Evaluation of the Cooperation Between Region Värmland and Karlstad University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Höghastighetståg Oslo–Karlstad– Stockholm

C Enskild motion Motion till riksdagen 2017/18:1495 av Daniel Bäckström (C) Höghastighetståg Oslo–Karlstad– Stockholm Förslag till riksdagsbeslut Riksdagen ställer sig bakom det som anförs i motionen om att ta ytterligare initiativ som utvecklar det svensk-norska samarbetet för planläggning och projektering av en driftssäker och snabb järnvägsförbindelse där resan tar högst tre timmar mellan Oslo och Stockholm, och detta tillkännager riksdagen för regeringen. Motivering Arbetet med att stärka tågens betydelse, kapacitet och konkurrenskraft pågår i såväl Norge som Sverige. Det genomförs projekt och utredningar för att analysera och beskriva förutsättningarna för investeringar i olika stråk och korridorer, på kort och lång sikt. Engagemanget och samarbetet mellan regionerna har stärkts de senaste åren och det har bildats bolag Oslo–Stockholm 2.5 AB i syfte att påskynda utbyggnaden av bättre tågtrafik mellan Oslo och Stockholm. Allt fler offentliga och privata aktörer lyfter nu betydelsen av en snabb järnvägsförbindelse och intresset ökar bland investerare och företag. Analyser som gjorts visar att sträckan har unika förutsättningar att vara en samhällsekonomisk investering. 16 företag från nio länder har haft ett första arbetsmöte i Örebro för att diskutera intäktsmodeller, finansieringsmodeller och modell för samverkan mellan företag, kommun och stat. Behovet av investeringar i infrastruktur är betydligt större än vad som kan göras med statlig anslagsfinansiering. Det är därför positivt att fler aktörer engagerar sig i frågan och ser betydelsen av att bygga infrastruktur som stärker den norsk-svenska arbetsmarknaden, ökar företagskontakterna, investeringarna och pendlingen. Sträckan Oslo–Karlstad–Stockholm är den mest intressanta när det gäller möjligheterna att få fler att resa med tåg istället för flyg, då ökningstakten är mycket högre på denna sträcka jämfört med till exempel Stockholm–Köpenhamn eller Oslo– Köpenhamn. -

Avtal Avtale

AVTAL AVTALE mellan mellom Samferdselsdepartementet och Samferdselsdepartementet og Trafikverket som Uppdragsgivare Trafikverket som Oppdragsgiver och og SJ AB som Leverantör SJ AB som Leverandør Om utfdrandet av internationell persontransport Om utførelse av internasjonal persontransport med tåg på sträckan med tog på strekningen Oslo-Karistad (- Oslo-Karlstad (-Stockholm) Stockholm) 1 Parterna 1 Partene Samferdselsdepartementet, Postboks Samferdselsdepartementet, Postboks 8010 Dep., 0030 Oslo och 8010 Dep., 0030 Oslo og Trafikverket, Box 810, 781 28 Trafikverket, Box 810, 781 28 Borlånge, nedan kallad Borlånge heretter benevnt Uppdragsgivaren. Oppdragsgiver. SJ AB, org.nr 556196-1599, 105 50 SJ AB, org.nr. 556196-1599, 105 50 Stockholm, nedan kallad Stockholm heretter benevnt Leverantören. Leverandør. Samferdselsdepartementet, Trafikverket och Samferdselsdepartementet, Trafikverket og SJ AB har slutit följande avtal med bilagor SJ AB har inngått følgende avtale med bilag (nedan kallat Avtalet) om köp av (benevnt som Avtalen) om kjøp av internationell persontransport med tåg på internasjonal persontransport med tog på sträckan Oslo-Karlstad (-Stockholm). strekningen Oslo-Karlstad (-Stockholm). 2 Avtalets bakgrund och syfte 2 Bakgrund og mål med avtalen Det Övergripande syftet med avtalet år att Det overordnede formål med avtalen er å uppråtta dagliga direkta tågförbindelser på skape daglige direkte togforbindelser på sträckan Oslo-Karlstad-Stockholm. Den strekningen Oslo-Karlstad-Stockholm. Det avtalade tågtrafiken ska genomföras mot avtalte togtilbudet skal drives på bakgrunn av bakgrund av ett nettokontrakt dår en nettokontrakt der Leverandøren har Leverantören ansvarar för både intåkter och ansvar for både inntekter og kostnader. Den kostnader. Den aktuella trafiken ingår som en aktuelle trafikken inngår som en del av SJ:s del av SJ:s ordinarie trafikutbud. -

What´S New in WUFI 1D Pro 4.2

What´s New in WUFI 1D Pro 4.2 Swedish GUI As we have a new cooperation with Lund University, the WUFI GUI runs now also in Swedish. New Material Data The material database has been extended with twenty generic materials from Sweden. Also the following products are part of the database: • Isofloc L • Getifix mineral insulation board ambio • Redstone mineral insulation board Pura New Climate Data (only in Version WUFI Pro) 12 new climate files for Sweden (Lund, Borlänge, Kiruna, Luleå, Umeå, Östersund, Karlstad, Stockholm, Norrköpping, Göteborg, Visby, Växjö). Also the 12 Test Reference Years of the Deutscher Wetterdienst from 1986 are now included with WUFI. 5 climate locations for Spain; Madrid, Barcelona, Bilbao, Malaga, Palma de Mallorca (Climate Files for Malaga and Palma de Mallorca are not ready yet). The location “Holzkirchen” contains now also a Moisture Reference Year including long-wave counterradiation from the atmosphere. EPW; Energy Plus Weather Files (only in Version WUFI Pro) Those Files can be downloaded for free at http://www.eere.energy.gov/buildings/energyplus and used for WUFI calculations. Note that they do not contain precipitation data. Adaptive Time Step Control (ATSC) This feature has been created to improve convergence behaviour in problematic situations. HTML based Help System All help systems of WUFI have been migrated to the HTML based help system. Some new features are not yet included in the help system. A future patch will updates this. Energy Performance Display Energy performance values of the construction are displayed in the assembly dialog. Warning System A warning system has been set up. -

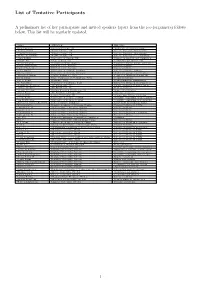

List of Tentative Participants

List of Tentative Participants A preliminary list of key participants and invited speakers (apart from the (co-)organizers) follows below. This list will be regularly updated. Name: Affiliation: Expertise: Greg Pavliotis Imperial College, UK Multiscale stochastic transp. Andrew Stuart Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, data assimil. Claudia Schillings Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, data assimil. Aretha Teckentrup Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, sci. computing Omar Lakkis University of Sussex, UK Numerical analysis and simulation Bangti Jin UCL, London, UK Computational inverse pbs. Otmar Scherzer Universit¨at Wien, Austria Inverse problems, param. estimation Sergei Pereverzyev RICAM, Linz, Austria Inverse problems Pavlo Tkachenko RICAM, Linz, Austria Inverse problems Peter Maass University of Bremen, Germany Inverse problems, sparsity Michael B¨ohm University of Bremen, Germany Multiscale param. identification Thomas Seidman UMBC Baltimore, USA Control of distributed networks Bj¨orn Birnir Univ. California at St. Barbara, USA Complex systems Ida de Bonis Bonvento, Italy Homogenization, singularities Vo Anh Khoa University of L'Aquila, Italy Inverse problems, homogenization Alessandro Corbetta TU Eindhoven, NL Crowd dynamics/Fokker Planck Arthur Vromans TU Eindhoven, NL Homogenization Mounir Zeitouni Philips Research Eindhoven, NL Source identification Marta Regis TU Eindhoven/Philips, NL Bayesian statistics Sander Hille Leiden University, NL Semigroups, Inverse problems Florin Radu University of Bergen, Norway Scientific computing, -

Relocation of Government Agencies (Rir 2009:30)

AUDIT REPORT, SUMMARY 1 Summary Relocation of government agencies (RiR 2009:30) SWEDISH NATIONAL AUDIT OFFICE SUMMARY 1 DATE: 16-12-2009 Relocation of government agencies Riksrevisionen (the Swedish National Audit Office) has examined the effects of the relocations of government agencies that were carried out to compensate regions for the disbandment of military units as a result of the 2004 defence-policy review. We ask the following questions in our audit: Did the regions obtain full compensation for disbandment through the relocations? Have the operations of the agencies recovered? And were the costs in line with expectations? Even though several waves of agency relocations have taken place in Sweden over several decades, no overall evaluation has been made of this issue. Hence nobody knows for certain whether the regions where new jobs were created as a result of, say, the disbandment of military units actually received compensation in full. 2,700 jobs were to be relocated Several regions were affected by the disbandment or relocation of military units as a result of the 2004 defence-policy review. The Riksdag (parliament) therefore decided to take measures to compensate the four regions – Östersund, Karlstad/Kristinehamn, Arvidsjaur and Gotland – most heavily affected by the restructuring of the armed forces. Besides several other projects and the transfer of financial resources to those regions, it was also announced that central-government agencies would be established or moved there to a significant extent. The government jobs that were going to disappear in those regions would thus be replaced by new ones, in that government agencies or parts of them would be relocated from Stockholm. -

Sharing Towns the Key to the Sharing Economy Puzzle

Sharing Towns The Key to the Sharing Economy Puzzle April 2019 Sharing Cities Sweden is a national program for the sharing economy in cities. The program aims to put Sweden on the map as a country that actively and critically works with the sharing economy in cities. The objectives of the program are to develop world- leading test-beds for the sharing economy in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö and Umeå, and to develop a national node in order to significantly improve national and international cooperation and promote an exchange of experience on sharing cities. Title: The Key to the Sharing Economy Puzzle Authors: Kelly Delaney, Alexandra Jonca, Samuel Kalb Sharing Cities Sweden is carried out within Viable Cities, a Swedish Innovation Programme for smart sustainable cities, jointly funded by the Swedish Innovation Agency (VINNOVA), the Swedish Energy Agency and the Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS). 2 Executive Summary The aim of this report is to address the problem of consumption in Karlstad by providing a tool, the Key to the Sharing Economy puzzle, to help multiple actors make sense of the Sharing Economy and use it to achieve Karlstad’s goals. This tool will organise conversations and discussions by providing a systematic way of approaching the Sharing Economy, and will help ask and answer important questions to make better decisions about sharing initiatives. It was designed specifically for the Karlstad context but will also prove useful for cities with similar sizes, opportunities and challenges. We provide two types of recommendations for Karlstad in this report. -

IV.5 Knowledge, Engagement and Higher Education in Europe

While European universities have much to at an early, peripheral phase, and the central offer European society in the field of commu- challenge is in placing it at the heart of IV.5 nity engagement, there is an urgent challenge university life. KNOWLEDGE, to improve their current performance. A great ENGAGEMENT deal is demanded across all walks of society AND HIGHER for the knowledge emanating from universi- SOCIETAL ENGAGEMENT IN EUROPE EDUCATION IN ties, and for the exchange and co-production of knowledge with universities, and a failure European universities have been inextricably EUROPE to respond will undermine popular support tied up with their host societies since their for the sector. University work in engagement foundation, and universities’ institutions http://www.guninetwork.org/. Paul Benneworth and occurs against a range of competing forces, and ideas have evolved along with their host Michael Osborne including modernization, internationalization societies. Universities have always faced a and budget cuts. As a consequence, universi- dependency on sponsors, which has influ- website ties are faced with having to make strategic enced their relationships with society. As their choices and are being overloaded with Biggar (2010, p. 77) notes: on missions; seemingly less important missions [email protected]. risk becoming peripheral within this scenario. Right from their medieval beginnings, Nonetheless, there is much that is [universities] have served private purposes contact outstanding in European universities in terms and practical public purposes as well as Innovation of community engagement, and in this chap- the sheer amor scientiae [‘knowledge for for ter we provide a historical and contemporary knowledge’s sake’] … popes and bishops please background as well as many examples of needed educated pastors and they and kings exemplary practice. -

Study Plan for Doctoral Studies in Computer Science

Reg.no: HNT2021/133 Faculty of Health, Science and Technology Study Plan for Doctoral Studies in Computer Science (Utbildning på forskarnivå i Datavetenskap) Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Telephone 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] KAU.SE Reg.no: HNT2021/133 Computer Science Study Plan Approval The study plan was approved by the Faculty Board of Health, Science and Technology on 23 April 2020 and valid from this date. Revised by the Faculty Board of Health, Science and Technology on 18 March 2021 and valid from this date. General stipulations for PhD programmes are provided in the Higher Education Act and in the Higher Education Ordinance. The PhD programme is offered to the extent permitted by available resources. 1. General Information The subject Computer Science includes everything from studies of hardware in computer systems to the design of software to be executed in these computer systems. Computer Science is a broad field of science ranging from basic theoretical studies of algorithms and their complexity to more applied areas such as software development, compiler construction, database technology, computer networking, data security, personal integrity, artificial intelligence and more. The research at Karlstad University focuses on software development, computer networking, data security and personal integrity. 2. Programme Outcomes The general outcomes of licentiate or doctoral studies in terms of knowledge and understanding, competence and skills, and judgement and approach are specified as follows in the System of Qualifications (Higher Education Ordinance, annex 2): Degree of Licentiate Knowledge and understanding For a Degree of Licentiate the third-cycle student shall demonstrate knowledge and understanding in the field of research including current specialist knowledge in a limited area of this field as well as specialised knowledge of research methodology in general and the methods of the specific field of research in particular. -

Sleep-Related Cognitive Processes and the Incidence of Insomnia Over Time: Does Anxiety and Depression Impact the Relationship?

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 21 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.677538 Sleep-Related Cognitive Processes and the Incidence of Insomnia Over Time: Does Anxiety and Depression Impact the Relationship? Annika Norell-Clarke 1,2*, Mikael Hagström 3 and Markus Jansson-Fröjmark 4,5 1 Department of Social and Psychological Studies, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden, 2 Department of Health Sciences, Kristianstad University, Kristianstad, Sweden, 3 Department of Psychology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 4 Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Centre for Psychiatry Research, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 5 Stockholm Health Care Services, The Centre for Psychotherapy, Education & Research, Region Stockholm, Stockholm, Sweden Aim: According to the Cognitive Model of Insomnia, engaging in sleep-related cognitive processes may lead to sleep problems over time. The aim was to examine associations between five sleep-related cognitive processes and the incidence of insomnia, and to investigate if baseline anxiety and depression influence the associations. Methods: Two thousand three hundred and thirty-three participants completed surveys Edited by: Bjørn Bjorvatn, on nighttime and daytime symptoms, depression, anxiety, and cognitive processes at University of Bergen, Norway baseline and 6 months after the first assessment. Only those without insomnia at baseline Reviewed by: were studied. Participants were categorized as having or not having incident insomnia at Børge Sivertsen, the next time point. Baseline anxiety and depression were tested as moderators. Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), Norway Results: Three cognitive processes predicted incident insomnia later on. Specifically, Enrico Giora, Vita-Salute San Raffaele more safety behaviors and somatic arousal at Time 1 increased the risk of developing University, Italy insomnia. -

Personnel Reviewers 2016 Personnel Reviewers 2016

Personnel reviewers 2016 Personnel reviewers 2016 List of reviewers from 1 January to 31 December 2016 171 Abdul Kohar, Umar Haiyat Al-Waqfi, Mohammed Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia United Arab Emirates University, Accquaah, Moses United Arab Emirates University of North Carolina Greensboro, Andersen, Torben USA University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Açıkgöz, Atif Anderson, Valerie Fatih University, Turkey University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom Adikaram, Arosha of Great Britain and Northern Ireland University of Colombo, Sri Lanka Arevshatian, Lilith Afiouni, Fida Kingston University, United Kingdom of American University of Beirut, Lebanon Great Britain and Northern Ireland Agarwal, Madhushree Aristovnik, Aleksander Management Development Institute, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Gurgaon, India Armstrong, Craig Agarwal, Upasna A. University of Alabama, USA NITIE, India Arndt, Aaron Agarwala, Tanuja Old Dominion University, USA University of Delhi, India Arnold, John Ahmed, Masoom Arora, Ridhi Glyndwr University, United Kingdom of LM Thapar School of Management, Great Britain and Northern Ireland Thapar University Patiala, India Akyüz, Kadri Cemil Audenaert, Mieke Karadeniz Technical University, University Ghent, Belgium Turkey Aydin, Erhan Albadry, Omaima Brunel University, United Kingdom of Great Alegre, Joaquin Britain and Northern Ireland University of Valencia, Spain Backhaus, Kristin Alghamdi, Ibrahim SUNY New Paltz, United Kingdom of Great Glasgow Caledonian University, United Britain and Northern Ireland Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Bainbridge, Hugh Ireland University of New South Wales, Alhejji, Hussain Australia University of Limerick, Ireland Balabanova, Evgeniya Allen, Mathew Higher School of Economics, Manchester University, United Kingdom of Russian Federation Great Britain and Northern Ireland Ballesteros, José Alony, Irit Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Personnel Review University of Wollongong, Australia Canaria, Spain Vol. -

|70| Stockholm-Karlstad-Oslo

Stockholm-Karlstad-Oslo Alla tåg Stockholm-Hallsberg tab 61, |70| alla tåg Kristinehamn-Karlstad-Kil tab 76 30 okt 2016-10 dec 2016 VTAB VTAB VTAB VTAB VTAB SJ SJ TÅGK TÅGK VTAB VTAB VTAB Tågab VTAB Uppdaterad 30 okt 2016 2 2 2 2 2 Snabbtåg Reg 2 2 2 2 2 2 TiB TiB Tågnummer 8901 18903 8903 8905 8981 619 355 18907 18907 8983 8907 8985 7001 8909 Period Dagar M-F M-F M-F M-F M-F M-F Dagl SoH L M-F M-F M-F M-F M-F km Går även / Går ej 2 3 0 fr Stockholm C 5.55 15 fr Flemingsberg | 36 fr Södertälje Syd | 63 fr Gnesta | 108 fr Flen | fr Linköping C 56 fr Norrköping C 56 t Katrineholm C 56 131 fr Katrineholm C | 152 fr Vingåker | 197 t Hallsberg 7.08 fr Örebro C 64 5.50 6.22 6.52 t Hallsberg 64 6.08 6.42 7.10 197 fr Hallsberg 6.10 7.08 7.12 227 t Laxå | | | 227 fr Laxå | | | 227 t Degerfors 6.41 | 7.41 fr Degerfors 1 7.00 8.05 t Karlskoga busstn 1 7.30 8.35 261 fr Degerfors 6.42 | 7.42 287 t Kristinehamn 7.01 | 8.00 287 fr Kristinehamn 6.00 7.02 7.20 | 8.02 8.15 9.15 9.22 305 fr Väse 6.11 7.12 7.29 | 8.15 8.23 9.25 | 322 fr Välsviken 6.23 7.21 7.43 | 8.24 8.34 9.35 | 327 t Karlstad C 6.27 7.26 7.47 8.04 8.29 8.39 9.39 9.44 327 fr Karlstad C 5.41 6.50 7.32 8.06 8.13 8.43 8.43 8.48 9.46 9.58 347 t Kil 5.54 7.02 7.47 | 8.26 8.57 8.57 9.02 9.58 10.10 347 fr Kil 5.57 7.04 7.49 | 9.04 9.04 9.05 10.13 353 fr Fagerås 6.03 7.08 7.54 | 9.09 9.09 9.10 10.18 359 fr Lene | 7.13 7.59 | | | | | 363 fr Högboda 6.10 7.16 8.12 | 9.16 9.16 9.17 10.25 372 fr Brunsberg 6.16 7.22 8.19 | | | | | 381 fr Edane 6.22 7.28 8.24 | 9.27 9.27 9.28 10.36 395 t Arvika 6.31 -

BERGEN SUMMER RESEARCH SCHOOL #Bsrs2016

PROGRAMME BERGEN SUMMER RESEARCH SCHOOL WATER, CLIMATE & SOCIETY UNIVERSITY OF BERGEN JUNE 13 - 24, 2016 #bsrs2016 WATER, CLIMATE & SOCIETY Welcome to Bergen Summer Research School 2016 For nine years, the University of Bergen and the other academic institutions in Bergen have invited to a summer research school exploring “Global Development Challenges”. This spring, the World Economic Forum ranked for the first time the water crisis as the greatest global risk to economies, environments and societies in the forthcoming decade. Last year, NATO held their largest military exercise since the Cold War simulating war over water. The UN’s General Secretary and the World Bank have argued that management of water is crucial to future developments. This year, the Summer Research School will approach global challenges related to “Water, Climate & Society” from many disciplines through plenary sessions, keynote lectures, and in particular through the seven parallel courses: • Climate change and water • Modelling the complexities of water, climate and society • Poverty, climate change and water in the context of SDGs • River basins, power and law • The ocean, climate and society • Religion and water • Water and global health BSRS seeks to create a unique environment for participants to present, engage, discuss, progress their thinking, and improve on their work. As part of the taught courses, there will be an excursion into the waterscape of western Norway to explore the impact rivers, fjords and glaciers have had on societies. We are happy to welcome you to the city of Bergen and to the large academic milieu of high quality research. We hope you will gain knowledge, new perspectives, as well as new acquaintances that will benefit your academic work.