Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Training Schedule 2018.Xlsx

Training Schedule for Successful Hajj Applicants of Government Hajj Scheme - 2018 Sr. No. District Date Venue Time Training Arranged By JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 1 ABBOTTABAD 25-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 JALAL BABA AUDITORIUM, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 2 ABBOTTABAD 26-Mar-18 09 AM ABBOTTABAD 9247521, 9247575 PARADISE MARRIAGE HALL, MAIN Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 3 ATTOCK 28-Mar-18 09 AM RAWALPINDI ROAD, FATEH JANG 9247521, 9247575 TULIP MARQUE, CHINA CHOWK, Hajji Camp, Islamabad, Ph: (051) 4 ATTOCK 03-Apr-18 09 AM HAJI SHAH ROAD, ATTOCK 9247521, 9247575 Hajj Complex, Quetta, Ph: (081) 5 AWARAN 19-Apr-18 DISTRICT COUNCIL HALL, PANJGUR 09 AM 9213021, 9213326 QATAR MASJID, HYDERABAD Hajji Camp, Karachi, Ph: (021) 6 BADIN 28-Mar-18 10 AM ROAD, BADIN 99204761, 35688307 MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 7 BAHAWAL NAGAR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN 8 BAHAWAL NAGAR 03-Apr-18 OFFICERS CLUBE FORT ABBAS 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 INSAF MARRIAGE HALL OPPOSITE TABLEEGHI MARKAN 9 BAHAWAL NAGAR 04-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 HAROONABAD ROAD , BAHAWAL NAGHAR MILAN MARRIEGE CLUB, SUGER 10 BAHAWALPUR 02-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 MILL ROAD,CHISHTIAN QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 11 BAHAWALPUR 06-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. QUAID-E-AZAM MEDICAL 12 BAHAWALPUR 07-Apr-18 09 AM Hajji Camp, Multan, Ph: (061) 9330058 COLLEGE, BAHAWAL PUR. -

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East), G-511, Islamabad Ph: +92-51-9206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Web: www.nepra.org.pk, E-mail: [email protected] No. NEPRA/ADG(L)/LAN-2187/ / 6 Y 2 1- (3 September 17 2019 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, Phone No. 0301-8258533 Subject: Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 Licence Application No. LAN-2187 Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique, K — Electric Limited Ref KEL's letter No. KE/BPR/NEPRA/2019/624 dated 23.07.2019 (received on 29.07.2019) Enclosed please find herewith Generation Licence No. DGL/2187/2019 granted by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority to Mr. Zafar Aitmad Siddique for 05.20 kW photo voltaic solar based distributed generation facility located at R-3, Block-1, Gulistan-e-Johar, Karachi, under NEPRA (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015. 2. Please quote above mentioned Generation ence No. for future correspondence. Enclosure: Generation Licence (DGL/2187/2019) CA (Syed Safeer Hussain) Copy to: 1. Chief Executive Office, Alternative Energy Development Board, 2nd Floor, OPF Building, G-5/2, Islamabad. 2. Chief Executive Officer, K-Electric Limited, KE House, 39 B, Main Sunset Boulevard, DHA Phase-II, Karachi. 3. Director General, Environment Protection Department, Government of Sindh, Complex Plot No. ST-2/1, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi. National Electric Power f equlatory Authority NEP Is! mabad— kistan The Authority hereby grants Generation Licence to Mr. Zafar Aitvpad Siddique, for 5.20 KW photovoltaic solar based distributed generation facility, having consumer reference number LA912022, located at R-3, Block-I, Gulistan-e- Jouhar, Karachi under the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015 (the "A&RE Regulations") for a period of seven (07) years. -

269 Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant General 102–3

Index Abdul Aziz Angkat 17 Turkmenistan and 88 Abdul Qadir Baloch, Lieutenant US and 83, 99, 143–4, 195, General 102–3 252, 253, 256 Abeywardana, Lakshman Yapa 172 Uyghurs and 194, 196 Abu Ghraib 119 Zaranj–Delarum link highway 95 Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) 251, 260 Africa 5, 244 Abuza, Z. 43, 44 Ahmad Humam 24 Aceh 15–16, 17, 31–2 Aimols 123 armed resistance and 27 Akbar Khan Bugti, Nawab 103, 104 independence sentiment and 28 Akhtar Mengal, Sardar 103, 104 as Military Operation Zone Akkaripattu- Oluvil area 165 (DOM) 20, 21 Aksu disturbances 193 peace process and Thailand 54 Albania 194 secessionism 18–25 Algeria Aceh Legislative Council 24 colonial brutality and 245 Aceh Monitoring Mission (AMM) 24 radicalization in 264 Aceh Referendum Information Centre Ali Jan Orakzai, Lieutenant General 103 (SIRA) 22, 24 Al Jazeera 44 Acheh- Sumatra National Liberation All Manipur Social Reformation, women Front (ASNLF) 19 protesters of 126–7 Aceh Transition Committee (Komite All Party Committee on Development Peralihan Aceh) (KPA) 24 and Reconciliation ‘act of free choice’, 1969 Papuan (Sri Lanka) 174, 176 ‘plebiscite’ 27 All Party Representative Committee Adivasi Cobra Force 131 (APRC), Sri Lanka 170–1 adivasis (original inhabitants) 131, All- Assam Students’ Union (AASU) 132 132–3 All- Bodo Students’ Union–Bodo Afghanistan 1–2, 74, 199 Peoples’ Action Committee Balochistan and 83, 100 (ABSU–BPAC) 128–9, 130 Central Asian republics and 85 Bansbari conference 129 China and 183–4, 189, 198 Langhin Tinali conference 130 India and 143 al- Qaeda 99, 143, -

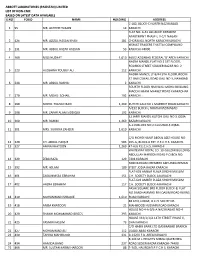

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

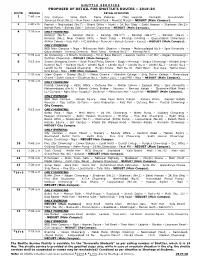

Shuttle Route

SHUTTLE SERVICES PROPOSED OF DETAIL FOR SHUTTLE’S ROUTES – 2019-20 ROUTE TIMINGS DETAIL OF ROUTES 1 7:40 a.m City Campus – Jama Cloth – Radio Pakistan – 7Day Hospital – Numaish – Gurumandir – Jamshed Road (No.3) – New Town – Askari Park – Mumtaz Manzil – NEDUET (Main Campus). 2 7:40 a.m Paposh – Nazimabad (No.7) – Board Office – Hydri – 2K Bus Stop – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman (No.2)– Namak Bank – Sohrab Goth – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 4 7:20 a.m ONLY MORNING: Korangi (No.5) – Korangi (No.4) – Korangi (No.31/2) – Korangi (No.21/2) – Korangi (No.2) – Korangi (No.1, Near Chakra Goth) – Nasir Jump – Korangi Crossing – Qayyumabad Chowrangi – Akhtar Colony – Kala Pull – FTC Building – Nursery – Baloch Colony – Karsaz – NEDUET (Main Campus). ONLY EVENING: NED Main Campus – Nipa – Millennium Mall– Stadium – Karsaz – Mehmoodabad No.6 – Iqra University – Qayyumabad – Korangi Crossing – Nasir Jump – Korangi No.21/2 – Korangi No.5. 5 7:45 a.m 4K Chowrangi – 2 Minute Chowrangi – 5C-4 (Bara Market) – Saleem Centre – U.P Mor – Nagan Chowrangi – Gulshan Chowrangi – NEDUET (Main Campus). 6 7:15 a.m Shama Shopping Centre – Shah Faisal Police Station – Bagh-e-Korangi – Singer Chowrangi – Khaddi Stop – Korangi No.5 – Korangi No.6 – Landhi No.6 – Landhi No.5 – Landhi No.4 – Landhi No.3 – Landhi No.1 – Landhi No.89 – Dawood Chowrangi – Murghi Khana – Malir No.15 – Malir Hault – Star Gate – Natha Khan – Drig Road – Nipa – NED Main Campus. 7 7:35 a.m Islam Chowk – Orangi (No.5) – Metro Cinema – Abdullah College – Ship Owner College – Qalandarya Chowk – Sakhi Hassan – Shadman No.1 – Buffer Zone – Fazal Mill – Nipa – NEDUET (Main Campus). -

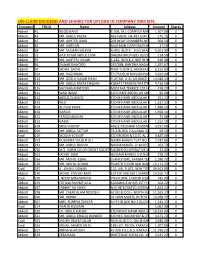

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

The State of Human Rights in Ten Asian Nations

The State of Human Rights in Ten Asian Nations - 2011 Asian Nations Ten of Human Rights in State The The State of Human Rights he State of Human Rights in Ten Asian Nations in Ten Asian Nations - 2011 T - 2011 is the Asian Human Rights Commission’s (AHRC) annual report, comprising information and analysis on the human rights violations and situations it encountered through its work in 2011. The report includes in-depth assessments of the situations in Bangladesh, Burma, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The AHRC works on individual human rights cases in each of these countries and assists victims in their attempts to seek redress through their domestic legal systems, despite the difficulties encountered in each context. Through this work, the organisation gains detailed practical knowledge of the obstacles and systemic lacuna that prevent the effective protection of rights and enable impunity for the perpetrators of violations. Based on this, the organisation then makes recommendations concerning needed reforms to the legal frameworks and state institutions in each setting. This work aims to enable the realisation of rights in a region that remains blighted by crippled institutions of the rule of law, which are enabling systemic impunity for the gamut of grave human rights violations, including torture, forced disappearances, extra-judicial killings, attacks on and discrimination against minorities, women and human rights defenders, as well as widespread violations of a range of other -

Site Name City a & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION

Site Name City A & Y Filling Station Karachi AFTAB SERVICE STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION Karachi AHMED FILLING STATION ORANGI Karachi AISHA SERVICE STATION Karachi Al - Ayaan Filling Station Karachi Al Raheem Filling Station Karachi AL-KARIM SERVICE STATION Karachi Almas Filling Station Karachi AL-RAFAY SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SAEED SERVICE STATION Karachi AL-SIDDIQUE SVC STN Karachi AMMA SERVICE STATION Karachi Arafat Filling Station Karachi ASAD PETROLEUM SERVICE Karachi Atrium Petroleum and CNG Services Karachi AWAN BALOUCH TRUCKING STATION Karachi Babar Filling Station Karachi Beachview Filling Station Karachi Bismillah Associates Karachi Burraq Filling Station Karachi CENTRAL GASOLINE Karachi Central Gasoline II Filling Station Karachi Chairman Service Station Karachi Chinar Filling Station Karachi CNG SYSTEMS Karachi Data Filling Station Karachi Enchante' Filling Station-COCO Karachi ESSA PETROLEUM Karachi Excel Petroleum Service Karachi FAISAL SERVICE STATION Karachi FARZAM FUEL STATION Karachi GOTEWALA SERVICE STATION Karachi GULSHAN SERVICE STATION Karachi HAFIZ SUDAIS FILLING STATION Karachi HIGH SPEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Hub Filling Station Karachi Jannat Filling Station Karachi JAVED SERVICE STATION Karachi Jinnah Petroleum Karachi KAMAL SERVICE STATION Karachi KARIMI AUTOS Karachi KHAWAR SHAHEED SERVICE STATION Karachi Khazan Associates Karachi KHYBER PETROL SERVICE Karachi Lavender Filling Station Karachi LUCKY SERVICE STATION Karachi M/s. Madina Filing Station Karachi Madni Filling Station Karachi MAKKAH AUTOS Karachi Malir Filling Station Karachi Mashallah Associates Karachi MILLAT SERVICE STATION Karachi Mina Filling Station Karachi MM FILLING STATION Karachi Moon Filling Station Karachi NAVEED TRUCKING Karachi New Korangi Filling Station Karachi NEW TOWN FUEL STATION Karachi NORTHERN GASOLINE Karachi QASIM SERVICE STATION Karachi RAJA 2 PETROLEUM Karachi RAJA SERVICE STATION Karachi Reda Filling Station Karachi Rehman Filling Station Karachi REX SERVICE STATION Karachi RM FILLING STATION Karachi S. -

Baloch Nationalism and the Geopolitics of Energy Resources: the Changing Context of Separatism in Pakistan

BALOCH NATIONALISM AND THE GEOPOLITICS OF ENERGY RESOURCES: THE CHANGING CONTEXT OF SEPARATISM IN PAKISTAN Robert G. Wirsing April 2008 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. This publication is a work of the U.S. Government as defined in Title 17, United States Code, Section 101. As such, it is in the public domain, and under the provisions of Title 17, United States Code, Section 105, it may not be copyrighted. ii ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, U.S. Pacific Command; Department of the Army; the Department of Defense; or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) publications are available on the SSI homepage for electronic dissemination. Hard copies of this report also may be ordered from our homepage. SSI’s homepage address is: www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil. ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please subscribe on our homepage at www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army. -

Religion and Nationalism: Contradictions of Islamic Origins and Secular Nation-Building ∗ in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan

Religion and Nationalism: Contradictions of Islamic Origins and Secular Nation-Building ∗ in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan Sener Akturk, Koc¸University Objectives. Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan have been persistently challenged, since their founding, by both Islamist and ethnic separatist movements. These challenges claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people in each country. I investigate the causes behind the concurrence of Islamist and ethnic separatist challenges to the state in Turkey, Algeria, and Pakistan. Method. This research employs comparative historical analysis, and more specifically, a most different systems design. In ad- dition to small-N cross-national comparison, I also designed an intertemporal comparison, whereby Turkish, Algerian, and Pakistani history is divided into four periods, corresponding to preindepen- dence, mobilization for independence, postindependence secular nation-building, and Islamist and ethnic separatist challenge periods. Results. Contrary to the prevailing view in the scholarship, this article formulates an alternative reinterpretation of Turkish, Algerian, and Pakistani nation-state formation. These three states were founded on the basis of an Islamic mobilization against non- Muslim opponents, but having successfully defeated these non-Muslim opponents, their political elites chose a secular and monolingual nation-state model, which they thought would maximize their national security and improve the socioeconomic status of their Muslim constituencies. The choice of a secular and monolingual nation-state model led to recurrent challenges of increasing magnitude to the state in the form of Islamist and ethnic separatist movements. The causal mech- anism outlined in this article resembles what has been metaphorically described as a “meteorite” (Pierson, 2004), where the cause is short term (secular nationalist turn after independence) but the outcome unfolds over the long term (Islamist and ethnic separatist challenges). -

Armenian Journal of Political Science

ISSN 1829 - 4286 Armenian Journal of Political Science 1 201 7 Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences Center of Pe r spective Researches and Initiatives ARJPS published in the framework of Project “Center of Perspective Researches and Initiatives ” of the Scientific State Committee (Ministry of Education and Science, RA) E DITORIAL B OARD Tigran Toro syan (Editor) Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences , Armenia Sergiu Chelak Romanian Institute of International Studies, Romania Yuri Gasparyan Armenian State Pedagogical University Jerzy Jaskiernia Jan Kochanowski University, Kiel ce, Poland Malkhaz Matsaberidze Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University , Georgia Andrey Medushevsky National Research University - Higher School of Economics, Russia Sergey Minasyan Caucasus Institute , Armenia Karlen Mirumyan Brusov State Universi ty of Languages and Social Sciences , Armenia Anna Ohanyan Stonehill College, USA Rainer Schulze University of Essex, United Kingdom Irina Semenenko Institute of World Economy and International Relations of the RAS, Russia Levon Shirinyan Armenian Sta te Pedagogical University Victor Soghomonyan Brusov State University of Languages and Social Sciences , Armenia Albert Stepanyan Yerevan State University , Armenia Petra Stykow Ludwig - Maximilians Universit ät M ü n c h en , Germany Talin Ter Minasian INALCO , France Levon Ze k i y an Venetian Institute of Oriental Studies, Italy ISSN 1829 - 4286 © Center of Pe r spective Researches and Initiatives , 201 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE AUTHORS OF ARJPS 4 NEW WORLD ORDER: REGIONAL DEVELOPMENTS Tigran Torosyan, Grigor Arshakyan Geopolitical Aspect of Russian - Turkish Relations: Rivalry or 5 Cooperation? Malkhaz Matsaberidze Peculiarities of F oreign Policy Orientation of Georgia’s Ethnic 29 Minorities POST - SOVIET TRANSFORMATIO N Anna Khvorostiankina ‘Constitutional Identity’ in the Context of Post - Soviet Transformation, Europeanization and Regional Integration Processes. -

Gulawar KHAN 2014.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Politics of nationalism, federalism, and separatism: The case of Balochistan in Pakistan Gulawar Khan Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2014. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] POLITICS OF NATIONALISM, FEDERALISM, AND SEPARATISM: THE CASE OF BALOCHISTAN IN PAKISTAN GULAWAR KHAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 Author’s declaration This thesis is carried out as per the guidelines and regulations of the University of Westminster. I hereby declare that the materials contained in this thesis have not been previously submitted for a degree in any other university, including the University of Westminster.