XU Magazine: Features Main

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloister Chronicle 317

liOISTER+ CnROIDCliFL ST. JOSEPH'S PROVINCE The Fathers and Brothers of St. Joseph's Province extend Sympathy their prayers and sympathy to the Rev. V. F. Kienberger, O.P., and to the Rev. F. ]. Barth, O.P., on the death of their mothers; to the Rev. C. M. Delevingne, O.P., on the death of his brother. St. Vincent Ferrer's Church in New York was honored on Cloister Oct. 10, by a visit of His Eminence, Eugenio Cardinal Visitors Pacelli, Papal Secretary of State. Accompanied by His Eminence, Patrick Cardinal Hayes, Archbishop of New York, the Cardinal Secretary made a thorough tour of the beautiful church. His Excell ency, the Most Rev. John T. McNicholas, O.P., Archbishop of Cincinnati, returned to St. Joseph's Priory, Somerset, Ohio, on the oc casion of the thirty-fifth anniversary of his elevation to the Holy Priest hood. The Archbishop celebrated Mass in St. Joseph's Church on the morning of Oct. 10. Before returning home, he spent some two hours in conversation with the Brother Students. Sept. 20-21, Immaculate Conception Convent in Washington was host to the Most Rev. John Francis Noll, D.D., B:shop of Fort W ayne, Ind., whose visit was occasioned by the investiture of the late Rt. Rev. Msgr. John J. Burke, C.S.P. Tuesday, Oct. 20, the Most Rev. Stephen J. Donahue, D.D., Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of New York, administered the Sacrament of Confirmation to a large class of children and adults at St. Vincent Ferrt!r's, in New York. -

Glossary, Bibliography, Index of Printed Edition

GLOSSARY Bishop A member of the hierarchy of the Church, given jurisdiction over a diocese; or an archbishop over an archdiocese Bull (From bulla, a seal) A solemn pronouncement by the Pope, such as the 1537 Bull of Pope Paul III, Sublimis Deus,proclaiming the human rights of the Indians (See Ch. 1, n. 16) Chapter An assembly of members, or delegates of a community, province, congregation, or the entire Order of Preachers. A chapter is called for decision-making or election, at intervals determined by the Constitutions. Coadjutor One appointed to assist a bishop in his diocese, with the right to succeed him as its head. Bishop Congregation A title given by the Church to an approved body of religious women or men. Convent The local house of a community of Dominican friars or sisters. Council The central governing unit of a Dominican priory, province, congregation, monastery, laity and the entire Order. Diocese A division of the Church embracing the members entrusted to a bishop; in the case of an archdiocese, an archbishop. Divine Office The Liturgy of the Hours. The official prayer of the Church composed of psalms, hymns and readings from Scripture or related sources. Episcopal Related to a bishop and his jurisdiction in the Church; as in "Episcopal See." Exeat Authorization given to a priest by his bishop to serve in another diocese. Faculties Authorization given a priest by the bishop for priestly ministry in his diocese. Friar A priest or cooperator brother of the Order of Preachers. Lay Brother A term used in the past for "cooperator brother." Lay Dominican A professed member of the Dominican Laity, once called "Third Order." Mandamus The official assignment of a friar or a sister to a Communit and ministry related to the mission of the Order. -

De La Nueva Alianza Una Publicación De La Curia General C.PP.S

MISIONEROS DE LA PRECIOSA SANGRE El No. 34, Abril 2013 Cáde lla Nizueva Alianza Reflexionando sobre nuestras “Historias” por P. Francesco Bartoloni, C.PP.S. on la presente edición de El Cáliz Ccomenzamos a reflexionar sobre la celebración del bicentenario de la fundación de la Congregación que ya está a las puertas . La comisión inter - nacional ha programado para la cele - bración del bicentenario de la Congregación un trienio de reflexión y oración . El tema del primer año, que examina la historia ya vivida pero aún no concluida, gira en torno a la siguiente formulación : no sólo tene - mos una historia para recordar y com - partir , sino también una gran historia por completar . La razón central de la celebración del bicentenario es para dar gracias por el carisma que, a través de nosotros y de nuestro compromiso, Dios ha dado a la Iglesia y al mundo . Otro motivo de Ver página 36 Estatua de San Gaspar del Búfalo (en San Felice, Giano) NOTA LOS COMIENZOS DE LA C.PP.S. DEL EDITOR Selecciones hechas por P. Mark Miller, C.PP.S. tomadas de “Historical Sketches of C.PP.S.” Los artículos publicados en por P. Andrew Pollack, C.PP.S. este edición de El Cáliz por e ha dicho que antes de toda rea - En sus primeros años Gaspar contó los general son extractos lidad tiene que haber un sueño . Es con el apoyo de un pequeño grupo de seleccionados y editados S lo que sucedió en el caso de los sacerdotes que también creían en el de artículos más largos de Misioneros de la Preciosa Sangre, una sueño de ser misioneros . -

2010:Frntpgs 2004.Qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai

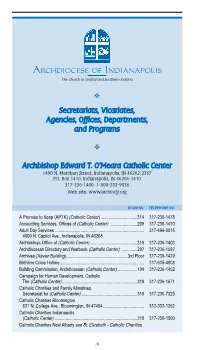

frntpgs_2010:frntpgs_2004.qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai Archdiocese of Indianapolis The Church in Central and Southern Indiana ✜ Secretariats, Vicariates, Agencies, Offices, Departments, and Programs ✜ Archbishop Edward T. O’Meara Catholic Center 1400 N. Meridian Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-2367 P.O. Box 1410, Indianapolis, IN 46206-1410 317-236-1400 1-800-382-9836 Web site: www.archindy.org ROOM NO. TELEPHONE NO. A Promise to Keep (APTK) (Catholic Center) ................................314 317-236-1478 Accounting Services, Offices of (Catholic Center) ........................209 317-236-1410 Adult Day Services .............................................................................. 317-466-0015 4609 N. Capitol Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46208 Archbishop, Office of (Catholic Center)..........................................319 317-236-1403 Archdiocesan Directory and Yearbook (Catholic Center) ..............207 317-236-1587 Archives (Xavier Building)......................................................3rd Floor 317-236-1429 Birthline Crisis Hotline.......................................................................... 317-635-4808 Building Commission, Archdiocesan (Catholic Center)..................104 317-236-1452 Campaign for Human Development, Catholic The (Catholic Center) ..................................................................319 317-236-1571 Catholic Charities and Family Ministries, Secretariat for (Catholic Center)..................................................319 317-236-7325 Catholic Charities Bloomington -

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: 2

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: 2. Reverend Joseph A. Stephan, 1884-1901 Kevin Abing, 1994 Brouillet's successor, Father Joseph A. Stephan, was known as the "fighting" priest. Perhaps the sobriquet derived from Stephan's Civil War experience. More likely, however, the name reflected Stephan's personality. Whereas Brouillet favored negotiation and compromise, Stephan actively sought confrontation. As director, Stephan infused the BCIM with a "new and aggressive energy."1 Stephan's combativeness often served him and the Bureau well, but all too often, his stubbornness and volatile temper hindered the cause he served so faithfully. As Charles Lusk wrote, Stephan's "zeal for the Indians was unbounded and his courage great." But, Lusk mused, sometimes Stephan's "zeal might have been tempered with greater discretion."2 Joseph A. Stephan was born on November 22, 1822, at Gissigheim, in the duchy of Baden. His father was of Greek descent, and his mother was probably Irish.3 As a youth, Stephan attended the village school in Gissigheim and later served an apprenticeship in the carpentry trade at Koenigsheim. Apparently, the life of a carpenter did not suit Stephan for he eventually joined the military, eventually becoming an officer under Prince Chlodwig K. Victor von Hohenlode. To further his military career, Stephan studied civil engineering at Karlsruhe Polytechnic Institute and philology at the University of Freiburg.4 While studying at Freiburg, disaster struck. From some unknown cause, Stephan was struck blind for two years. Similar to Saint Paul, Stephan turned to God during this trial. He reportedly pledged to become a priest if his eyesight returned. -

Archbishop's Letter

Happy 200th Birthday Archbishop Lamy! Archbishop Michael J. Sheehan, People of God, October 2014 The founding bishop of Santa Fe was Jean-Baptiste Lamy. He was born on October 11, 1814 in Lempdes, Puy-de-Dôme, in the Auvergne region of France. The Archdiocese of Clermont in France is celebrating his 200th birthday with several events this month. I have appointed Msgr. Bennett J. Voorhies, pastor of Our Lady of the Annunciation in Albuquerque (he is also dean of Albuquerque Deanery B) as my representative as he is fluent in French. Archbishop Lamy completed his classical studies in the Minor Seminary at Clermont and theological coursework in the Major Seminary at Montferrand, where he was trained by the Sulpician fathers. He was ordained a priest at the age of 24 on December 22, 1838; he asked for and obtained permission to serve as a missionary for Bishop John Baptist Purcell, of Cincinnati, Ohio. As a missionary, he served at several missions in Ohio and Kentucky. Pope Pius IX appointed him as bishop of the recently created Apostolic Vicariate of New Mexico on July 23, 1850; he was only 36 years old. He was consecrated as a bishop on November 24, 1850 by Archbishop Martin Spalding of Louisville; Bishops Jacques-Maurice De Saint Palais of Vincennes and Louis Amadeus Rappe of Cleveland served as co-consecrators. After a long and dangerous journey by horse and wagon train, he finally reached Santa Fe. He entered Santa Fe on August 9, 1851 and was welcomed by Governor James S. Calhoun and many citizens. -

Bring Perspectives on Hope, Homelessness and Forgiveness

Pastoral Care and Counseling Newsletter Pastoral Care and Neumann College Counseling Newsletter October, 2008 Neumann College, Visitors to Campus One Neumann Drive, Aston, PA 19014-1298 February, 2008 Bring Perspectives on Hope, ____________________________________________ The Pastoral Care and Counseling Newsletter is Homelessness and Forgiveness a department publication issued several times dur- ing the academic year. Since the opening of the Written by and for the school term in August, five highly re- members of the Pastoral garded persons have visited the Neu- Care and Counseling De- mann campus in response to invita- partment, it contains ar- tions from the Pastoral Care and ticles, reviews, inter- Counseling program. Two of these views and forms of re- five have been singular speakers at flective material of inter- events in the PCC Lecture series. est to these members sub- The other three served as a panel to mitted in advance to the provide input for the Fall Evening of editor of the publication. The streets of North Philadelphia to Enrichment. Editor: Suzanne Mayer, which Suzanne Neisser’s, rsm, minis- On Wednesday evening, Sep- try took her [upper] contrasts greatly ihm, Ph.D. tember 10 as is traditional, the three with Cranaleith, the Center to which Photography: Len Di- evenings of classes collapsed into one she took her retreatants [lower]. Paul, Ed.D. to allow all students in whatever Contributors: Eileen courses or programs to attend the Fall program, all of whom work with the Flanagan , Ph.D. Jim Evening of Enrichment. The focus of severely mentally ill and/or homeless Houck, Ph.D. this year’s gathering was an arti- spoke of their involvement in this cle that appeared in a recent ministry. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

Us Catholic Schools and the Religious Who Served in Them Contributions In

364 ARTICLES U.S. CATHOLIC SCHOOLS AND THE RELIGIOUS WHO SERVED IN THEM CONTRIBUTIONS IN THE 18TH AND 19TH CENTURIES RICHARD M. JACOBS. O.S.A. Villanova University This article, the first in a series of three articles surveying the contributions of the religious to U.S. Catholic schooling, focuses upon their contributions during the 18th and 19th centuries. ith the colonists establishing a life for themselves on North American Wsoil, the Spanish Franciscans commissioned friars to minister in the New World. In 1606, the first band of friars opened the first Catholic school in the New World, located in St. Augustine, Florida, dedicating it "to teach children Christian doctrine, reading and writing" (Kealey, 1989). Not long afterward, other religious communities followed in these pioneering Franciscans' footsteps. Over the next 294 years—an era during which the colonies revolted against the crown to become the United States of America, citizens fought a civil war to abolish slavery, and millions of Catholic immigrants journeyed from the Old World to the New World—the successors of these pioneering religious contributed mightily to establishing Catholic schooling in the United States. The religious not only staffed schools, they educated the poor and marginalized, solidified the schools' institutional purpose, and provided students with effective values-based instruction. Furthermore, they estab- lished teacher preparation programs to better assure quality teaching for the young. Catholic Education: A Joumal of Inquiry and Practice. Vol. 1, No. 4, June 1998, 364-383 <'Jl998 Catholic Education: A Journal of^ Inquiry and Practice Richard M. Jacobs, O.S.A./CATHOLIC SCHOOLS AND RELIGIOUS WHO SERVED 365 STAFFING CATHOLIC SCHOOLS As the number of Catholic schools gradually increased, providing teachers became a more pressing need. -

Cushwa News Vol 31 No 2

AMERICAN CATHOLIC STUDIES NEWSLETTER CUSHWA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF AMERICAN CATHOLICISM The Founding of the Notre Dame Archives f it is true that every success- Senior Departments (grade school, high across the country wrote with requests ful institution is simply the school, and early college), interrupted his for blessed rosaries, Lourdes water, papal shadow of a great man or education briefly to try the religious life, blessings, and even with complaints woman, then the Notre Dame returned to his studies, and was invited when their copies of Ave Maria Magazine Archives are surely the shad- to join the Notre Dame faculty in 1872. did not arrive.Young Father Matthew ow of Professor James Edwards remained at Notre Dame Walsh, C.S.C., future Notre Dame presi- Farnham (“Jimmie”) Edwards. for the rest of his life, dying there in dent, wrote from Washington for advice Edwards was born in Toledo, Ohio, 1911 and being laid to rest in the Holy about selecting a thesis topic. Hearing Iin 1850, of parents who had emigrated Cross Community Cemetery along the that the drinking water at Notre Dame from Ireland only two years before. His road to Saint Mary’s. He began by teach- had medicinal qualities, one person father was successively co-owner of ing Latin and rhetoric in the Junior wrote to ask if the water was from a Edwards and Steelman Billiard rooms, (high school) Department, received a mineral spring or if the iron was put into proprietor of the Adelphi Theater, bachelor of laws degree in 1875, and was it by the sisters. -

Chronology: Athenaeum, St. Xavier College, Xavier University J

Xavier University Exhibit Journals, Publications, Conferences, and Publications on Xavier University History Proceedings 6-1-1975 Chronology: Athenaeum, St. Xavier College, Xavier University J. Peter Buschmann Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/ebooks Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Buschmann, J. Peter, "Chronology: Athenaeum, St. Xavier College, Xavier University" (1975). Publications on Xavier University History. 18. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/ebooks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Publications, Conferences, and Proceedings at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications on Xavier University History by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chronology ****** XAVIER UNIVERSITY ****** Rev. J. Peter Buschmann, S.J. CHRONOLOGY ATHENAEUM - ST. XAVIER COLLEGE - XAVIER UNIVERSITY An arrangement of historical events and related incidents of interest • in the order of occurrence . Rev. J. Peter Buschmann, S.Jo Xavier University Cincinnati, Ohio 'i. June 1, 1975 • • 1 Chronology Athenaeum - St. Xavier College - Xavier University INTRODUCTION .. In 1749 the Jesuit, Father Joseph-Pierre de Bonnecamps, accompanied the expedition led by Celeron de Bienville down the Ohio, and made the first survey and map of Ohio. The party encamped August 28 to 31, near the mouth of the Little Miami River. It is very probable that Father Bonnecamps offered Mass at this site. The Northwest Territory was organized in 1787. It included all of the land west of the Allegheny Mountains, north of the Ohio River, and east of the.Mississippi River. Ohio attained Statehood in 1803 as the seventeenth State of the Union. -

The Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati: 1829–1852

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 17 Issue 3 Article 4 Fall 1996 The Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati: 1829–1852 Judith Metz S.C. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Metz, Judith S.C. (1996) "The Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati: 1829–1852," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 17 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol17/iss3/4 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 201 The Sisters of Charity in Cincinnati 1829-1852 BY JUDITH MFTZ, S.C. Standing at the window of the Cathedral residence shortly before his death, and noticing the sisters passing by, Arch- bishop John Baptist Purcell commented to a friend, "Ah, there go the dear Sisters of Charity, the first who gave me help in all my undertakings, the zealous pioneer religious of this city, and the first female religious of Ohio,—who were never found wanting, and who always bore the brunt of the battle.' When four Sisters of Charity arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio, in Octo- ber 1829 to open an orphanage and school, they were among the trailblazers in establishing the Roman Catholic Church on a sound footing in a diocese which encompassed almost the entire Northwest Territory. These women were members of a Catholic religious com- munity founded in 1809 by Elizabeth Bayley Seton with its motherhouse in Emmitsburg, Maryland.