Fox Entertainment Group (A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD by Steve Sternberg

April 2021 #105 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD By Steve Sternberg Last year’s upfront season was different from any I’ve been involved in during my 40 years in the business. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were no live network presentations to the industry, and for the first time since I’ve been evaluating television programming, I did not watch any of the fall pilots before the shows aired. Many new and returning series experienced production delays, resulting in staggered premieres, shortened seasons, and unexpected cancellations. The big San Diego and New York comic-cons were canceled. There was virtually no pre-season buzz for new broadcast or cable series. Stuck at home with fewer new episodes of scripted series than ever to watch on ad-supported TV, people turned to streaming services in large numbers. Netflix, which had plenty of shows in the pipeline, surged in terms of both viewers and new subscribers. Disney+, boosted by season 2 of The Mandalorian and new Marvel series, WandaVision and Falcon and the Winter Soldier, was able to experience tremendous growth. A Sternberg Report Sponsored Message The Sternberg Report ©2021 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu also managed to substantially grow their subscriber bases. Warner Bros. announcing it would release all of its movies in 2021 simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max (led by Wonder Woman 1984 and Godzilla vs. Kong), helped add subscribers to that streaming platform as well – as did its successful original series, The Flight Attendant. CBS All Access, rebranded as Paramount+, also enjoyed growth. -

John Cleese & Eric Idle

JOHN CLEESE & ERIC IDLE TOGETHER AGAIN AT LAST…FOR THE VERY FIRST TIME Mesa, AZ • November 21 Tickets On-Sale Friday, June 17 at 10 a.m. June 15, 2016 (Mesa, AZ) – Still together again, Britain’s living legends of comedy, John Cleese and Eric Idle, announce their must see show John Cleese & Eric Idle: Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time in Mesa at Mesa Arts Center on November 21 at 7:30 p.m.! Tickets go on-sale to the public Friday, June 17 at 10 a.m. In Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time, Cleese and Idle will blend scripted and improvised bits with storytelling, musical numbers, exclusive footage and aquatic juggling to create a unique comedic experience with every performance. No two shows will be quite the same, thus ensuring that every audience feels like they’re seeing Together Again At Last… For The Very First Time, for the very first time. And now you know why the show is called that, don’t you? Following a successful run last fall in the Eastern US as well as a sold-out run in Australia and New Zealand this past February, their tour, John Cleese & Eric Idle: Together Again At Last…For The Very First Time will once again embark on some of the warmest (and driest) territories the US (and Canada) has to offer. The tour will take place from October 16 to November 26 and will see the British icons perform unforgettable sit-down comedy at premier venues in Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle, Spokane, Salem, Santa Rosa, San Francisco, San Jose, Thousand Oaks, Santa Barbara, Escondido, San Diego, Las Vegas, Mesa, Tucson, Albuquerque, El Paso with additional markets to be announced soon. -

LAFF Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time

LAFF Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time Week Of 10-01-2018 LAFF 10/1 Mon 10/2 Tue 10/3 Wed 10/4 Thu 10/5 Fri 10/6 Sat 10/7 Sun LAFF 06:00A Movie: Dear God Movie: Double Take Movie: Funny About Love Movie: Milk Money Movie: Superstar Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC Movie: All I Want For Christmas 06:00A 06:30A TV-PG L, V; 1996 TV-14 D, L, V; 2001 TV-14 D, S; 1990 TV-PG D, L, S, V; 1994 TV-14 D, L, V; 1999 Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC TV-PG; 1991 06:30A 07:00A CC CC CC CC CC Cybill: TV-14 D, L; CC CC 07:00A 07:30A Cybill: TV-PG D, L; CC 07:30A 08:00A Grounded For Life: TV-PG D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Movie: Dear God 08:00A 08:30A Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC TV-PG L, V; 1996 08:30A 09:00A Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L; CC CC 09:00A 09:30A Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L; CC Grounded For Life: TV-PG L, V; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, L, S; CC Grounded For Life: TV-14 D, S; CC 09:30A 10:00A Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC Spin City: TV-14 D, L; CC E/I: Jack Hanna's -

Multiple Meanings of Family Issue FF26

Multiple Meanings of F Family Focus On... Multiple Meanings of Family Issue FF26 IN FOCUS: The Family Family Definitions Continuum page F1 Policy, Gender Power, and amily Family Outcomes page F2 Definitions Continuum Discourse-Dependent Families page F4 Family Values Reconsidered page F5 by Mellisa Holtzman, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Children’s Experiences as Siblings Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana in Diverse Family Structures page F7 efining exactly what one means parenthood, gay and lesbian marriage and Family Structure from the by “the family” can be difficult. parenting, infertility technologies, and the Perspective of Children page F8 D While no single legal definition of potential outcomes of human cloning. Social Fathers page F10 the family exists, policymakers at both the Moreover, given that social and techno- Lives of Foster Parents page F11 state and federal level generally classify logical changes continue to precipitate International Adoptive individuals as family members if they are changes in the structure and meaning of Families page F12 related to each other by virtue of blood, family, understanding how individuals marriage, or adoption. Relationships that choose between definitions of Adopting Children with are not based on one or more of these the family is Developmental Disabilities page F13 criteria usually do not receive state This framework allows crucial. Yet, it Infertile Couples page F15 recognition or sanction. us to contextualize is unlikely that When is a Grandparent Not a we will come to Yet few people would argue variations in family Grandparent? page F16 understand indi- with the idea that family is definitions and understand viduals’ choices Family Identities of Gay Men page F17 based on something more than their implications. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

From Broadcast to Broadband: the Effects of Legal Digital Distribution

From Broadcast to Broadband: The Effects of Legal Digital Distribution on a TV Show’s Viewership by Steven D. Rosenberg An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2007 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Jarl G. Kallberg Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Legal Digital Distribution............................................................................................. 6 2.1 iTunes ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Streaming ................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Current thoughts ...................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Financial importance ............................................................................................. 12 3. Data Collection ............................................................................................................ 13 3.1 Ratings data ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Repeat data ............................................................................................................ -

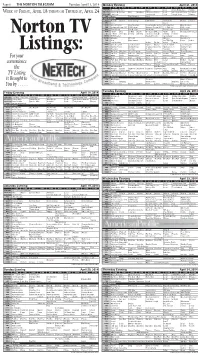

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

Dennis Chambers

IMPROVE YOUR ACCURACY AND INDEPENDENCE! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE FUSION LEGEND DENNIS CHAMBERS SHAKIRA’S BRENDAN BUCKLEY WIN A $4,900 PEARL MIMIC BLONDIE’S PRO E-KIT! CLEM BURKE + DW ALMOND SNARE & MARCH 2019 GRETSCH MICRO KIT REVIEWED NIGHT VERSES’ ARIC IMPROTA FISHBONE’S PHILIP “FISH” FISHER THE ORIGINAL. ONLY BETTER. The 5000AH4 combines an old school chain-and-sprocket drive system and vintage-style footboard with modern functionality. Sought-after DW feel, reliability and playability. The original just got better. www.dwdrums.com PEDALS AND ©2019 Drum Workshop, Inc. All Rights Reserved. HARDWARE 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 LAYER » EXPAND » ENHANCE HYBRID DRUMMING ARTISTS BILLY COBHAM BRENDAN BUCKLEY THOMAS LANG VINNIE COLAIUTA TONY ROYSTER, JR. JIM KELTNER (INDEPENDENT) (SHAKIRA, TEGAN & SARA) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (STUDIO LEGEND) CHARLIE BENANTE KEVIN HASKINS MIKE PHILLIPS SAM PRICE RICH REDMOND KAZ RODRIGUEZ (ANTHRAX) (POPTONE, BAUHAUS) (JANELLE MONÁE) (LOVELYTHEBAND) (JASON ALDEAN) (JOSH GROBAN) DIRK VERBEUREN BEN BARTER MATT JOHNSON ASHTON IRWIN CHAD WACKERMAN JIM RILEY (MEGADETH) (LORDE) (ST. VINCENT) (5 SECONDS OF SUMMER) (FRANK ZAPPA, JAMES TAYLOR) (RASCAL FLATTS) PICTURED HYBRID PRODUCTS (L TO R): SPD-30 OCTAPAD, TM-6 PRO TRIGGER MODULE, SPD::ONE KICK, SPD::ONE ELECTRO, BT-1 BAR TRIGGER PAD, RT-30HR DUAL TRIGGER, RT-30H SINGLE TRIGGER (X3), RT-30K KICK TRIGGER, KT-10 KICK PEDAL TRIGGER, PDX-8 TRIGGER PAD (X2), SPD-SX-SE SAMPLING PAD Visit Roland.com for more info about Hybrid Drumming. Less is More Built for the gigging drummer, the sturdy aluminum construction is up to 34% lighter than conventional hardware packs. -

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports Can Play in ESPN's Arena

Challenging ESPN: How Fox Sports can play in ESPN’s Arena Kristopher M. Gundersen May 1, 2014 Professor Richard Linowes – Kogod School of Business University Honors Spring 2014 Gundersen 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship ESPN has with the sports broadcasting industry. The study focuses on future prospects for the industry in relation to ESPN and its most prominent rival Fox Sports. It introduces significant players in the market aside from ESPN and Fox Sports and goes on to analyze the current industry conditions in the United States and abroad. To explore the future conditions for the market, the main method used was a SWOT analysis juxtaposing ESPN and Fox Sports. Ultimately, the study found that ESPN is primed to maintain its monopoly on the market for many years to come but Fox Sports is positioned well to compete with the industry behemoth down the road. In order to position itself alongside ESPN as a sports broadcasting power, Fox Sports needs to adjust its time horizon, improve its bids for broadcast rights, focus on the personalities of its shows, and partner with current popular athletes. Additionally, because Fox Sports has such a strong regional persona and presence outside of sports, it should leverage the relationship it has with those viewers to power its national network. Gundersen 2 Introduction The world of sports is a fast-paced and exciting one that attracts fanatics from all over. They are attracted to specific sports as a whole, teams within a sport, and traditions that go along with each sport. -

Spring 2003 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 P.M

Spring 2003 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 p.m. - 11 p.m. February 22 - March 15, 2003 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 7 Air Farce On the Road Again Mr. Bean Life & Times Movie It’s a Living 22 Minutes Mr. Bean Opening Night 8 22 Minutes Air Farce NHL Hockey Last Chapter Wind at My Back Marketplace Red Green Anne Murray 9 American in Canada Disclosure Fifth Estate Witness Nature of Things Made in Canada After Hours 10 Sunday Report The National At the End CBUT Venture 7 Entertainment Tonight Body & Health The Simpsons Bob & Margaret Reba Bob & Margaret Friends Blackfly State of the Heart King of the Hill 8 70s Show The Simpsons Boston Public Let's Make a Deal Survivor Dawson's Creek PSI Factor Popstars Greek Life 9 Frasier Will & Grace Malcolm Married by America Married by America Hack Mutant X A.U.S.A Popstars Raymond 10 Crossing Jordan Judging Amy Gilmore Girls Without a Trace Blue Murder Andromeda Dragnet CHAN 7 Blind Date Fashion TV Speakers Corner Fifth Wheel StarTV DiverseCITY 8 CHUM The Immortal Smallville Enterprise Joe Millionare Lexx First Wave Dead Man's Gun 9 Joe Millionaire Movie I'm A Celebrity Are You Hot? Movie Movie Movie 10 Blind Date Movie Movie All American Girl Lexx CKVU Fifth Wheel 7 Friends Oliver Beene Mysterious Ways Access Hollywood Degrassi 8 8 Simple Rules My Wife & Kids Just for Laughs American Idol Fastlane Law & Order Alias According to Jim American Idol Scrubs 9 Third Watch CSIWest Wing CSI W-Five Figure Skating Law & Order 10 CSI Miami The SopranosLaw & Order ER Law & Order