin Davenport George London at Castle Ashby . 56 Peter McKay Rushton Hall and its Parklands: A Multi-Layered Landscape . -

ARCHAEOLOGY in SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980� Compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross

ARCHAEOLOGY IN SUFFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL FINDS, 1980 compiled by Edward Martin, Judith Plouviez and Hilary Ross Once again this is a selection of the new sites and finds discovered during the year. All the siteson this list have been incorporated into the County's Sites and Monuments Index; the reference to this is the final number given in each entry, preceded by the abbreviation S.A.U. Information for this list has been contributed by Miss E. Owles, Moyses Hall Museum; Mr C. Pendleton, Mildenhall Museum; Mr A. Pye, Lowestoft Archaeological Society; and Mr D. Sherlock. The drawings of the axes from Covehithe were kindly supplied by Mr P. Durbridge. Abbreviations: I. M. Ipswich Museum L.A.S. Lowestoft Archaeological and Local History Society M.H. MoysesHall Museum, Bury St Edmunds M.M. Mildenhall Museum S.A.U. Suffolk Archaeological Unit, Shire Hall, Bury St Edmunds T.M. Thetford Museum Pa Palaeolithic AS Anglo-Saxon Me Mesolithic MS Middle Saxon Ne Neolithic LS Late Saxon BA Bronze Age Md Medieval IA Iron Age PM Post-Medieval RB Romano-British UN Period unknown Aldringham (TM/4760). Ne. Flaked flint axe, found in a garden several years ago. (F. B. Macrae; S.A.U. ARG 008). Aldringham (TM/4759). Md. The disturbed remain.s of a skeleton, lying in an east-west grave, were found in a gas mains service trench at the end of the archway between the Thorpeness Almshouses. At least one other skeleton was intact beneath it and there may have been more. These are probably associated with the medieval St Mary's Chapel, Thorpe, which formerly existed in that area.