Pakistan, February 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDUS DELTA, PAKISTAN: Economic Costs of Reduction in Freshwater Flows

water allocationdecisions. factored intoriverbasinplanning,or benefits of water-basedecosystemsarerarely economic users ofwater.Yettheeconomic schemes, Pakistan’secosystems,too,are hydropower dams, reservoirs,irrigationand as water tolarge-scale,commercialusessuch imperative that favours theallocationof Contrary tothedominantdevelopment economically norecologicallyoptimal. decisions beingmadethatareneither needs has oftenledtowaterallocation Failure torecognisedownstreamecosystem heavily byupstreamwaterabstraction. end of rivers,havebeenimpactedmost the at lie and marineregions,becausethey Coastal ecosystems. needs ofdownstream many cases, left insufficientflowtomeetthe of large volumesofwaterfromrivershas,in particular there isconcernthattheabstraction exacting a heavytollontheenvironment.In This impressive irrigationsystemis,however, world. the irrigated torain-fedlandratioin highest the farmland, affordingPakistan system feedsmorethan15millionhectaresof than 1.65 million km(IRIN2001).The more watercourses witharunninglengthof 89,000 conveyance lengthof57,000km,and head works, 43maincanalswitha or barrages 19 three majorstoragereservoirs, comprises Pakistan’s vastirrigationnetwork Pakistan Water-based developmentsin flows reduction infreshwater economic costsof INDUS DELTA,PAKISTAN: VALUATION #5:May2003 CASE STUDIESINWETLAND Integrating Wetland Economic Values into River Basin Management Managing freshwater flows in the The economic costs and losses arising from Indus River such omissions can be immense, and often The Indus River has -

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods Of

water Review A Review on Silver Nanoparticles: Classification, Various Methods of Synthesis, and Their Potential Roles in Biomedical Applications and Water Treatment Muhammad Zahoor 1,* , Nausheen Nazir 1 , Muhammad Iftikhar 1, Sumaira Naz 1, Ivar Zekker 2,*, Juris Burlakovs 3 , Faheem Uddin 4, Abdul Waheed Kamran 5, Anna Kallistova 6, Nikolai Pimenov 6 and Farhat Ali Khan 7 1 Department of Biochemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] (N.N.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (S.N.) 2 Faculty of Science, Institute of Chemistry, University of Tartu, 51014 Tartu, Estonia 3 Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Estonian University of Life Sciences, 51006 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Engineering & Technology, Mardan 23200, Pakistan; [email protected] 5 Department of Chemistry, University of Malakand, Chakdara 18800, Pakistan; [email protected] 6 Research Centre of Biotechnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Winogradsky Institute of Microbiology, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (N.P.) 7 Department of Pharmacy, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal 18050, Pakistan; [email protected] Citation: Zahoor, M.; Nazir, N.; * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.Z.); [email protected] (I.Z.) Iftikhar, M.; Naz, S.; Zekker, I.; Burlakovs, J.; Uddin, F.; Kamran, A.W.; Kallistova, A.; Pimenov, N.; Abstract: Recent developments in nanoscience have appreciably modified how diseases are pre- et al. A Review on Silver vented, diagnosed, and treated. Metal nanoparticles, specifically silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), are Nanoparticles: Classification, Various widely used in bioscience. From time to time, various synthetic methods for the synthesis of AgNPs Methods of Synthesis, and Their are reported, i.e., physical, chemical, and photochemical ones. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017

National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform Government of Pakistan National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 Key messages from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Planning, Development and Reform and the Chief Ministers 2 of 40 DRAFT – for concurrence National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 Key messages from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Planning, Development and Reform and the Chief Ministers [Brief statements or messages from the Prime Minister, Minister of Planning, Development and Reform and the Chief Ministers to be added.] 3 of 40 DRAFT – for concurrence National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 4 of 40 DRAFT – for concurrence National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 Contents Introduction messages 2 1 The State of Pakistan’s Transport Sector 4 1.1 Pakistan’s Transport Context: The Current Situation 5 1.2 Business as Usual Scenario 10 2 The Need for a National Transport Policy and Master Plan 14 2.1 Contribution to the Pakistan’s Government Policies and Plans 15 2.2 Relationship with existing policies and transport plans 16 3 National Transport Vision for Pakistan 17 3.1 Vision Statement 17 4 Principles for the Governance of Pakistan’s Transport Sector 18 5 National Transport Policy Objectives 21 6 Policy directions for each of the transport sub-sectors 26 6.1 Road transport 27 6.2 Rail transport 28 6.3 Air transport 29 6.4 Maritime transport 30 6.5 Pipelines 31 6.6 Inland Waterway transport 31 6.7 Urban transport 32 6.8 Multimodal logistics 33 7 Implementation arrangements 34 8 Bibliography 37 5 of 40 DRAFT – for concurrence National Transport Policy of Pakistan 2017 1. -

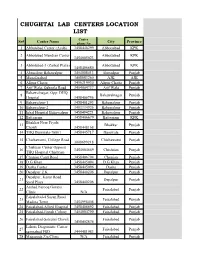

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics the Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES Count in the Politics of Every Country

(Established January 1949) September 28, 1957 Volume IX—No, 39 Price 50 Naye Paise EDITORIALS Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics The Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES count in the politics of every country. But in WEEKLY NOTES P Pakistan, politics seem to centre mainly around personalities. Thin Kandla Nearing Capacity- explains the frequent changes in party tactics and the policies of parties. Reassessment Necessary In such circumstances, as is only to be expected, political stability eludes —Pibul Goes — Welcome the country. It is tempting to draw a parallel between Pakistan and Rapprochement — P r o- Prance. There are some similarities in the underlying conditions in blem of Housing—Scarcity Pakistan and Indonesia. But there are limits beyond which such com of Material — U P's Tax parisons are misleading. Even as President Soekarno experiments with on Large Holdings Bank "guided democracy", President Iskander Mirza talks about "controlled Rate Change and India- democracy". But the Indonesian President's policy is based on an ideal Production of Radio Re whereas the Pakistani President's interference with the affairs of the ceivers 1247 State is solely justified on considerations of that country's integrity. LETTER TO THE EDITOR That also is the main, if not the only, binding force among parties and Chair-borne Critics 1250 politicians in Pakistan. A CALCUTTA DIARY Yet, experience and developing events make it increasingly evident Not by the Police Alone 1251 that Pakistan's march to progress cannot be ensured on such negative foundations as the country's integrity, annexation of Kashmir and the FROM THE LONDON END ever-present problem of maintaining a precarious balance between the Seven Per Cent and the country's two wings. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Survey of Ecotourism Potential in Pakistan's Biodiversity Project Area (Chitral and Northern Areas): Consultancy Report for IU

Survey of ecotourism potential in Pakistan’s biodiversity project area (Chitral and northern areas): Consultancy report for IUCN Pakistan John Mock and Kimberley O'Neil 1996 Keywords: conservation, development, biodiversity, ecotourism, trekking, environmental impacts, environmental degradation, deforestation, code of conduct, policies, Chitral, Pakistan. 1.0.0. Introduction In Pakistan, the National Tourism Policy and the National Conservation Strategy emphasize the crucial interdependence between tourism and the environment. Tourism has a significant impact upon the physical and social environment, while, at the same time, tourism's success depends on the continued well-being of the environment. Because the physical and social environment constitutes the resource base for tourism, tourism has a vested interest in conserving and strengthening this resource base. Hence, conserving and strengthening biodiversity can be said to hold the key to tourism's success. The interdependence between tourism and the environment is recognized worldwide. A recent survey by the Industry and Environment Office of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP/IE) shows that the resource most essential for the growth of tourism is the environment (UNEP 1995:7). Tourism is an environmentally-sensitive industry whose growth is dependent upon the quality of the environment. Tourism growth will cease when negative environmental effects diminish the tourism experience. By providing rural communities with the skills to manage the environment, the GEF/UNDP funded project "Maintaining Biodiversity in Pakistan with Rural Community Development" (Biodiversity Project), intends to involve local communities in tourism development. The Biodiversity Project also recognizes the potential need to involve private companies in the implementation of tourism plans (PC II:9).