The Dynamics of Faroese-Danish Language Contact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Spoken Danish Less Intelligible Than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J

Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly To cite this version: Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly. Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish?. Speech Communication, Elsevier : North-Holland, 2010, 52 (11-12), pp.1022. 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005. hal-00698848 HAL Id: hal-00698848 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00698848 Submitted on 18 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish? Charlotte Gooskens, Vincent J. van Heuven, Renée van Bezooijen, Jos J.A. Pacilly PII: S0167-6393(10)00109-3 DOI: 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005 Reference: SPECOM 1901 To appear in: Speech Communication Received Date: 3 August 2009 Revised Date: 31 May 2010 Accepted Date: 11 June 2010 Please cite this article as: Gooskens, C., van Heuven, V.J., van Bezooijen, R., Pacilly, J.J.A., Is spoken Danish less intelligible than Swedish?, Speech Communication (2010), doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2010.06.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

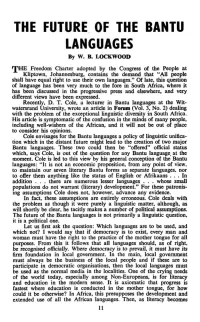

THE FUTURE of the BANTU LANGUAGES by W

THE FUTURE OF THE BANTU LANGUAGES By W. B. LOCKWOOD T^HE Freedom Charter adopted by the Congress of the People at Kliptown, Johannesburg, contains the demand that "All people shall have equal right to use their own languages." Of latef this question of language has been very much to the fore in South Africa, where it has been discussed in the progressive press and elsewhere, and very different views have been expressed. Recently, D. T. Cole, a lecturer in Bantu languages at the Wit- watersrand University, wrote an article in Forum (Vol. 3, No. 2) dealing with the problem of the exceptional linguistic diversity in South Africa. His article is symptomatic of the confusion in the minds of many people, including well-wishers of the African, and it will not be out of place to consider his opinions. Cole envisages for the Bantu languages a policy of linguistic unifica tion which in the distant future might lead to the creation of two major Bantu languages. These two could then be "offered" official status which, says Cole, is out of the question for any Bantu language, at the moment. Cole is led to this view by his general conception of the Bantu languages: "It is not an economic proposition, from any point of view, to maintain our seven literary Bantu forms as separate languages, nor to offer them anything like the status of English or Afrikaans ... In addition . there are numerous lesser languages . whose small populations do not warrant (literary) development." For these patronis ing assumptions Cole does not, however, advance any evidence. -

Sixth Periodical Report Presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in Accordance with Article 15 of the Charter

Strasbourg, 19 February 2018 MIN-LANG (2018) PR 1 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Sixth periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter GERMANY Sixth Report of the Federal Republic of Germany pursuant to Article 15 (1) of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages 2017 3 Table of contents A. PRELIMINARY REMARKS ................................................................................................................8 B. UPDATED GEOGRAPHIC AND DEMOGRAPHIC INFORMATION ...............................................9 C. GENERAL TRENDS..........................................................................................................................10 I. CHANGED FRAMEWORK CONDITIONS......................................................................................................10 II. LANGUAGE CONFERENCE, NOVEMBER 2014 .........................................................................................14 III. DEBATE ON THE CHARTER LANGUAGES IN THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG, JUNE 2017..............................14 IV. ANNUAL IMPLEMENTATION CONFERENCE ...............................................................................................15 V. INSTITUTE FOR THE LOW GERMAN LANGUAGE, FEDERAL COUNCIL FOR LOW GERMAN ......................15 VI. BROCHURE OF THE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF THE INTERIOR ....................................................................19 VII. LOW GERMAN IN BRANDENBURG.......................................................................................................19 -

Self-Determination and Sub-Sovereign Statehood in the EU with Particular Reference to Scotland and Passing Reference to the Faroe Islands L

Alasdair Geater and Scott Crosbyt Self-determination and Sub-sovereign Statehood in the EU with particular reference to Scotland and passing reference to the Faroe Islands l. Points of Departure II. Fear of Freedom III. Self-Determination as a Fundamental Human Right IV. Arguments of Dissuasion and their Rebuttal On the perceived dangers of nationafis m On the perceived risk of economic isolation On the fe ar of fragmentation IV. The Exercise of the Right of Self-determination under EU Law VI. The Importance of History VII. The Particular Case of Scotland Historical Constitutional Consequences of Scottish Statehood The Process The benefits of statehood ? 1 Partners respectively in Geater and Co and Stanbrook & Hooper, Brussels and faunding partners of Geater & Crosby, a joint venture devoted to Scots constitutional law, also based in Brussels. The seeds for this discourse were sown in a leeture in 1975 by Professor Neil MacCormick, then ayoung Dean of the Faculty of Law at Edinburgh University, which the younger of the co authors attended (and remembered). Føroyskt L6gar Rit (Faroese Law Review) vol. 1 no. 1 - 2001 "In a united Europe every small country can find its place alongside the former great powers" 2 Føroyskt Urtak Heiti: Sjalvsavgeroarrættur og at vera statur f ES viiJ partvisum fullveldi, vio serligum atliti til Skotlands, men eisini vio atliti til Føroya. Greinin vioger [ heimspekiligum og politiskum høpi tjdningin av, at tj6oir, sum nu eru i felagskapi viiJ aorar i ES, faa fullveldi og egnan ES-limaskap. Høvundarnir halda uppa, at tao er 6missandi rættur f fullum samsvari vio ES-Sattmalan hja hesum tj6oum at faa egnan ES-limaskap. -

The Position of Frisian in the Germanic Language Area Charlotte

The Position of Frisian in the Germanic Language Area Charlotte Gooskens and Wilbert Heeringa 1. Introduction Among the Germanic varieties the Frisian varieties in the Dutch province of Friesland have their own position. The Frisians are proud of their language and more than 350,000 inhabitants of the province of Friesland speak Frisian every day. Heeringa (2004) shows that among the dialects in the Dutch language area the Frisian varieties are most distant with respect to standard Dutch. This may justify the fact that Frisian is recognized as a second official language in the Netherlands. In addition to Frisian, in some towns and on some islands a mixed variety is used which is an intermediate form between Frisian and Dutch. The variety spoken in the Frisian towns is known as Town Frisian1. The Frisian language has existed for more than 2000 years. Genetically the Frisian dialects are most closely related to the English language. However, historical events have caused the English and the Frisian language to diverge, while Dutch and Frisian have converged. The linguistic distance to the other Germanic languages has also altered in the course of history due to different degrees of linguistic contact. As a result traditional genetic trees do not give an up-to-date representation of the distance between the modern Germanic languages. In the present investigation we measured linguistic distances between Frisian and the other Germanic languages in order to get an impression of the effect of genetic relationship and language contact for the position of the modern Frisian language on the Germanic language map. -

What Can Faroese Pseudocoordination Tell Us About English Inflection?

What can Faroese pseudocoordination tell us about English inflection? Daniel Ross University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1 Introduction English, with its relatively impoverished morphology within Germanic, offers no evidence for determining whether a given verb form is inflected identically to the lexical root or not inflected at all. Furthermore, it is unclear whether all such identical forms are accidentally homophonous or are indications of systematic syncretism that is part of the mechanics of the morphosyntax of the language. This article addresses a particular morphosyntactic phenomenon for which this distinction has greater implications for the grammar. Does the grammar allow for specific requirements of uninflected verbal forms in certain constructions? Are uninflected present-tense forms of the verb systematically equivalent to the infinitive in a way that is operational in the grammar? Specifically, the ban on inflection found in English try and pseudocoordination is investigated in detail. As shown in (1), the construction is permitted if and only if both verbs happen to be in their uninflected forms.1 (1) a. Try and win the race! [Then even if you do not succeed, you tried.] b. I will try and win the race [but I am tired and might not be able to win]. c. I try and win the race every time [even though I rarely succeed]. d. *He tries and win(s) the race every time [but he rarely succeeds]. e. He did try and win the race [but his injury made it impossible]. f. *He tried and win/won the race [but his injury made it impossible]. -

Different Paths Towards Autonomy

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Sagnfræði Different paths towards autonomy: A comparison of the political status of the Faroe Islands and th Iceland in the first half of the 19 century Ritgerð til B. A.- prófs Regin Winther Poulsen Kt.: 111094-3579 Leiðbeinandi: Anna Agnarsdóttir Janúar 2018 Abstract This dissertation is a comparison of the political status of Iceland and the Faroe Islands within the Danish kingdom during the first half of the 19th century. Though they share a common history, the two dependencies took a radically different path towards autonomy during this period. Today Iceland is a republic while the Faroes still are a part of the Danish kingdom. This study examines the difference between the agendas of the two Danish dependencies in the Rigsdagen, the first Danish legislature, when it met for the first time in 1848 to discuss the first Danish constitution, the so-called Junigrundloven. In order to explain why the political agendas of the dependencies were so different, it is necessary to study in detail the years before 1848. The administration, trade and culture of the two dependencies are examined in order to provide the background for the discussion of the quite different political status Iceland and the Faroes had within the Danish kingdom. Furthermore, the debates in the Danish state assemblies regarding the re-establishment of the Alþingi in 1843 are discussed in comparison to the debates in the same assemblies regarding the re-establishment of the Løgting in 1844 and 1846. Even though the state assemblies received similar petitions from both dependencies, Alþingi was re-established in 1843, while the same did not happen with the Løgting in the Faroes. -

An Update and Extension of the META-NET Study “Europe’S Languages in the Digital Age”

An Update and Extension of the META-NET Study “Europe’s Languages in the Digital Age” Georg Rehm1, Hans Uszkoreit1, Ido Dagan2, Vartkes Goetcherian3, Mehmet Ugur Dogan4, Coskun Mermer4, Tamás Varadi5, Sabine Kirchmeier-Andersen6, Gerhard Stickel7, Meirion Prys Jones8, Stefan Oeter9, Sigve Gramstad10 META-NET META-NET META-NET META-NET DFKI GmbH Bar-Ilan University Arax Ltd. Tübitak Bilgem Berlin, Germany1 Tel Aviv, Israel2 Luxembourg3 Gebze, Turkey4 EFNIL, META-NET EFNIL, META-NET EFNIL NPLD Hungarian Academy of Sciences Danish Language Council Institut für Deutsche Sprache Network to Promote Ling. Diversity Budapest, Hungary5 Copenhagen, Denmark6 Mannheim, Germany7 Cardiff, Wales8 Council of Europe, Com. of Experts Council of Europe, Com. of Experts University of Hamburg Bergen, Norway10 Hamburg, Germany9 Abstract This paper extends and updates the cross-language comparison of LT support for 30 European languages as published in the META-NET Language White Paper Series. The updated comparison confirms the original results and paints an alarming picture: it demonstrates that there are even more dramatic differences in LT support between the European languages. Keywords: LR National/International Projects, Infrastructural/Policy Issues, Multilinguality, Machine Translation 1. Introduction and Overview This paper extends and updates one important result of the work carried out within the META-VISION pillar The multilingual setup of our European society im- of the initiative, the cross-language comparison of LT poses societal challenges on political, economic and support for 30 European languages as published in the social integration and inclusion, especially in the cre- META-NET Language White Paper Series (Rehm and ation of the single digital market and unified informa- Uszkoreit, 2012). -

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue?

Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community NORD: 2012:008 ISBN: 978-92-893-2404-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/Nord2012-008 Author: Karin Arvidsson Editor: Jesper Schou-Knudsen Research and editing: Arvidsson Kultur & Kommunikation AB Translation: Leslie Walke (Translation of Bodil Aurstad’s article by Anne-Margaret Bressendorff) Photography: Johannes Jansson (Photo of Fredrik Lindström by Magnus Fröderberg) Design: Mar Mar Co. Print: Scanprint A/S, Viby Edition of 1000 Printed in Denmark Nordic Council Nordic Council of Ministers Ved Stranden 18 Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K DK-1061 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 www.norden.org The Nordic Co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involving Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. Nordic co-operation has firm traditions in politics, the economy, and culture. It plays an important role in European and international collaboration, and aims at creating a strong Nordic community in a strong Europe. Nordic co-operation seeks to safeguard Nordic and regional interests and principles in the global community. Common Nordic values help the region solidify its position as one of the world’s most innovative and competitive. Does the Nordic Region Speak with a FORKED Tongue? The Queen of Denmark, the Government Minister and others give their views on the Nordic language community KARIN ARVIDSSON Preface Languages in the Nordic Region 13 Fredrik Lindström Language researcher, comedian and and presenter on Swedish television. -

Hiking, Guided Walks, Visit Tórshavn FO-645 Æðuvík, Tel

FREE COPY TOURIST GUIDE 2018 www.visitfaroeislands.com #faroeislands Download the free app FAROE ISLANDS TOURIST GUIDE propellos.dk EXPERIENCE UP CLOSE We make it easy: Let 62°N lead the way to make the best of your stay on the Faroe Islands - we take care of practical arrangements too. We assure an enjoyable stay. Let us fly you to the Faroe Islands - the world’s most desireable island community*) » Flight Photo: Joshua Cowan - @joshzoo Photo: Daniel Casson - @dpc_photography Photo: Joshua Cowan - @joshzoo » Hotel » Car rental REYKJAVÍK » Self-catering FAROE ISLANDS BERGEN We fly up to three times daily throughout the year » Excursions directly from Copenhagen, and several weekly AALBORG COPENHAGEN EDINBURGH BILLUND » Package tours flights from Billund, Bergen, Reykjavik and » Guided tours Edinburgh - directly to the Faroe Islands. In the summer also from Aalborg, Barcelona, » Activity tours Book Mallorca, Lisbon and Crete - directly to the » Group tours your trip: Faroe Islands. BARCELONA Read more and book your trip on www.atlantic.fo MALLORCA 62n.fo LISBON CRETE *) Chosen by National Geographic Traveller. GRAN CANARIA Atlantic Airways Vága Floghavn 380 Sørvágur Faroe Islands Tel +298 34 10 00 PR02613-62N-A5+3mmBleed-EN-01.indd 1 31/05/2017 11.40 Explanation of symbols: Alcohol Store Airport Welcome to the Faroe Islands ................................................................................. 6 Aquarium THE ADVENTURE ATM What to do .................................................................................................................. -

Danish University Lecturers' Attitudes Towards English As the Medium of Instruction Ibérica, Núm

Ibérica ISSN: 1139-7241 [email protected] Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos España Jensen, Christian; Thøgersen, Jacob Danish University lecturers' attitudes towards English as the medium of instruction Ibérica, núm. 22, 2011, pp. 13-33 Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos Cádiz, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287023888002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 01 IBERICA 22.qxp:Iberica 13 21/09/11 16:59 Página 13 Danish University lecturers’ attitudes towards English as the medium of instruction Christian Jensen and Jacob Thøgersen University of Copenhagen (Denmark) [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract The increasing use of English in research and higher education has been the subject of heated debate in Denmark and other European countries over the last years. This paper sets out the various positions in the national debate in Denmark, and then examines the attitudes towards these positions among the teaching staff at the country’s largest university. Four topics are extracted from the debate – one which expresses a positive attitude towards English and three independent but interrelated topics which express more negative attitudes. The responses from the university lecturers show that a majority agree with all positions, negative as well as positive. This finding indicates that the attitude may not form a simple one-dimensional dichotomy. The responses are broken down according to lecturer age and the proportion of teaching the lecturer conducts in English.