Anuran Community in a Neotropical Natural Ecotone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anuran Community of a Cocoa Agroecosystem in Southeastern Brazil

SALAMANDRA 51(3) 259–262 30 October 2015 CorrespondenceISSN 0036–3375 Correspondence Anuran community of a cocoa agroecosystem in southeastern Brazil Rogério L. Teixeira1,2, Rodrigo B. Ferreira1,3, Thiago Silva-Soares4, Marcio M. Mageski5, Weslei Pertel6, Dennis Rödder7, Eduardo Hoffman de Barros1 & Jan O. Engler7 1) Ello Ambiental, Av. Getúlio Vargas, 500, Colatina, Espirito Santo, Brazil, CEP 29700-010 2) Laboratorio de Ecologia de Populações e Conservação, Universidade Vila Velha. Rua Comissário José Dantas de Melo, 21, Boa Vista, Vila Velha, ES, Brasil. CEP 29102-920 3) Instituto Nacional da Mata Atlântica, Laboratório de Zoologia, Avenida José Ruschi, no 04, Centro, CEP 29.650-000, Santa Teresa, Espírito Santo, Brazil 4) Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, Dept. Vertebrados, Lab. de Herpetologia, Rio de Janeiro, 20940-040, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 5) Universidade Vila Velha, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Ecossistemas, Rua Comissário José Dantas de Melo, 21, Vila Velha, 29102-770, Espírito Santo, Brazil 6) Instituto Estadual de Meio Ambiente e Recursos Hídricos – IEMA, Rodovia BR 262, Cariacica, 29140-500, Espírito Santo, Brazil 7) Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Division of Herpetology, Adenauerallee 160, 53113, Bonn, Germany Correspondence: Rodrigo B. Ferreira, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 21 July 2014 Accepted: 30 September 2014 by Stefan Lötters Brazil’s Atlantic Forest is considered a biodiversity ern Brazil. Fieldwork was carried out on approximately “hotspot” (Myers et al. 2000). Originally, this biome cov- 2,500 m² at the Fazenda José Pascoal (19°28’ S, 39°54’ W), ered ca. 1,350,000 km² along the east coast of Brazil (IBGE district of Regência, municipality of Linhares, state of Es- 1993). -

01-Marty 148.Indd

Copy proofs - 2-12-2013 Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. (2013) 148 : 419-424 On the occurrence of Dendropsophus leali (Bokermann, 1964) (Anura; Hylidae) in French Guiana by Christian MARTY (1)*, Michael LEBAILLY (2), Philippe GAUCHER (3), Olivier ToSTAIN (4), Maël DEWYNTER (5), Michel BLANC (6) & Antoine FOUQUET (3). (1) Impasse Jean Galot, 97354 Montjoly, Guyane française [email protected] (2) Health Center, 97316, Antécum Pata, Guyane française (3) CNRS Guyane USR 3456, Immeuble Le Relais, 2 avenue Gustave Charlery, 97300 Cayenne, Guyane française (4) Ecobios, BP 44, 97321, Cayenne CEDEX , Guyane française (5) Biotope, Agence Amazonie-Caraïbes, 30 domaine de Montabo, Lotissement Ribal, 97300 Cayenne, Guyane française (6) Pointe Maripa, RN2/PK35, Roura, Guyane française Summary – Dendropsophus leali is a small Amazonian tree frog occurring in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia where it mostly inhabits patches of open habitat and disturbed forest. We herein report five new records of this species from French Guiana extending its range 650 km to the north-east and sug- gesting that D. leali could be much more widely distributed in Amazonia than previously thought. The origin of such a disjunct distribution pattern probably lies in historical fluctuations of the forest cover during the late Tertiary and the Quaternary. Poor understanding of Amazonian species distribution still impedes comprehensive investigation of the processes that have shaped Amazonian megabiodiversity. Key-words: Dendropsophus leali, Anura, Hylidae, distribution, French Guiana. Résumé – À propos de la présence de Dendropsophus leali (Bokermann, 1964) (Anura ; Hylidae) en Guyane française. Dendropsophus leali est une rainette de petite taille présente au Brésil, au Pérou, en Bolivie et en Colombie où elle occupe principalement des habitats ouverts ou des forêts perturbées. -

Ecotone Properties and Influences on Fish Distributions Along Habitat Gradients of Complex Aquatic Systems

ECOTONE PROPERTIES AND INFLUENCES ON FISH DISTRIBUTIONS ALONG HABITAT GRADIENTS OF COMPLEX AQUATIC SYSTEMS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nuanchan Singkran May 2007 © 2007 Nuanchan Singkran ECOTONE PROPERTIES AND INFLUENCES ON FISH DISTRIBUTIONS ALONG HABITAT GRADIENTS OF COMPLEX AQUATIC SYSTEMS Nuanchan Singkran, Ph. D. Cornell University 2007 Ecotone properties (formation and function) were studied in complex aquatic systems in New York State. Ecotone formations were detected on two embayment- stream gradients associated with Lake Ontario during June–August 2002, using abrupt changes in habitat variables and fish species compositions. The study was repeated at a finer scale along the second gradient during June–August 2004. Abrupt changes in the habitat variables (water depth, current velocity, substrates, and covers) and peak species turnover rate showed strong congruence at the same location on one gradient. The repeated study on the second gradient in the summer of 2004 confirmed the same ecotone orientation as that detected in the summer of 2002 and revealed the ecotone width covering the lentic-lotic transitions. The ecotone on the second gradient acted as a hard barrier for most of the fish species. Ecotone properties were determined along the Hudson River estuary gradient during 1974–2001 using the same methods employed in the freshwater system. The Hudson ecotones showed both changes in location and structural formation over time. Influences of tide, freshwater flow, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and water temperature tended to govern ecotone properties. One ecotone detected in the lower-middle gradient portion appeared to be the optimal zone for fish assemblages, but the other ecotones acted as barriers for most fish species. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Comportamendo Animal.Indd

Valeska Regina Reque Ruiz (Organizadora) Comportamento Animal Atena Editora 2019 2019 by Atena Editora Copyright da Atena Editora Editora Chefe: Profª Drª Antonella Carvalho de Oliveira Diagramação e Edição de Arte: Geraldo Alves e Lorena Prestes Revisão: Os autores Conselho Editorial Prof. Dr. Alan Mario Zuffo – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul Prof. Dr. Álvaro Augusto de Borba Barreto – Universidade Federal de Pelotas Prof. Dr. Antonio Carlos Frasson – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Prof. Dr. Antonio Isidro-Filho – Universidade de Brasília Profª Drª Cristina Gaio – Universidade de Lisboa Prof. Dr. Constantino Ribeiro de Oliveira Junior – Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa Profª Drª Daiane Garabeli Trojan – Universidade Norte do Paraná Prof. Dr. Darllan Collins da Cunha e Silva – Universidade Estadual Paulista Profª Drª Deusilene Souza Vieira Dall’Acqua – Universidade Federal de Rondônia Prof. Dr. Eloi Rufato Junior – Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Prof. Dr. Fábio Steiner – Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso do Sul Prof. Dr. Gianfábio Pimentel Franco – Universidade Federal de Santa Maria Prof. Dr. Gilmei Fleck – Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná Profª Drª Girlene Santos de Souza – Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia Profª Drª Ivone Goulart Lopes – Istituto Internazionele delle Figlie de Maria Ausiliatrice Profª Drª Juliane Sant’Ana Bento – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Prof. Dr. Julio Candido de Meirelles Junior – Universidade Federal Fluminense Prof. Dr. Jorge González Aguilera – Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul Profª Drª Lina Maria Gonçalves – Universidade Federal do Tocantins Profª Drª Natiéli Piovesan – Instituto Federal do Rio Grande do Norte Profª Drª Paola Andressa Scortegagna – Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa Profª Drª Raissa Rachel Salustriano da Silva Matos – Universidade Federal do Maranhão Prof. -

High Species Turnover Shapes Anuran Community Composition in Ponds Along an Urban-Rural Gradient

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.01.276378; this version posted September 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. 1 High species turnover shapes anuran community composition in ponds along an urban-rural 2 gradient 3 4 Carolina Cunha Ganci1*, Diogo B. Provete2,3, Thomas Püttker4, David Lindenmayer5, 5 Mauricio Almeida-Gomes2 6 7 1 Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, 8 Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, 79002-970, Brazil. 9 2 Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato 10 Grosso do Sul, 79002-970, Brazil. 11 3 Göthenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Göteborg, SE-450, Sweden. 12 4 Departamento de Ciências Ambientais, Universidade Federal de São Paulo - UNIFESP, São 13 Paulo, 09913-030, Brazil. 14 5 Fenner School of Environment and Societ, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 15 Australia. 16 17 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 18 19 Carolina Ganci orcid: 0000-0001-7594-8056 20 Diogo B. Provete orcid: 0000-0002-0097-0651 21 Thomas Püttker orcid: 0000-0003-0605-1442 22 Mauricio Almeida-Gomes orcid: 0000-0001-7938-354X 23 David Lindenmayer orcid: 0000-0002-4766-4088 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.01.276378; this version posted September 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Species Delimitation, Patterns of Diversification and Historical Biogeography of the Neotropical Frog Genus Adenomera

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2014) 41, 855–870 ORIGINAL Species delimitation, patterns of ARTICLE diversification and historical biogeography of the Neotropical frog genus Adenomera (Anura, Leptodactylidae) Antoine Fouquet1,2*, Carla Santana Cassini3,Celio Fernando Baptista Haddad3, Nicolas Pech4 and Miguel Trefaut Rodrigues2 1CNRS Guyane USR3456, 97300 Cayenne, ABSTRACT French Guiana, 2Departamento de Zoologia, Aim For many taxa, inaccuracy of species boundaries and distributions Instituto de Bioci^encias, Universidade de S~ao hampers inferences about diversity and evolution. This is particularly true in Paulo, CEP 05508-090 S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil, 3Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de the Neotropics where prevalence of cryptic species has often been demon- Bioci^encias, Universidade Estadual Paulista strated. The frog genus Adenomera is suspected to harbour many more species Julio de Mesquita Filho, CEP 13506-900 Rio than the 16 currently recognized. These small terrestrial species occur in Claro, SP, Brazil, 4Aix-Marseille Universite, Amazonia, Atlantic Forest (AF), and in the open formations of the Dry Diagonal CNRS, IRD, UMR 7263 – IMBE, Evolution (DD: Chaco, Cerrado and Caatinga). This widespread and taxonomically com- Genome Environnement, 13331 Marseille plex taxon provides a good opportunity to (1) test species boundaries, and (2) Cedex 3, France investigate historical connectivity between Amazonia and the AF and associated patterns of diversification. Location Tropical South America east of the Andes. Methods We used molecular data (four loci) to estimate phylogenetic rela- tionships among 320 Adenomera samples. These results were integrated with other lines of evidence to propose a conservative species delineation. We subse- quently used an extended dataset (seven loci) and investigated ancestral area distributions, dispersal–vicariance events, and the temporal pattern of diversifi- cation within Adenomera. -

For Review Only

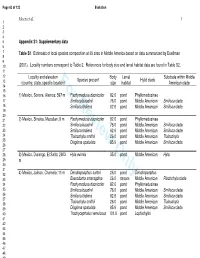

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Cohabitation by Bothrops Asper (Garman 1883) and Leptodactylus Savagei (Heyer 2005)

Herpetology Notes, volume 12: 969-970 (2019) (published online on 10 October 2019) Cohabitation by Bothrops asper (Garman 1883) and Leptodactylus savagei (Heyer 2005) Todd R. Lewis1 and Rowland Griffin2 Bothrops asper is one of the largest (up to 245 cm) log-pile habitat (approximately 50 x 70 x 100cm) during pit vipers in Central America (Hardy, 1994; Rojas day and night. Two adults (with distinguishable size et al., 1997; Campbell and Lamar, 2004). Its range and markings) appeared resident with multiple counts extends from northern Mexico to the Pacific Lowlands (>20). Adults of B. asper were identified individually of Ecuador. In Costa Rica it is found predominantly in by approximate size, markings, and position on the log- Atlantic Lowland Wet forests. Leptodactylus savagei, pile. The above two adults were encountered on multiple a large (up to 180 mm females: 170 mm males snout- occasions between November 2002 and December vent length [SVL]), nocturnal, ground-dwelling anuran, 2003 and both used the same single escape hole when is found in both Pacific and Atlantic rainforests from disturbed during the day. Honduras into Colombia (Heyer, 2005). Across their On 20 November 2002, two nights after first locating ranges, both species probably originated from old forest and observing the above two Bothrops asper, a large but now are also found in secondary forest, agricultural, (131mm SVL) adult Leptodactylus savagei was seen disturbed and human inhabited land (McCranie and less than 2m from two coiled pit vipers (23:00 PM local Wilson, 2002; Savage, 2002; Sasa et al., 2009). Such time). When disturbed, it retreated into the same hole the habitat adaptation is most likely aided by tolerance for a adult pit vipers previously escaped to in the daytime. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Effects of Beaver Dams on Benthic Macroinvertebrates

Effects ofbeaver dams onbenthic macroinvertebrates Andreas Johansson Degree project inbiology, Master ofscience (2years), 2014 Examensarbete ibiologi 45 hp tillmasterexamen, 2014 Biology Education Centre, Uppsala University, and Department ofAquatic Sciences and Assessment, SLU Supervisor: Frauke Ecke External opponent: Peter Halvarsson ABSTRACT In the 1870's the beaver (Castor fiber), population in Sweden had been exterminated. The beaver was reintroduced to Sweden from the Norwegian population between 1922 and 1939. Today the population has recovered and it is estimated that the population of C. fiber in all of Europe today ranges around 639,000 individuals. The main aim with this study was to investigate if there was any difference in species diversity between sites located upstream and downstream of beaver ponds. I found no significant difference in species diversity between these sites and the geographical location of the streams did not affect the species diversity. This means that in future studies it is possible to consider all streams to be replicates despite of geographical location. The pond age and size did on the other hand affect the species diversity. Young ponds had a significantly higher diversity compared to medium-aged ponds. Small ponds had a significantly higher diversity compared to medium-sized and large ponds. The upstream and downstream reaches did not differ in terms of CPOM amount but some water chemistry variables did differ between them. For the functional feeding groups I only found a difference between the sites for predators, which were more abundant downstream of the ponds. SAMMANFATTNING Under 1870-talet utrotades den svenska populationen av bäver (Castor fiber). -

New Record of Corythomantis Greeningi Boulenger, 1896 (Amphibia, Hylidae) in the Cerrado Domain, State of Tocantins, Central Brazil

Herpetology Notes, volume 7: 717-720 (2014) (published online on 21 December 2014) New record of Corythomantis greeningi Boulenger, 1896 (Amphibia, Hylidae) in the Cerrado domain, state of Tocantins, Central Brazil Leandro Alves da Silva1,*, Mauro Celso Hoffmann2 and Diego José Santana3 Corythomantis greeningi is a hylid frog distributed Caatinga. This new record extends the distribution of along xeric and subhumid regions of northeastern Corythomantis greeningi around 160 km western from Brazil, usually associated with the Caatinga domain the EESGT, which means approximately 400 km from (Jared et al., 1999). However, recent studies have shown the edge of the Caatinga domain (Figure 1). Although a larger distribution for the species in the Caatinga and Corythomantis greeningi has already been registered Cerrado (Valdujo et al., 2011; Pombal et al., 2012; in the Cerrado, this record shows a wider distribution Godinho et al., 2013) (Table 1; Figure 1). This casque- into this formation, not only marginally as previously headed frog is a medium-sized hylid, with a pronounced suggested (Valdujo et al., 2012). This is the most western ossification in the head and high intraspecific variation record of Corythomantis greeningi. in skin coloration (Andrade and Abe, 1997; Jared et al., Quaternary climatic oscillations have modeled 2005). Herein, we report a new record of Corythomantis the distribution of South American open vegetation greeningi in the Cerrado and provide its distribution map formations (Caatinga, Cerrado and Chaco) (Werneck, based