Us Catholic Schools and the Religious Who Served in Them Contributions In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Influences Designing Albanian Schools Architecture

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 Foreign Influences Designing Albanian Schools Architecture Ledita Mezini Lecturer at Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning, Polytechnic University of Tirana, Albania Abstract: Throughout history, Albania was a battlefield of several wars, assaulted from other countries and always struggling to survive and preserveits traditions, language and culture. Invasions happened through guns and battles but also through the extent of foreign languages and culture ineducation. The education sector and structures that hosted it, passed through stages of transformations, developments and regressions dependent on the course of history and the forces of foreign countries shaping it. The main objective of this research is to highlight the Albanian school buildings through two parallel points of view: an outlookthrough the course of history and analyzed as structures. This article tries to explore the changes that occurred in educational buildings in Albania.Itfocuses on the influences, problems and issues that have emerged, during the several invasions and how these influences have affected the architecture of Albanian’s schools. This analysis is followed by a discussion of the architecture’s development and the typology, standards, structures and shapes of this category of buildings focusing mostly on the last century, trying to fill the gap of history and knowledge for this important group of edifices. Keywords: Albania, school architecture, transformation of buildings, history, educational structures. 1. Introduction and the edifices that support it, suffered the course of history, transformed and shaped by these political and social “The physical and typological changes in school‟s events. -

Faith Formation Handbook Blessed Sacrament Parish Community 3109 Swede Ave, Midland MI 48642-3842 (989) 835-6777, Fax (989) 835-2451

Faith Formation Handbook Blessed Sacrament Parish Community 3109 Swede Ave, Midland MI 48642-3842 (989) 835-6777, Fax (989) 835-2451 September 7, 2019 Dear People of God, Soon we will be starting this year’s faith formation programs. The opportunity to learn about our relationship with God is an amazing gift. I cannot think of another thing that not only impacts our lives now but will also echo for all eternity. I am personally excited to be walking this journey with you and your families. As you may already know…our focus is on truly being TEAM CATHOLIC. Being the part of any team requires cooperation and a common goal. Our goal is to do our part to help bring about the kingdom of God. We do just that whenever we take the gifts that God gives us and share them freely with one another. Allow me a quick sports analogy. In the late 1980’s Steve Yzerman was a perennial top scorer in the National Hockey League. In spite of that, the Red Wings couldn’t win in the playoffs. That was until their coach asked Yzerman to change his playing style. This change, while costing him individual statistics, would turn him into a defensive superstar and transform the Red Wings into Stanley Cup Champs. As a member of TEAM CATHOLIC it isn’t about individual accolades but is about the team. We want all people to know that they are valued and that they are part of this diverse and sometimes quirky family we call the Church. -

Lonergan on the Catholic University Richard M Liddy, Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University From the SelectedWorks of Richard M Liddy October, 1989 Lonergan on the Catholic University Richard M Liddy, Seton Hall University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/richard_liddy/13/ Lonergan on the Catholic University Msgr. Richard M. Liddy Seton Hall University South Orange, NJ A version of this appeared as "Lonergan on the Catholic University," Method: Journal of Lonergan Studies, vol. 7, no. 2 (October 1989), 116 - 131. LONERGAN ON THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY Msgr. Richard M. Liddy In 1951 Bernard Lonergan wrote an article entitled "The Role of a Catholic University in the Modern World." Originally published in French, it can be found in Lonergan's Collection.1 Published at the same time he was working on his magnum opus, Insight, it reflects the basic thrust of that major work. Some years later, in 1959, in a series of lectures in Cincinnati on the philosophy of education Lonergan touched again upon the subject of the Catholic university.2 Here he adverted to the fact that of its very nature the whole immense Catholic school system is rooted in a "supernaturalist vision" that is in conflict with the dominant philosophies of education of modern times. The fact is that we have a Catholic educational system, with primary schools, high schools, colleges and universities. That is the concrete fact and it exists because it is Catholic.3 What Lonergan finds lacking is a philosophical vision capable of defending the existence of the Catholic school system. Educational theorists tend to be divided into "modernists" whose appeal is to human experience and scientific verification and "traditionalists" who appeal to immutable truths transcending scientific verification. -

The Albanian

The Albanian Finchley Catholic High School, Woodside Lane, Finchley N12 ODA October 2018 Volume 26, Issue 1 Message from the Head Our new academic year has begun very positively. Our students have already undertaken several activities Thank you to our parental community for working to support the common good, which is a huge focus for collaboratively with us for our students’ benefit. We us here at our Catholic School. really appreciate your support, cooperation and open communication as it enables us to meet our students’ Thank you for supporting our boys and girls to needs more effectively. Staff try to ensure that parents participate and be involved in events which continue to are in receipt of the information they require and will find make a very real difference for the Community. You will interesting and useful. If there are any areas in which see in this edition a few pictures from our Cafod fast you need further details or explanation, please let us day, MacMillan Coffee morning and our 6th form Mary’s know so we can further strengthen our working Meals fund raiser. partnership . In addition to these events, Year 10 students have Please remember to check our website regularly for raised funds for a mental health charity and a number of updates and follow us on Twitter (@fchslondon) for other charitable events are already planned for next half news and updates. term. We had our Year 7 Welcome Event on October 4th, One of the most enjoyable aspects of my role is the time which was a wonderful occasion. -

Teen Night 2021-2022 Family Handbook

St. Eugene & St. Monica Teen Night 2021-2022 Family Handbook “Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks, receives; and the one who seeks, finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened.” - Matthew 7: 7-8 - STME Youth Ministry Our Confirmation Team Thaddeus Loduha, Associate Director for Youth Ministry 414.964.8780 Ext. 124 [email protected] Meaghan Turner, Director of Adult & Youth Ministry 414.964.8780 Ext. 156 [email protected] Juliette Anderson, CYM Coordinator 414.332.1576 Ext. 136 [email protected] Father Jordan Berghouse, STME Associate Pastor 414.332.1576 Ext. 106 [email protected] Youth Ministry Hub Mailing Address & Drop off Site: STME Ministry Center 5681 N Santa Monica Blvd, WFB 53217 www.stme.church Follow Us On Instagram! STMEYouthMinistry MISSION: To provide every high school student in our parishes the opportunity to experience a personal relationship with our Lord, and in that relationship with Him, to discover the richness of our Catholic faith and learn to live as His disciples. Youth Ministry Teen Nights Who are Youth Ministry (YM) Teen Nights For? Teen Nights are for all high school students, and specifically the 9th and 10th grade formation ministry leading up to Confirmation. This includes teens who attend both public and Catholic High School. TEEN NIGHT SESSIONS We plan to run Teen Night ministry in the format of 22+ sessions from September—April during Wednesday evenings at St. Monica @ 7:00 - 8:30 pm Wed, Sept -

The Challenge and Promise of Catholic Higher Education: the Lay President and Catholic Identity

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The hC allenge and Promise of Catholic Higher Education: The Lay President and Catholic Identity Kathy Ann Herrick Marquette University Recommended Citation Herrick, Kathy Ann, "The hC allenge and Promise of Catholic Higher Education: The Lay President and Catholic Identity" (2011). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 155. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/155 THE CHALLENGE AND PROMISE OF CATHOLIC HIGHER EDUCATION: THE LAY PRESIDENT AND CATHOLIC IDENTITY by Kathy A. Herrick, B.S., M.S.E. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin December 2011 ABSTRACT THE CHALLENGE AND PROMISE OF CATHOLIC HIGHER EDUCATION: THE LAY PRESIDENT AND CATHOLIC IDENTITY Kathy A. Herrick, B.S., M.S.E. Marquette University, 2011 Twenty years after Ex Corde Ecclesiae, the papal proclamation that defined the relationship between the Catholic Church and Catholic institutions of higher education, these institutions continue to seek ways to strengthen their Catholic identities. As they do so they are faced with a declining number of religiously vowed men and women available to lead them. An institution‘s history is often linked to the mission of its founding congregation. As members of the congregation become less actively involved, the connection of the institution‘s mission to the founding congregation and their particular charism is likely to be less visibly evident. Additionally, the role of the American university president today is viewed by many to be an almost impossible job. -

Cloister Chronicle 317

liOISTER+ CnROIDCliFL ST. JOSEPH'S PROVINCE The Fathers and Brothers of St. Joseph's Province extend Sympathy their prayers and sympathy to the Rev. V. F. Kienberger, O.P., and to the Rev. F. ]. Barth, O.P., on the death of their mothers; to the Rev. C. M. Delevingne, O.P., on the death of his brother. St. Vincent Ferrer's Church in New York was honored on Cloister Oct. 10, by a visit of His Eminence, Eugenio Cardinal Visitors Pacelli, Papal Secretary of State. Accompanied by His Eminence, Patrick Cardinal Hayes, Archbishop of New York, the Cardinal Secretary made a thorough tour of the beautiful church. His Excell ency, the Most Rev. John T. McNicholas, O.P., Archbishop of Cincinnati, returned to St. Joseph's Priory, Somerset, Ohio, on the oc casion of the thirty-fifth anniversary of his elevation to the Holy Priest hood. The Archbishop celebrated Mass in St. Joseph's Church on the morning of Oct. 10. Before returning home, he spent some two hours in conversation with the Brother Students. Sept. 20-21, Immaculate Conception Convent in Washington was host to the Most Rev. John Francis Noll, D.D., B:shop of Fort W ayne, Ind., whose visit was occasioned by the investiture of the late Rt. Rev. Msgr. John J. Burke, C.S.P. Tuesday, Oct. 20, the Most Rev. Stephen J. Donahue, D.D., Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of New York, administered the Sacrament of Confirmation to a large class of children and adults at St. Vincent Ferrt!r's, in New York. -

Glossary, Bibliography, Index of Printed Edition

GLOSSARY Bishop A member of the hierarchy of the Church, given jurisdiction over a diocese; or an archbishop over an archdiocese Bull (From bulla, a seal) A solemn pronouncement by the Pope, such as the 1537 Bull of Pope Paul III, Sublimis Deus,proclaiming the human rights of the Indians (See Ch. 1, n. 16) Chapter An assembly of members, or delegates of a community, province, congregation, or the entire Order of Preachers. A chapter is called for decision-making or election, at intervals determined by the Constitutions. Coadjutor One appointed to assist a bishop in his diocese, with the right to succeed him as its head. Bishop Congregation A title given by the Church to an approved body of religious women or men. Convent The local house of a community of Dominican friars or sisters. Council The central governing unit of a Dominican priory, province, congregation, monastery, laity and the entire Order. Diocese A division of the Church embracing the members entrusted to a bishop; in the case of an archdiocese, an archbishop. Divine Office The Liturgy of the Hours. The official prayer of the Church composed of psalms, hymns and readings from Scripture or related sources. Episcopal Related to a bishop and his jurisdiction in the Church; as in "Episcopal See." Exeat Authorization given to a priest by his bishop to serve in another diocese. Faculties Authorization given a priest by the bishop for priestly ministry in his diocese. Friar A priest or cooperator brother of the Order of Preachers. Lay Brother A term used in the past for "cooperator brother." Lay Dominican A professed member of the Dominican Laity, once called "Third Order." Mandamus The official assignment of a friar or a sister to a Communit and ministry related to the mission of the Order. -

De La Nueva Alianza Una Publicación De La Curia General C.PP.S

MISIONEROS DE LA PRECIOSA SANGRE El No. 34, Abril 2013 Cáde lla Nizueva Alianza Reflexionando sobre nuestras “Historias” por P. Francesco Bartoloni, C.PP.S. on la presente edición de El Cáliz Ccomenzamos a reflexionar sobre la celebración del bicentenario de la fundación de la Congregación que ya está a las puertas . La comisión inter - nacional ha programado para la cele - bración del bicentenario de la Congregación un trienio de reflexión y oración . El tema del primer año, que examina la historia ya vivida pero aún no concluida, gira en torno a la siguiente formulación : no sólo tene - mos una historia para recordar y com - partir , sino también una gran historia por completar . La razón central de la celebración del bicentenario es para dar gracias por el carisma que, a través de nosotros y de nuestro compromiso, Dios ha dado a la Iglesia y al mundo . Otro motivo de Ver página 36 Estatua de San Gaspar del Búfalo (en San Felice, Giano) NOTA LOS COMIENZOS DE LA C.PP.S. DEL EDITOR Selecciones hechas por P. Mark Miller, C.PP.S. tomadas de “Historical Sketches of C.PP.S.” Los artículos publicados en por P. Andrew Pollack, C.PP.S. este edición de El Cáliz por e ha dicho que antes de toda rea - En sus primeros años Gaspar contó los general son extractos lidad tiene que haber un sueño . Es con el apoyo de un pequeño grupo de seleccionados y editados S lo que sucedió en el caso de los sacerdotes que también creían en el de artículos más largos de Misioneros de la Preciosa Sangre, una sueño de ser misioneros . -

2010:Frntpgs 2004.Qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai

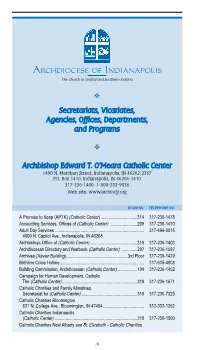

frntpgs_2010:frntpgs_2004.qxd 6/21/2010 4:57 PM Page Ai Archdiocese of Indianapolis The Church in Central and Southern Indiana ✜ Secretariats, Vicariates, Agencies, Offices, Departments, and Programs ✜ Archbishop Edward T. O’Meara Catholic Center 1400 N. Meridian Street, Indianapolis, IN 46202-2367 P.O. Box 1410, Indianapolis, IN 46206-1410 317-236-1400 1-800-382-9836 Web site: www.archindy.org ROOM NO. TELEPHONE NO. A Promise to Keep (APTK) (Catholic Center) ................................314 317-236-1478 Accounting Services, Offices of (Catholic Center) ........................209 317-236-1410 Adult Day Services .............................................................................. 317-466-0015 4609 N. Capitol Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46208 Archbishop, Office of (Catholic Center)..........................................319 317-236-1403 Archdiocesan Directory and Yearbook (Catholic Center) ..............207 317-236-1587 Archives (Xavier Building)......................................................3rd Floor 317-236-1429 Birthline Crisis Hotline.......................................................................... 317-635-4808 Building Commission, Archdiocesan (Catholic Center)..................104 317-236-1452 Campaign for Human Development, Catholic The (Catholic Center) ..................................................................319 317-236-1571 Catholic Charities and Family Ministries, Secretariat for (Catholic Center)..................................................319 317-236-7325 Catholic Charities Bloomington -

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: 2

Directors of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions: 2. Reverend Joseph A. Stephan, 1884-1901 Kevin Abing, 1994 Brouillet's successor, Father Joseph A. Stephan, was known as the "fighting" priest. Perhaps the sobriquet derived from Stephan's Civil War experience. More likely, however, the name reflected Stephan's personality. Whereas Brouillet favored negotiation and compromise, Stephan actively sought confrontation. As director, Stephan infused the BCIM with a "new and aggressive energy."1 Stephan's combativeness often served him and the Bureau well, but all too often, his stubbornness and volatile temper hindered the cause he served so faithfully. As Charles Lusk wrote, Stephan's "zeal for the Indians was unbounded and his courage great." But, Lusk mused, sometimes Stephan's "zeal might have been tempered with greater discretion."2 Joseph A. Stephan was born on November 22, 1822, at Gissigheim, in the duchy of Baden. His father was of Greek descent, and his mother was probably Irish.3 As a youth, Stephan attended the village school in Gissigheim and later served an apprenticeship in the carpentry trade at Koenigsheim. Apparently, the life of a carpenter did not suit Stephan for he eventually joined the military, eventually becoming an officer under Prince Chlodwig K. Victor von Hohenlode. To further his military career, Stephan studied civil engineering at Karlsruhe Polytechnic Institute and philology at the University of Freiburg.4 While studying at Freiburg, disaster struck. From some unknown cause, Stephan was struck blind for two years. Similar to Saint Paul, Stephan turned to God during this trial. He reportedly pledged to become a priest if his eyesight returned. -

Archbishop's Letter

Happy 200th Birthday Archbishop Lamy! Archbishop Michael J. Sheehan, People of God, October 2014 The founding bishop of Santa Fe was Jean-Baptiste Lamy. He was born on October 11, 1814 in Lempdes, Puy-de-Dôme, in the Auvergne region of France. The Archdiocese of Clermont in France is celebrating his 200th birthday with several events this month. I have appointed Msgr. Bennett J. Voorhies, pastor of Our Lady of the Annunciation in Albuquerque (he is also dean of Albuquerque Deanery B) as my representative as he is fluent in French. Archbishop Lamy completed his classical studies in the Minor Seminary at Clermont and theological coursework in the Major Seminary at Montferrand, where he was trained by the Sulpician fathers. He was ordained a priest at the age of 24 on December 22, 1838; he asked for and obtained permission to serve as a missionary for Bishop John Baptist Purcell, of Cincinnati, Ohio. As a missionary, he served at several missions in Ohio and Kentucky. Pope Pius IX appointed him as bishop of the recently created Apostolic Vicariate of New Mexico on July 23, 1850; he was only 36 years old. He was consecrated as a bishop on November 24, 1850 by Archbishop Martin Spalding of Louisville; Bishops Jacques-Maurice De Saint Palais of Vincennes and Louis Amadeus Rappe of Cleveland served as co-consecrators. After a long and dangerous journey by horse and wagon train, he finally reached Santa Fe. He entered Santa Fe on August 9, 1851 and was welcomed by Governor James S. Calhoun and many citizens.