What Julian Saw: the Embodied Showings and the Items for Private Devotion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prayers for the Journey

PRAYERS FOR THE JOURNEY Julian of Norwich St Columba St Bede Bishop W. J. Carey A Prayer for Night Thomas Merton Dietrich Bonhoeffer From the Black Rock Prayer Book Prayers and Images for Reflection Julian of Norwich God said not: Thou shalt not be tempted, Thou shalt not be afflicted BUT Thou shalt not be overcome. Our falling hindereth him not to love us. Love was his meaning. Thou art enough to me. May 8, 1353 “It is enough, my Lord, enough indeed, My strength is in Thy might, Thy might alone.” St Columba Alone with none but Thee, O Lord, I journey on my way. What need I fear, if Thou art near, O King of night and day? More safe am I within Thine hand Than if an host did round me stand. St Bede Christ is the morning star who, when the night of this world is past, brings to his saints the promise of life and opens everlasting day. Alleluia. Durham Cathedral, Bede died in 735 a.d. A Prayer by Bishop W. J. Carey O Holy Spirit of God, come into my heart and fill me. I open the windows of my soul to let Thee in. I surrender my life to Thee. Come and possess me, fill me with light and truth. I offer to Thee the one thing I really possess: my capacity for being filled by Thee. Of myself I am an empty vessel. Fill me so that I may live the life of the Spirit: the life of Truth and Goodness; the life of Beauty and Love; the life of Wisdom and Strength. -

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks

Medieval Heritage and Pilgrimage Walks Cleveland Way Trail: walk the 3 miles from Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire to Helmsley Castle and tread in the footsteps of medieval Pilgrims along what’s now part of the Cleveland Way Trail. Camino de Santiago/Way of St James, Spain: along with trips to the Holy Land and Rome, this is the most famous medieval pilgrimage trail of all, and the most well-travelled in medieval times, at least until the advent of Black Death. Its destination point is the spot St James is said to have been buried, in the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Today Santiago is one of UNESCO’s World Heritage sites. Read more . the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela holds a Pilgrims’ Mass every day at noon. Walk as much or as little of it as you like. Follow the famous scallop shell symbols. A popular starting point, both today and in the Middle Ages, is either Le Puy in the Massif Central, France OR the famous medieval Abbey at Cluny, near Paris. The Spanish start is from the Pyrenees, on to Roncevalles or Jaca. These routes also take in the Via Regia and/or the Camino Frances. The Portuguese way is also popular: from the Cathedrals in either Lisbon or Porto and then crossing into Falicia/Valenca. At the end of the walk you receive a stamped certifi cate, the Compostela. To achieve this you must have walked at least 100km or cycled for 200. To walk the entire route may take months. Read more . The route has inspired many TV and fi lm productions, such as Simon Reeve’s BBC2 ‘Pilgrimage’ series (2013) and The Way (2010), written and directed by Emilio Estevez, about a father completing the pilgrimage in memory of his son who died along the Way of St James. -

Issue 18 • Spring 2014 Patron: the Duchess of Kent Singing Out!

NEWS FROM THE CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION The benefits of a Choir School education ISSUE 18 • SPRING 2014 PATRON: THE DUCHESS OF KENT SINGING OUT! l Canterbury Cathedral Girls’ Choir sang their first Evensong on Saturday 25 January which included music by Vaughan Williams, Dyson and SS Wesley. As the girls processed out from the Quire stalls they received a standing ovation. Under the baton of Assistant Organist, David COnHAIRMAN 22 November moreR thanOGER 100,000O youngVEREND people worldwide, WRITES including… Newsholme, the girls will initially sing at many of our choristers, sang the music of Benjamin Britten. They were services when the boy choristers are on celebrating the centenary of the birth of one of the greatest composers of their twice-termly breaks. Their next the 20th century. Evensong is on Saturday 29 March, followed by the Diocesan Service Our cathedrals and college chapels taken for granted and that they are fully celebrating the 20th anniversary of continued to ring with the sound of supported, musically, socially and Women’s Ministry on Saturday 10 May. glorious music sung by our choristers financially. Music of a high quality often The sixteen girls are aged 12-16 and attend through Christmas, with much of it brought comes at a price, but I believe that any eight different schools in the area. to the fore through radio and television. money spent on cathedral music pays for This term we are working towards Easter itself many times over. It gives pleasure to permeates each day and where what they and I asked Christopher Walji, Head the listener, engaging many entering our do is highly-respected by fellow non- Chorister of Rochester Cathedral, to reflect cathedrals and college chapels for the first chorister pupils. -

![1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9268/1-aquinas-treatise-on-law-summa-theologiae-1272-2-1-9780895267054-gateway-trans-509268.webp)

1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway Trans

PROGRAM OF LIBERAL STUDIES JUNIOR READING LIST PLS 33101, SEMINAR III Students are asked to purchase the indicated editions. With Instructor’s permission other editions may be used. Students are expected to have done the first reading when coming to the first meeting of the seminar. 1 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae [1272], 2.1, 9780895267054 Gateway trans. Parry, Questions 90-93 2 Aquinas, Treatise on Law, Summa Theologiae, Questions 94-97 3 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae 2.2, trans. Jordan, 9780268015039 Notre Dame Prologue-Pt 2-2, Quest 1, 2, (Art 1-4, 10), 3, 4, (Art 3-5) 4 Aquinas, On Faith, Summa Theologiae, Questions 6, 10 5 Dante, The Inferno, The Divine Comedy [1321], 9780553213393 Bantam Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 6 Dante, The Inferno, Cantos 18-34 7 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 1-18, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553213447 Bantam 8 Dante, Purgatorio, Cantos 19-33 9 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 1-17, trans. Mandelbaum 9780553212044 Bantam 10 Dante, Paradiso, Cantos 18-33 11 Petrarch, "Ascent of Mount Ventoux" [1336] and "On His 9780226096049 Chicago Own Ignorance and That of Many Others" [1370], trans Nachod, in The Renaissance Philosophy of Man, ed. Cassirer, Kristeller, Randall 12 Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales [1387-1400], trans. Coghill, "Prologue," 9780140424386 Penguin "Knight’s Tale," "Millers Tale," and "Nun’s Priest Tale" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 13 Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, "Pardoner’s Tale," "Wife of Bath’s Tale," "The Clerk’s Tale," "Franklin’s Tale," and "Retraction" (each tale with accompanying prologues and epilogues where appropriate) 14 Julian of Norwich, Showings [1393], trans. -

Human-Touch-2015.Pdf

The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, PROSE, AND VISUAL ART University of Colorado u Anschutz Medical Campus FRONT COVER artwork April 2010 #5, March 2013 #1, October 2011 #4, from the series Deterioration | DAISY PATTON Digital media BACK COVER artwork Act of Peace | JAMES ENGELN Color digital photograph University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Layout & Printing The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Volume 8 u 2015 BOOK LAYOUT / DESIGN EDITORS IN CHIEF: db2 Design Deborah Beebe (art director/principal) Romany Redman 303.898.0345 :: [email protected] Rachel Foster Rivard www.db2design.com Helena Winston PRINTING Light-Speed Color EDITORIAL BOARD: Bill Daley :: 970.622.9600 [email protected] Amanda Brooke Ryan D’Souza This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Anjali Dhurandhar License. To view a summary of this license, please see Lynne Fox http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. To review the license in Leslie Palacios-Helgeson full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. Amisha Singh To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. SUPERVISING EDITORS: * To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. Henry N. Claman Therese Jones © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright 2 3 University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus The Human Touch Volume 8 u 2015 Contents VOUME 8 u 2015 Preface ............................................................................................................ -

Booking-Guide-2015 Final.Pdf

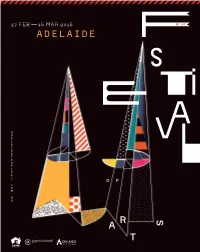

04_Welcomes Unsound Adelaide 50_Lawrence English, Container, THEATRE 20_Azimut Vatican Shadow, Fushitsusha BOLD, INNOVATIVE FESTIVAL 26_riverrun 51_Atom™ and Robin Fox, Forest Swords, 28_Nufonia Must Fall The Bug, Shackleton SEEKS LIKE-MINDED FRIENDS 30_Black Diggers 51_Model 500, Mika Vainio, Evian Christ, 36_Beauty and the Beast Hieroglyphic Being 38_La Merda 52_Mogwai Become a Friend to receive: 40_The Cardinals 53_The Pop Group 15% discount 41_Dylan Thomas—Return Journey 54_Vampillia 42_Beckett Triptych 55_65daysofstatic Priority seating 43_SmallWaR 56_Soundpond.net Late Sessions And much more 44_Jack and the Beanstalk 57_The Experiment 58_Late Night in the Cathedral: Passio DANCE Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet 59_Remember Tomorrow DISCOVER THE DETAILS 16_Mixed Rep 60_House of Dreams PAGE 70 OR VISIT ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU 18_Orbo Novo 61_WOMADelaide VISUAL 06_Blinc ADELAIDE 62_Adelaide Writers’ Week ARTS 10_Bill Viola: Selected Works WRITERS’ 66_The Third Plate: Dan Barber 68_Trent Parke: The Black Rose WEEK 67_Kids’ Weekend MUSIC 14_Danny Elfman’s Music from the MORE 70_Bookings Films of Tim Burton 71_Schools 72_Access Gavin Bryars in Residence 73_Map 23_Marilyn Forever 74_Staff 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble 75_Supporters and Philanthropy 24_Gavin Bryars Ensemble with guests 84_Corporate Hospitality 25_Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet and selected orchestral works FOLD OUT 84_Calendar 32_Fela! The Concert 34_Tommy 46_Blow the Bloody Doors Off!! Join us online 48_Abdullah Ibrahim 49_Richard Thompson Electric Trio #ADLFEST #ADLWW ADELAIDEFESTIVAL.COM.AU −03 Jay Weatherill Jack Snelling David Sefton PREMIER OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA MINISTER FOR THE ARTS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Welcome to the 30th Adelaide Festival of Arts. The 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts will please Greetings! It is my privilege and pleasure to In the performance program there is a huge range arts lovers everywhere with its broad program present to you the 2015 Adelaide Festival of Arts. -

Los Angeles Lawyer May 2016

ENTERTAINMENT32nd Annual THE MAGAZINE OF THE LOS ANGELES COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION LAW ISSUE MAY 2016 / $5 LIFE RIGHTS page 24 COPYRIGHT of ARTWORKS page 30 On Direct: Janna Sidley page 8 IP Rights in Bankruptcy page 11 Fairly Simple Los Angeles lawyers Michael C. Donaldson and Lisa A. Callif propose a three-question test for fair use in nonfiction page 16 2016 ENTERTAINMENT LAW ISSUE FEATURES 16 Fairly Simple BY MICHAEL C. DONALDSON AND LISA A. CALLIF While de minimis and statutory four-prong analyses of fair use are certainly to be considered, a three-question test may also apply Plus: Earn MCLE credit. MCLE Test No. 257 appears on page 19. 24 Rights to Life BY LEE S. BRENNER AND CATHY D. LEE The defense of newsworthiness applies to the common law and statutory causes of action for right of publicity 30 Copied in Stone BY MICHAEL D. KUZNETSKY AND MARK D. KESTEN Two recent cases concerning copyright infringement of large-scale sculptures involve complex issues of notice and registration, statute of limitations, and damages Los Angeles Lawyer DEPARTME NTS the magazine of the Los Angeles County 8 On Direct 35 By the Book Bar Association Janna Sidley Narrative of My Captivity among the May 2016 INTERVIEW BY DEBORAH KELLY Sioux Indians REVIEWED BY GREG VICTOROFF Volume 39, No. 3 10 Barristers Tips Steps to take in beginning a new legal 36 Closing Argument COVER PHOTO: TOM KELLER career Finding new perspectives on time to help BY VICTOR ORTIZ improve productivity BY AREZOU KOHAN 11 Practice Tips The disposition of intellectual property licenses in bankruptcy BY MICHAEL V. -

Tang WK & Kam Helen

Study Tour Report for the Medieval Germany, Belgium, France and England (Cathedral, Castle and Abbey --- a day visit in York) TANG Wai Keung / Helen KAM 1 Study Tour Report for the Medieval Germany, Belgium, France and England (Cathedral, Castle and Abbey --- a day visit in York) During this 8-day tour in England, we were requested to present a brief on York around its history, famous persons, attractive buildings and remarkable events etc. With the float of the same contents kept in minds even after the tour, we are prepared to write a study tour report based on this one-day visit with emphasis around its medieval period. York has a long turbulent period of history and, as King Edward VI said, “The history of York is the history of England”. This report will start with a brief history of York, which inevitably be related to persons, events and places we came across during this medieval tour. The report will also describe three attractions in York, viz., York Minster and its stained glass, Helmsley Castle and Rievaulx Abbey. 1 York's history The most important building in York is the York Minster, where in front of the main entrance, we found a statue of Constantine (photo 1). It reflects the height of Roman’s powers that conquered the Celtic tribes and founded Eboracum in this city; from here, the history of York started. 1.1 Roman York During our journey in the southern coast of England, Father Ha introduced to us the spots where the Roman first landed in Britain. -

Harlaxton Medieval Series (2017)

Copies of the Harlaxton Medieval Series are available from: SHAUN TYAS / PAUL WATKINS PUBLISHING, 1 High Street, Donington, Lincolnshire, PE11 4TA E: [email protected] T: +44 (0)1775 821 542 Harlaxton Medieval Studies I (Old Series) Proceedings of the 1984 Harlaxton Symposium: England in the Thirteenth Century, ed. W. M. Ormrod Articles: M. T. Clanchy, England in the Thirteenth Century: Power and Knowledge, 1–14 Adelaide Bennett, A Late Thirteenth-Century Psalter-Hours from London, 15–30 Michael Camille, Illustrations in Harley MS 3487 and the Perception of Aristotle’s Libri naturales in Thirteenth-Century England, 31–44 D. A. Carpenter, An Unknown Obituary of King Henry III from the Year 1263, 45–51 E. C. Fernie, Two Aspects of Bishop Walter de Suffield’s Lady Chapel at Norwich Cathedral, 52– 55 John Glenn, A Note on a Syllogism of Robert Grosseteste, 56–59 John Glenn, Notes on the Mappa Mundi in Hereford Cathedral, 60–63 Brian Golding, Burials and Benefactions: an Aspect of Monastic Patronage in Thirteenth-Century England, 64–75 George Henderson, The Imagery of St Guthlac of Crowland, 76–94 Virginia Jansen, Lambeth Palace Chapel, the Temple Choir, and Southern English Gothic Architecture of c. 1215–1240, 95–99 Flora Lewis, The Veronica: Image, Legend and Viewer, 100–106 Suzanne Lewis, Giles de Bridport and the Abingdon Apocalypse, 107–119 Michael Prestwich, The Piety of Edward I, 120–128 M. E. Roberts, The Relic of the Holy Blood and the Iconography of the Thirteenth-Century North Transept Portal of Westminster Abbey, 129–142 D. -

Organ Scholarship 2021-2022

Organ Scholarship 2021-2022 The Dean and Chapter of St Davids Cathedral wishes to appoint an Organ Scholar for the academic year beginning in September 2021. The scholarship is an outstanding opportunity for a gap-year or post-graduate organist to gain valuable training and experience as a church musician and play a full part in the musical life of a busy cathedral. The period of the appointment is usually for one year with the possibility to extend for a further year if appropriate. Please note: all the details shown here are subject to change depending on developing government guidance, rules and laws surrounding COVID-19. The Organ Scholarship was set up in 2016. Previous holders of the position have gone on to hold organist-posts at Tewkesbury Abbey; Ely Cathedral; Magdalen College, Oxford and St George’s Chapel, Windsor. The current post-holder, Michael D’Avanzo, has been appointed Organ Scholar of Southwell Minster. The scholarship is generously supported by the Friends of Cathedral Music (FCM), and by an anonymous donor who wishes to support and encourage the performance of Tudor church music at the cathedral. The successful candidate will have an interest in, and be willing to spend an appropriate portion of their time studying, performing and promoting Tudor music. St Davids St Davids is situated in the beautiful Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, West Wales. It is surrounded by some of the finest coastline in Europe and offers an unrivalled range of outdoor activities including walking, rock climbing, surfing, swimming and hiking. St Davids is an extremely popular tourist destination and hosts around half a million visitors every year. -

Copyrighted Material

18 Chapter 1 Julian in Context The contemporary rediscovery of the fourteenth‐century anchoress, Julian of Norwich, as an important mystical writer, theological thinker, and spiritual teacher has inevitably led to a great deal of speculation about her origins and life. Whatever the long‐term value of Julian’s teach- ings, no mystical or theological writing exists on some ideal plane removed from the historical circumstances in which it arose.1 Julian’s possible background and her historical context affect our con- temporary interpretation of what she wrote. Without some awareness of her context, it is all too easy to make Julian an honorary member of our own times or to pick and choose the aspects of her writings that appeal to us or to make overall judgments about her without seeking to honor what she herself intended to communicate in her writings. Who was Julian? Who Julian was, her social background, her education, her life experience prior to becoming an anchoress, when she became an anchoress – even where she was born – are all matters of speculation. The name “Julian” by which she is known is also likely to have been an adopted one. It was quite common for medieval anchorites and anchoresses to assume the name of the church to which their anchorhold (or cell) was physically attached. In COPYRIGHTEDthe case of Julian of Norwich, her MATERIALanchorhold was next to the parish church of St Julian Timberhill in Norwich which survives in reconstructed form to this day. The church has been known by that name since the tenth century but it is not absolutely clear to which St Julian it is dedicated. -

3: Julian of Norwich

7/7/2016 Essentials of Mysticism - Evelyn Underhill 3: Julian of Norwich ALL that we know directly of Julian of Norwich — the most attractive, if not the greatest of the English 183 mystics — comes to us from her book, The Revelations of Divine Love, in which she has set down her spiritual experiences and meditations. Like her contemporaries, Walter Hilton and the author of The Cloud of Unknowing, she lives only in her vision and her thought. Her external circumstances are almost unknown to us, but some of these can be recovered, or at least deduced, from the study of contemporary history and art; a source of information too often neglected by those who specialize in religious literature, yet without which that literature can never wholly be understood. Julian, who was born about 1342, in the reign of Edward III, grew up among the surroundings and influences natural to a deeply religious East Anglian gentlewoman at the close of the Middle Ages. Though she speaks of herself as " unlettered," which perhaps means unable to write, she certainly received considerable education, including some Latin, before her Revelations were composed. Her known connection with the Benedictine convent of Carrow, near Norwich, in whose gift was the anchorage to which she retired, suggests that she may have been educated by the nuns; and perhaps made her first religious profession at this house, which was in her time the principal "young ladies' school" of the Norwich diocese, and a favourite retreat of those adopting the religious life. During her most impressionable years she must have seen in 184 their freshness some of the greatest creations of Gothic art, for in Norfolk both architecture and painting had been carried to the highest pitch of excellence by the beginning of the fourteenth century.