Written Evidence from INQUEST (RHR0024)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Independent Review of Deaths and Serious Incidents in Police Custody

Report of the Independent Review of Deaths and Serious Incidents in Police Custody Rt. Hon. Dame Elish Angiolini DBE QC January 2017 Contents Acknowledgments 5 Executive Summary 7 Background 7 Key findings 7 Guarding the Vulnerable 14 1. Introduction 21 Background 21 Terms of Reference 22 Families 23 Previous reports 23 Other Ongoing Reviews and Action 24 The Legal Framework 25 Trends in deaths in police custody and suicides following police custody 26 Summary 28 2. Restraint 31 Introduction 31 Mental Health and restraint 33 Positional asphyxia 35 Training 36 Length of prone restraint 37 Excited Delirium/Acute Behavioural Disturbance 38 Struggle and restraint 40 The safety officer approach 41 Alternatives to manual force 42 Transportation in police vehicles 45 Recording of police use of force 46 3. Intoxication 51 Introduction 51 Observation regimes 51 ‘Drying out’ Centres 55 Denial of healthcare to intoxicated detainees 57 Alcohol withdrawal 59 Training on intoxication 59 4. Mental Health 63 Introduction 63 Modern policing and mental health 67 The inappropriateness of police custody 68 | 1 Mental health training 69 Removing mentally ill people from the policing context 70 Arresting for criminal offences rather than section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983 71 Detention under section 136 in the police station as a ‘place of safety’ 72 Liaison and Diversion Schemes 75 Avoiding detention under section 136 Mental Health Act 1983 76 Use of police officers to conduct restraint within mental health detention settings 77 5. Ethnicity 83 Introduction 83 Race and the investigative process 85 Stereotypical assumptions 87 Statistics on ethnicity 89 Accountability 91 6. -

Masks: the Big Question Iron-Age Murder Mystery

thevictorybugle Masks: The Big Question JULY 2020 ISSUE IX RUBY, YEAR 9—CURRENT AFFAIRS REPORTER For promotions and contributions: HOW WOULD THE PUBLIC Victorybugle REACT TO WEARING MASKS @ormistonvictoryacademy.co.uk IN PUBLIC BEING MADE COMPULSORY? The Bugle’s Statement: 1) The contemplation of safety. Our commitment to an B) The contemplation of respect. inclusive, entertaining and C) The contemplation of the environment. informative newsletter is what Also yes the 1,B&C was intentional. drives the contributors of this and do whatever they can get away with. publication. If you have any 1) Would it be safer to wear a mask as a Through this lockdown, have you seen comments or suggestions, groups of people doing activities together compulsory rule, or is social distancing contact us and we’ll address enough? who obviously aren’t from the same household? These people still have to get you issues as quickly as we can. We can only publish if you Logistically, yes, it would be safer but essential items, who’s to say they wouldn’t carry on with a careless attitude? politically, no, as the number of daily cases is still going down with the correct amount of C) The environment would suffer with the Follow us people doing what they’re doing. @victoryacad sudden amount of waste. Paper masks are a one-use product. B) Would people actually obey this as a rule and try to enter places anyway? Too many questions I know, enjoy the Personally, I would say yes, people will try potential sleep deprivation. Iron-Age Murder Mystery CITY’S FINAL FIXTURES MAISIE, YEAR 9—ENVIRONMENTAL REPORTER On the 11th of July, the skeleton of an iron age man was Norwich City v discovered in Buckinghamshire, near London. -

INQUEST Evidence Submission to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on “Systemic Racism, Violations Of

INQUEST evidence submission to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights report on “systemic racism, violations of international human rights law against Africans and people of African descent by law enforcement agencies, especially those incidents that resulted in the death of George Floyd and other Africans and people of African descent, to contribute to accountability and redress for victims” December 2020 Introduction 1. INQUEST Charitable Trust is an independent non-governmental organisation which provides expertise on state-related deaths and their investigation to bereaved people, lawyers, advice and support agencies, the media and parliamentarians. Our policy, parliamentary, campaigning and media work is grounded in the day to day experience of working with bereaved people. 2. Our specialist casework with bereaved families focuses on deaths in police and prison custody, immigration detention, mental health settings and deaths involving multi- agency failings or where wider issues of state and corporate accountability are in question, such as Hillsborough and the Grenfell Tower fire. INQUEST works primarily in England and Wales, and advises on a small number of cases in Scotland. We have also shared our expertise on the investigation of state related deaths and the treatment of bereaved people at an international level. 3. Over the past 40 years, INQUEST has advised and assisted countless bereaved families, including many families bereaved by deaths in contact with the police. As a result, we have a unique overview of the investigatory processes, the treatment of bereaved people and the issues arising from these deaths. We have worked consistently to strengthen the institutional framework for accountability for deaths in all forms of state detention and how this works in pursuit of goals of truth, justice and accountability for bereaved families. -

2018-04-25 Conducting Effective Voir Dire on Issues of Race Handouts

CLE SEMINAR Conducting Effective Voir Dire on Issues of Race Hosted at: Federal Public Defender's Office Speaker: Kyana Givens, AFPD from the Western District of Washington Portland, Oregon Live on April 25, 2018 12:00pm to 1:00pm Eugene, Oregon Via video conference on April 25, 2018 12:00pm to 1:00pm Medford, Oregon Via video conference on April 25, 2018 12:00pm to 1:00pm Bias in Blue: Instructing Jurors to Consider the Testimony of Police Officer Witnesses with Caution Vida B. Johnson* Abstract Jurors in criminal trials are instructed by the judge that they are to treat the testimony of a police officer just like the testimony of any other witness. Fact-finders are told that they should not give police officer testimony greater or lesser weight than any other witness they will hear from at trial. Jurors are to accept that police are no more believable or less believable than anyone else. Jury instructions regarding police officer testimony stand in contrast to the instructions given to jurors when a witness with a legally recognized interest in the outcome of the case has testified. In cases where witnesses have received financial assistance or plea deals for their testimony, a special instruction is given. For example, when a witness with a cooperation agreement testifies, the trial court will tell the jury that while the witness has the same obligation to tell the truth as other witnesses, the jury can consider whether the witness has an interest different from other types of witnesses and that her testimony should be considered with caution. -

An Evaluation of the Systems for Handling Police Complaints in Thailand

AN EVALUATION OF THE SYSTEMS FOR HANDLING POLICE COMPLAINTS IN THAILAND by DHIYATHAD PRATEEPPORNNARONG A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY College of Arts and Law School of Law University of Birmingham February 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis, based on empirical evidence and documentary analysis, critically evaluates the systems under the regulatory oversight of the Royal Thai Police (RTP), the Office of the Ombudsman, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and the National Anti- Corruption Commission (NACC) in respect of the handling of police complaints. Comparisons will be drawn from the system under the control of the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) in England and Wales in order to provide alternative perspectives to the Thai police complaints system. This thesis proposes a civilian control model of a police complaints system as a key reform measure to instill public confidence in the handling of complaints in Thailand. Additional measures ranging from sufficient power and resources, complainants‘ involvement, securing transparency and maintaining police faith in the system are also recommended to enhance the proposed system. -

'Inside Out' 660.Pdf

Miscarriages of JusticeUK (MOJUK) 22 Berners St, Birmingham B19 2DR to ask him/herself whether the sentencing court could conclude that the circumstances appli - Tele: 0121- 507 0844 Email: [email protected] Web: www.mojuk.org.uk cable when the sentence as passed had changed as a result of knowing failures by the assist - ing offender to give assistance in accordance with the assisting offender agreement?” MOJUK: Newsletter ‘Inside Out’ No 660 (02/11/2017) - Cost £1 Delivering the unanimous judgment of the Court, Lord Kerr stated “it is unquestionably true that in a number of instances, the judge found that the Stewarts had not been truthful”. Lord Supreme Court: DPP Correct in Deciding Not to Resentence Dishonest Witnesses Kerr found that the Court could not uphold the High Court’s view that “the predominant factor Seosamh Gráinséir for Irish Legal News: The UK Supreme Court has allowed an appeal by in deciding where the interests of justice lay was whether a change in circumstances had the Director of Public Prosecutions against the finding of the High Court in Northern Ireland occurred between those which obtained at the time that the agreement with the specified pros - that the DPP’s decision not to remit dishonest witnesses for re-sentencing was contrary to the ecutor was made and the time at which consideration of whether to refer the case back to the interests of justice. Overturning the High Court's finding that the matter of sentencing should original sentencing court took place”. be remitted to the DPP for a fresh decision, Lord Brian Kerr was satisfied that the DPP con - Section 74(3) imposes no explicit constraint on how the specified prosecutor should approach ducted “a careful, perfectly legitimate investigation of the question of the interests of justice” the question of the interests of justice and it was Lord Kerr’s opinion that there was “no warrant and that her decision could not be impeached. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard Record of the Entire Day in PDF Format. PDF File, 0.99

Thursday Volume 663 25 July 2019 No. 337 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 25 July 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1415 25 JULY 2019 1416 Patrick Grady (Glasgow North) (SNP): The Minister House of Commons might be toasting the new Prime Minister, but I do wonder how much hot air is being generated and what contribution that will make to the net emissions target. Thursday 25 July 2019 The Scottish Government have committed to net zero by 2045, rather than the UK Government’s 2050 target. The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Is the UK not willing to match that level of ambition? PRAYERS Mr Goodwill: When it comes to hot air, pots and kettles spring to mind. I look forward to working with the Scottish [MR SPEAKER ] in the Chair Administration to achieve the target. This is not a party political issue. Every single part of this House wants to take action on climate change, and it is vital that we do Oral Answers to Questions so to deliver a cleaner and greener planet in the future. Colin Clark (Gordon) (Con): This is perfect weather ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS for barbecues and enjoying Scottish beef. Does the Minister agree that the beef industry is doing its bit to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from burping cows? The Secretary of State was asked— Climate Change Adaptation Mr Goodwill: Methane is a very potent greenhouse gas, but it is interesting to note that, unlike carbon 1. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Friday Volume 642 15 June 2018 No. 154 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Friday 15 June 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 1193 15 JUNE 2018 MentalHealthUnits(UseofForce)Bill 1194 (9) The Secretary of State must publish the report as soon House of Commons as practicable upon the conclusion of the proceedings or investigation.”—(Mr Reed.) Brought up, and read the First time. Friday 15 June 2018 9.35 am The House met at half-past Nine o’clock Mr Steve Reed (Croydon North) (Lab/Co-op): I beg PRAYERS to move, That the clause be read a Second time. Mr Speaker: With this it will be convenient to discuss [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] the following: 9.34 am New clause 2—Independent investigation of deaths: legal aid— Mr Steve Reed (Croydon North) (Lab/Co-op): I beg ‘(1) Schedule 1 to the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment to move, That the House sit in private. of Offenders Act 2012 (civil legal services) is amended as follows. Question put forthwith (Standing Order No. 163), and (2) After paragraph 41 (inquests) insert— negatived. “41A Investigation of deaths resulting from use of force Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Bill in mental health units (1) Civil legal services provided to an individual in relation to Consideration of Bill, as amended in the Public Bill an investigation under section (independent investigations of Committee deaths) of the Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018 (independent investigation of deaths) into the death of a member New Clause 1 of the individual’s family. -

Dying for Justice

Dying forJustice Edited by Harmit Athwal and Jenny Bourne Dying for Justice Edited by Harmit Athwal and Jenny Bourne Institute of Race Relations Notes and acknowledgements Chapters 1-5 have been written by Harmit Athwal, Jenny Bourne and Frances Webber. Other sections have been written by the authors indicated on each piece. Numerous individual families and their campaigns have, over the years, provided the inspiration and impetus for this report and the IRR’s onging work on the issue. We are also indebted to a host of volunteers, too many to name, who have helped us over the years. But we owe a special debt to Betsy Barkas, Ann Dryden, Trevor Hemmings and Mike Higgs. All pictures are copyright of IRR News unless otherwise specified. Cover: Vigil for Mikey Powell in September 2012. (© Ken Fero/Migrant Media) Pages 42-43: Top row, left-to-right Marcia Rigg and Stephanie Lightfoot-Bennett at a demonstration outside the CPS in August 2014. United Families and Friends annual remembrance procession in October 2013. Middle row, left-to-right Demonstration outside Yarl's Wood removal centre following death of Manuel Bravo in 2005. Demonstration outside Yarl's Wood removal centre following death of Manuel Bravo in 2005. Demonstration outside Harmondsworth removal centre in 2006. Adrienne Makenda Kambana, with Deborah Coles (INQUEST) and friends outside Isleworth Crown Court at the end of the inquest into the death of Jimmy Mubenga in 2013. Birthday vigil for Habib ‘Paps' Ullah in High Wycombe in December 2014. Bottom row, left-to-right Stafford Scott at a demonstration outside the offices of the IPCC in 2012. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 639 24 April 2018 No. 126 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 24 April 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 713 24 APRIL 2018 714 Richard Burgon (Leeds East) (Lab): Thousands of House of Commons key court staff were axed, but the Government are now spending tens of millions of pounds more on contracting agency staff. More than 100 courts were sold off, each Tuesday 24 April 2018 raising not much more than the average house price. Now the Secretary of State has appointed someone The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock with a slash-and-burn record as the new chair of the HMCTS board, telling the press that Tim Parker’s PRAYERS “expertise will be vital as we deliver our reform and modernisation of the courts”. [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] To allay concerns that Mr Parker has been appointed for his toughness on cuts, can the Minister outline the specific expertise that Mr Parker has in working in our Oral Answers to Questions court system? Lucy Frazer: The hon. Gentleman makes a number of points that I would like to refute, but I will mainly JUSTICE concentrate on two. It is important that where successful people in business put themselves forward for public The Secretary of State was asked— service, we should welcome them and not put off Court Closures experienced people from taking up important posts. -

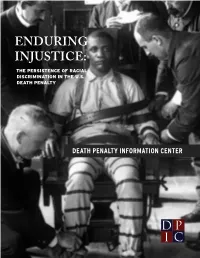

Enduring Injustice: the Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the U.S

ENDURING INJUSTICE: THE PERSISTENCE OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE U.S. DEATH PENALTY DEATH PENALTY INFORMATION CENTER MAY 28, 2010, 8:45 P.M. Racism, shmacism. Get a rope and let’s go hang us one. Anonymous comment on news story about Andrew Ramseur’s capital case, www.statesville.com (Statesville Record & Landmark) ENDURINGTHE PERSISTENCE OF RACIAL INJUSTICE DISCRIMINATION IN THE U.S. DEATH PENALTY A Report By The Death Penalty Information Center Principal Author: Ngozi Ndulue Edited by Robert Dunham September 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 27 Race Still Matters: The Continuing Role of Race in the Modern Death Penalty 2 Race and the Death Penalty Through U.S. History 28 Modern Capital Punishment Trends: Declining Use but Continuing Disparities 3 Capital Punishment in the Colonial and 33 Race Matters at Every Stage of Antebellum Period a Capital Case 5 Death in the Shadow of the Lynch Mob 37 Arrest and Homicide Clearance Rates 7 Mass Violence and Community Terror 37 Prosecutorial Charging 10 Anti-Lynching Campaigns 39 Jury Selection 12 Capital Punishment as an Acceptable 39 Death Qualification Alternative to Lynchings 40 Peremptory Strikes 14 Similarities Between Public Spectacle 43 The Impact of Non-Diverse Juries Lynchings and Public Executions 43 Defense Counsel 16 Race and Executions Between the 46 Sentencing and the Determination Lynching Era and the Civil Rights Era of “Deathworthiness” 18 Beginning the Modern Era: Race 48 Wrongful Convictions and Challenges at the U.S. Supreme Court Exonerations 22 Beyond Black and White: Race, 51 The Aftermath of McCleskey: Are Race Ethnicity, Sovereignty and the History Challenges Doomed in the Modern Era? of the Death Penalty 53 The Death Penalty in the Era of the New Jim Crow and Black Lives Matter 23 The Death Penalty, Native American Sovereignty, and U.S. -

George Floyd

Volume 97 Number 43 | JUNE 10-16, 2020 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents “Floyd was someone who also had a beautiful soul. If he was told he would have to sacrifice his life to bring the world together, I know he would've did it." RODNEY FLOYD Younger brother of George Floyd George Floyd is laid to rest amid criminal justice reform PENNY DICKERSON, Managing Editor lean frame and a mural hung on a stage [email protected] behind the casket that depicted the Chris- tian street evangelist wearing a black cap Black man’s body is laid to rest in a casket. Four ex-police officers are in custody. Pro- against a backdrop of white angel wings. testors world-wide have been subjected to curfews and a voluminous call for ‘change’ The symbolic homegoing was described persists. The alliterative aftermath of George Floyd’s death on May 25 has altered the as being dignified and attended by states- A men, celebrities and civil rights leaders. humanitarian fabric that monitors everyone’s pulse. Floyd’s last breath also tempered racial conflicts that have heightened since Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. first dreamed. SEE FLOYD 4A Floyd’s funeral was held Tuesday in a her 6’4” ‘gentle giant’ into the world and private service in Houston, where he was served as his final outcry for raised. His final burial was in Houston help before he took his last Memorial Gardens cemetery in suburban breath. Pearland next to his mother — Larcenia His coffin was gold, a brown Floyd — who brought suit was fitted to clothe his Today BUSINESS................