Egypt: Lessons Learned from Constitution-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt's Presidential Election

From Plebiscite to Contest? Egypt’s Presidential Election A Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 Political Rights and Demands for Reform................................................................................ 2 Free and Fair? ................................................................................................................................ 4 From Plebiscite to Election: Article 76 Amended............................................................... 4 Government Restrictions and Harassment........................................................................... 5 Campaign Issues........................................................................................................................ 6 Judicial Supervision of Elections............................................................................................ 8 Election Monitoring ...............................................................................................................10 Appendix ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Political Parties and Candidates............................................................................................11 Introduction On September 7, Egypt will hold its first-ever presidential election, as distinct from the single-candidate plebiscites that have so far -

Egypt Presidential Election Observation Report

EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT JULY 2014 This publication was produced by Democracy International, Inc., for the United States Agency for International Development through Cooperative Agreement No. 3263-A- 13-00002. Photographs in this report were taken by DI while conducting the mission. Democracy International, Inc. 7600 Wisconsin Avenue, Suite 1010 Bethesda, MD 20814 Tel: +1.301.961.1660 www.democracyinternational.com EGYPT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OBSERVATION REPORT July 2014 Disclaimer This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Democracy International, Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ................................................................ 4 MAP OF EGYPT .......................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................. II DELEGATION MEMBERS ......................................... V ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ....................... X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 6 ABOUT DI .......................................................... 6 ABOUT THE MISSION ....................................... 7 METHODOLOGY .............................................. 8 BACKGROUND ........................................................ 10 TUMULT -

Calendar of Events 2005 Iv

PARLIAMENTARIANS FOR GLOBAL ACTION (PGA) INTERNATIONAL LAW & HUMAN RIGHTS PROGRAMME CALENDAR OF EVENTS 2005 February 9-10, 2005 The Rule of Law and the Protection of Civilians – the Role of Legislators Sub-regional two days meeting for Arab countries/Middle East and informal strategy meeting(s) on the ICC Venue: Parliament of Egypt, Cairo February 15, 2005 Presentation on the Implementation of the Rome Statute to the new Parliament of Uruguay Venue: Parliament of Uruguay, Montevideo February/March 2005 Seminar of the PGA Group in the European Parliament on “The International Criminal Court and Transatlantic Relations” Venue: European Parliament, Strasbourg April/May 2005 PGA participation in the conference “The ICC and Gender Justice: Obstacles to the implementation processes in the Andean region” Venue: Quito, Ecuador May 7-10, 2005 PGA session on the ICC on the occasion of the VI General Assembly of the Parliamentary Confederation of the Americas (COPA) Venue: Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil II Half 2005 Delegation of Legislators from a State Non-Party to the Rome Statute to the International Criminal Court Venues: ICC & international legal institutions, The Hague; Parliament of the Netherlands, The Hague II Half 2005 Meeting(s) of the Working Groups of the Consultative Assembly of Parliamentarians for the ICC & the Rule of Law Venue(s) to be determined October/November, 2006 IV plenary session of the Consultative Assembly of Parliamentarians for the ICC & the Rule of Law Venue(s) to be determined [Parliament of a State Non Party to the ICC Statute] -

Electoral System Dysfunction: the Arab Republic of Egypt Political

Nýsa, The NKU Journal of Student Research | Volume 1 | Fall 2018 Electoral System Dysfunction: The Arab Republic of Egypt Jarett Lopez is a political science major and history minor who will graduate in 2020. He has presented earlier works at statewide conferences and looks forward to continuing his research in the areas of creative placemaking and ref- erenda in the Ohio River Valley Tristate. Jarett plans to continue his research in political behavior and comparative politics and to attend graduate school. Political Science Political 15 Nýsa, The NKU Journal of Student Research | Volume 1 | Fall 2018 Electoral System Dysfunction: The Arab Republic of Egypt Jarett Lopez. Faculty mentor: Ryan Salzman Political Science Abstract Elections are the cornerstone of democratic systems, but the form they take and their overall quality varies widely. In this paper, electoral systems and their formulae for deciding a victor are analyzed using the Arab Republic of Egypt as a case study. This manuscript explores how the differences in electoral formulae influence voting behavior and gov- ernmental longevity. An analysis is done through a qualitative and quantitative study of Egyptian elections, beginning with Anwar Al-Sadat in 1970 and ending with Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi in 2018. We find that the Egyptian majoritarian sys- tem has not provided increased legitimacy, as suggested by the literature for a variety of reasons. This leads to further questions about the electoral formula in Egypt as well as the role of other institutions in the Egyptian political system. Keywords:MENA, Egypt, elections, electoral systems Introduction Literature Review: Electoral Systems and Elections The Arab Republic of Egypt is the state that now has political hegemony on an area in which human society Electoral systems are the processes through which offi- has grown and prospered for millennia. -

Failure of Muslim Brotherhood Movement on the Scene of Government in Egypt and Its Political Future

International Journal of Asian Social Science, 2015, 5(7): 394-406 International Journal of Asian Social Science ISSN(e): 2224-4441/ISSN(p): 2226-5139 journal homepage: http://www.aessweb.com/journals/5007 FAILURE OF MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD MOVEMENT ON THE SCENE OF GOVERNMENT IN EGYPT AND ITS POLITICAL FUTURE Rasoul Goudarzi1† --- Azhdar Piri Sarmanlou2 1,2Department of International Relations, Political Science Faculty, Islamic Azad University Central Tehran Branch, Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT After occurrence of public movements in Egypt that led the Egyptian Islamist movement of Muslim Brotherhood to come to power in ruling scene of this country, Mohamed Morsi as a candidate of this party won in the first democratic presidency elections in this country and after coming to power, he took a series of radical measures both in domestic and international scenes, which have caused him to be ousted in less than one year. The present essay is intended to reveal this fact based on theoretical framework of overthrowing government of Ibn Khaldun by proposing various reasons and documentations about several aspects of ousting of Morsi. Similarly, it indicates that with respect to removing this movement from Egypt political scene and confiscation of their properties, especially after the time when Field Marshal Abdel Fattah El-Sisi came to power as a president, so Muslim Brotherhood should pass through a very tumultuous path to return to political scene in Egypt compared to past time, especially this movement has lost noticeably its public support and backing. © 2015 AESS Publications. All Rights Reserved. Keywords: Muslim brotherhood, Army, Egypt, Political situation. Contribution/ Originality The paper's primary contribution is study of Mohamed Morsi‟s radical measures both in domestic and international scenes in Egypt, which have caused him to be ousted in less than one year. -

Master Thesis

MEASURES BY THE EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT TO COUNTER THE EXPLOITATION OF (SOCIAL) MEDIA - FACEBOOK AND AL JAZEERA Master Thesis Name: Rajko Smaak Student number: S1441582 Study: Master Crisis and Security Management Date: January 13, 2016 The Hague, The Netherlands Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media II Leiden University CAPSTONE PROJECT ‘FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION VERSUS FREEDOM FROM INTIMIDATION MEASURES BY THE EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT TO COUNTER THE EXPLOITATION OF (SOCIAL) MEDIA - FACEBOOK AND AL JAZEERA BY Rajko Smaak S1441582 MASTER THESIS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Crisis and Security Management at Leiden University, The Hague Campus. January 13, 2016 Leiden, The Netherlands Adviser: Prof. em. Alex P. Schmid Second reader: Dhr. Prof. dr. Edwin Bakker Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media III Leiden University Master Thesis: Measures by the Egyptian government to counter the exploitation of (social) media IV Leiden University Abstract During the Arab uprisings in 2011, social media played a key role in ousting various regimes in the Middle East and North Africa region. Particularly, social media channel Facebook and TV broadcast Al Jazeera played a major role in ousting Hosni Mubarak, former president of Egypt. Social media channels eases the ability for people to express, formulate, send and perceive messages on political issues. However, some countries demonstrate to react in various forms of direct and indirect control of these media outlets. Whether initiated through regulations or punitive and repressive measures such as imprisonment and censorship of media channels. -

European Parliament Resolution of 17 April 2014 on Syria: Situation in Certain Vulnerable Communities (2014/2695(RSP)) (2017/C 443/16)

22.12.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 443/79 Thursday 17 April 2014 P7_TA(2014)0461 Syria: situation of certain vulnerable communities European Parliament resolution of 17 April 2014 on Syria: situation in certain vulnerable communities (2014/2695(RSP)) (2017/C 443/16) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on Syria, in particular that of 6 February 2014 on the situation in Syria (1), — having regard to the Council conclusions on Syria of 14 April 2014 and 20 January 2014, — having regard to the statements of Vice-President / High Representative Catherine Ashton of 15 March 2014 on the 3rd anniversary of the Syrian uprising, and of 8 April 2014 in reference to the killing of Father Van der Lugt, SJ, in Homs, Syria, — having regard to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, — having regard to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the additional protocols thereto, — having regard to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, — having regard to the UN Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination based on Religion and Belief of 1981, — having regard to UN Security Council resolution 2139 of 22 February 2014, — having regard to the report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic of 12 February 2014, — having regard to the statement of the spokesperson for UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on Syria of 7 April 2014, — having regard to the statement of UN Emergency Relief Coordinator and Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs Valerie Amos on Syria of 28 March 2014, — having regard to the European Convention on Human Rights of 1950, and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union of 2000, — having regard to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, — having regard to Rules 122(5) and 110(4) of its Rules of Procedure, A. -

An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative

(Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin) An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Elon University Honors Program By Kelsey L. Glover April, 2011 Approved by: Dr. Laura Rose le, Thesis Mentor Dr. Brooke Barnett, Communications (Reader) Dr. Tim Wardle, Religious Studies (Reader) AI-Ikhwan al-Muslimin An Analysis of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood's Strategic Narrative Kelsey L. Glover (Dr. Laura Roselle) Department of International Studies-Elon University This study presents an in-depth qualitative analysis of the strategic narrative of the al Ikhwan al-Muslimin, also known as the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood is a politically active Islamic organization and has been a formidable player on the political scene as one of the only opposition groups for over eighty years. Given the recent revolution in Egypt, they could have a dramatic impact on the future of the country, and it becomes even more important to understand their strategic narrative, how it has changed over time, and how it could change in the future. In order to analyze these narratives in a systematic manner, I developed a coding instrument to analyze the organization's narratives from the beginning of2008 to the end of2010. The coding instrument, Atlas.ti, was used to code for themes and descriptions of grievances and remedies. I analyzed these narratives to look for reactionary changes and trends over time. My research suggests that there has been a discemable shift in their narrative from their more radical beginnings to a moderate Islamist, pro-democracy movement today. -

Copyright by Roy Edward Casagranda 2017

Copyright by Roy Edward Casagranda 2017 The Dissertation Committee for Roy Edward Casagranda Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Colonization of the Normative Realm in the Age of Instrumentality Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Per Urlaub John Hoberman Kathleen Higgins Robert Jensen Colonization of the Normative Realm in the Age of Instrumentality by Roy Edward Casagranda Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2017 Dedication To my mother, Awatif Istafanus Casagranda. Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been written without the endless and tireless help of my committee chair, Dr. Katherine Arens, and my wife, Dr. Banafsheh Madaninejad. I am also grateful to my committee: Dr. Kathleen Higgins, Dr. John Hoberman, Dr. Per Urlaub, and Dr. Robert Jensen for their support, feedback, and wonderful defense experience. In addition to those mentioned above, I am eternally indebted to Dr. Donald Lutz, Dr. Ross Lence, Dr. Phil Carspecken, Dr. Christian Davenport, Dr. Ken Brown, Dr. Pauline Kolenda, Dr. Cynthia Freeland, Prof. Charles Newkirk, and Prof. Bruce Hull for the profound impact that they have had on my understanding of the world. iv The Colonization of the Normative Realm in the Age of Instrumentality Roy Edward Casagranda, PhD University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Supervisor: Katherine Arens This dissertation aims to establish a contemporary model of why apolitical actors engage in the political realm. The project will intersperse practical cases with theoretical concerns. -

List of Participants

2007: Investing in Knowledge: Investing in the Future World Science Forum - Budapest 8 – 10 November 2007, Budapest, Hungary Special Session on “Investing in Science, Technology Mrs. Nadia EL-AWADY Managing Science Editor/Deputy Editor-in- and Innovation: Chief IslamOnline.net Challenges and Opportunities for Cairo EGYPT Parliaments” Cell phone: +2010-615-2228 Email: [email protected] 9 November 2007 Mrs. Ulla Burchardt, MP PARTICIPANTS Chairwoman of the Committee on Education, Research and Technology Assessment Mrs. Valeria ROMAN German Federal Parliament Science Journalist Deutscher Bundestag El Clarin newspaper, Argentina Platz der Republik World Federation of Science Journalist 11011 Berlin (WFSJ) GERMANY ARGENTINA Tel: 030 / 22 77 33 03 Fax: 030 / 22 77 63 03 Mr. Wilson DA SILVA Email: [email protected] Science Journalist Editor of Cosmos magazine Mr József PÁLINKÁS PO Box 589, Surry Hills 2010 Former Minister of Education Sydney AUSTRALIA HUNGARY Tel: +61 (0) 2 9219 2500 | Fax: +61 (0) 2 81 2360 Dr Ali ABBASPOUR, MP Majles Shoraye Eslami Mr. Jean-Marc FLEURY Islamic Consultative Assembly Jean-Marc Fleury Baharestan Square Executive Director TEHERAN World Federation of Science Journalists IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF) 28, Caron Street, Gatineau (Québec) Email : [email protected] Canada J8Y 1Y7 Email: [email protected] Dr. Hadi Doost Mohammadi Tel.: +819 770-0778 IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF) CANADA Dr. Ali Sarafroaz Yazdi Mr. Hepeng JIA IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF) Science Journalist Regional Coordinator China | SciDev.Net Mr. Moslem Mirzapour Beiyuan Road 86, IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF) Beijing 100101 CHINA Mrs. Mayra Gisela PEÑUELAS ACUÑA, MP [email protected] [email protected] Secretary of the Commission for Science and Tel : +86 (0) 10 84-85- 8195 Technology Chamber of Deputies Mr. -

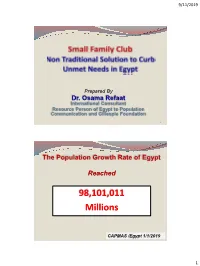

Egypt Experience to Reduce Unmet Needs for Family Planning

9/11/2019 Prepared By Dr. Osama Refaat International Consultant Resource Person of Egypt to Population Communication and Gillespie Foundation 1 The Population Growth Rate of Egypt Reached 98,101,011 Millions CAPMAS /Egypt 1/1/20192 1 9/11/2019 Population Census of Egypt January, 2019 Egypt Has 1 Newborn each 17 Second 3.5 Newborn / Minute 206 Newborn / Hour 4950 Newborn / Day 3 The Curve of Total Fertility Rate 1980 - 2017 6 5.3 5 4.9 4.4 4 4.1 3.6 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.3 3.4 3.2 3 3.1 3 2 1 0 1980 1984 1988 1991 1995 1997 1998 2000 2003 2005 2008 2014 2017 4 2 9/11/2019 The Unmet Needs for Family Planning in Egypt, CAPMAS, 2017 99.9% of women in the age group (15-49 years) are aware of the means of family planning, but the percentage of use does not exceed 58.5%. 12.6% of women have an unmet need for family planning methods. 5 MCH/MOHP Surveillance 20176 3 9/11/2019 7 Egypt Population Growth from 1965 to 2015 & Population Projections with Various Total Fertility Rate (TFR) Assumptions From 2015 To 2065 (Updated by Population communication/California) 8 4 9/11/2019 Average Cost of The Third Newborn On Egypt’s Government Budget, 2014 5447 Births / Day C/O. One Born / Year/ Ministry = LE3600 C/O. One Born /20 years /Ministry = LE72000 C/O. One Born/Year/ 30 Ministry = LE108000 X 20 Years LE2,160,000 CAPMAS/Ministry of Planning9 The Evolution Per Capita in Total Expenses in Egypt Ministry of Finance10 5 9/11/2019 Small Family Club The concept is to encourage the newly engaged, married and already married couples, changing their attitude towards the culture of having two educated children. -

Capacity Building and Implementation

2007: Investing in Knowledge: Investing in the Future World Science Forum Budapest 8 – 10 November 2007, Budapest, Hungary Special Session on “Investing in Science, Technology and Innovation: Challenges and Opportunities for Parliaments” organized by UNESCO and ISESCO Budapest, 9 November 2007 Facilitators: Mr. M. El Tayeb, Director Science Policy and Sustainable Development Division, UNESCO Ms. Diana Malpede, Science Policy and Sustainable Development Division, UNESCO 11.30-12:00 Opening of the Session Chair: Dr Werner Arber, 1978 Nobel Laureate in Medicine, Switzerland Opening Addresses: ¾ Dr. Katalin Szili, MP Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament ¾ E. Sylvester Vizi, President, Hungarian Academy of Sciences ¾ Mr. W. Erdelen Assistant Director General for Natural Sciences, UNESCO ¾ Dr. Mohammad Saaid Dayer Division of Sustainable Environment & Natural Resources ISESCO 12:00-12:45 Budgeting from Science and Technology Perspective: the Role of Parliaments Introductory Remarks by: Prof. M. R. Zou'bi, Director General, Islamic -World Academy of Science Chair: Mr. M. El Tayeb, Director, Science Policy and Sustainable Development Division, UNESCO Speakers: ¾ Dr. Hossam BADRAWI, MD.MP, Parliament of Egypt Shoura Council Upper House ¾ Ms. Slavica GRKOVSKA, MP, Chairperson Committee on Education, Science and Sports Assembly of the Republic of Macedonia ¾ Mr. Patrick Amuriat OBOYi, MP, Science and Technology Committee, Parliament of Uganda ¾ Mrs Ulla BURCHARDT, MP, Chairperson Committee on Education, Research and Technology Assessment German Federal Parliament Discussion 2007: Investing in Knowledge: Investing in the Future World Science Forum Budapest 8 – 10 November 2007, Budapest, Hungary 12:45-13:30 National and Regional Experiences in Science and Technology Budgeting Process Chair: Mr. Pallab Ghosh, BBC News, science correspondent, President of the World Federation of Science Journalists, United Kingdom Speakers: ¾ Dr.