Sleep-Related Cognitive Processes and the Incidence of Insomnia Over Time: Does Anxiety and Depression Impact the Relationship?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Tentative Participants

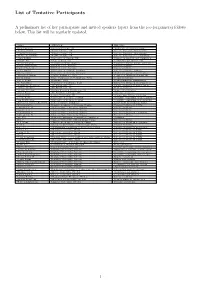

List of Tentative Participants A preliminary list of key participants and invited speakers (apart from the (co-)organizers) follows below. This list will be regularly updated. Name: Affiliation: Expertise: Greg Pavliotis Imperial College, UK Multiscale stochastic transp. Andrew Stuart Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, data assimil. Claudia Schillings Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, data assimil. Aretha Teckentrup Warwick Univ., UK Inverse Bayesian, sci. computing Omar Lakkis University of Sussex, UK Numerical analysis and simulation Bangti Jin UCL, London, UK Computational inverse pbs. Otmar Scherzer Universit¨at Wien, Austria Inverse problems, param. estimation Sergei Pereverzyev RICAM, Linz, Austria Inverse problems Pavlo Tkachenko RICAM, Linz, Austria Inverse problems Peter Maass University of Bremen, Germany Inverse problems, sparsity Michael B¨ohm University of Bremen, Germany Multiscale param. identification Thomas Seidman UMBC Baltimore, USA Control of distributed networks Bj¨orn Birnir Univ. California at St. Barbara, USA Complex systems Ida de Bonis Bonvento, Italy Homogenization, singularities Vo Anh Khoa University of L'Aquila, Italy Inverse problems, homogenization Alessandro Corbetta TU Eindhoven, NL Crowd dynamics/Fokker Planck Arthur Vromans TU Eindhoven, NL Homogenization Mounir Zeitouni Philips Research Eindhoven, NL Source identification Marta Regis TU Eindhoven/Philips, NL Bayesian statistics Sander Hille Leiden University, NL Semigroups, Inverse problems Florin Radu University of Bergen, Norway Scientific computing, -

IV.5 Knowledge, Engagement and Higher Education in Europe

While European universities have much to at an early, peripheral phase, and the central offer European society in the field of commu- challenge is in placing it at the heart of IV.5 nity engagement, there is an urgent challenge university life. KNOWLEDGE, to improve their current performance. A great ENGAGEMENT deal is demanded across all walks of society AND HIGHER for the knowledge emanating from universi- SOCIETAL ENGAGEMENT IN EUROPE EDUCATION IN ties, and for the exchange and co-production of knowledge with universities, and a failure European universities have been inextricably EUROPE to respond will undermine popular support tied up with their host societies since their for the sector. University work in engagement foundation, and universities’ institutions http://www.guninetwork.org/. Paul Benneworth and occurs against a range of competing forces, and ideas have evolved along with their host Michael Osborne including modernization, internationalization societies. Universities have always faced a and budget cuts. As a consequence, universi- dependency on sponsors, which has influ- website ties are faced with having to make strategic enced their relationships with society. As their choices and are being overloaded with Biggar (2010, p. 77) notes: on missions; seemingly less important missions [email protected]. risk becoming peripheral within this scenario. Right from their medieval beginnings, Nonetheless, there is much that is [universities] have served private purposes contact outstanding in European universities in terms and practical public purposes as well as Innovation of community engagement, and in this chap- the sheer amor scientiae [‘knowledge for for ter we provide a historical and contemporary knowledge’s sake’] … popes and bishops please background as well as many examples of needed educated pastors and they and kings exemplary practice. -

Study Plan for Doctoral Studies in Computer Science

Reg.no: HNT2021/133 Faculty of Health, Science and Technology Study Plan for Doctoral Studies in Computer Science (Utbildning på forskarnivå i Datavetenskap) Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Telephone 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] KAU.SE Reg.no: HNT2021/133 Computer Science Study Plan Approval The study plan was approved by the Faculty Board of Health, Science and Technology on 23 April 2020 and valid from this date. Revised by the Faculty Board of Health, Science and Technology on 18 March 2021 and valid from this date. General stipulations for PhD programmes are provided in the Higher Education Act and in the Higher Education Ordinance. The PhD programme is offered to the extent permitted by available resources. 1. General Information The subject Computer Science includes everything from studies of hardware in computer systems to the design of software to be executed in these computer systems. Computer Science is a broad field of science ranging from basic theoretical studies of algorithms and their complexity to more applied areas such as software development, compiler construction, database technology, computer networking, data security, personal integrity, artificial intelligence and more. The research at Karlstad University focuses on software development, computer networking, data security and personal integrity. 2. Programme Outcomes The general outcomes of licentiate or doctoral studies in terms of knowledge and understanding, competence and skills, and judgement and approach are specified as follows in the System of Qualifications (Higher Education Ordinance, annex 2): Degree of Licentiate Knowledge and understanding For a Degree of Licentiate the third-cycle student shall demonstrate knowledge and understanding in the field of research including current specialist knowledge in a limited area of this field as well as specialised knowledge of research methodology in general and the methods of the specific field of research in particular. -

Personnel Reviewers 2016 Personnel Reviewers 2016

Personnel reviewers 2016 Personnel reviewers 2016 List of reviewers from 1 January to 31 December 2016 171 Abdul Kohar, Umar Haiyat Al-Waqfi, Mohammed Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia United Arab Emirates University, Accquaah, Moses United Arab Emirates University of North Carolina Greensboro, Andersen, Torben USA University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Açıkgöz, Atif Anderson, Valerie Fatih University, Turkey University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom Adikaram, Arosha of Great Britain and Northern Ireland University of Colombo, Sri Lanka Arevshatian, Lilith Afiouni, Fida Kingston University, United Kingdom of American University of Beirut, Lebanon Great Britain and Northern Ireland Agarwal, Madhushree Aristovnik, Aleksander Management Development Institute, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia Gurgaon, India Armstrong, Craig Agarwal, Upasna A. University of Alabama, USA NITIE, India Arndt, Aaron Agarwala, Tanuja Old Dominion University, USA University of Delhi, India Arnold, John Ahmed, Masoom Arora, Ridhi Glyndwr University, United Kingdom of LM Thapar School of Management, Great Britain and Northern Ireland Thapar University Patiala, India Akyüz, Kadri Cemil Audenaert, Mieke Karadeniz Technical University, University Ghent, Belgium Turkey Aydin, Erhan Albadry, Omaima Brunel University, United Kingdom of Great Alegre, Joaquin Britain and Northern Ireland University of Valencia, Spain Backhaus, Kristin Alghamdi, Ibrahim SUNY New Paltz, United Kingdom of Great Glasgow Caledonian University, United Britain and Northern Ireland Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Bainbridge, Hugh Ireland University of New South Wales, Alhejji, Hussain Australia University of Limerick, Ireland Balabanova, Evgeniya Allen, Mathew Higher School of Economics, Manchester University, United Kingdom of Russian Federation Great Britain and Northern Ireland Ballesteros, José Alony, Irit Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Personnel Review University of Wollongong, Australia Canaria, Spain Vol. -

BERGEN SUMMER RESEARCH SCHOOL #Bsrs2016

PROGRAMME BERGEN SUMMER RESEARCH SCHOOL WATER, CLIMATE & SOCIETY UNIVERSITY OF BERGEN JUNE 13 - 24, 2016 #bsrs2016 WATER, CLIMATE & SOCIETY Welcome to Bergen Summer Research School 2016 For nine years, the University of Bergen and the other academic institutions in Bergen have invited to a summer research school exploring “Global Development Challenges”. This spring, the World Economic Forum ranked for the first time the water crisis as the greatest global risk to economies, environments and societies in the forthcoming decade. Last year, NATO held their largest military exercise since the Cold War simulating war over water. The UN’s General Secretary and the World Bank have argued that management of water is crucial to future developments. This year, the Summer Research School will approach global challenges related to “Water, Climate & Society” from many disciplines through plenary sessions, keynote lectures, and in particular through the seven parallel courses: • Climate change and water • Modelling the complexities of water, climate and society • Poverty, climate change and water in the context of SDGs • River basins, power and law • The ocean, climate and society • Religion and water • Water and global health BSRS seeks to create a unique environment for participants to present, engage, discuss, progress their thinking, and improve on their work. As part of the taught courses, there will be an excursion into the waterscape of western Norway to explore the impact rivers, fjords and glaciers have had on societies. We are happy to welcome you to the city of Bergen and to the large academic milieu of high quality research. We hope you will gain knowledge, new perspectives, as well as new acquaintances that will benefit your academic work. -

Sustainable IT Collaboration Around the Globe 16Th Americas Conference on Information Systems August 12-15, 2010

Sustainable IT Collaboration Around the Globe 16th Americas Conference on Information Systems August 12-15, 2010 Hosted by: A conference of the Association for Information Systems Table of Contents General Conference Overview ........................................................... 4 Welcome from the Conference Chairs ................................................ 5 Welcome from the Program Chairs .................................................... 6 Welcome from AIS President and Executive Director ............................ 8 Conference Committee .................................................................... 9 Sponsors & Exhibitors ................................................................... 11 Conference Information ................................................................. 12 Conference Highlights Social Events ........................................................................... 14 Keynote Speaker ..................................................................... 15 Doctoral Consortium ................................................................. 16 MIS Camp ............................................................................... 18 CIO Symposium ....................................................................... 20 LEO/Fellows Session ................................................................. 22 Track and Mini-Track Chairs ........................................................... 23 Best Paper Nominations................................................................ -

Karlstad University Address: Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88

Application Process For a student being able to apply, our partner universities first must nominate their students online on Moveonnet. Information about this is sent to all partner universities before the deadline. When the student has been nominated instructions on how and where to apply will be sent directly to the student, with a copy to the coordinator. Application and admission - exchange students Application Deadlines Karlstad University Beginning of April for Semester 1 or Full Year applicants Address: Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88 Karlstad, Beginning of October for Semester 2 applicants Main Web Address: http://www.kau.se/en Language of Study University Introduction For courses taught in English, a good knowledge of As one of the youngest universities in Sweden, we English is required. Non-native speakers of English hope to be more adventurous in challenging the may be required to prove their knowledge of established and exploring the unknown. English. Language requirements Karlstad University offers Swedish language courses Our ambition is to contribute to the development of for exchange students. The courses provide some knowledge at international, regional and individual practical skills in the Swedish language as well as a levels. Thanks to our openness, creativity and multi- brief survey of Swedish society and Swedish culture. disciplinary approach, we have already attained a significant level of academic achievement. All our Swedish language courses education and research is underpinned by a close Course Catalogue: Courses taught in English dialogue with private companies and public organisations. We can also offer one of the most Credits inspirational university environments in the Modules are credited in ECTS (European Credit country. -

Education at Karlstad University, Sweden, Since 2009

May-Brith Ohman Nielsen Professor dr. philos. Department for religion, philosophy and history, Agder University. Current positions: Professor of history, Agder University, Norway. Employed at Agder University since 1989 as lecturer and researcher. Permanent position as associate professor from 1997, professor from 2006. Current main position. Professor of history education at Karlstad University, Sweden, since 2009. Editor of the Scandinavian Journal of History, since 2003. Office. Head of the committee for humanities, FRIHUM, at the Norwegian Research Council, since 2010. Office. Previous positions: Pd. D. fellow in history, Bergen University, 1992-1996. Associate professor II, Bergen University College, 1999-2004. Education: Dr. Philos. in history 1997. Other subjects: biology, sports, education and social sciences. Educated at Bergen University and Bergen University College. Publications, research and presentations: Major and recent works, brief presentations: http://maybrithohmannielsen.wordpress.com/about/ http://maybrithohmannielsen.wordpress.com/category/norsk/ http://maybrithohmannielsen.wordpress.com/category/english/ Supplementary list of the majority of works, see the Cristin national register: http://www.cristin.no/as/WebObjects/cristin.woa/wa/fres?sort=ar&pnr=329263&la=no&action=sok Offices, boards, (elected and/or appointed), adviser assignments, since 1990: The Research Council of Norway, Committee for humanities, FRIHUM, leader 2010 ʹ Stiftelsen Fædrelandsvennen A/S, (media house and newspaper), board member 2008 ʹ Agder -

Prosperity and Growth Strategy Karlstad Region Strategy Proposals

Prosperity and Growth Strategy Karlstad Region Strategy Proposals TENTacle WP 4.1 Version: Final 10/06/2018 1 Content Summary 1 Introduction 2 Project Goal 3 Basic Report Conclusions and Scenarios 3.1 Growth 3.2 Politics 3.3 Industry Sector 3.4 Culture Sector 3.5 University Sector 3.6 Public Sector 3.7 Transport Sector 3.8 Employment 3.9 Population 4 Population Goal 5 Vision Karlstad 2040 5.1 Vision 5.2 Conditions 5.3 Driving Forces 5.4 The Honeycomb 6 Suggested Strategic Activities 6.1 Democracy and Politics 6.2 Innovation and Entrepreneurship 6.3 Research and Education 6.4 Asylum Immigrants Involvement 7 Railway System Demands 8 Impacts on Growth 9 Implementation References 2 Summary Värmland's share of the Swedish population is declining since 1860, when it peaked. Over the past 40 years, Karlstad´s share is unchanged. The increase in figures depends to more than 50% of influx from the other 15 municipalities in Värmland. Almost 50% are retired. When it comes to regional GDP, Värmland was number 13 of 24 counties in 1860. Today, the position is 22. Nor- dregio's Regional Potential Index expresses the economic prospects of regions. Värmland is ranked 58 of 74 Nordic regions. In Sweden, only Gävleborg region has a lower position. In global terms, regarding the effects of the digital revolution on future employment, we can expect a decline in man- ufacturing, retail trade and transport on roads. At the same time, we see a very strong increase of the employment in the information technology sector and other high-tech industries. -

EXCHANGE STUDENT GUIDE Five Campuses in FIVE CITIES

University of Southern Denmark EXCHANGE STUDENT GUIDE Five campuses IN FIVE CITIES See the world. Build your career. Find friends for life. Make studying abroad what you want it to be at the University of Southern Denmark. Our international Exchange programmes offer flexibility and choice so you can get the most out of your time here. Kolding Universitetsparken 1, 6000 Kolding Odense Campusvej 55, 5230 Odense M Esbjerg (Main campus) Niels Bohrs Vej 9-10, 6700 Esbjerg Slagelse Sdr. Stationsvej 28, 4200 Slagelse Sønderborg (Currently no Alsion 2, exchange available) 6400 Sønderborg Tel: +45 6550 2264 · Email: [email protected] · www.sdu.dk Facebook.com/SDUInternational & Facebook.com/unisouthdenmark 3 | Exchange Student Guide Why? Become an Exchange Student ................................. 7 Denmark..................................................... 8 Join the Erasmus Student Network.............................12 University of Southern Denmark.............................. 14 Study in - Odense........................................... 19 - Sønderborg........................................21 - Slagelse............................................23 - Kolding............................................25 - Esbjerg ............................................27 What? Programmes offered ......................................... 28 Useful information for Exchange Students.....................30 How? The process of becoming an Exchange student .................32 5 | Exchange Student Guide Velkommen... This guide is intended for people who enjoy -

Karlstad University Address: Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88

Application Process For a student being able to apply, our partner universities first must nominate their students online on Moveonnet. Information about this is sent to all partner universities before the deadline. When the student has been nominated instructions on how and where to apply will be sent directly to the student, with a copy to the coordinator. Nomination & Application Course Application Deadlines Karlstad University 15th April for Semester 1 or Full Year applicants 15th October for Semester 2 applicants Address: Universitetsgatan 2, 651 88 Karlstad, Main Web Address: http://www.kau.se/en Language of Study University Introduction For courses taught in English, a good knowledge of English is required CEFR B2. Non-native speakers of As one of the youngest universities in Sweden, we English may be required to prove their knowledge hope to be more adventurous in challenging the of English. established and exploring the unknown. Karlstad University offers Swedish language courses for exchange students. The courses provide some Our ambition is to contribute to the development of practical skills in the Swedish language as well as a knowledge at international, regional and individual brief survey of Swedish society and Swedish culture. levels. Thanks to our openness, creativity and multi- disciplinary approach, we have already attained a Course Catalogue: Exchange Students Courses significant level of academic achievement. All our Credits education and research is underpinned by a close dialogue with private companies and public Modules are credited in ECTS (European Credit organisations. We can also offer one of the most Transfer System). The ECTS protocol allocates 60 inspirational university environments in the credits to a full academic year’s work, and 30 credits to a semester’s work. -

Austria Belgium Canada

We are pleased to provide you with some of the current job openings across the globe at AKATECH.tech, your network of careers in the field of Computer Science and Engineering. Austria • PREMIUM Professor in Geoenergy Production Engineering Montanuniversität Leoben - Leoben • PREMIUM Full Professor in Electrochemical Energy Conversion Montanuniversität Leoben - Leoben Belgium • Instructor position Photo-electrochemical catalysis & sensing University of Antwerp - Antwerpen • Postdoctoral researcher 'In vivo Cellular and Molecular imaging' KU Leuven - Brussels • Tenure Track Lecturer Mathematics/Continuous techniques in Data Science Vrije Universiteit Brussel - Ixelles • PhD Researcher in Linguistics and Artificial Intelligence KU Leuven - Leuven • Postdoc Position in Applied Artificial Intelligence and Software Engineering KU Leuven - Leuven • Post-doctoral assistant (18256) - Civil engineering Ghent University - Gent • Assistant - Department of Information Technology Ghent University - Gent • Assistant - Department of Electronics and Information Systems Foscari University of Venice - Gent Canada • Assistant Professor - Cybersecurity Curtin University - Vaughan • AI Research Chair in Artificial Intelligence and Logistics Dalhousie University - Halifax • Assistant Professor of Computer Science Dalhousie University - Halifax • Assistant Professor, Distributed Systems University of Calgary - Calgary • Tenured and Tenure-Track Faculty - Assistant Professor - Software Engineering Ontario Tech University - Oshawa • Assistant Professor - Applied